Last summer, Monty Bennett—Dallasite; wealthy Trump donor; founder and CEO of Ashford Inc., a publicly traded company that, with its associated real estate investment trusts, controls about 114 hotels—found himself cast as the poster child of corporate greed. An investigation into recipients of the federal government’s Paycheck Protection Program revealed that his organization had received more than $69 million in forgivable loans, the largest known recipient of such funds intended for small businesses. The federal agency overseeing PPP changed its qualifications for receiving aid, and even though Bennett’s companies had done nothing wrong, they returned the money. In a Dallas Morning News article, he blamed the whole kerfuffle on the media.

Then, in October, Bennett was back in the national spotlight when the New York Times published a story about an alleged nationwide pay-to-play fake-journalism network involving hundreds of small, local outlets. The Times reported that Bennett had ordered numerous articles to be published, some lobbying for the stimulus bill and others laying out his thoughts on Chinese foreign policy. When I wrote on D Magazine’s FrontBurner blog about that Times story, Bennett lashed out on Dallas City Wire, a local site that is part of that fake journalism network, falsely claiming that D Magazine engages in pay-to-play journalism and opining that the magazine had “deteriorated” since the death, in 2020, of its publisher and founder, Wick Allison, who had been a friend of Bennett’s.

Bennett in a few months’ time decided to ditch the middleman and become publisher of an online news operation called the Dallas Express. “There are many publications in our wonderful city, but none we can count on daily to present just the facts,” Bennett wrote in a publisher’s note that first appeared in February but has since been updated. “I can’t take it anymore—and I know many of you can’t either.”

But Bennett’s Dallas Express dabbles in more than facts, which is what you might expect from a publisher who is combative, unapologetic, and fiercely libertarian. It publishes a mix of right-leaning opinion pieces, excitable crime reporting, and regurgitated press releases. Its editorial stance is laid out in a list of principles that reads like Heritage Foundation talking points (“government spends rather than invests,” one reads). But it isn’t the content of Bennett’s local media experiment—or his irascibility—that rattles. Rather, it’s his choice of name.

The Dallas Express was a weekly newspaper that published from 1892 until the mid-1970s. It was one of the longest continuously published Black-focused newspapers in the country, and, at its height, it claimed to be the highest-circulated such newspaper in the South. With offices located in the heart of Deep Ellum, it was founded at a time when the Black community in deeply segregated Dallas was ignored by the rest of the city. Dallas’ mainstream newspapers did not report on the issues, people, and events important to many Black readers. So the community had to report on itself. Too often, that meant printing stories about everyday discrimination and shocking brutality. The paper once published a first-person story by a Black man named Willie McNeeley who’d been castrated by a mob of White men in a small East Texas town called Pittsburg.

Dallas itself was effectively run by the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. The Express was often the only newspaper reporting on the lynchings and terroristic attacks used to keep Black communities in line. It wrote about the 1919 murder of Bragg Williams, who was dragged out of a Hillsboro jail by an “orderly mob” and burned at the stake. That same year, the paper covered the so-called Great Battle of Longview that broke out between White and Black residents of the East Texas town after a Black man was lynched for being inside a White man’s house. The paper also reported on bombings aimed at Black families moving into White neighborhoods in North and South Dallas throughout the 1920s. These incidents showed how Dallas’ segregation laws, as an Express editorial put it at the time, were “more than just on the books.”

The Express’ editorial page advocated for improvements to segregated schools and anti-lynching laws that never passed. In 1921, the Ku Klux Klan sent a letter to the paper trying to shut it up. The Klan called Dallas “white man’s country,” insulted Express editors with racial slurs, and accused them of being “enemies of poor ignerent [sic] Negroes trying to incite them to Rebellion.” The Express published the letter, along with an editorial response: “We are not agitators,” the paper said. “But we do stand by the truth as we see it and protest against injustice … .”

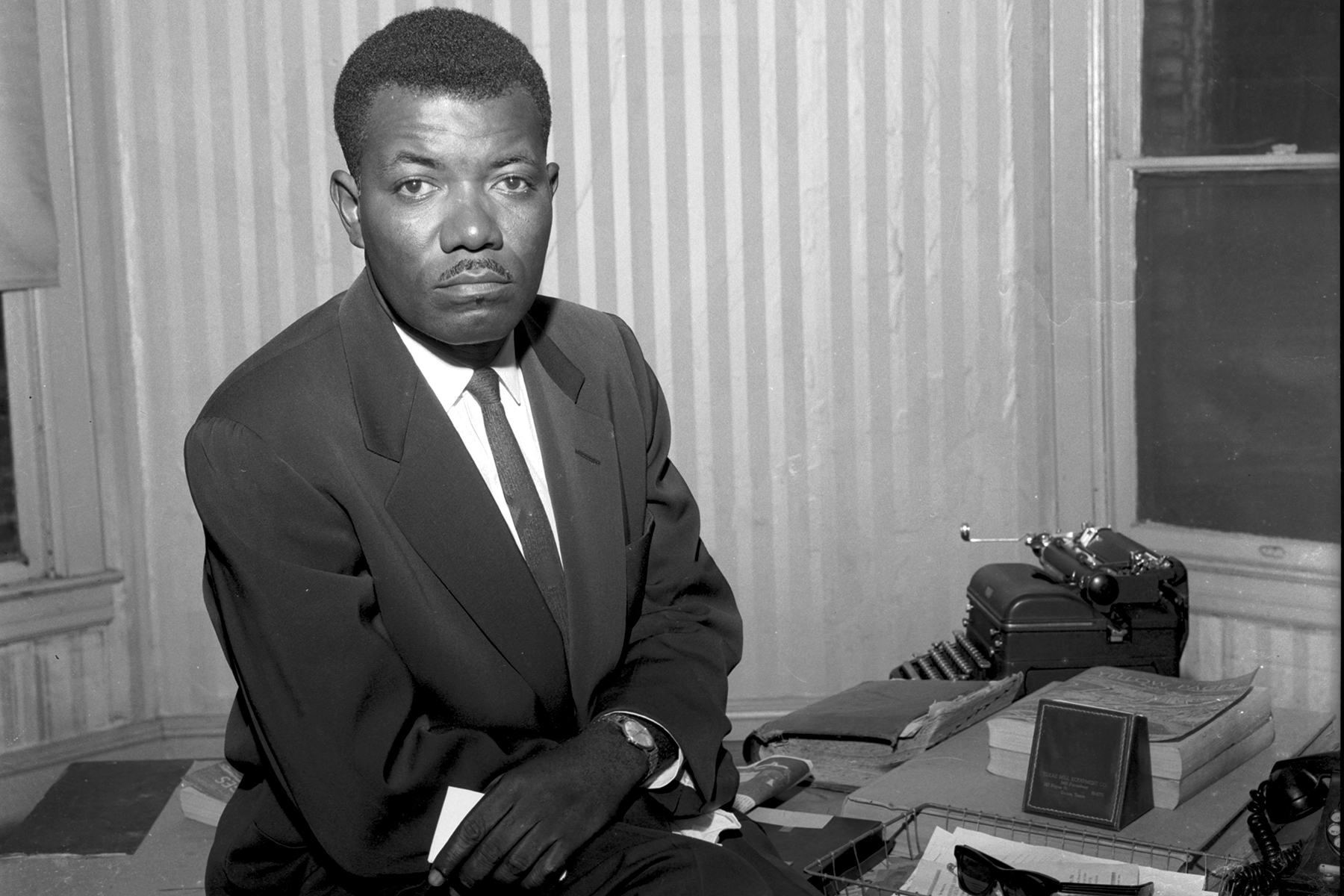

The bravery of the people behind that editorial cannot be overstated. This was a time when Black men and women were being lynched, as the paper reported, for crimes ranging from “making boastful remarks” to “discussing a lynching.” The Express survived the KKK, but financial troubles took a toll. In 1930, amidst declining subscriptions and sales, the paper was purchased by a White businessman named Travis Campbell. In 1938, a partnership of Black leaders organized to buy back the paper. In 1940, it was acquired by Carter Wesley, a Black Houston-based lawyer and activist who would shape the paper’s tone through the postwar period.

Wesley’s Express warned readers about the rise of Hitler. In 1948, he traveled with 10 other publishers of Black-focused newspapers to report on discrimination against Black troops stationed in Germany. The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s slowly began to improve some social and economic conditions for the Black community in Dallas, and the Express reported on marches and lunch counter sit-ins taking place throughout the South. But progress on civil rights also ended the segregation that, paradoxically, had given rise to the Black press. Sociologist and author E. Franklin Frazier wrote about this phenomenon in his 1957 book, Black Bourgeoisie, in which he explained how the very existence of the Black press reflected the disenfranchisement of its readership.

“One of the most striking indications of the unreality of the social world which the black bourgeoisie created is its faith in the importance of the ‘Negro Business,’ i.e. the business enterprises owned by Negroes catering to Negro customers,” Frazier wrote. “Faith in this social myth and others is perpetuated by the Negro newspapers, which represent the largest and most successful business enterprises established by Negroes.”

Frazier unveils a complex contradiction: the Express was both a fierce advocate for the Black community and symptomatic of its oppression. The pages of old editions display this uncomfortable reality. Ads for hair and beauty products tout remedies for lightening skin. Sensationalist crime reports repeat stereotypical narratives. A huge ad in a 1960 edition promotes the Sonya Wilde film I Passed for White, about a young, mixed-race woman who marries a White man and is afraid that their child will out her race. In the 1920s, one editorial in the Express celebrated when a Black man was convicted of rape, because at least he had received a trial.

As the civil rights movement made progress, the Express struggled to hold an audience. Darryl Blair Sr., publishing editor of Dallas’ Elite News, says many Black community newspapers here survived by focusing on niche audiences. His father, William Blair, who founded the Elite News in the 1940s as a Southwest sports newsletter, turned his focus to the church community. “I do recall him talking about the Dallas Express, and it did give lifeblood to the Elite News,” Blair says. “He found a niche because the Dallas Express existed. We would be a church community publication where we would keep the narrative out there for the churches.”

The Express may not have been able to evolve with shifting social circumstances, but there is no denying the vital role it played. The Express discussed local political issues through the lens of Black experience, publishing stories about public transit and the hiring of Black police officers. During the 1936 Texas Centennial, it advocated for the construction of the Hall of Negro Life. It organized voting blocs to leverage support for city council candidates who promised to improve schools and housing. It also published news about church gatherings, social organizations, and new business openings.

Those reports make archived editions fascinating historical documents. (You can see a few examples by clicking through the gallery attached to this story.) They describe a world that is still mostly overlooked by historians and scholars, and they show us how much of this city’s complicated past remains unexamined. Blair admits that even in the Black community there is not much awareness about the Express, which is why he is concerned about the co-option of the name for a new website.

“That seems a bit disingenuous,” Blair says. “What is the purpose of pulling up a historically Black publication that was the cornerstone of our publications? Is it to inject a narrative through our community subliminally through one of our publications?”

Perhaps Bennett believes his site somehow pays homage to the original Dallas Express by giving voice to what is, in his mind, a marginalized perspective. Maybe he’s not even aware of the historical significance of the name. I don’t know. After I submitted questions for Bennett to an Ashford representative, I never heard back. Instead, Bennett’s lawyer contacted the law firm that represents D Magazine. Regardless of Bennett’s motives or the journalistic integrity of his project, it’s impossible to imagine how the new Dallas Express can achieve anything other than further obscurity of the newspaper’s legacy.

“That’s my concern,” Blair says. “Do what you want with your money. Everyone is entitled to your opinion, and, more importantly, they’re entitled to the facts. I’m not opposed to anyone starting a publication. What I am opposed to is someone wanting to change the narrative.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author