This weekend, thousands of runners will dash all around the city during the annual BMW Dallas Marathon.

Since the early 1970s, runners from far and wide have jogged and sprinted around Dallas in the annual 26.2-mile race. The marathon has evolved since its initial run in 1971, including pushing the race from March to December, moving the start and finish lines to City Hall, and adding other events, like the half-marathon and Mayor’s Race 5K. What began as a small event with 82 runners 52 years ago grew to more than 14,000 runners in 2022.

With everything going on this weekend, the logistics are bound to trip you up—even if you don’t plan on running. Here’s everything you need to know about navigating the Dallas Marathon Friday through Sunday’s race day. Especially if you need to get around East Dallas and downtown.

Audio and video calls continued, but with more diverse background noise or view, my mute listening skills increased, and, over time, I shrank. As any cyclist will, I fell a time or two, on crushed limestone and hopping a rushing grate. I learned to see things better, smell a little keener, and I stopped falling.

Audio and video calls continued, but with more diverse background noise or view, my mute listening skills increased, and, over time, I shrank. As any cyclist will, I fell a time or two, on crushed limestone and hopping a rushing grate. I learned to see things better, smell a little keener, and I stopped falling. Knotted up in a Cowtown mediation once, the mediator proposed the lawyers hit one golf ball each over their Trinity to break the impasse. It is a very easy half-wedge, if you care to know. But let’s be honest: in the Trinity’s 700-mile traverse from near the Red River to Galveston Bay, there may not be a less attractive stretch than the straight line of its diverted, fabricated run through Dallas. For years, I’ve run on and inside the levees, and the only thing I don’t look at is the lonely, silty river, flanked by weeds and detritus.

Knotted up in a Cowtown mediation once, the mediator proposed the lawyers hit one golf ball each over their Trinity to break the impasse. It is a very easy half-wedge, if you care to know. But let’s be honest: in the Trinity’s 700-mile traverse from near the Red River to Galveston Bay, there may not be a less attractive stretch than the straight line of its diverted, fabricated run through Dallas. For years, I’ve run on and inside the levees, and the only thing I don’t look at is the lonely, silty river, flanked by weeds and detritus. “You got disc brakes on your bicycle?”

“You got disc brakes on your bicycle?”

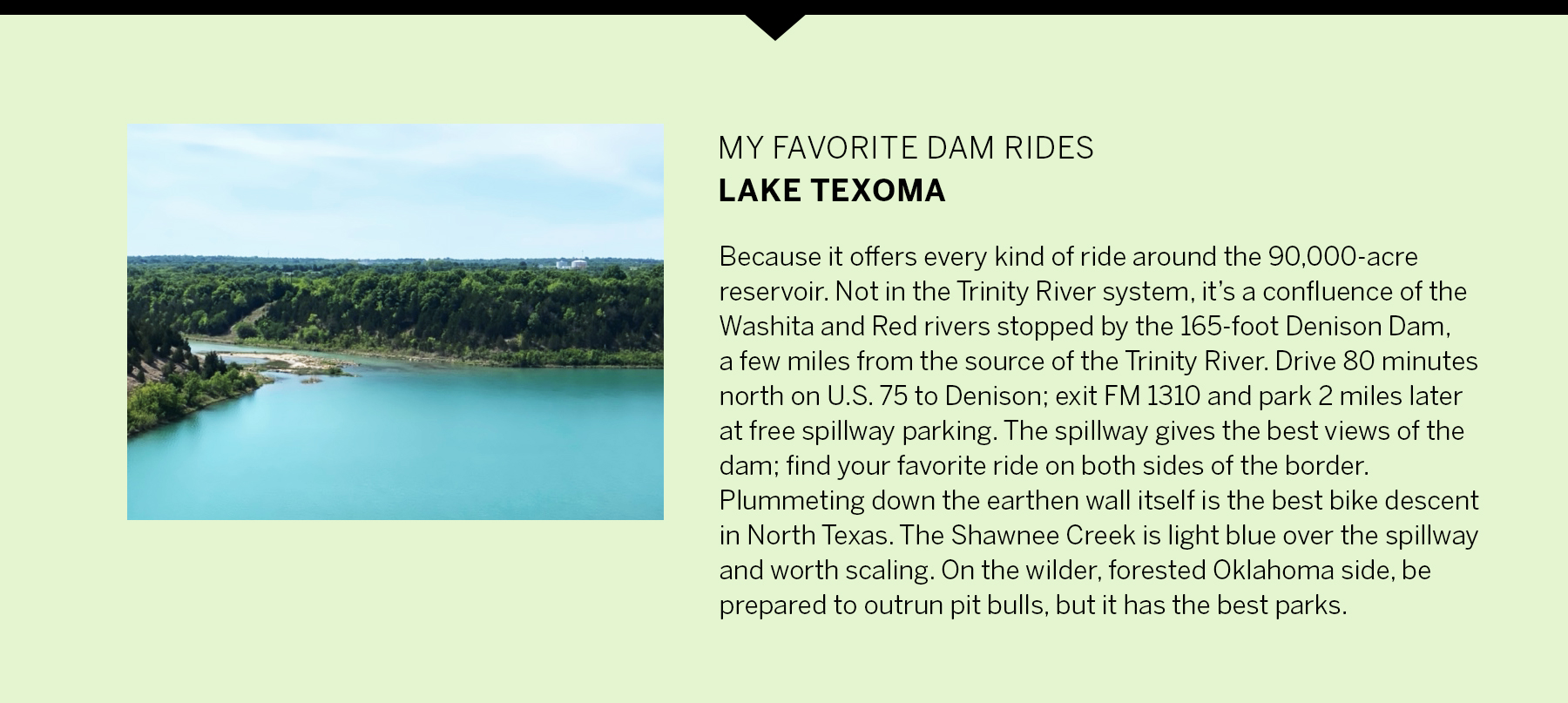

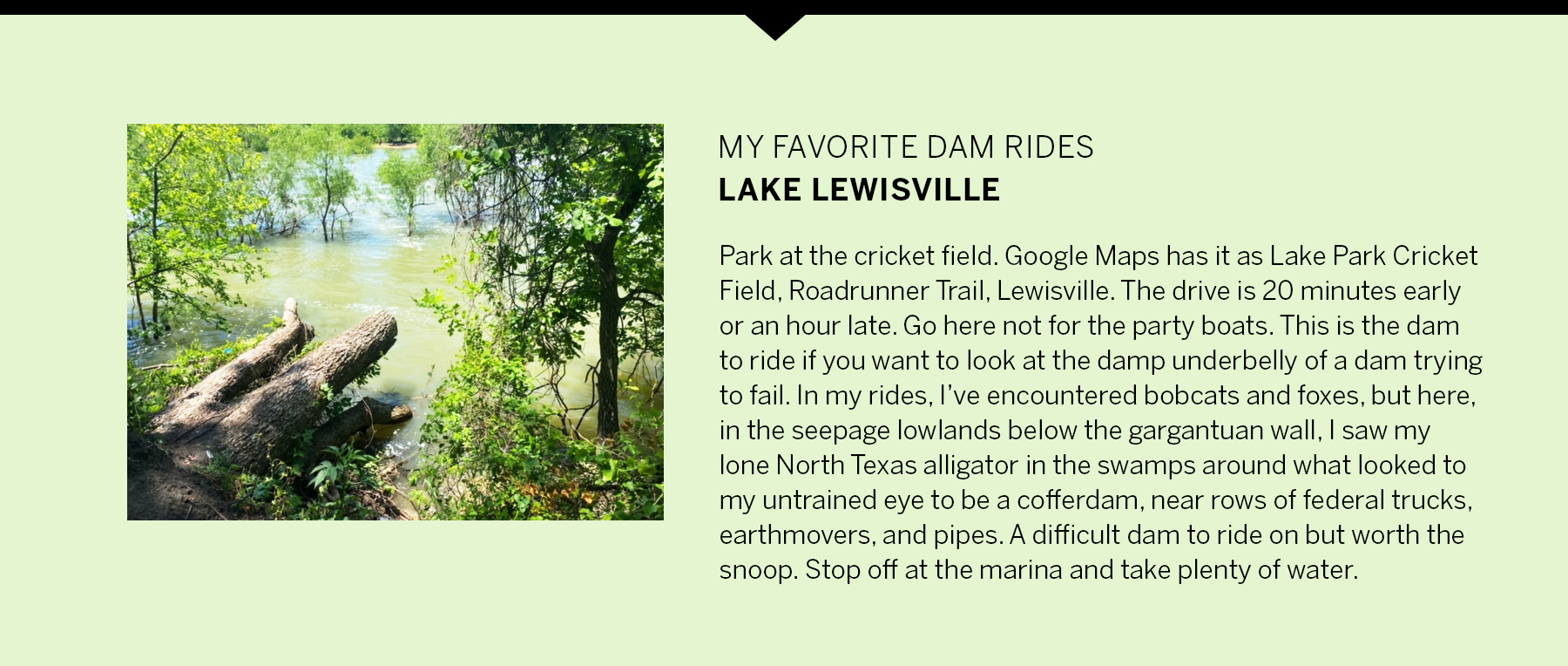

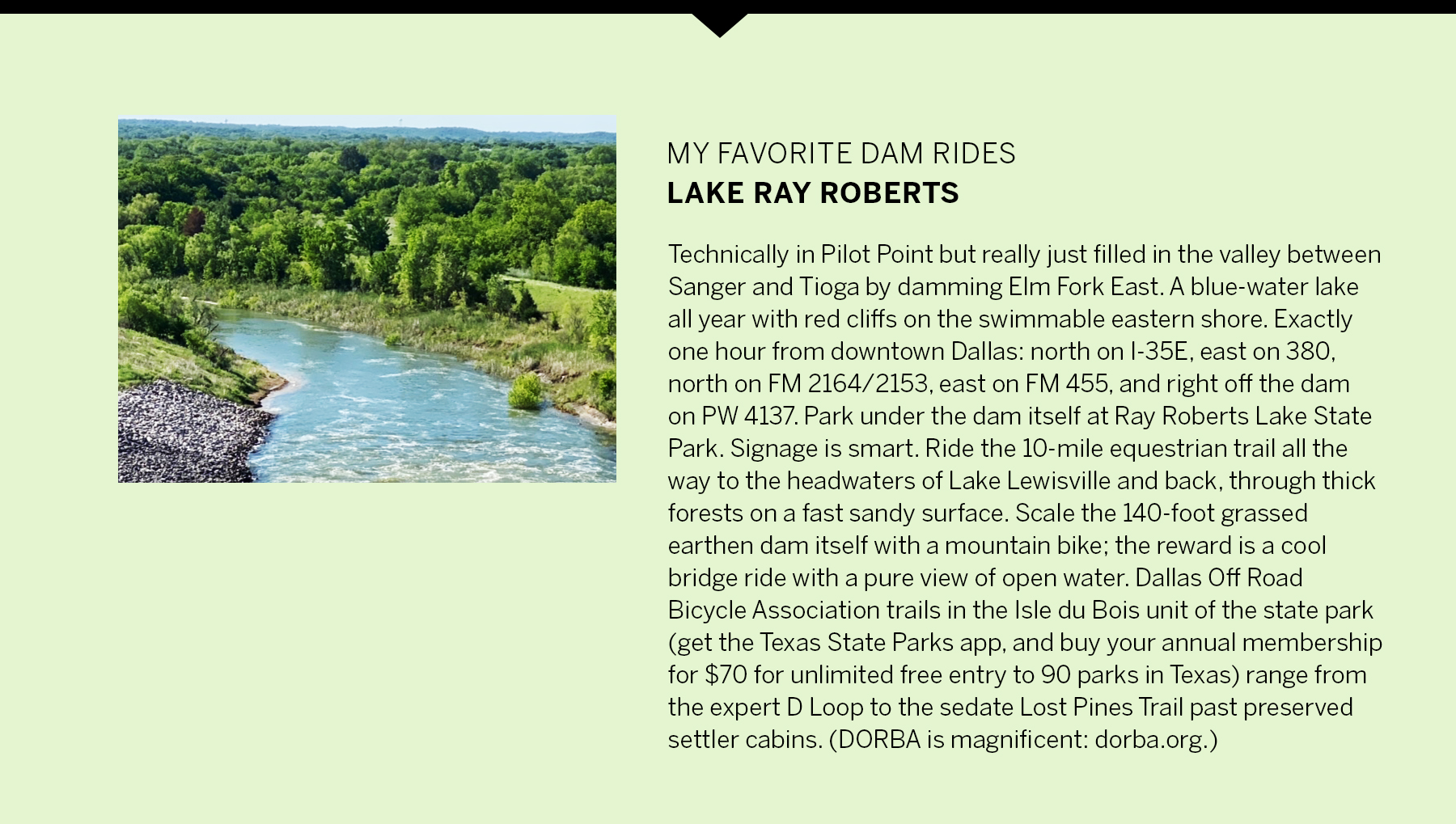

For a year or more, I have explored this trickling, flooding, ambivalent watershed, and if we decide we want to add cafes and performance spaces, I will enjoy the spectacle, but I will carry in my mind the dammed reservoirs upstream and wonder about the scale of what we can do, and ought to do.

For a year or more, I have explored this trickling, flooding, ambivalent watershed, and if we decide we want to add cafes and performance spaces, I will enjoy the spectacle, but I will carry in my mind the dammed reservoirs upstream and wonder about the scale of what we can do, and ought to do.