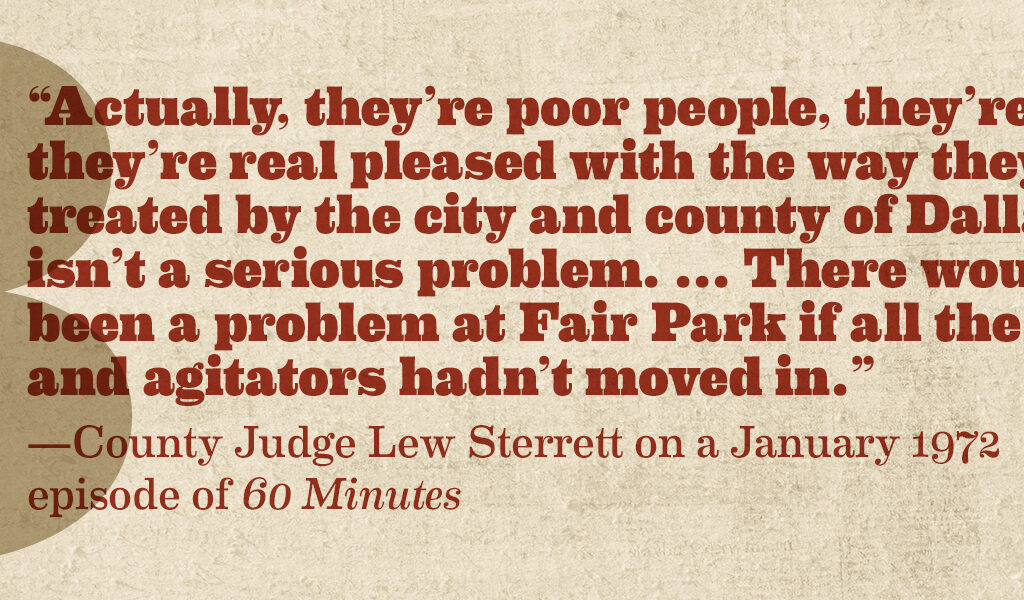

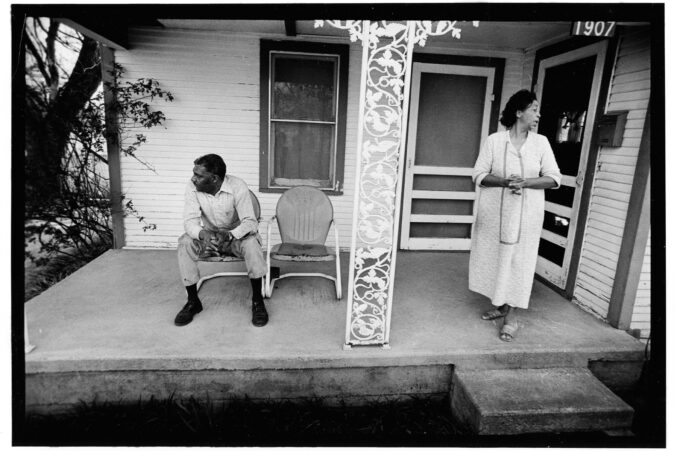

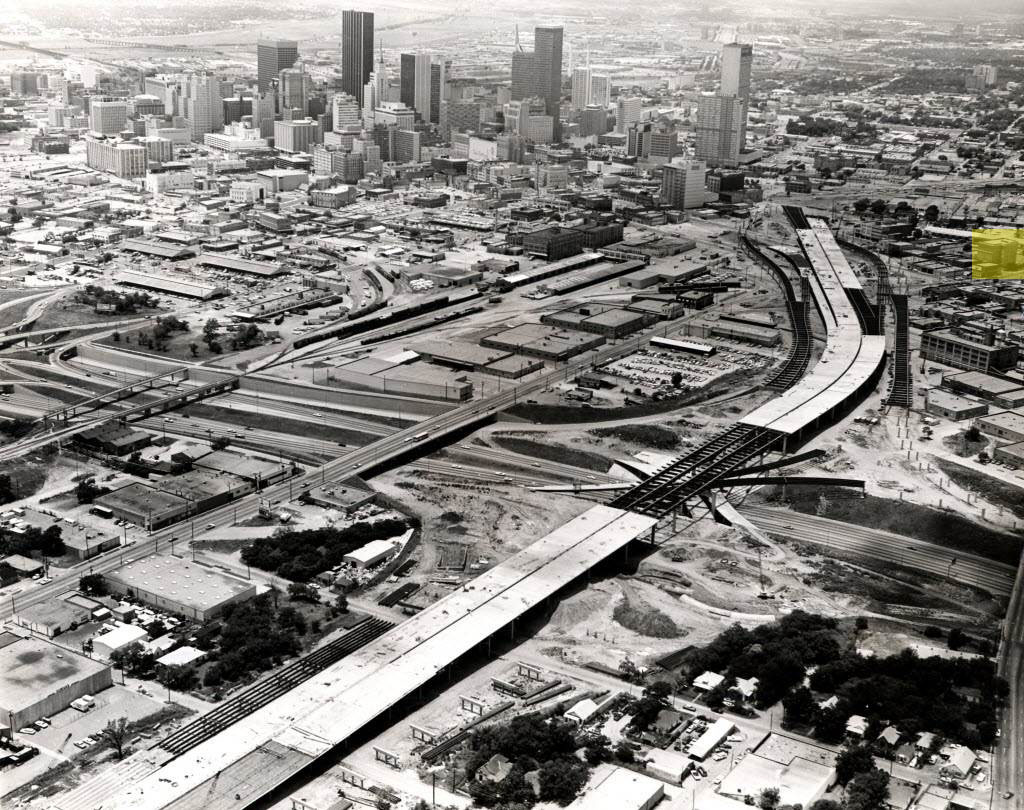

Over the past five decades, D Magazine has covered many chapters of Dallas’ history. In our November issue, we published a story that begins in 1959, when State Fair officials first floated their intentions to eliminate the homes of some 300 Black families so that a parking lot could be built for visitors attending the State Fair of Texas. Three weeks out of the year.

Of course, it was more complicated than that.

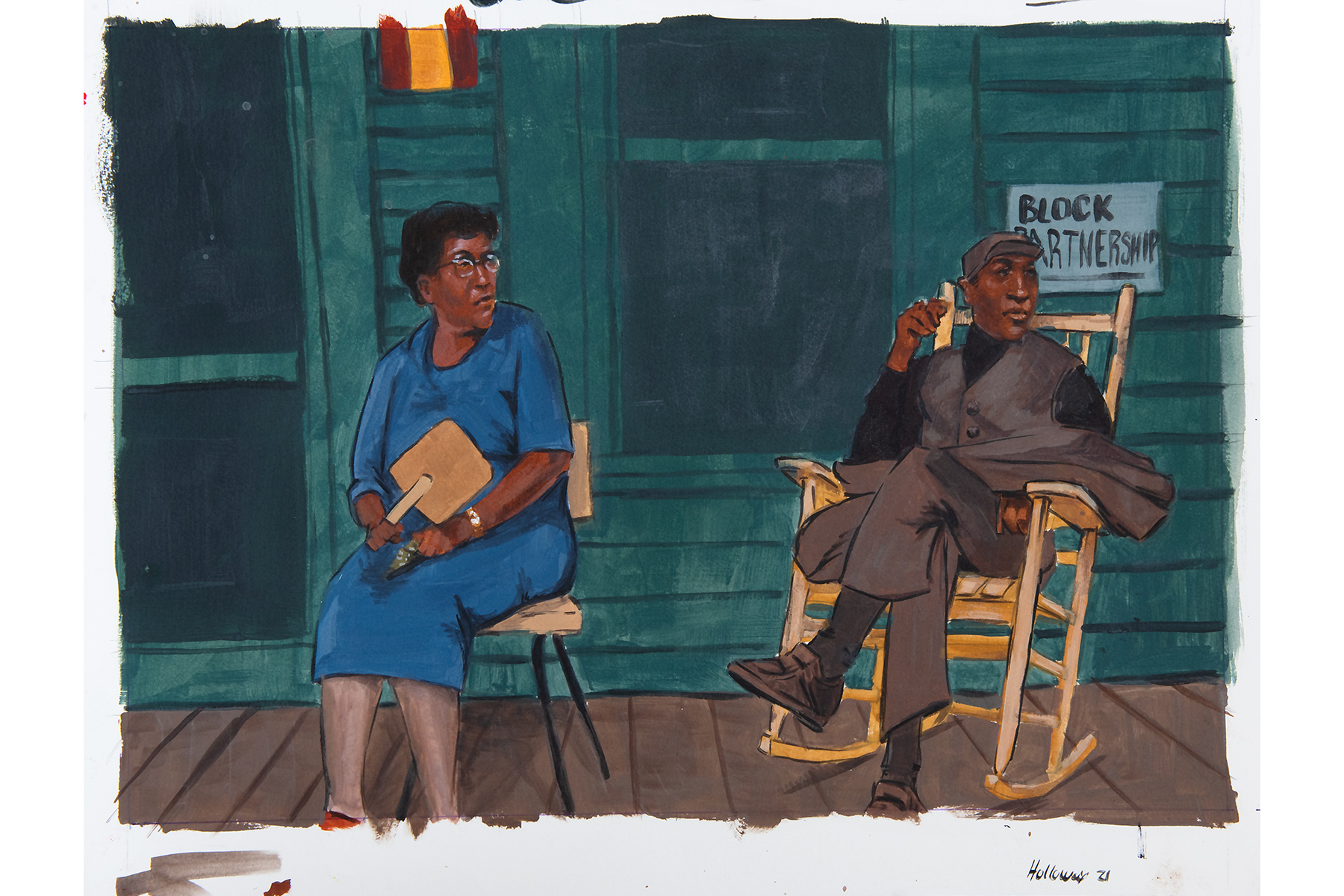

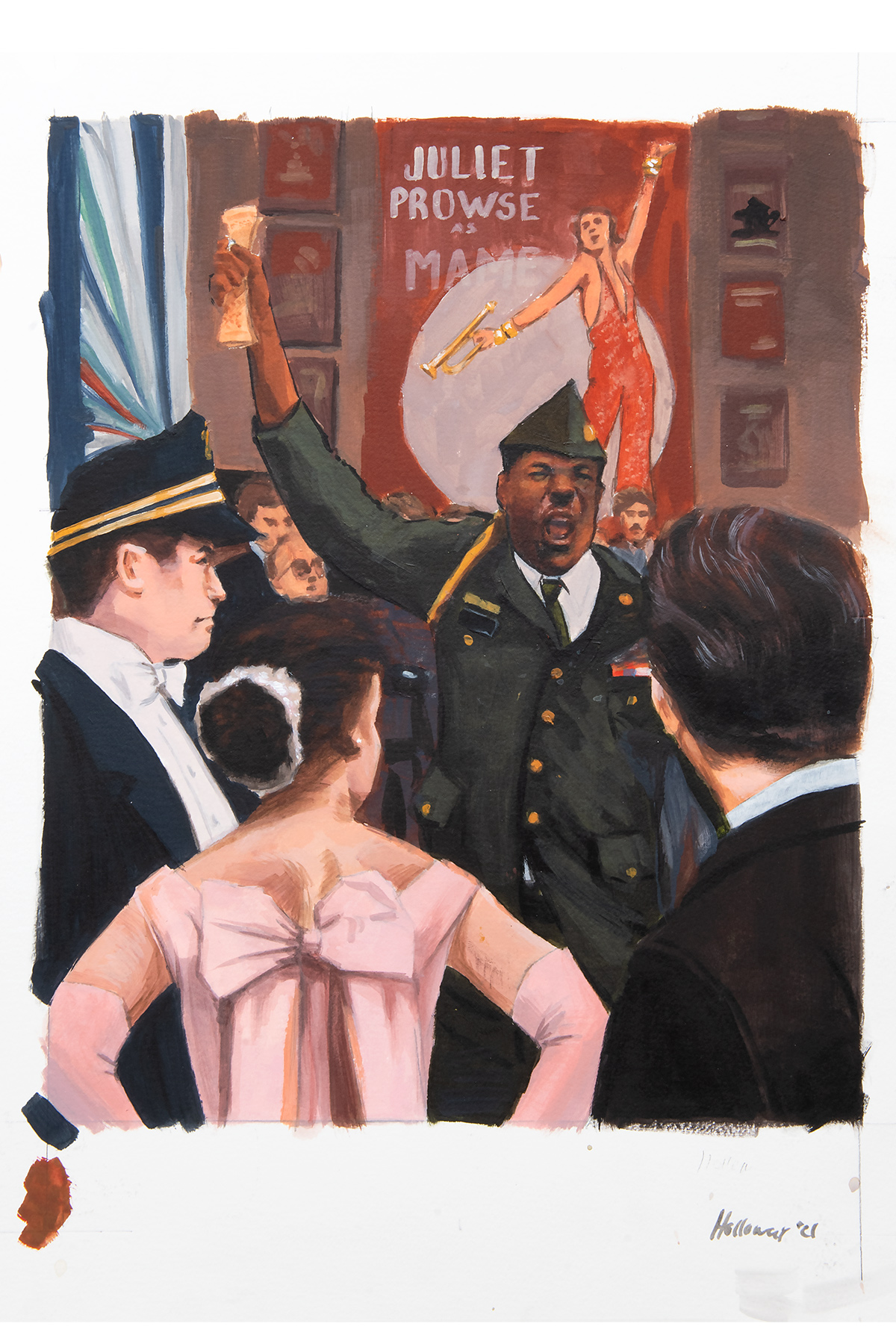

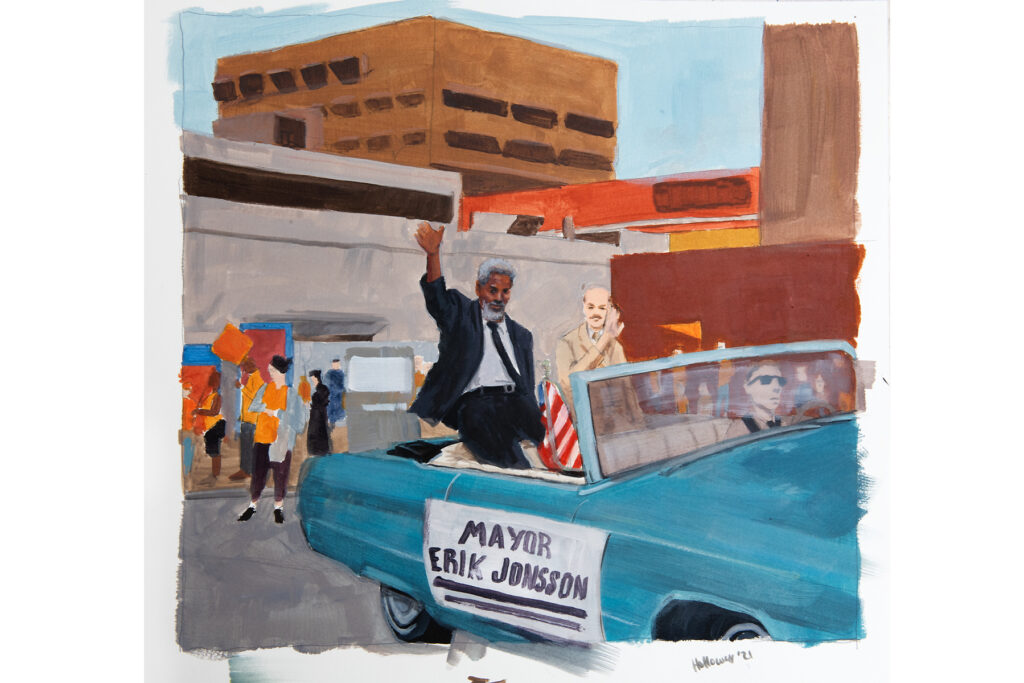

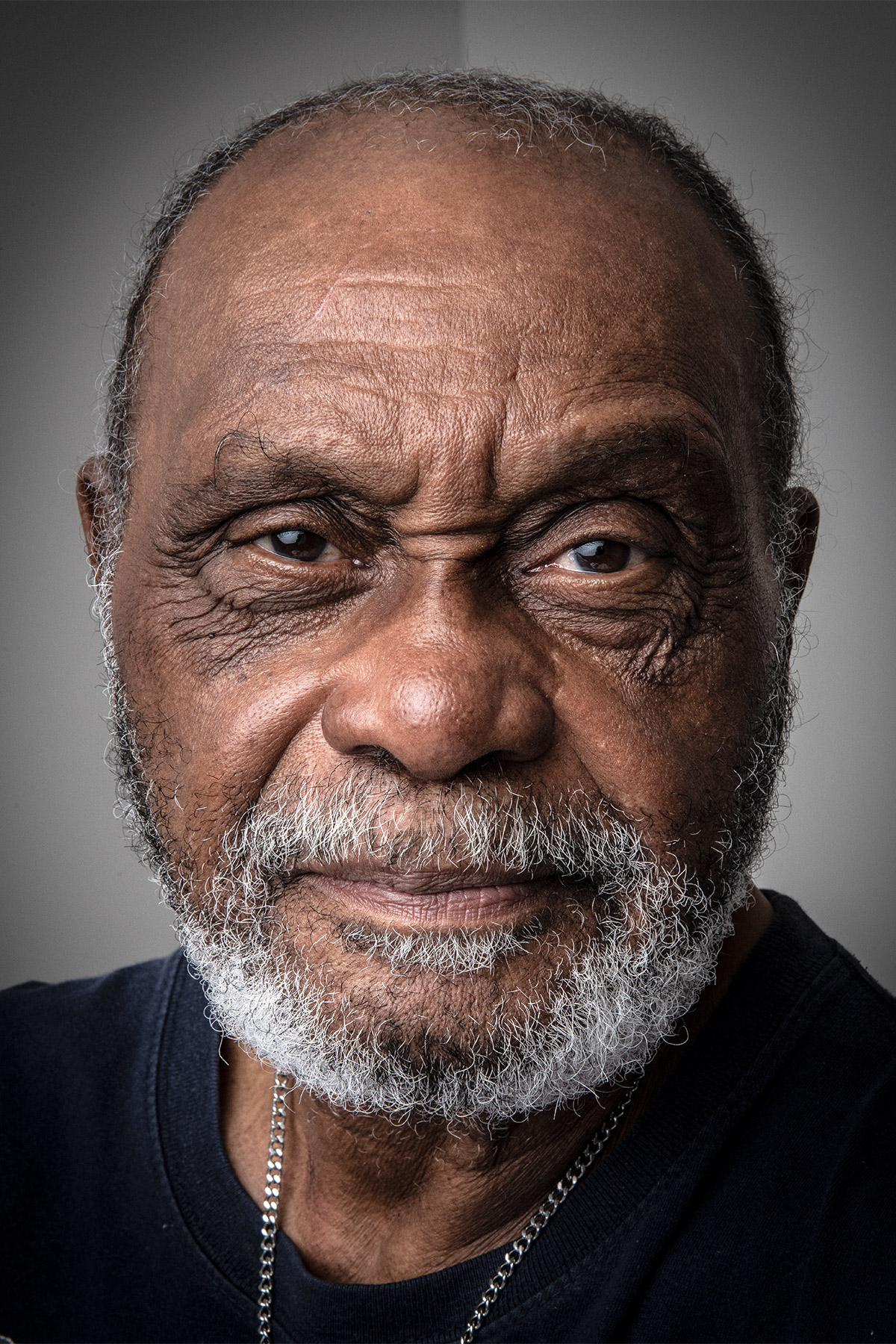

We began working on this story about a year ago, in anticipation of the new Community Park that Fair Park First aims to build on top of that parking lot. Fair Park First, mindful of the history of the displaced Fair Park families, has involved residents of South Dallas neighborhoods to create a space that embodies the community’s highest and best dreams. But before the ribbon is cut, we wanted to document how the Fair Park families who came before them were mercilessly chased off their land. So we could learn. And so the individuals who came to their aid—such as Rev. Peter Johnson of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the late Miriam Schult of the University Park United Methodist Church, and the late Rev. Mark Herbener of Mt. Olive Lutheran Church—will be remembered for their audacity and courage at a pivotal time in our city’s history.

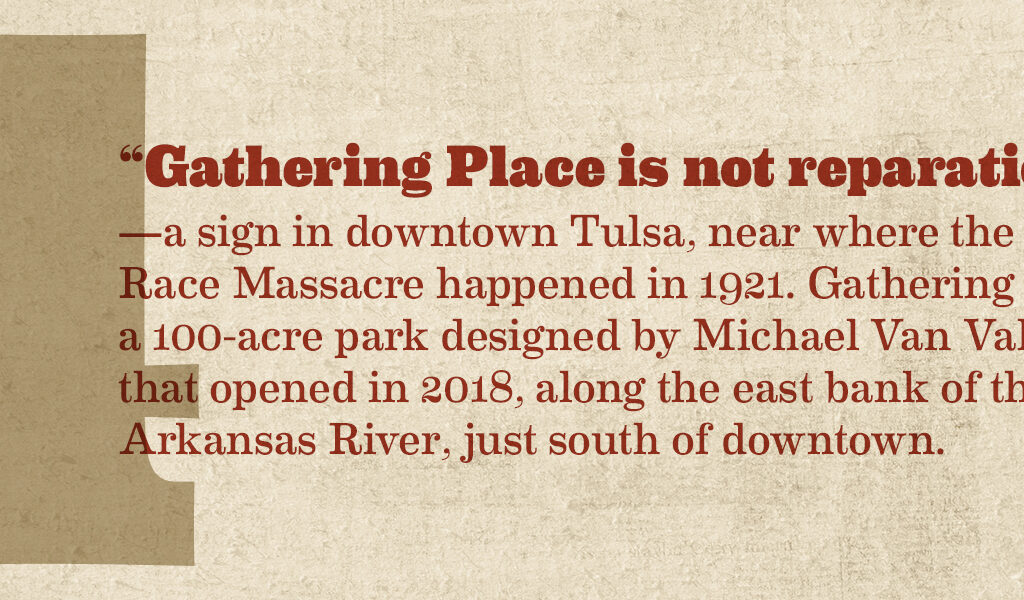

Cities are like families. We tend to bury the bad stuff. No one heals with that approach, and this story is an offering toward that crucial end. This month’s cover story, “The Fair Park Lie,” is online today. It is a microcosm of what happened to Black families in cities all over the United States during the 1960s. It’s a story that needed to be told. May the new Community Park at Fair Park reflect the imagination and remarkable determination that define our city. May it truly and powerfully serve the South Dallas community. And may the descendants of the Fair Park families find peace and equanimity wherever they are.

Thanks for reading—and for helping to make Dallas an even better place to live.