D Magazine’s 50 Greatest Stories: Cullen Davis Finds God as the ‘Evangelical New Right’ Rises

In 1980, Cullen Davis, the richest person to ever be tried for murder, was back in his Fort Worth mansion after two years in prison. His highly publicized trial, in which he was charged with killing his 12-year-old stepdaughter during a home invasion, had ended with a verdict of not guilty following the wizardry of famed attorney Richard “Racehorse” Haynes, whose cross examination of Davis’ ex-wife, Priscilla, was so stirring that legal observers knew a conviction wouldn’t happen even though another 10 weeks of testimony remained.

Two years prior brought an allegation that Davis attempted to hire a hitman to kill the judge presiding over his divorce. He was facing a wrongful death lawsuit from Priscilla, who had been wounded in the shooting, and prosecutors hadn’t tried him for the murder of his ex-wife’s new partner, Stan Farr.

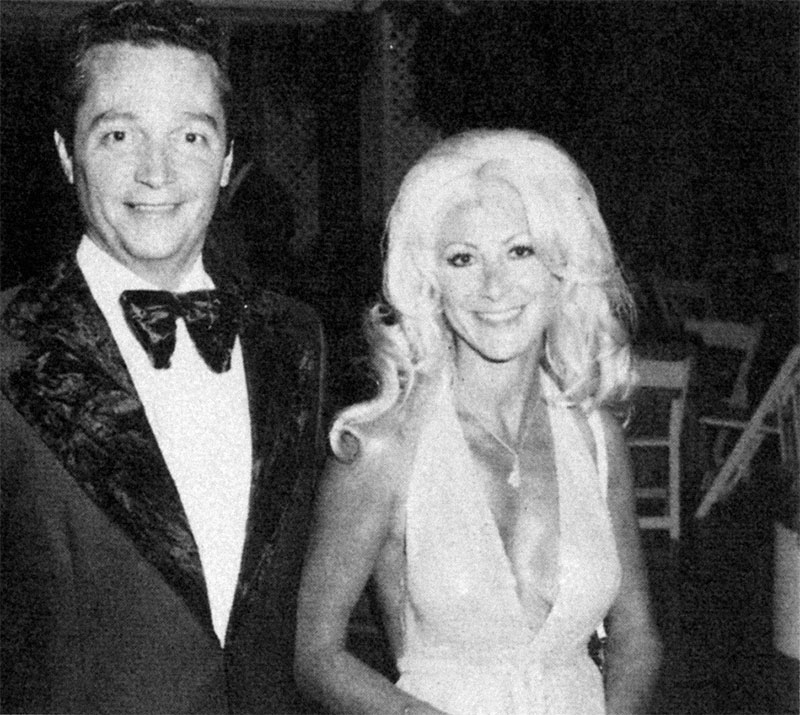

That’s a lot to process. And so when he and his third wife, Karen, walked to the front of First Baptist Church of Euless to formally accept Jesus Christ as their lord and savior, it was not a surprise to everyone. The longtime legal reporter Allen Pusey in 1980 got curious about this new chapter of his life, how a man who famously once screened Deep Throat during the Colonial Invitational Golf Tournament and was known for lavish parties and late nights decided to lay down his life for God.

His story, “The Conversion of Cullen,” is one of our 50 greatest, a companion piece of sorts to Tom Stephenson’s 1977 chronicle of the murders, “Is Priscilla Davis’ Story True?” The conversion was the work of the evangelical televangelist James Robison, an imposing 37-year-old preacher who had ambitions of his own Billy Graham-style enterprise. His rhetoric from nearly half a century ago may have been novel then, but is now part of our body politic: government has overstepped and forgotten God, creating space for “the radicals, the communists, the feminists, the gays,” as he once said.

In Cullen, he saw opportunity. “God has a task for you,” he once told his wealthy parishioner. “I think you could be extremely helpful in His work.” (Here’s where Cullen is today.)

Pusey doesn’t suggest that Cullen’s conversion was false, but he lays out how it happened and what happened after it did. Robison was certainly onto something. In 1981, Texas Monthly profiled the preacher it called “God’s Angry Man.”

Johnny Cash calls him a man of destiny. W. A. Criswell, pastor of the First Baptist Church in Dallas, describes him as “a new star in the galaxy of God’s flaming, shining lights who point men to Christ.” Jerry Falwell proclaims him to be “the prophet of God for this day.” And the late H. L. Hunt called him “the most effective communicator I have ever heard.”

Almost twenty years ago James Robison set himself a course that many felt would eventually enable him to fill the gap left in the hearts, minds, and stadiums of America when Billy Graham passed from the scene. His blunt, sometimes crude forthrightness probably makes that expectation unrealistic, but this same quality has helped propel him to a position of public leadership second only to Falwell’s in what has come to be called the Evangelical New Right.

Pusey’s piece follows Cullen and establishes the foundation for this movement. It’s one of the greatest stories we’ve ever published, and you can read it here.