Editor’s Note: This story was first published in a different era. It may contain words or themes that today we find objectionable. We nonetheless have preserved the story in our archive, without editing, to offer a clear look at this magazine’s contribution to the historical record.

In my small East Texas town in the late ’50s, admitting that you went to Hockaday was just a cut above confessing that you had done time at the State School for Girls in Gainesville. From my provincial 15-year-old perspective in those tranquil days before court-ordered integration and busing, the only plausible reason for sending a girl away to boarding school was her delinquent behavior. Some boys in our town from wealthy families went east to Exeter or Andover for academic or social reasons, and other males with less promise got “straightened out” at Allen Academy, Peacock, or TMI; but the unruliest girl I ever knew was dispatched to Hockaday. And when she came home at Christmas and crashed a party at the Country Club, chain-smoked, drank Scotch on the rocks and performed a totally uninhibited dirty bop in front of the chaperones, we thought she was a wondrously sophisticated creature.

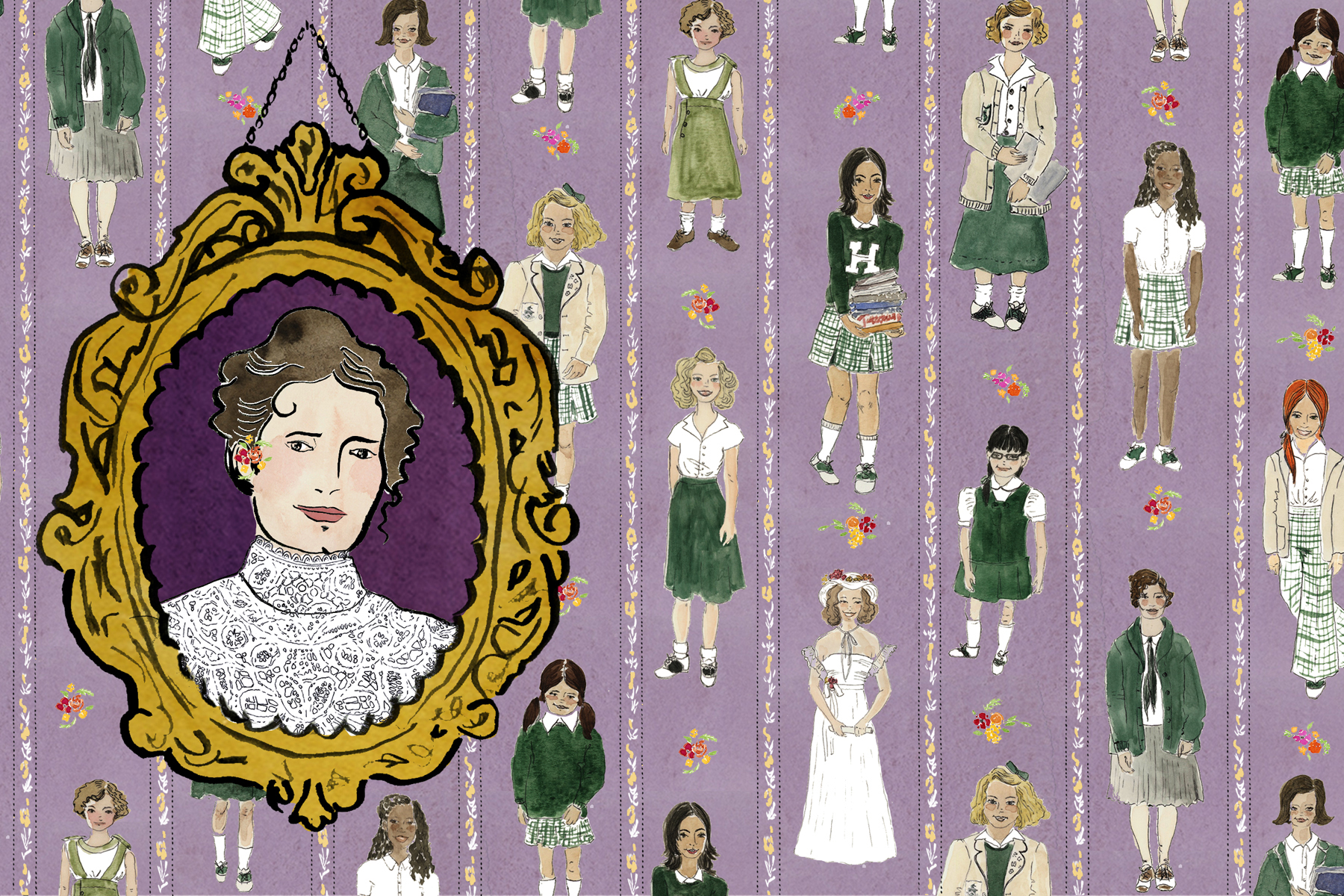

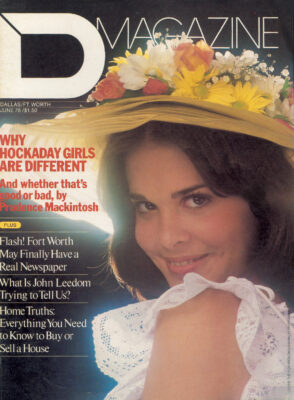

Imagine my surprise in the early ’60s to find Hockadaisies in my sorority pledge class at the University of Texas. Making my way at the big university as a small-town kid, I naively assumed that I would have a lot in common with small-town girls from equally distant provinces in West Texas or the Panhandle. I was wrong. My sisters from Wichita Falls were chicly coordinated by Neiman-Marcus, and to my amazement a girl from Amarillo had recently been photographed by the French fashion magazine Réaltiés. The photograph that identified me during rush was straight from the “Best All Round Girl” section of our Texarkana Tiger yearbook; their pictures with the wistful expressions, garden party hats, baskets of flowers and white organdy dresses looked to me as if they had been done by Renoir. I later learned it was Gittings. And besides daddies who dabbled in cattle or oil or just money, the main thing we did not have in common was the Hockaday experience.

As I got to know these young women, I quickly perceived that not everyone who had boarded at Hockaday was a behavior problem. Indeed, a Hockaday teacher would later say of my 1950s acquaintance, “Leg irons could not have restrained that child.” However, in all honesty, it did seem to me that these girls from Hockaday were decidedly less awed by the restrictions set by the university or sorority than I was. I would later realize that a great deal of energy in boarding schools is spent trying to get around school rules. So while I doggedly attended every class — even at 8 o’clock on Saturday morning — and worried about getting caught attending a party in an off-campus apartment or being locked out of the sorority house after hours, they blithely slept late, played a lot of bridge, obtained unauthorized snacks from the kitchen, or called the Chicken Delight delivery boy who agreed to attach boxes of chicken to a string of brassieres lowered from the second-story window.

If they did attend an early morning class, it might be in trench coat thrown over nightgown, a tactic learned at Hollins or Connecticut College on the “Texas Plan.” And if the sorority house door were locked when they chose to exit or enter, it was a simple matter to use the downstairs bathroom window. While we drones carefully memorized the sorority rituals, they made hilarious, irreverent parodies of the sacred ceremonies and held mock initiation rites with sounds of screeching owls in their rooms. They sometimes disappeared for weeks at a time to participate in the Tyler Rose Festival or to make debuts, and when the days of reckoning (exam week) came, these spirited grasshoppers seldom had to pay. Their rigorous high school preparation — or was it their inherent glibness? — enabled them to write English and history papers with minimal effort. Or, if worse came to worst, they knew where to get Dexedrine for an all-nighter before the exam. You didn’t have to go to Hockaday to know these things, but I think it helped.

In 1969 I had my chance to go to Hockaday as a teacher of eighth- and ninth-grade English. Although by that time I had acquired a measure of sophistication by working in Washington, spending a summer abroad, marrying an English major turned lawyer, and teaching four years in an Austin public school, I was still mightily impressed with the trappings of this legendary private school. My earliest letters to my parents after I assumed my teaching job recall a headmaster’s dinner with standing rib roast, Caesar salad, and créme de menthe pie. A buffet dinner with resident students and their parents whose nametags read like a Texas Who’s Who was no less sumptuous: chicken Kiev, ham rollups, green rice, plus silver trays of cold shrimp and fresh fruit. Dessert was a fluffy lemon mousse with toasted almonds. Clearly I was done with the gristly Sloppy Joe burgers and Jell-O of my public school teaching days. Gone, too, were the smells of every school building I had ever known. In the cool glassy elegance of this shiny modern building, there were no sweaty, scruffy children with unwashed heads, no odors of bologna or overripe bananas in sack lunches; the chalk dust disappeared from my chalk tray daily, and I never dispatched students to clean the erasers.

Of my students, I wrote home:

They seem younger than my public school students, perhaps because single-sex education does free little girls to be little girls longer. Seventh-graders still bring their jacks and jump ropes to school, and the playground monkey bars are full of eighth-graders during our morning break. Their enthusiasm for their Green and White athletic competition is phenomenal. They even elect cheerleaders for their teams. I suppose somehow I always associated cheerleading with the male-female mating ritual in public schools. I also had assumed that girls were sent to Hockaday to avoid that kind of inane activity. My eighth-grade girls are as giggly as I expected, but polite and manageable. Students at Hockaday stand when the headmaster or a faculty member enters the room. I still can’t get used to referring to the ninth-graders as First Form. This preppie labeling of the upper-school grades strikes me as a bit pretentious in Texas. In response to my suggestion that they inform me of any special problem they had that might hinder their success in the class, I received this note: “Mrs. Mackintosh, Please don’t let me bite my fingernails in class. I know you wouldn’t like to look at me chewing my fingers, so please help me to stop this awful habit.” Since my duties also include policing their manners at the lunch table, I will feel more like a governess than a teacher by the end of the year.

Occasional references during that year to “my horses” or “When we got back from Christmas in Guatemala,” or “the summer we rented the cottage in Provence” reminded me that, for the first time in my brief teaching career, I was no longer a role model. I often worried about the world history teacher who taught them about countries they knew first-hand but that she had only read about. I sometimes left at the end of the day wondering what business, with a B.A. from the University of Texas, I had teaching 13-year-olds whose life plans already presumed acceptance at Smith, Vassar, Wellesley, or Radcliffe — schools I had never heard of at their age. How different our educational experiences were. They would never know the frustrations of being taught world history by a football coach, nor would any of their classmates become grocery store checkers or beauticians after graduation. I once put aside the Odyssey to read my students a poignant Larry King short story from Harper’s about a carhop. Perhaps I reasoned that with little assistance from me, Hockaday girls might meet noble Greeks on ships, but never would they encounter a carhop with a boyfriend in Vietnam.

Miss Ela Hockaday, the school’s founder, had died 13 years before I came to Hockaday. Indeed, she had taken no active part in the administration of the school since retiring in 1947. But her influence was still apparent even to those of us who were too busy, or too young, to be interested. A tall fragile lady named Miss Bess Funk, whose primary function seemed to be greeting guests in the foyer and carrying the mail from office to office in a wicker May basket, was one obvious link with the past, as was Miss Kribs, a 1921 graduate and former Idlewild debutante who had been in continuous employ of the school for 48 years. I was warned about her the day I arrived. Everyone said the same thing. “Miss Kribs is worth her weight in gold. She saves the school so much money by accounting for every paper clip, but you might save yourself some sermons and tongue-lashings by purchasing your own supplies.” Miss Kribs wore her hair in a net and reminded me of a bulldog. Her seniority gave her certain liberties. I noticed at once that she called all of the teachers by their last names, drill-instructor fashion. More than once I saw the headmaster, Robert Lyle, stop dead in his tracks when she barked, “Lyle!” I checked my book orders for Miss Kribs more carefully than my students’ papers. Pity my colleague who went to the bookroom to fetch her classes’ copies of Lorraine Hansberry’s Raisin in the Sun only to find that Miss Kribs had ripped the front covers off. “Joyce [her last name], you didn’t tell me you were ordering books with coloreds embracing on the front. I cleaned them up as best I could,” growled Miss Kribs.

The most obvious legacies from the past at Hockaday are the Memorial Rooms — the Great Hall, the Memorial Dining Room, and a small library room — antique-furnished shrines from the Greenville Avenue campus now encased in the ultra-modem Welch Road structure. The rooms were not used much by students when I was there. Teas were held in the Great Hall, and the student council was allowed lunch in the dining room once a week, but the rooms had an off-limits museum quality that discouraged curling up in a wing chair to finish reading Anna Karenina. And to me, who at 25 was not untouched by the iconoclasm of the ’60s and who knew so little of Hockaday’s tradition, they seemed an enormous waste of money and space.

Eight years later, I now know that there are several things about Hockaday that you can’t understand if you are still, despite being warned, washing your grandmother’s hollow handle silver knives in the dishwasher; or letting the baby take Great Uncle Harry’s silver rattle to Six Flags; or yawning when your mother-in-law tries to explain her latest find in the genealogy charts. Part of Hockaday’s story presupposes that you know the importance of beautiful things and care about continuity from one generation to the next.

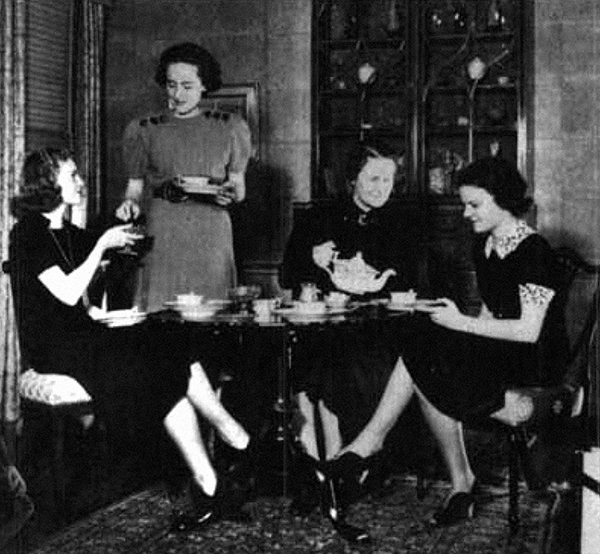

To learn about Hockaday from those who have known it the longest, you have to go to what is, by Texas standards, “the old money.” Their homes have warm, gracious living rooms or libraries where, despite your intention to be an objective journalist, you cannot resist becoming a relaxed guest. Tea is served in cups that, like grandmother’s knives, must be hand-washed, and the cookies are crisp homemade almond tuiles. There is an assumption that everything should be as lovely as possible — not ostentatious or extravagant, but simply harmonious and elegant. And in the homes of these early alumnae and benefactors, it is.

In the memories of some of these alumnae, and even in the Hockaday history, a somewhat flowery tome published in 1938 to commemorate the school’s 25th anniversary, Miss Ela Hockaday looms larger than life. “To this day,” one alum of the ’20s recalled, “I still remember Miss Hockaday chiding me about being on time. Once when I came downstairs late for dinner once again, Miss Hockaday actually cried. I’m very punctual these days.” Over and over again, I heard women say, “She was my mother’s very best friend,” or “She was such a lady.” That she was the consummate lady, I have no doubt. That she was anyone’s closest chum is debatable.

Ela Hockaday was a native Texan, daughter of a rigid scholarly schoolmaster who had an academy in Ladonia. Her mother died when she was a child, and her older sister aided their stern father in caring for her. Except for a brief stint at Columbia University, her formal education was obtained in Texas teachers’ colleges. She gained some prominence as a teacher by taming ruffians in the Sherman schools and went on to teach in Durant Normal School before coming to Dallas. I assume her unerring taste and sense of decorum were inherent. On the recommendation of M.B. Terrill, whose Terrill School for boys was a forerunner of St. Mark’s, Miss Hockaday was summoned in 1913 by Dallas citizens H.H. Adams, Ruth Bower Lindsley, and “others” to establish a college preparatory school for girls.

Miss Hockaday’s job was to see that the confidence Dallas women had about their appearances would not be undermined when they opened their mouths.

Noted for her quick, incisive mind. Miss Hockaday must also have been a capable politician. “The perfect casting for the Virgin Queen” is the way Stanley Marcus remembers her. In no time at all, she had assembled a privy council of Dallas’ most powerful civic leaders that included names like Charles Huff, R.W. Higginbotham, Charles Kribs, and Herbert Marcus. (Later Hockaday boards would include Karl Hoblitzelle, Jake Hamon, Eugene McDermott, and Erik Jonsson.) Stories abound about these men leaving conference rooms to do Miss Hockaday’s bidding. Some of these men provided legal advice, others had financial connections and business sense to offer. Most of them also had daughters. Herbert Marcus had only sons, but it is easy to see why Miss Hockaday sought his counsel. At a testimonial for Herbert Marcus in 1937, she said, “Mr. Marcus has carried artistic value into whatever he has done.” In a sense, Miss Hockaday and Neiman-Marcus were in similar businesses. In that same testimonial speech, she went on to say, “The women of Dallas have always felt grateful to Mr. Marcus for giving them utter confidence that their clothing was appropriate and tasteful wherever they were, whether in Dallas or in a city that was a world capital.” Miss Hockaday’s job was to see that the confidence Dallas women had about their appearances would not be undermined when they opened their mouths.

With meager financial backing, Ela Hockaday opened her school to 10 students on September 25, 1913, four days after she arrived in Dallas.

In those few days, she had located a house on Haskell for the school, hired her teaching colleague and friend Sarah Trent as faculty, and devised a curriculum that included mathematics, English, history, Latin, German, and French. Twenty-eight years later, the Christian Science Monitor noted:

Miss Ela Hockaday has accomplished the so-called impossible. She has made a private school pay its own way, unendowed and not tax supported … Today [ 1941] she is president and active head of a school with a student body that numbers 450, a staff of 83, and a plant approaching a million dollars in value, still unendowed, still the complete servant of its president.

The lack of endowment and Miss Hockaday’s iron-clad reign over the first 30 years of the school’s life, so lauded by the press, would plague her successors. To this day, headmasters at Hockaday are regarded by some who were intimately acquainted with the school in its early years as unworthy pretenders to the throne.

Hockaday quickly outgrew the small house on Haskell and moved to a 9-acre portion of the Caruth farm on Greenville Avenue and Belmont, which then was the outskirts of Dallas. From alumnae scrapbooks, I can piece together a pleasant picture of Georgian buildings, Miss Hockaday’s antique-filled cottage, rose gardens, a swimming pool, playing fields manicured but frequently scarred by hockey sticks, and “the pergola.” (I confess I had to look it up too.) In a description of the grounds at Hockaday for the 1938 history, Isabel Cranfill Campbell (’27) writes:

Way back in the beginnings of Hockaday, there was the pergola … an inspiring place always, with its sweeping view of the campus which has twice received a civic prize for beauty. Here the yearly round means an exchange of blossoms — forsythia and redbud at winter’s end, jonquils in the new spring grass, valiant zinnia borders at midsummer, and autumnal chrysanthemums. Only the clematis vine that wreathes the pergola itself is renegade. For, constant as the Northern Star, it refuses to bloom until just after Commencement, when school is out and it must waste its sweetness on comparatively desert air. Still and all, such happy progress has been.wrought here, the school has grown so lustily and well in all its parts, that I for one, expect one day to see the clematis change its stubborn mind and send out white fragile blossoms to honor the graduates of Hockaday.

With such florid prose in my head, it was depressing to walk around the Belmont Towers on Greenville, which rise now where Hockaday stood until 1961. Only a hedge from the old school remains. However, some of the merchants in the area haven’t forgotten Miss Hockaday. Bill Clark of Clark’s Fine Foods, the market that provided Hockaday’s food on the old campus, still recalls Miss Hockaday inviting him to her cottage to meet Eleanor Roosevelt. With a sheepish grin, he also recalls, “I had a bad habit. Well, I guess I still do. When I’m making change, I lick my thumb to separate and count the dollar bills. I can still hear Miss Hockaday saying, ’Bill, don’t do that. You never know who’s had their hands on that money.’”

If Miss Hockaday felt she could inflict her standards on her grocer, you can imagine the scrutiny she gave her students. Her school was begun in an age when, at least in Texas, there was no ambivalence about moral imperatives. To understand Hockaday’s early days, you have to assume the 19th-century mentality of its founder. All things were achievable with self-discipline and hard work. M.B. Terrill of the Terrill School was widely admired in those frontier days as a headmaster who brought student transgressors to swift and terrifying justice. Although Miss Hockaday did not pounce on her girls and belabor them with blows as Terrill did his boys, she was a stern disciplinarian nonetheless. One long-time associate of Hockaday admitted that there were times when she wanted to stick her tongue out at the stiff headmistress. “She was absolutely uncompromising in her standards, and you either embraced her code or you had nothing to do with her school.”

So that she might detect any student infraction of the “no smoking” rules on the Hockaday campus, even the gardeners had to comply. Maids who cleaned the resident students’ rooms and served the seated meals were to be impeccably uniformed. “After cleaning up Trent House, we were supposed to get ourselves cleaned up, put on our formal serving uniforms, and be sure our shoes were shined. Everybody ’dressed’ for dinner at Hockaday,” Exie Tunson, who worked as a maid for Miss Hockaday for 30 years, proudly recalls.

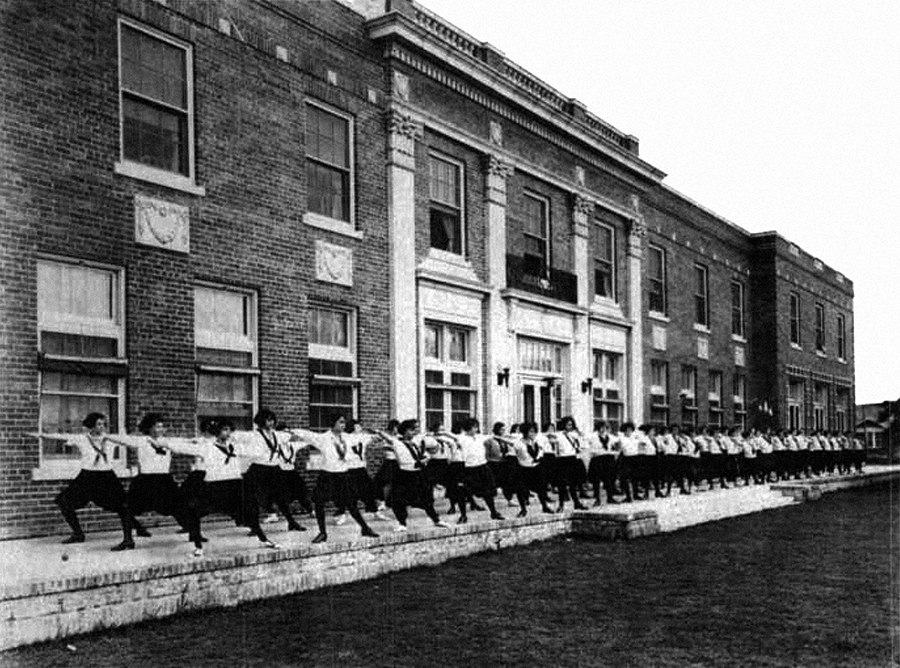

Not only did Miss Hockaday prescribe the schoolgirl’s uniform — middy blouse, bloomers, black stockings, and high-top brown leather “cow shoes” — but she passed judgment on the girls’ street dresses and ball gowns. Delivery trucks from Neiman’s sometimes brought the long boxes with prom dresses first to Miss Hockaday’s cottage. At the tea dances, if she detected alcohol on the breath of any young man, he was blacklisted from further participation in Hockaday social functions. Indeed, some of the earliest graduates recalled that no men were allowed at dances at all. The girls danced with each other and, to this day, some admit, they have to consciously remember not to “lead.”

Hardly anyone remembers being scolded by Miss Hockaday; it simply wasn’t necessary. Her awesome presence was usually enough to correct any irregular activity. Exie Tunson remembers serving coffee to the faculty after dinner in one of the rooms not far from the study hall. “We’d close the doors and all have a ball in there,” Exie recalls. “One night, Miss Winifred Clopton was playing the piano, and I said, ’Miss Wini, play the “St. Louis Blues.”’ And boy she wailed away on the ‘St. Louis Blues.’ And Miss Gulledge and Miss Dolly and a bunch of us, we were all trying to sing low all about ’got the St. Louis Blues,’ and Miss Hockaday opened the door. Oh boy! It was like a bunch of roaches when you turn on the light.”

A similar story comes from an early boarding student. She and her roommates dared to sneak back into the kitchen after lights out for an additional serving of ice cream. Just as their spoons were digging into the large ice cream can, the lights went on. There stood Miss Hockaday in her bathrobe with flashlight in hand. “Oh, girls,” she said sweetly, “You must still be hungry. Well, this is certainly no way to eat. Put those spoons down.” With that she summoned a maid, instructed her to put on a uniform, set the table with linen place mats, napkins, crystal bowls, and spoons. The errant boarders were led to the dining room and required to choke down two bowls of ice cream before returning to their rooms. No scolding. Just a presence powerful enough to scotch any signs of rebellion within her realm.

Those were the days when rebellious girls seamed-in their middy blouses with safety pins or waved at the boys from the Terrill School who circled the campus and sometimes left notes in the columns out front. Surprisingly enough, some of those with the safety pins in the seams of their middies have the warmest recollections of their days at Hockaday. “She gave me hell,” says one who is still something of a rebel, “but I admired her because she was tougher than I was, and she never held grudges. She came to my wedding even though I married a man she had blacklisted for responding improperly to a tea dance invitation. Actually his roommate at SMU had responded to the invitation for him — on toilet paper.”

Miss Hockaday attended a lot of weddings. And even the husbands of Hockaday graduates can often tell you what Miss Hockaday sent as a wedding gift. The wives can also tell you how it was wrapped and whether she brought it personally or had Sam, her chauffeur, deliver it. Her gifts invariably became family treasures. An inveterate collector, she almost always gave pieces of antique silver, sometimes from her own collections. “Thanks to Miss Hockaday,” one early graduate says, “many of us who graduated in the ’20s are ‘silver and china rich.’ The Depression was already hitting Europe, and many fine European families were having to liquidate their assets. Miss Hockaday encouraged us to invest in these treasures.” Always a frugal woman, Miss Hockaday supported herself during lean years with her antique collections. “If she needed a little money,” Exie Tunson says, “she’d just sell off a little Rockingham china.”

If Miss Hockaday seems a little stuffy, it may be because I had such difficulty getting what I felt to be a complete picture of her. Even those graduates who returned as married adults to have a dinner at her cottage admit that they never quite felt relaxed enough in Miss Hockaday’s presence to partake of the preprandial martinis and cigarettes she proffered. If she had any sense of humor, no one I talked with could specifically recall it. They remembered her intelligence, her probity, her self-discipline, her kindness, her concern for each of her students, her impeccable taste, but no one seems to remember a time when she took herself less than seriously or displayed any vulnerability. Helen B. Callaway of the Dallas News recorded a favorite story about Miss Hockaday in a 50th anniversary story in 1963:

On the third day of World War II, the news wire had chattered out a sizzling story that was to send American blood pressures soaring: A German submarine had torpedoed and sunk the British liner SS Athenia, with 1,418 people aboard, including many from the United States. A number were Hockaday students.

Reporter Fred Zepp called Miss Hockaday late that night, rousing her from sleep to break the news of the stunning tragedy at sea.

After the briefest of pauses. Miss Hockaday commented: “That seems highly irregular.”

Perhaps the maintenance of very high standards always requires a little stuffiness. And sometimes Miss Hockaday’s highly valued code of self-discipline went to extremes. The story is told of a Latin teacher, a spinster as most teachers were in those days, who came to Hockaday from Virginia. She brought with her the exquisite antiques accumulated by generations of her aristocratic forebears. She was just the sort of refined woman Miss Hockaday valued as a model for her girls. “Self-control is the mark of a gentlewoman,” preached Miss S. And she demonstrated it most dramatically one day when a breathless student interrupted her class to announce that Miss S’s apartment was on fire. “Is the fire department there?” Miss S. calmly asked. “Yes,” replied the excited student. “Very well, class, we will continue our declensions.” The teacher lost everything in the fire and was generously taken in by a day student’s family for the remainder of the term. That she hanged herself after graduation that year is a sad commentary on the virtues of gentlewomen.

The parents who brought Miss Hockaday to Dallas wanted a college preparatory school for their daughters, and she obliged by sending members of her first graduating classes to such schools as Barnard, Smith, Radcliffe, Wellesley, Mount Holyoke, Stanford, and Vassar. As there was no ambivalence about proper conduct for a young lady, Miss Hockaday had no lack of conviction about what belonged in a woman’s education. She based her school on what she called the Four Cornerstones: Scholarship, Courtesy, Athletics, and Character. According to a 1928 graduate, “Hockaday gave me the nuts and bolts for building a very satisfying liberal arts education. In those days we were never asked to do anything particularly creative. There was too much to be learned, and I guess we were vessels to be filled. I know that’s not a popular educational concept today, but I’ve never had any regrets about the sort of discipline that Hockaday gave me.” “A passion for thoroughness” was the way a later graduate phrased it. To Miss Hockaday’s credit, in an age when women were under no pressure to pursue careers, a surprising number of her graduates gained some national attention as artists, writers, archaeologists, and musicians.

As early as 1935, Miss Hockaday saw fit to bring Judge Sarah T. Hughes to speak to her junior college students on “A Woman’s Opportunities Today.” Just what those opportunities were is suggested in these remarks by a student who recorded Judge Hughes’ visit in the 1938 Hockaday history:

As a result of her talk, my typewriting took on new significance, and shorthand was no longer an unintelligible offspring of the Morse code. Later Miss Trent asked her psychology class how many planned careers. Still under the inspiration of Judge Hughes’ talk, every hand in the room was raised. The students fully expected a woman like Miss Trent with fifty years of successful teaching behind her to endorse their decision. Instead, she chuckled and said, “I’m sorry; I wanted you all to get married and have children.”

And that is precisely what most of them did. Even many of those Hockaday scholars who showed early promise in their chosen careers willingly exchanged their ambitions for what society regarded as woman’s chief service, motherhood and homemaking. Many of them married very well, and as one put it, “never again had the fire in my belly that would have fueled a career.”

Hockaday was undoubtedly offering the best education available for women in this region, but, for all its scholars, it is still remembered by most Dallas citizens as a finishing school, “a very adequate education for the gracious life.” A private school in those days, by its very nature, was designed to serve a homogeneous segment of the population. Most of the parents Miss Hockaday dealt with knew each other and shared a common purpose in sending their daughters to her school. That is, “Educate my daughter to be a woman of taste who moves gracefully in any social circle. Give us cultured young ladies who will raise the standards of this community by supporting the arts, daughters with a sense of noblesse oblige who feel a responsibility to upgrade this growing city.” To that end, Hockaday girls devoted some time to assisting social workers “to make certain that the neediest, most deserving, and cleanest families received help” at Christmas. “By the contacts,” the 1938 history notes, “the girls saw with heartfelt sympathy and keen interest how the other half lives.”

They were also given a thorough grounding in the social graces. Many remember Miss Miriam Morgan, who joined the faculty shortly after the school opened, as the ultimate authority on manners. The Hockaday history even records table manners contests with score cards. Report cards as late as 1948 show that the girls were being graded with an S (Satisfactory) or an I (Improvement Needed) for “knows the meaning of joy’’ or “speaks in conversational tones” and of course, “behaves in a ladylike manner at all times.” “Courtesy caps,” green and white beanies, were still being awarded in the ’60s.

“Finishing” also meant travel. For nearly a decade between the two World Wars, Hockaday sent travel classes abroad. Accounts of these trips are frothy confections of send-off parties at the Waldorf Astoria, orchid corsages, first-class staterooms aboard the Vulcania, raucous Spanish sailors in Seville, Christmas in St. Moritz with the Cambridge ski team, tea with Lady Astor, an audience with the Pope, the coronation of George VI, Mussolini reviewing his troops in the Villa Borghese, chocolate croissants, and French classes at the Sorbonne. Small wonder that for some women Hockaday was the high point of their lives.

Even those who stayed at home were treated to the museum-quality antique collections of Miss Hockaday’s cottage, as well as a steady stream of world-renowned personalities as diverse as concert artist Josef Lhevinne, General Jonathan Wainwright, and later the Reverend Peter Marshall. I am always a little amused when Hockaday graduates point proudly to the visit of Gertrude Stein and her companion Alice B. Toklas in 1935. For one thing, it suggests that Miss Hockaday was willing to suspend her moral imperatives when it came to artistic guests, but I also wonder how many people who met Miss Stein in 1935 had the slightest idea of what she was talking about. “Fusing being with the continuous present”? Indeed. One Junior College student candidly admitted, “Miss Stein was reading from one of her books, a poem concerning “then” and “when.” She was very kind, though, and seemed not the least disturbed at our evident lack of understanding of her poems.” And what did Gertrude and Alice think of Hockaday? Alice B. Toklas tells us in The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook:

On to Dallas where we went to stay with Miss Ela Hockaday at her Junior College. It was a fresh new world. Gertrude Stein became attached to the young students, to Miss Hockaday, and the life in Miss Hockaday’s home and on the campus … The only recipe I carried away was for cornsticks, not knowing in my ignorance that a special iron was required in which to bake them. But when we sailed back to France in my stateroom one was waiting for me, a proof of Miss Hockaday’s continuing attentiveness. What did the Germans, when they took it in 1944, expect to do with it? And what are they doing with it now?

So what does all of this have to do with Hockaday in 1978? To the casual observer, perhaps very little. In one day I see a dozen or so students sprawled in front of a TV watching All My Children in Tarry House, the senior lounge. Mrs. Lively, the executive housekeeper since the early ’40s, is murmuring that the girls are dropping tangerine seeds in the Great Hall. A blue-jean-clad teacher saunters by on her way to the ceramics studio. A sixth-grade class struggles with computer language — “let” statements, “destructive read-ins,” and “content read-outs.” The headmaster shakes hands with his students as they enter school for the day and prides himself on knowing most of their names, but for the rest of the day he must concern himself primarily with Hockaday’s greatest worry: money. Does Miss Ela live here anymore?

The changes have come gradually. Miss Hockaday, convinced by her “privy council” that her school would never survive estate taxes, agreed in 1942 to transform it into a publicly owned institution operated by a board of trustees. In an emotional letter, she gave the school theoretically to her alumnae. Although she continued to live on the campus, Miss Hockaday officially retired in 1947, just as the second generation was entering Hockaday. She greeted these daughters with the same scrutiny she had given their mothers. One second-generation Hockadaisy recalls her first encounter with Miss Ela. “We had driven in from Amarillo, and my mother saw Miss Hockaday walking across the campus. ’Miss Hockaday, I want you to meet my daughter.” Miss Hockaday took one look at me and said to my mother, “Oh, Imogene, how could you have allowed this child to dye her eyelashes?’”

Dyed eyelashes were the least of Hockaday’s worries in the 1950s. In addition to the second generation, the school was acquiring a new and less restrained constituency — the oil people. Hockaday was becoming a status symbol to be collected along with oil wells, Neiman’s labels, and Cadillacs. Jett Rink’s daughters came from the small towns in West Texas and from oil towns in Louisiana and Oklahoma to fill the boarding department at Hockaday. Some of these young girls arrived with special instructions from their parents that the child not be allowed to see any newspapers dealing with her family’s fabulous wealth. Others were less discreet. “Somebody was always getting out of class to go donate a building to SMU,” recalls one ’50s alum. She also recalled that the “oil” girls were likely to be dripping in jewels at the dances, and many of them had fancy cars stashed somewhere in town. “Somebody in my class got a Cadillac with a bar in the back for graduation,” remembers another. According to these alums, the main recreation for boarding students on Saturday was shopping all day at Neiman-Marcus. “I once saw a boarder buy seven vicuna sweaters in one afternoon, just because she was mad at her daddy for sending her away from her boyfriend back home. My mother said, ‘Miss Hockaday would never have permitted that.'”

Miss Hockaday died in 1956, and gradually the teachers who had worked closely with her retired or lost their earlier impact. Some of these second-generation daughters had heard so much about Hockaday that by the time they actually enrolled, they were disappointed. “My mother had told me what Miss Grow, the Latin teacher, would say on our first day of class. And she did give the same speech about how you came into this world with only your name … and what you do with that name is so important. That may have inspired my mother’s generation, but I kept thinking how terrible it was that in all those years Miss Grow had never changed. She said the same words, fought the same Gallic wars, and it never occurred to her that most of us could hardly wait to change our names. She was Miss Grow forever, but she wasn’t anyone I wanted to emulate. I remember that she spit on the blackboard when she talked facing the board and had to erase the spit. Isn’t it awful to remember that? I also remember seeing her squat one day to retrieve a pencil. I was shocked momentarily to see that she had knees just like the rest of us. Unlike my mother, I was a terrible Latin student, so I spent most of the year hearing Miss Grow say, ‘Oh, Virginia. I’m so disappointed in you.’”

Like them or not, teachers like Miss Grow had the power to withhold school honors or to vindicate you when you were falsely accused. One alumna recalled being put “on report” for smoking in the restroom. “Miss Grow looked me straight in the eye and said, ‘Did you smoke?’ Everyone knew you couldn’t lie to Miss Grow, so when I said ’no,’ the matter was dropped.” Some of these teachers must have been rather like maiden aunts whom you never really liked, but who had a disproportionate hold over your life. As another graduate said, “I still have the haunting feeling that because I couldn’t live up to Miss Grow’s expectations, somewhere it is permanently recorded that I was a failure.”

In 1961 Hockaday moved north to a very barren hundred acres on Forest Lane and Welch Road. The school’s original patrons had moved north long before, leaving the gracious gardens of Swiss Avenue and Munger Place in a state of decay. Dallas was growing rapidly and no longer looked to a few families or a school to be the arbiters of taste and culture. Some alumnae reacted violently to the modern edifice on the new campus. One says it still reminds her of a Green Stamp redemption center, and others insist that travelers sometimes mistake it for a motel. The fact is, Hockaday on Welch Road is a swanky-looking school. (Swanky is a word I’m sure Miss Hockaday never used.) And when someone wants to point a finger at a rich girls’ school, Hockaday, with its glassy atrium, is an easy target.

Ironically, this reputation for affluence is one of Hockaday’s biggest problems. While it has attracted the daughters of the wealthy, Hockaday has never been a rich school. Miss Hockaday lived from tuition to tuition, charging the groceries and other services until the checks came in. Her teachers were paid minimal wages, especially when you consider the hours they were expected to work overtime chaperoning and supervising. She always had someone like Miss Kribs to see that every square inch of carbon paper was used before a new sheet might be issued. Forty-watt bulbs or less were de rigueur in the hallways of her school, and even Exie Tunson will tell you, “I only worked for a rich lady once. The rest of the time I worked for working people like Miss Hockaday. She sure knew how to cut corners.”

“I’m not sure how much longer we can afford the gentility,” says current chairman of the board Rust Reid. Indeed, Hockaday today is like a very refined lady who has heretofore considered it indiscreet to air financial problems, but who has in reality been patching her undergarments for years. Now, even Hockaday’s outer garments need patching.

The problem is, Hockaday has no funds for the maintenance of the swanky buildings that cost $4 million to build in 1960, but now would cost $12 million to replace. Sure, Hockaday has some generous patrons, but there are few philanthropists who want a bronze plaque on the air conditioning repair bill, especially when there are more exciting plans for a gym and a new library on the drawing board.

When Glenn Ballard, the present headmaster, came to Hockaday in 1972, the school had only $130,000 in endowment, which was really designated for faculty retirement benefits. In the past three years, thanks largely to the efforts of Ballard and past chairman of the board Ashley Priddy, the school has been able to raise $3.5 million in donations and pledges. That sounds like a hefty sum until you hear that schools like Andover and Exeter have endowments of $70 million. According to Hockaday’s development director, the school needs an endowment of between $10 million and $15 million. Without such an endowment, the school is at the mercy of its donors. For example, Hockaday’s library space has been woefully inadequate practically since the building on Welch Road was erected; a recent professional study also showed that the gym facility is now inadequate for Hockaday’s comprehensive and growing physical education program. Although the library need has been around longer, in sports-conscious Dallas money to build squash courts, running tracks, and locker rooms is apparently easier to come by these days than money for study carrels.

A little checking reveals that Hockaday is in reality no poorer than most regional private schools. St. Mark’s has about the same current endowment, and its operating costs are only slightly less than Hockaday’s. However, a great portion of Hockaday’s budget must be allotted for its boarding department. Hockaday must serve three meals a day and keep its air conditioning running continuously. St. Mark’s has only day students. Hockaday also suffers because it is a girls’ school, and its graduates are not necessarily breadwinners. Many women complain that school donations invariably go to their husbands’ alma maters. And even those women who do control ample pursestrings are likely to say, “Oh, Hockaday doesn’t need any money. I’d rather put my money where it’s really needed.” Parents who are paying Hockaday’s present tuition, which went up 7 percent for 1978-79, are unlikely sources for more revenue. Current tuition at Hockaday ranges from $1,075 for the preschool (4-year-olds) to $3,205 for a senior day student. Resident students are paying close to $6,000. However, parents of Hockaday students do tend to contribute generously to the Annual Giving campaign, since it is a tax-deductible way of ensuring that the school won’t need to raise tuition further. The campaign raised $325,000 in 1977, more than any other girls’ school in the country, but Hockaday has to use it to bridge the gap between tuition and actual operating expenses.

What motivates people to give to a school like Hockaday? Male institutions can always point to the professional success of their graduates as proof of the school’s value. The success of women, beyond college acceptance, may be harder to measure. Some people may give to a school for nostalgic reasons. Even though they were expensive to install, Hockaday could not leave those Memorial Rooms out of its modern structure. There had to be something to tie the alumnae to the new campus.

Although Miss Hockaday was always a forward-looking educator, she could not have conceived of the pressures that would come to bear on her school. The school’s constituency has broadened so that there could never be a consensus among parents about what the school should be. The granddaughters of her original graduates are now enrolled in the school. And the second generation of oil money is there. And there seems to be an inordinate number of professional bourgeoisie. One-third of the second-grade class have doctors for fathers. Integration, busing, and experimentation in the public schools have brought still another set of parents to Hockaday. These parents are not necessarily seeking social prestige, or Miss Hockaday’s ideals; they simply want a safe, decent school in which to park their daughters until the public schools settle down. These are, for the most part, public-educated parents who may have little interest in sending their daughters east to college. In fact, they may be a little distrustful of Hockaday’s college counseling. Enrolling her 5-year-old daughter in the preschool, one mother actually asked, “Now you’re not going to make her marry a Yankee and move away from Dallas, are you?”

In addition to these day students, the school also has a large number of boarding students from South America, as well as an obligatory sprinkling of black students and Mexican-Americans. A look at the ZIP codes in the student directory reveals that Hockaday’s day student body converges from all directions. Seventy-eight students come from Highland Park, eight from Oak Cliff, six from the old neighborhood near Greenville, and 249 from the sprawling North Dallas neighborhoods surrounding the school. Still others commute from Garland, Mesquite, Farmers Branch, etc. About all you could safely say these families have in common is the ability to pay the tuition, and quite a few are receiving partial scholarship aid.

While Miss Hockaday and her early faculty members (Miss Trent, Miss Morgan, Miss McDermott) were certainly distinct personalities, they had a common bond of spinsterhood and total dedication to the school. Today the faculty and staff at Hockaday are as diverse as the families of the children they serve.

Mrs. Lively, the executive housekeeper, is a lovely Russian lady. She takes me on a tour of the Memorial Rooms and with her charming accent recalls. “How lovely it was! Miss Morgan would ring the bell, and the girls would go quietly into the dining room. The tables were set with the linen doilies and nice silverware. The girls, they were so polite. They let their teachers go first. Now,” she says with a sigh, “they are not so polite. It is all so fast, you know, whoosh-whoosh, in and out. Ah, this cafeteria. Miss Hockaday would not like it. The boarders have a seated dinner only once a week. In the old days, it was every night. And there were beautiful flowers and always singing in the Great Hall. Oh, Miss Hockaday loved flowers. I could always find something blooming on the old campus to make a nice centerpiece. Here, if I don’t see that the bulbs are planted, no one else will. They don’t care so much anymore. There is not time or money for the lovely things anymore.”

In stark contrast to Mrs. Lively is Peter Cobb, the new head of the Upper School. Cobb is 30ish, frizzy haired, athletically inclined, and certainly handsome enough to provoke a few crushes among his adolescent students. Cobb has a Master’s of Divinity from Union Theological Seminary in New York, where he admits he was something of a radical during the ’60s. Coming to Hockaday from the Master’s School at Dobbs Ferry, N.Y., Cobb says only half-facetiously, “Well, one of the problems we have here is that the girls are too polite.” He quickly qualifies his statement by assuring me that he is by no means out to destroy the graciousness of southern womanhood. As a matter of fact, after his years on the east coast, he’s rather taken by it. But he feels the school has a tremendous responsibility to prepare girls for careers that may demand aggressiveness, initiative, and a willingness to take risks. I couldn’t help smiling at the irony of Hockaday’s teaching girls to take risks when so many of their parents sent them there to be safe.

It is also curious that Miss Hockaday herself must have successfully blended the aggressiveness and graciousness in her career, but when she retired, she chose a man, Hobart Mossman, to succeed her. Indeed, for all of its talk about limitless opportunities for women, Hockaday has not had a headmistress since Miss Hockaday. For that matter, with the exceptions of the foreign language and physical education departments, which have no male teachers, all of the Upper School departments are headed by men.

I also asked Glenn Ballard, Hockaday’s personable headmaster, about possible conflicts in trying to produce professionally successful young women in a southern girls’ school. Headmasters of private schools are inevitably able public relations men, and any reporter has a tendency to discount their statements as boosterism. Nevertheless, Ballard says the broadening of Hockaday’s constituency has helped provide profession-bound girls with models to emulate. “The mothers of Hockaday students now run the gamut from those who wear white gloves and go to tea parties or luncheons every day to moms who have retained their maiden names and have careers of their own. The mothers, on the whole, have a better grasp of what it is we’re trying to do, and they are for the most part supportive. The fathers tend to relish their daughters’ growing independence, but experience more ambivalent feelings. Occasionally a father admits that he wishes she’d just imitate her mother.” Both Cobb and Ballard insist that they find working in a girls’ school so satisfying that they never long for a night out with the boys.

The faculty, like any contemporary school faculty, can be broken down into three or four types. There are the teachers who basically like kids and who never count the hours they spend counseling with them after school. There are the serious scholars who enjoy the students who share their passion for a particular subject. And perhaps at schools like Hockaday there are some who stick around primarily because they enjoy the prestige of association with prominent parents. How about a parent conference with Harding Lawrence and Mary Wells’? As at any school, there are the older faculty members who tend to believe that they are the only ones doing any real teaching. They lament the fact that their classes seem to be something to occupy students’ time between extracurricular activities.

Some recall sweeter days when the cultural vibrations went from Dallas homes to the school. One teacher remembers days when parents had poets or musicians visiting in their homes and would agree to share their friends with the school. “Now,’” he says, “it seems to be the other way around. The intellectual climate in Hockaday homes is not what it used to be.” This spring, a Broadway musical performance seemed to be causing a bit of rancor among teachers and parents. One parent complained, “I was glad my daughter was chosen to be in Mame, but after the time she spent on rehearsals, I began to wonder, ’Did I send her to Hockaday to learn to be a Las Vegas showgirl?’”

Some of the younger faculty members seem to be imbued with a frontier spirit. Teaching in a girls’ school is no longer a second-class job. Hockaday is sending girls to Stanford, Princeton, Yale, Harvard, Rice, and M.I.T. The curriculum is demanding, and the faculty seems increasingly distinguished academically. Nobody teaches at Hockaday for the money. Salaries range from $9,000 for a beginning teacher to $21,000 for a department head, plus grants for summer graduate work. Nevertheless, teaching at Hockaday is a luxury, especially if you’ve ever taught in a public school. The girls are rather easily motivated, and the small class sizes make the teacher-pupil relationship potentially very rewarding. “Where else,” says dean of faculty Dr. Tezzie Cox, “could we read 10 Shakespeare plays in one year and write papers on each of them?” Private school teaching can provide all of the stimulation of teaching at the college level without any of the headaches of “publish or perish.”

There are things about Hockaday you can’t understand if you are still, despite being warned, washing your grandmother’s hollow handle silver knives in the dishwasher.

But there are also awesome responsibilities and pressures in teaching at Hockaday. There is the ego involvement of successful, upwardly mobile parents who want to believe that Hockaday can work miracles. “They pay for it,” says a faculty member, “so by golly, you figure out a way to get their baby through. If she can’t handle the curriculum you’ve set up, then you change it.” Parents are also concerned about Hockaday’s maintaining traditional standards in the face of grade inflation everywhere else. “’I sent my daughter to Hockaday because it is a college preparatory school,” says one parent, “and the irony of it is that the C she’s making in a Hockaday English class, where no grade higher than C is being given, will probably knock her chances for the college of her choice.”

What is it like to be a student at Hockaday? Some girls will spend 14 school years there. Hockaday recently added a preschool for 4-year-olds, and since many people seem to believe that once you’re in, you’re in for good, there is considerable competition even at that early age. Miss Hockaday used to interview each prospective student personally. Now an admissions office handles the interviews. “When I interviewed at Hockaday for the seventh grade, I remember being asked what college I planned to attend. I think I said Smith because that’s where my mother went,” one graduate recalls. The pressure is on.

Most of these girls are the daughters of achievers, and they know that their parents have high expectations. As one lower-school teacher put it, “I sometimes worry that these little girls never get to do something just for the fun of it. Their lives are so programmed. They take piano lessons, gymnastics, go to choir practice, get tutored in math or reading, or go to ballet. By the ninth grade or even earlier, they are worrying about college acceptance. They are told that good grades alone will not assure them of admission to a prestige college. So now they must spend their summers ‘productively,’ teaching deaf kids, going to Andover summer school, or learning photography — anything that will make them an ‘attractive package’ when their application crosses the college admissions desk. It seems as if they are always living their lives in preparation for the next hurdle. Some are even taught to be socially calculating at a very early age. I worry that they never get the chance to just be — to just lie in the sun and let the wind tickle their toes. It may sound like heresy, but I think a little benign neglect might be healthy for some of them.”

What do Hockaday girls look like? They’re mostly green and white, and beyond seventh grade have waist-length blonde hair, gold ear studs and saddle oxfords and wear their green sweaters tied around their waists. When I asked several of them what misconceptions they thought most people had about Hockaday, they responded, “Tell them that we’re not all just a bunch of rich girls.” “And we’re not a bunch of lesbians, either,” giggled another. The green and white uniforms do go a long way toward concealing any economic differences in the student body, but as one recent graduate told me, “Aw, everybody knows who’s got money and who doesn’t. Look at the parking lot. You know who drives the Mark IV with ’Molly-16’ on the license plate.” And there are subtle ways of distinguishing yourself even in a uniform — Gucci keyrings and Rolex watches. One alum remarked, “I wouldn’t mind being black or brown or green at Hockaday; I’d just hate to be poor.”

After being at Hockaday for a few days, I think I’d mainly hate to be stupid. I talked with the mother of a Mexican-American student who is certainly, by Hockaday standards, “less well-off.” She did not feel that her daughter had suffered any discrimination at Hockaday. “She knows who she is. She doesn’t try to compete socially, and quite frankly she finds the activities of some of her very affluent classmates rather entertaining. Although there is certainly competition at Hockaday for grades and in athletics, there also seems to be some very healthy pride in each others’ achievement. My daughter won an award and found her locker decorated with ribbons and notes of congratulations. She really appreciates that esprit de corps.” In all fairness, it should be noted that this particular student is also one of the brightest kids at Hockaday. Her mother did go on to say that she was also pleased to hear Peter Cobb talking to parents about the girls’ need to develop life skills. (“They can program a computer, but can they put the chain back on their bikes?” he once asked.) “I wanted to tell the parents that their kids could develop a lot of life skills if they would just unplug their maids,” this working mother said. “Like a lot of Hockaday parents, I complain about the amount of homework, but I’m complaining for a different reason. I need her to help with the housework at night.’’

You can’t sit in classes at Hockaday or even walk down the halls — which are filled with art exhibits, interesting book displays, and the sound of a voice student rehearsing her recital in the Great Hall — without worrying that education is wasted on the young. One recent graduate told me that she remembers walking into the building for her admissions interview: “I thought, ‘This is all so fantastic, but I’ll bet someday I take it all for granted.’ And I did.” No matter how splendid the educational atmosphere may be, kids are kids, and their immaturity will always limit what they can absorb. “We always spent more time figuring out how we could sneak out of the symphony performance at McFarlin Auditorium to get ice cream on the SMU drag than we did listening to the symphony,” recalls one graduate of the ’50s.

I sat through an English class in the Upper School, where students were analyzing Hemingway’s story “The Killers.” The insightful reading they had apparently given their homework assignment was remarkable. Another class was reading John Knowles A Separate Peace, a novel with built-in appeal for Hockaday girls since the story deals with a boys’ boarding school. As they read, the students kept critical journals which facilitated reference to imagery and recurring themes. When the class was over, I had to stifle an impulse to shake each little girl and say, “Do you have any idea how lucky you are? You won’t get this sort of teaching and individual attention until you get to graduate school, if then.’’ Few classes in Hockaday’s Upper School exceed 15 students. Some have only nine. You can’t get lost in the crowd.

Some complain, however, that though you may not get lost, you can certainly be overlooked when the awards are handed out. Some kids thrive on the competition and the pressure of such an environment. Miss Hockaday herself was a great believer in pushing girls to achieve their highest potential. But there are so many more distractions today and so many more areas in which girls can achieve. One parent said, “I couldn’t be happier with Hockaday; my only concern is that my daughter feels compelled to be a Renaissance woman, and she may burn out trying to be the best in everything.”

I heard a lot of talk about “burning out” from parents who are concerned about their ambitious daughters. Although some of the girls are quite certain about their chosen careers, there are still plenty of kids who don’t feel entirely secure with the liberation that has been thrust upon them. For some, their primary concern may still be “Somebody show me how to care what men think.” “My daughter tells people she’s going to be a nurse just because she feels she has to have some career plan in mind, but I think all she knows about herself at this point is that she likes to sing,” said one mother. The younger students at Hockaday may not suffer this loss of confidence when they’re seniors because they’ve had a longer time to contemplate the opportunities. I am told that there is a 4-foot-tall seventh-grader at Hockaday who is certain that she will cure cancer. Others in the lower grades speak glibly of spending a few years at Time-Life before launching brilliant literary careers. It makes you wonder who’s going to run the charity balls and TACA auctions of the future.

What would Miss Hockaday have to say about all of this? She might find a lot of it “highly irregular,” but then again, I think she might also see threads of continuity that would be pleasing to her. In addition to the excellent sports training that Hockaday has always given, the school still fosters a love of reading. My contemporaries who graduated from Hockaday in the early ’60s are among the best read women I know, and I think Hockaday had something to do with it. And as any girls’ school must, Hockaday appreciates female wit — particularly wit with some intellectual sophistication. So if these ambitious graduates should opt for the gracious life some of their mothers have led, they won’t be entirely unequipped.

Very little of Hockaday’s finishing school tradition still exists. However, I did sit in on a Form meeting in the Upper School and hear a debate over who should be honored at their tea. Even in 1978, hardly anyone graduates without having properly poured tea at least once during her high school years. And Miss Hockaday’s belief that her girls should be exposed to outstanding personalities continues. In recent years Hockaday girls have talked informally with Gloria Steinem, Nancy Dickerson, Lily Kraus, Nobel prize winner Norman E. Borlaug, and a host of artists, poets, and authors of children’s books. These extraordinary experiences are served up so frequently that I occasionally wonder if life after Hockaday will seem dreadfully dull.

Miss Hockaday would feel completely comfortable with graduation. Except that there is no pergola on the new campus, graduation is unchanged. Lower school girls dressed in white are first in the procession, arranged by class and according to height. Sisters of the graduates still form an honor guard arch of gladiolas through which the entire procession passes. The seniors, wearing long white dresses that have been supplied by Neiman-Marcus since 1916 and broad-brimmed pastel horsehair hats (now purchased at K-Mart if you’re on a tight budget) and carrying wicker baskets of fresh-cut flowers, proceed in measured, much-practiced steps to “Land of Hope and Glory” and take their seats in the bleachers in front of the assembled parents and guests. The speaker this year is Dr. Hanna Holborn Gray, new president of the University of Chicago. Eleanor Roosevelt gave the commencement address in 1952. The student body still sings “O Brother Man” and concludes with a tearful “Taps” as the flag is lowered. In 1970 there was a brief stuggle to include “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” but tradition won out.

Tradition has a strong hold on Hockaday. The alumnae took Miss Hockaday seriously when she wrote: “And my dear ones, I know you will care for and nourish this school of yours and mine through the years to come.” As I wrote this article, people kept insisting that I compare Hockaday with St. Mark’s. One parent summed it up neatly when she admitted that all of the clamoring for Hockaday to be like St. Mark’s was rather like Henry Higgins’ soliloquy from My Fair Lady, “Why can’t a woman be more like a man?” Because of its longer history and because it is in the business of educating girls, Hockaday is a far more complex school. For many of its alumnae, it was not just a school; it was a way of looking at life. “St. Mark’s,” as headmaster Ted Whatley will tell you, “is a Sputnik school pragmatically established by industrialists who were interested in turning out scientists.”

It also occurred to me that men seem to pass through the institutions of their youth – schools, camps, fraternities — and if these are pleasant, worthwhile experiences, they may send occasional checks or letters of recommendation for a friend’s child. Women, on the other hand, tend to be more sentimental about their institutions. Perhaps we also view ourselves as custodians of important traditions that men might ignore. Or perhaps because so few of us pursued careers until recently, we have stronger feelings about our high school and college days as days of important achievement. At any rate, the fact is, women have traditionally had the time to remain involved with their institutions. As one “outsider” put it, “Hockaday seems to be both a victim and a beneficiary of its own success. It graduated all of these intelligent, strong, concerned, opinionated women, and now they return full force with their daughters and all sorts of ideas as to how the school should be run.”

Sometimes the alumnae may be too caught up in preserving the past. One board member recalls making an impassioned plea for the upgrading of the science library at Hockaday. To illustrate his point, he passed out some very dated science books that were still in the Hockaday library. When he sat down, a white-gloved hand went up. “You know, you’re absolutely right about the library, and I think the first thing we should do is get these books of Miss Hockaday’s bound in leather.”

Hockaday will not be able to shake its “rich” reputation because it has very affluent alumnae, who like the school’s founder have an uncompromising demand for quality in their lives — only the best will do. For some, that means being sure that the cafeteria still serves excellent food, or arranging for the Latin Banquet to be held at Brook Hollow. For others, it may mean giving a lovely silver tureen to be used at tea parties or an exquisite rug for a Memorial room. A display case in the hall arranged by alumnae last week featured the 1923 Idlewild Ball gown, slippers, and dance program of dear Miss Louise Kribs, the bookroom bulldog who frightened me so eight years ago. These small cozy gestures seem to say, “You may educate our daughters for the future, but we will not let you forget who you once were.”

But some of the alumnae are concerned with more than the quality of material things that surround Hockaday. These are the women with the liberal arts educations who feel that Hockaday gave them a self-reliance that grew out of knowing some things thoroughly. They worry that as the school has grown, broadened its aims, and offered more options to accommodate more tastes, it is in danger of losing the vision and cohesiveness that it had in the early days. They worry that the school will flounder in trying to be all things to all people. They are skeptical of current trends that say, “Establish your career goals, and we will shape the education for them.”

These are the cross-currents and paradoxes that are Hockaday today. The school is rich and poor; it is new and also old: shiny glass buildings house elegant antique-filled rooms; girls wear streamlined uniforms and carry calculators, but the same girls will also don horsehair hats and pour tea.

Mrs. Lively, the housekeeper, eyes me suspiciously as I have coffee in one of the Memorial rooms with a young staff member. There is a classic standoff here between the generations, and I am in the middle. Like a curator in a museum, Mrs. Lively’s look implies, “This is all we have of her lovely things, and they must be preserved, so drink your coffee elsewhere.” And the younger generation stubbornly ignores her reproving glance and finishes her coffee as if to say, “The past is lovely, but when it ceases to be useful in the present, how can we justify the cost of maintaining it?” I am uncomfortably in between, still pragmatically using Grandmother’s hollow handle knives, but polishing them more often and no longer tossing them in the dish-washer. I think Hockaday is too.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author