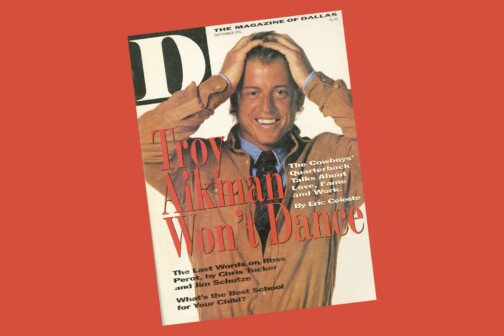

D Magazine’s new editor-in-chief wanted to make a splash in 1992. She wanted a celebrity cover, and the Dallas Cowboys’ dashing new quarterback, Troy Aikman, was her No. 1 pick. While the editorial staff knocked around some possible freelance sportswriters to take on the story, Eric Celeste, a 24-year-old editorial assistant, shook his head. “This is the story I’ve been put here to write,” he said.

Now, an editorial assistant is just a squeak above intern on a magazine’s masthead, and they don’t typically get cover stories, let alone the year’s juiciest assignment. But growing up in Oklahoma, Celeste went to school with one of the top two quarterbacks in the state. The state’s other top quarterback was Aikman. “I was invested,” Celeste says. He told the magazine’s new editor that he would give the story time and energy that no one else would. This was much the same argument he gave Aikman’s team. “I basically challenged him,” Celeste says. “Don’t do this if you just want to half-ass it. I want to actually give a full picture of who you are.”

Over the course of Aikman’s three-month off-season, Celeste met with the athlete on about a dozen occasions, a level of access unimaginable today. Celeste sat in on Aikman’s business meetings, and then they hit up Jason’s Deli. He joined the quarterback at a barbecue that turned into a dance party. (Thus the cover line “Troy Aikman Won’t Dance.”) Sometimes Aikman would pick up the young journalist, and they’d just drive around.

The 8,000-word story was as in-depth and revealing a portrait as one could write of a celebrity who guarded his nice-guy image like Aikman did. Except for one detail.