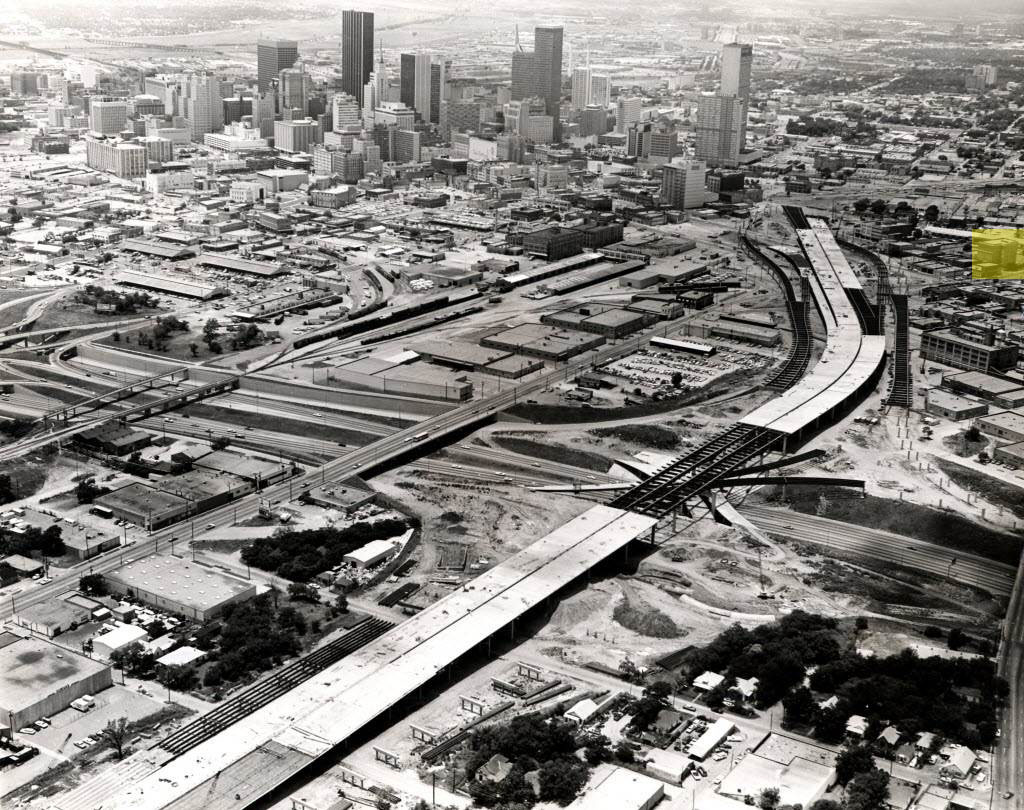

Last month, the Texas Department of Transportation unveiled initial designs for replacing or removing I-345. TxDOT included five possible options for the future of the road that cuts through Deep Ellum and which, as we have argued for a number of years, should ultimately be torn down. They include:

- Doing nothing

- Rebuilding the existing road

- Replacing I-345 with a trenched highway

- Removing the highway altogether

- A “hybrid” option that includes some removal and some trenching

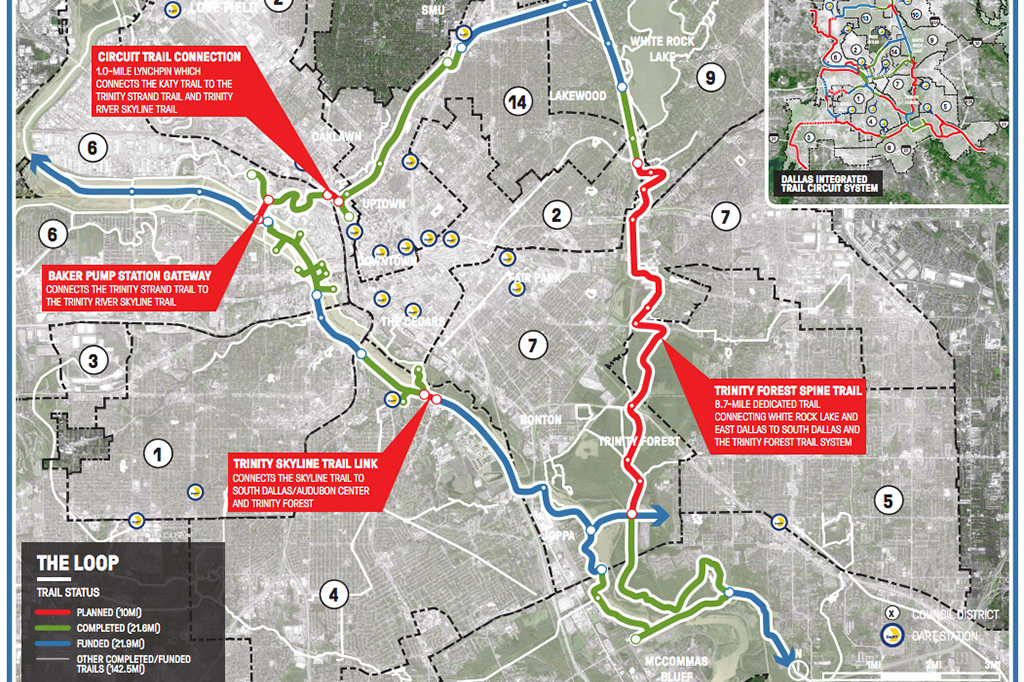

Last Thursday, the Coalition for a New Dallas hosted a conversation with renowned urban planner Peter Park to discuss the options. (Full Disclosure: The Coalition was founded by D Magazine’s late founder Wick Allison.) Park’s takeaway: the designs aren’t there yet. In fact, Park even found TxDOT’s design for I-345’s removal to be lacking and said that none of the early plans for the future of I-345 fully maximized the full potential of what a reimagined I-345 could mean for Dallas.

“I think you can do better,” Park told moderator Patrick Kennedy, who started this whole I-345 teardown business.