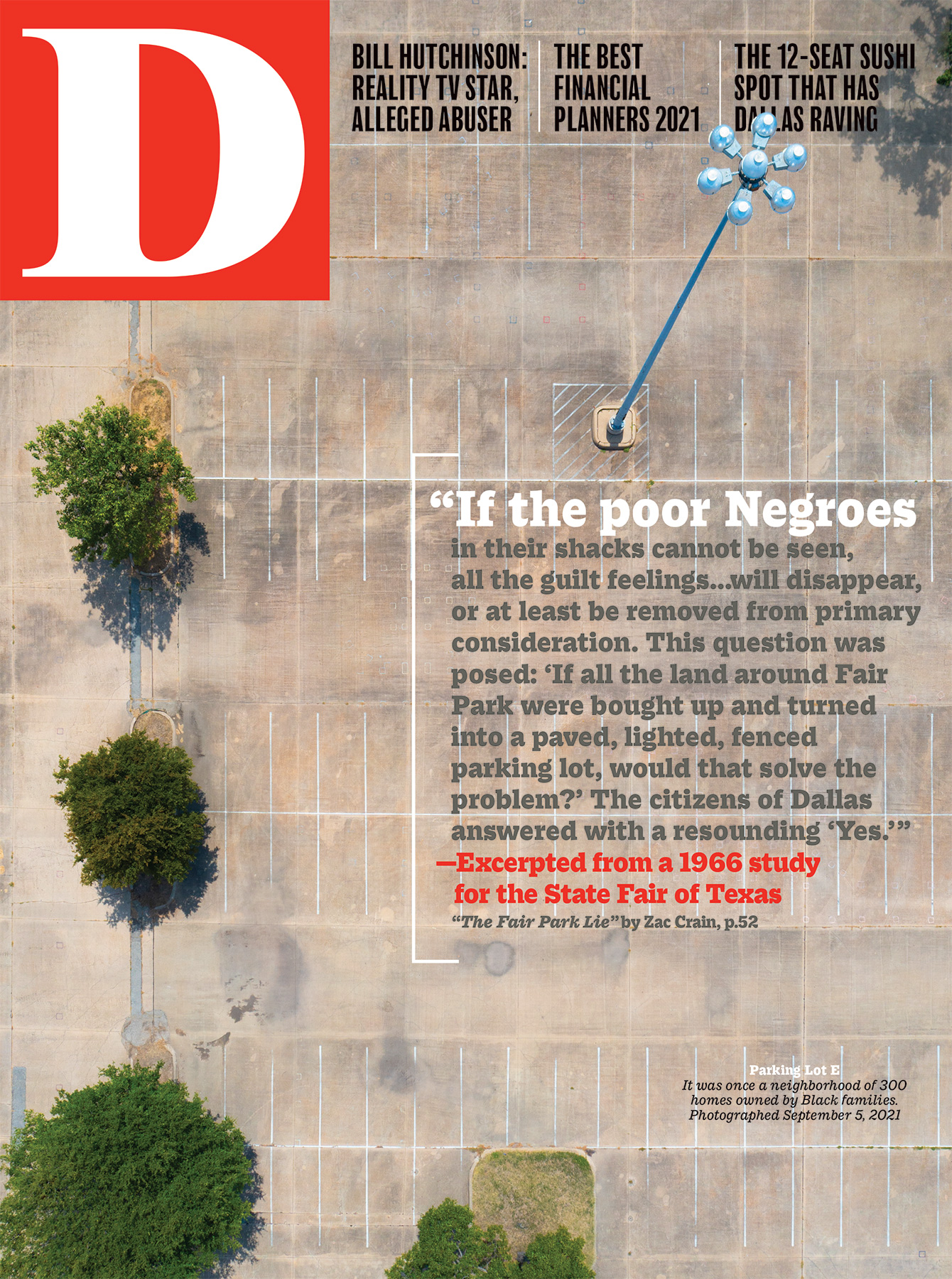

Editor’s Note: This is a companion piece to our November cover story, “The Fair Park Lie.” While the piece below stands alone, it is intended to expand on the themes within the larger story. Read it here.

To get to Music Hall for the performance of Mame that evening in 1970, many patrons would have passed the site where the Hall of Negro Life once stood. It was just 500 feet away. By then, it was a parking lot.

The Hall of Negro Life was built for the Texas Centennial Exposition in 1936, along with the art deco buildings that still line the esplanade. Like them, the hall was designed by famed Dallas architect George L. Dahl. Though the exhibition wasn’t included in the original plans—it was funded by the federal government and practically willed into existence by A. Maceo Smith, the president of the Dallas Negro Chamber of Commerce—the Hall of Negro Life proved to be one of the most popular attractions of the Texas Centennial. It drew more than 400,000 visitors during its run, at least 275,000 of whom were White, as general manager Jesse O. Thomas (of the National Urban League) noted in his 1938 book, Negro Participation in the Texas Centennial Exposition.

“Many of the white people came in expecting to see on display some agricultural products, some canned goods, and ‘Black Mammy’ pictures, as many of them suggested,” Thomas wrote. Instead, guests were greeted by four murals by Harlem Renaissance painter Aaron Douglas and given a copy of W.E.B. DuBois’ pamphlet “What the Negro Has Done for the United States and Texas.” Then they were shown exactly what that meant, with displays celebrating advancements by Black Americans in science and medicine, education, literature, and music.

“They were so shocked with what they saw,” Thomas wrote, “many of them expressed doubt as to the Negroes’ ability to produce the things there on exhibit. All of them went away with a higher appreciation of the Negroes’ contribution to American culture and with a more tolerant attitude toward the Negroes’ effort.”

Despite this, or maybe because of it, the Hall of Negro Life was demolished almost immediately, gone in less than a year, the only one of Dahl’s buildings to suffer that fate. It was replaced by a swimming pool for Whites only; when segregation ended, instead of opening to Black swimmers, it was filled in and became a parking lot, which it remained until the African American Museum opened there in 1993.

Given Fair Park’s tortured history with race, the only surprise is the continued presence of the African American Museum. Fair Park has mostly taken from Black people; it rarely gives back. It has operated that way since the beginning.

The Dallas State Fair & Exposition was chartered in 1886, on 80 acres of what some called “the worst kind of hog wallow,” according to Willis Winters’ 2010 book, Fair Park. Organizers paid $200 per acre for the land, just on the other side of Pennsylvania Avenue, on what would become the back part of the fairgrounds.

The first designated day for Black people to attend the fair came in 1889, dubbed Colored People’s Day. There were speakers—Booker T. Washington was brought in to make an address in 1900—and special events and exhibits. By all accounts, it was a success, at least for what it was. But it was discontinued in 1910.

In the meantime, another group was welcomed: the State Fair of Texas officially designated October 23, 1923, as Ku Klux Klan Day. Dallas Klan No. 66, established in late 1920, had risen to become the largest chapter in the world, according to its members, which eventually numbered 13,000 in a city of scarcely more than 150,000; one in three White men of eligible age was a Klansman. Ku Klux Klan Day brought in 160,000 visitors (one of its highest weekday totals). Twenty-five thousand of them gathered at the football field that night to watch the largest Klan initiation ceremony ever: 5,631 men were added to the ranks, with 800 women joining the auxiliary.

It was the high point for the Klan in Dallas; its membership began to dwindle, along with its local political influence, which was vast in the 1920s. Still, historian Darwin Payne notes that the Klan was able to keep a full-time office near Fair Park as late as 1929.

With the Klan mostly gone again, a day set aside for Black people to attend the fair returned in 1936, now called Negro Achievement Day. It was set up like an entire run of the fair stuffed into one day, with a parade, a pageant to name a queen, an awards ceremony honoring the Most Distinguished Negro Citizen, and football games (high school in the afternoon, college at night).

That didn’t make up for not being able to participate in the fair all those other days. It didn’t make up for what happened at the fair all those other days.

“You had African Americans humiliated routinely at Fair Park,” the historian and author Michael Phillips (White Metropolis: Race, Ethnicity, and Religion in Dallas, 1841–2001) told a group at a town hall meeting in 2016. “There was a dunking booth where an African American would be sat in a chair. You hit the target and he would be dumped to the water. And this is actually the slogan on the sides: ‘Hit the trigger, dump the Negro.’ ”

The NAACP Youth Council, under the leadership of Juanita Craft, staged a boycott of Negro Achievement Day in 1955, picketing with signs like “Don’t sell your pride for a segregated ride!” By lunchtime, the protest had drawn attention from media across the country.

“Why would I come here for this day and give every penny that I have to this concern who won’t let me come back tomorrow?” Craft said later.

By 1957, the event had become known simply as Achievement Day; by 1961, it was removed from the schedule entirely. As a policy, segregation at the fair had ended. Officially, at any rate. By 1970, Fair Park had only been fully integrated for about three years, and, in fact, many said discrimination lingered around a couple of Midway rides until just the year before.