Editor’s Note: This story was first published in a different era. It may contain words or themes that today we find objectionable. We nonetheless have preserved the story in our archive, without editing, to offer a clear look at this magazine’s contribution to the historical record.

It was a day to chase the ghosts from the house on Hulen Street. A gentle June breeze blew lightly through the shade, undulating the chest-high Johnson grass in the fields behind the mansion. A summer sun browned the vast front lawn, soaked the tiled terrace, and warmed the white stucco walls that erupt trapezoidal from the crest of the hill.

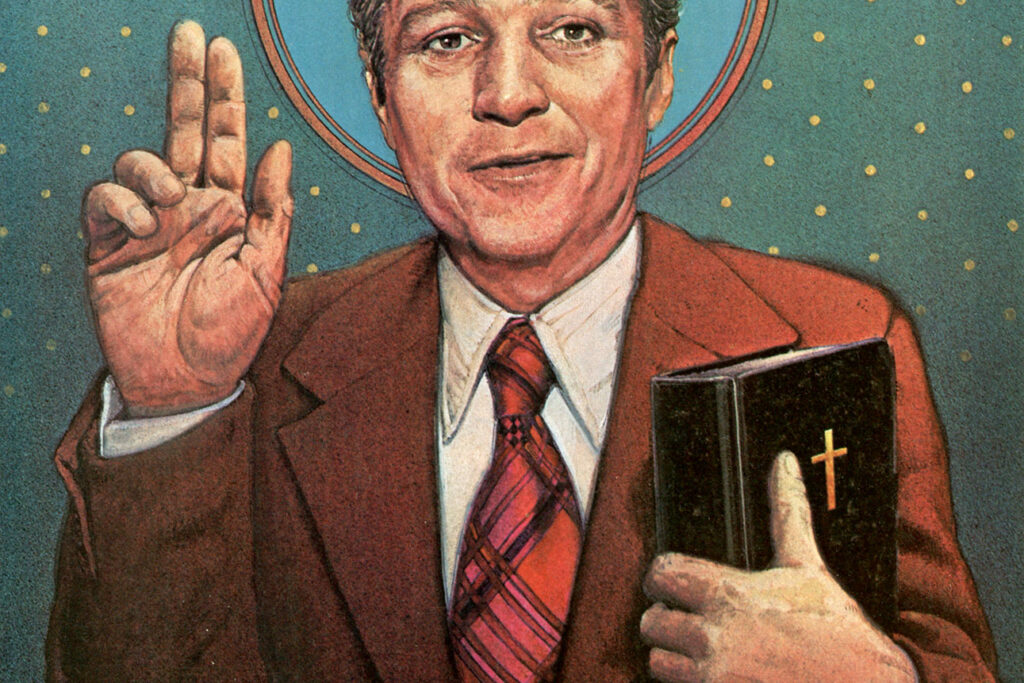

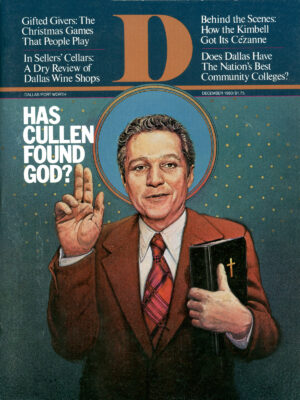

It was here — a few footsteps from the basement where 12-year-old Andrea Wilborn was murdered, just down the slope from the kitchen where Stan Farr’s body was dragged — on a makeshift podium wedged between a pair of Altec Lansing speakers that the truth was made known: The prodigal son of Stinky Davis had found the Son of God.

To the 181-acre mansion of the wealthiest man ever tried for murder, Cullen’s newfound mentor, television evangelist James Robison, had brought his tentless revival. And nearly 1,000 Davis employees and their families gathered as leisurely spectators on this back burner of Sodom for a curious melding of Mammon and the Lord.

The menfolk were spreading the blankets and unfolding the lawn chairs, and some of the women headed toward the mansion, cupping their hands to the windows to stare into the sea of designer pastels, to look at the parquet floors, the porcelain statues, the remote conversation pit, and the two young Davis boys, on loan from their mother, inside the adjacent game room with their friends shooting pool. Down the hill, lines of teenagers were forming at the cold drink stands flanking the podium. Small children raced up the walkways to tumble down the hill.

Onstage, John McKay was being thoughtful. A mile or so in the distance, he could see Amon Carter Stadium, where he once played football for TCU. These days, McKay sings at Robison revivals, specializing in latter-day hymns fashioned from old Elvis Presley songs. Like most others, McKay marveled at the divine intervention he deemed responsible for bringing the troubled cosmos of Cullen Davis under the flag of the Robison Crusade.

“Of the 10 places I never expected to be, this has to rank near the top,” he was saying. “It has to be the work of the Lord.”

The legacy of the mansion, however, was no work of the Lord. It was the murderous handiwork of a mysterious man in black.

On a muggy night in August 1976, an unknown intruder disconnected the burglar alarm, then padded through the long, hardwood hallways, killing as he went. In the basement, he shot Andrea, Cullen’s stepdaughter, in the chest. She died with her eyes open, her body face up. Stan Farr, Cullen’s estranged wife’s lover, was shot four times and his body dragged down the hallway to a kitchen door. Cullen’s wife, Priscilla, was greeted with a gunshot to the chest. Her friend, Gus Gavrel, was wounded and lay paralyzed on the floor.

Priscilla believed her assailant was Cullen. The government believed it was Cullen. But after nearly two years behind jail bars, a hung jury, two acquittals, a cottage industry of gossip about all night parties, jet set carousing, and videotaped sex, the story comes down to Cullen and the preacher, a beautiful June Saturday, and the hand of the Lord.

Up on the veranda, Davis seemed pained. While Robison was pressing flesh like a ward heeler at a Labor Day picnic, Cullen fingered the change in his pockets, eyeing nervously the incoming crowd. Dressed casually, in cheap blue trousers and a Mexican guyavera, Cullen was anything but relaxed. Two years in jail has not tempered his unease with strange people. Four years in the spotlight has not made him at ease with the press. If the Lord has changed Cullen’s heart, He’s left everything else the same.

The eyes are still deep and glassy-dark, mirrored surfaces that shift frantically when curious. When they turn cold, they sink like stones. His patience seems only loosely bridled, his constant fidgeting suggesting a turbulence underneath. Often his sentences seem fragmented by frustration, as though speaking is an unaccustomed facility, despite his four-year engagement with the press.

When he took his turn at the podium, his panic had not died. His greeting was a salvo of mixed signals, mock humor ringing with discomfort.

“I was asked if my life had changed,” said Davis, an uncertain witness. “My answer to that is that you wouldn’t be here if I hadn’t.”

The crowd laughed at the irony, but the laughter was hollow. There was a sharp edge buried there somewhere. They seemed to feel it at once.

Back at the house, Karen Davis popped in and out serving cold drinks and embracing old friends. She was wearing a scarlet blouse over blue jeans, and three artificial red roses were pinned in her hair. Three elderly black women from Strangers Rest Baptist Church wandered into the house through an open back porch door. Karen guided them back out again with a firm but gentle tug.

By now, Robison was preaching blood and brimstone. He held fire in his eyes and mockery in his voice. But he was preaching not of Christian salvation, but of the political salvation of the nation. His syntax was that of hell and damnation. But his text was that of the Republican Party platform. He was trying to mold these minions of Mid-Continent Supply Company into soldiers for God.

He assaulted the federal government in general, the bureaucracy in particular. He assailed the SALT treaties, military cutbacks, and the windfall profits tax.

“The government is becoming a substitute for God,” sputtered Robison. “The bureaucracy is choking the life out of us.”

“Who do you think drove the spikes through those quivering hands? The government,” Robison wailed. He had hit the groove. He savaged the American lifestyle, the White House Conference on Families, the corruption and lawlessness of public officials, and the decision to take money off the gold standard.

“Don’t ask the Supreme Court what a law is,” Robison said. “They make it up as they go along.”

“The church of the Lord Jesus Christ is not a fortress, it’s an army. Get committed. The radicals, the communists, the feminists, the gays — they’re organized. They’re committed.”

By the time Cullen Davis made it back to the podium, the cameras were cranking. Still photographers were snapping. Cullen Davis was still news.

When the meeting broke, part of the crowd broke for the podium. They stood in line to shake Cullen’s hand. Each grabbed him by the shoulder and told him how he had been saying something that needed to be said.

But others in the crowd wandered back toward the mansion, and again began cupping their hands to windows as they bent over the shrubs. Again, they were ooooohing at the porcelain, aaaaahing at the fireplace, and pointing to the hallway where Stan Farr died.

• • •

Five weeks before, Cullen and his third wife, Karen Master Davis, strode down the burnt orange carpeting of the First Baptist Church of Euless to declare their service to Jesus by a profession of faith. They stood quietly in front of the congregation at the tail end of the service, stunning Rick Braswell, the stand-in preacher, and sending a titillating throb through the heart of Fort Worth.

After the service, Braswell called the church’s pastor, the Rev. Jimmy Draper. Draper is a conservative Baptist, a fundamental Christian who believes in the Bible as literal law.

“Guess who stepped forward today?” said Braswell.

“Who?” asked Draper.

“Mr. and Mrs. Cullen Davis,” said Braswell.

“I’ll be darned,” Draper said.

Draper was not totally surprised. James Robison is a member of the First Baptist Church of Euless. He recalled that one Sunday 18 months ago, he had asked Robison to give the sermon on a day he had felt unmoved. From nowhere and apropos of nothing, Robison asked the group to pray for Cullen Davis. Cullen was once again in trouble, languishing in jail. Draper knew that Robison has a taste for controversy and celebrity. He watched as Robison continued his quest for Cullen’s heart. And when the Davises stepped forward that Sunday, Robison was there at their side.

Robison had been introduced to Cullen Davis by former Mayor Pro Tem Jim Bradshaw. Bradshaw and Davis had become strange acquaintances, almost captive friends, since the night before Cullen was arrested for hiring David McCrory to murder Judge Joe Eidson. Jim and Ouida Bradshaw had been with Cullen and Karen to a Dallas Cowboys football game the very night McCrory claims he was to have had the judge killed. Later they went to the Cowboy Club with Cullen’s party. They planned to go to Acapulco. The next day Cullen was arrested with a pistol, a silencer, and $25,000 cash. Bradshaw, feeling used, had told the story to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. But that is over now, Bradshaw says.

“I had gone to Jacksonville, Florida, for a Bible conference with James,” said Bradshaw. “Jimmy Draper was there, too. James had been trying to get me to introduce him to Cullen Davis, and over dinner he asked again. I told him I would.”

A few weeks later, the three met in Cullen’s office at Mid-Continent Supply. Robison told him about his crusade. About his plans for the Religion Roundtable, a fundamentalist organization that would become heavily involved in local and national politics. Robison talked earnestly for nearly an hour. Davis says he was overwhelmed by Robison’s tough personality. He liked his politics and he liked the sound of the organization. But toward the end of the conversation, as Davis recalls it, Robison said he wanted more. Robison squared his jaw, shifted his massive form forward, and glared at Davis with his fiery dark eyes.

“I think God has a task for you,” whispered Robison. “I think you could be extremely helpful in His work.

Robison is an impressive man. He is tall, dark, and muscularly built. His eyes are intense orbs; his mind is quick, and his tongue is sharp.

He was, as he pridefully points out, an almost-aborted baby, born unwanted to a 41-year-old mother in Houston 37 years ago. He hunted big game until his followers began complaining. He still owns a deer lease and keeps animal heads on his walls.

On a makeshift podium wedged between two speakers, the truth was made known: The prodigal son of Stinky Davis had found the Son of God.

Robison runs a $14-million electronic evangelical association, small next to a Pat Robertson or a Jerry Falwell. But what he lacks in fiscal strength, he makes up in hustle. He is tough enough in his own right, but he is quick to spot a headline. When WFAA-TV tried to keep him off the air after several allegedly derogatory statements about homosexuals, Robison parlayed his troubles into a pointed crusade. When Anita Bryant announced a break with her husband, Robison headed for Florida to help her out. When Jerry Falwell formed his Moral Majority, Robison countered with the Religion Roundtable, culminating with the National Affairs Briefing here in Dallas which attracted the luminaries of the conservative world.

Robison makes a $50,000 salary from his 90-station network and a 400,000-name mailing list. In recent years Robison has polished his style, shored his financial backing, and joined the race among electronic evangelists to become the new Billy Graham.

It was his drive that Davis says he was attracted to. Perhaps he recognized in Robison something of himself.

Davis mulled over Robison’s message and a few weeks later invited Robison and his wife to the mansion for dinner. It was April 9, and before the evening was over, Robison had Cullen and Karen on their knees in the study, dedicating their souls to Jesus and their energies and money to the Robison Crusade. For Karen, it was the end of a subtle campaign to domesticate Cullen. After the trial and the spotlight and the uncertain future, he had remained a loner. She and her two boys went to church. Cullen stayed at home. Sundays were for football, a little beer, a little pool. For Cullen, however, that moment of experience was plain peculiar, nothing overwhelming; as though he were doing a chore he had avoided for some time. There were no lights, no rolling drums, no gentle flames from votive candles. Only the tugging he says he felt in jail.

“I used to think when I was in jail what God would have me do if I asked Him. But I never did,” says Davis.

“I guess it just comes to some people differently. I used to see those people on television, big strong men, who would fall all over the floor and cry. I used to think how embarrassing it would be if that would happen to me.”

Davis gave his life to God once before. He recalls that he very quickly took it back.

“I was 16, and I went to a Billy Graham crusade. When they asked people to come down and dedicate their lives to Jesus, I did. But when I went home, I guess I just went right on sinning just like nothing happened.”

In jail, said Davis, he received 15 letters a day from people who claimed to be praying for him, praying that God would forgive him or save his mortal soul.

“I figured if that many people prayed for me and took the time to write, there must be thousands of people out there who prayed, but wrote nothing at all. I honestly think now that it was those prayers that had more to do with my acquittal than any one thing,” Davis said.

He and Karen speak now at churches in Fort Worth and Dallas. Cullen stands in for Robison on occasions when Robison finds he can’t be there. He is exploring the evils of secular humanism and is reviewing in horror the sort of sex education taught in the Dallas public schools. He has come a long way from the days when he gave private showings of Deep Throat at the Colonial invitational Golf Tournament.

There are those who are not impressed by the conversion of Cullen Davis. Many who don’t believe it think he is posturing for the sake of his upcoming trials. Priscilla Davis has an injury and wrongful death suit lodged against him. Gus Gavrel has an injury suit of his own. Cullen’s first wife Sandra recently sued to have her support payments for their two sons raised; they were raised to $3,000 per month. Although he has weathered, certainly, the worst of his difficulty, prosecutor Jack Strickland believes that every little bit helps. Strickland prosecuted Cullen in his most recent trial, the murder-for-hire retrial in Fort Worth.

“I think his association with Robison can’t do anything but help,” said Strickland. “We’ve found juries very much influenced by what happens outside the courtroom. During the Fort Worth trial, Cullen used to eat in the Tandy Cafeteria. We found out later that the jury was very much influenced by that. They were thinking: Gee, this is just a regular guy, eating with us even though he’s a millionaire. I wonder how many times he’s eaten there since. I’ll bet he hasn’t made it out of the Petroleum Club.”

Needless to say, Strickland believes that Cullen Davis murdered Andrea Wilborn that night in the mansion. He believes Davis hired David McCrory to kill Judge Eidson. And he believes money, not divine intervention, allowed Cullen Davis to go free.

“I hear he was going to become a Catholic until he found out that Catholics require a confession,” joked Strickland. “I hope he doesn’t give God a bad name.”

Strickland is not the only one a bit suspicious about Cullen and Robison. Kay Davis, Cullen’s niece, works at Mid-Continent with Cullen. She has no real doubt that something has happened to Cullen, but she also has no doubt that Cullen is being used. Although she has never considered the possibility that Cullen murdered anybody, she considered him a bit foolish and self-indulgent.

“Karen felt, and has always considered, Cullen’s public image as very important. I’m sure she thought that his turning to religion, or appearing to turn to religion, or even the suggestion that he would turn to religion would help his public image,” Kay said.

“But Cullen has a cause now, where he never had one before. Cullen has spent more time fulfilling his obligations with Robison than he has with anything else in years. He’s been promoting James among his friends. He distributes James’ book among his workers, and he’s never done anything like that before. I think he’s had more Bible study sessions at his house than he has company parties. I guess we’re lucky he didn’t go on a diet.

“All that is nice, but where was Robison four years ago? Cullen really needed him then, when he was in jail, not now that he is back in the mansion.

“But what bothers me is that no matter how you figure it, all this is happening because Cullen is a celebrity. He’s a famous person. And he’s famous because he was once accused of killing a 12-year-old girl,” Kay said. “All those people he’s speaking to — those are James’ people. They know what he’s going to say. They’ve heard it all before. The reason they go to hear him is because of who he is; because of who’s saying it, not what’s being said. They don’t want to hear what he really knows about — how to take over a company, how to start up a company, or corporate finances. They could care less. Maybe he didn’t have an opinion before on these things — on religion and morality — but if he doesn’t want the attention, he can choose to turn it off.”

• • •

Cullen was talking about religion in his study. It was Karen’s birthday, and she was celebrating in the next room with Betty Robison and the Monday morning Bible study class. He was talking about a trip to San Francisco with Karen and their visit to a Unitarian Church.

“We wanted to see what Walter Mondale was,” Cullen explained. “He’s a Unitarian.”

“They never prayed. They didn’t mention Jesus Christ one single time during their services, and they only mentioned God in some vague sense. You know, nobody in the church had a Bible. The sermon consisted of some so-called beautiful prose on self-centeredness.”

“You know, Mondale’s father was a Unitarian minister, and his brother, Lester Mondale, was one of the original signers of the Humanist Manifesto.”

He was elaborating on the “humanist conspiracy” and what has happened to America.

“You know what ‘humanism’ is?” Cullen asked, looking for some hint of recognition in my eyes. “It’s Marxism, socialism, and immorality.”

Each word rolled off his tongue as though he were removing dirt. Each time he would mention a phrase it seemed to lead back to newfound catechism of the Right.

“What’s causing more crime? What’s causing more immorality? The kids didn’t think it up. It’s humanism.”

Cullen has come a long way from the days when he gave private showings of “Deep Throat” at the Colonial Invitational Golf Tournament.

Cullen described how he is in the process of unlearning the theory of evolution. He pops quickly from Xeroxed religious tracts to tiny 40-page booklets when he is making a point. On the end table is a Bible as big as the Manhattan white pages. He talks about “change agents” paid for by the federal government to bend minds in innocent-looking federal programs. He reviews a sex manual for teenagers by a well-known psychologist. “She is descended from a tadpole,” he says with a smile. There seems little point in not believing that he really did read the Bible cover to cover in three months.

The Rev. Jimmy Draper says Davis has missed church only six Sundays since the first week in May — four while he was out of the state, one while with Bunker Hunt and the Campus Crusade in Houston, and another while attending an alumni weekend at Texas A&M.

At the First Baptist Church of Euless, the chrome has worn off the celebrity conversion, and, except for the occasional request for an autograph, Davis seems to attract little attention these days.

“He comes here and sits just like any other person,” said Draper. “He seems to give more than his share of energy to the church. He’s always bringing his friends and business contacts over here. Recently, he brought a Jewish man and his wife. He even brought a local car dealer, but I don’t think the car dealer ever came back.”

Draper has no doubts about Cullen Davis’ sincerity. But when he is asked whether his friend James Robison is using Cullen Davis, his face breaks into a gentle smile.

“I think ‘use’ may not be the right word,” said Draper. “But James has always found a need to publicize the results of his work. I have a deal with James. I don’t tell him how to run his (evangelical) association, and he doesn’t tell me how to run my church.”

Cullen himself makes no bones about his admiration for Robison. He likes him personally, likes his politics, likes his style. So he marches from church to church, from meeting to meeting, helping Robison raise money and spread his word. Racehorse Haynes tells friends that Cullen asked him to donate $25,000 for the Robison Crusade. “You’ve got it all turned around, Cullen,” Haynes said. “You’re supposed to give the lawyers money. Remember?”

• • •

There is something dreadfully ordinary about this chapter of the Cullen Davis saga. What should be an intriguing denouement to the tale of the rich man accused of murder ends in a study with the theory of evolution being unlearned. Two dead bodies, two live victims are swallowed in memory; the murder mansion becomes the castle of cliche. What seemed so full of passion in the telling is rendered colorless in the flesh. There is no suffering, no forgiveness, and no answer.

The theories that abound concerning the conversion of Cullen Davis amount to permutations of questions concerning his sincerity and his guilt. Is it real because he was guilty; is it unreal because he was guilty? He was persecuted, now he is saved? The questions provide the sort of open ending that allows us to color the pictures, rearrange the scenery, flesh out the script. It is simply another of the dead ends of logic that leads us back to where we want to be.

Cullen still has troubles. The suits by Gavrel and Priscilla hold hidden dangers. Davis has never been tried for the murder of Stan Farr, and should some new evidence be produced in the upcoming legal proceedings, there is no statute of limitations and no question of double jeopardy to protect him. A staunch religious home life could work wonders with a jury. But still, the worst must surely be behind him. He knows the routine. He knows the process. And he still has Racehorse Haynes. So why go to the trouble of reforming his lifestyle for the sake of his case? And why, if he felt it would be effective, did it not happen before?

For those who believe he was persecuted, his salvation is justified. He is, in their minds, a victim of injustice come to God’s mercy, a latter-day Job whose anguish is done. But at no time does Davis talk about that suffering, how he felt or what he learned. He dismisses his two years in jail as easily as his whereabouts August 2, 1976 — as though he doesn’t understand the question, or wants us to have no clues. If it wasn’t an important spiritual experience to him, then there is no reason it should be to us. We are visitors in the mansion. He is the keeper of the keys.

But those most devoutly convinced of his transgressions believe that the conversion is a catharsis born of conscience. They believe — because they want to — that the hands that clutch the Bible are still stained by powder burns and blood. They believe — because they want to — that Cullen Davis is haunted, shadowed as he sleeps, by a basketball player and a 12-year-old girl. Maybe, they say, he really feels guilty. Maybe. Maybe not.

Maybe he wants to cry, like those others, he remembers from television. Maybe he wants to join those souls ripped asunder by the Spirit, crippled in their joyfulness, frothing on their knees. Maybe he feels nothing. Maybe he has no conscience. Maybe, God help us, he is truly innocent and we mock him and scorn him and do him wrong. But let’s let Cullen tell it.

“I’m in good shape,” declares Davis. “No legal problems to speak of. I’m not falling down drunk. I’m not on dope. I have no insurmountable problems, and I have money. Many people who find God have one or more of these problems. So what would it benefit me to accept the Lord in my life?” Cullen says.

But there is another possibility. Perhaps the answer lies not with the ghosts of the mansion, but in the cupped hands that search for them in the halls. Perhaps after four years of jails, courtrooms, klieg lights, legal expenses, and death threats, Cullen Davis needs the attention. This might explain why he allows his “personal commitment” to be so thoroughly exploited, why he is suddenly interested in politics, or why he appears on the Charlie Rose show.

When he goes to a football game, people stand in line to chat with him. At the Colonial Country Club, giggling matrons ask him to sign their copies of Blood Will Tell. Waiters recognize him. Strangers stare at him. And vague acquaintances buy him drinks. It is no secret that Cullen Davis is Fort Worth’s top-ranked celebrity, and it may be that he has succumbed to his fame.

Perhaps, because everyone seems so willing to listen, Davis thinks he has something to say. Perhaps, because everyone seems so anxious to touch him, to flatter him, to use him, he thinks they have forgotten Andrea Wilborn and Stan Farr. Perhaps, because he has dodged the bullet so often, Davis feels blessed. And perhaps because so many seem to have a stake in his salvation, he now believes himself to be saved.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author