We’ve been publishing D Magazine since 1974. Over the years, we’ve had women on many of our covers. Models, for the most part. Airbrushed. One wearing nothing but whipped cream in a visual reference to a vintage Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass album cover. (Clever!) Lots of blondes. LeAnn Rimes. Jessica Simpson. We did feature the Honorable Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison on our July 1995 cover, but her face was photoshopped onto a model in a red-white-and-blue bikini. She’s a media pro and laughed it off. (Still.)

As a business unit, these covers were about newsstand sales and merchandising. But they also suggest that we’ve not always taken the women in our city seriously. We’ve improved over the past few years, but, just like Dallas, we have a ways to go. I credit our entire editorial staff for seeing beyond the stale paradigm of Dallas as owned and operated by a nameable male few and instead filling our pages and website and events with a full range of complicated, brilliant, surprising, and remarkable individuals from every part of the city, men and women.

What makes our previous casting of women even more wrongheaded—beyond the outright objectification—is that, on a local basis, it was a false projection. There is nothing and no one more powerful than a Texas woman. I know. Years ago, when we moved our four daughters down from New York, I worried I would have to blow-dry their hair and take them shopping all the time. I wondered who their role models would be. But what I discovered were my own role models with every new acquaintance. My friends are bold, hilarious, audacious forces of nature. Whether they were driving carpool or block-walking for candidates or running Fortune 500 companies, these women showed me what it is to be strong and resilient. Raising our daughters in Texas was the greatest gift my husband and I could have given them.

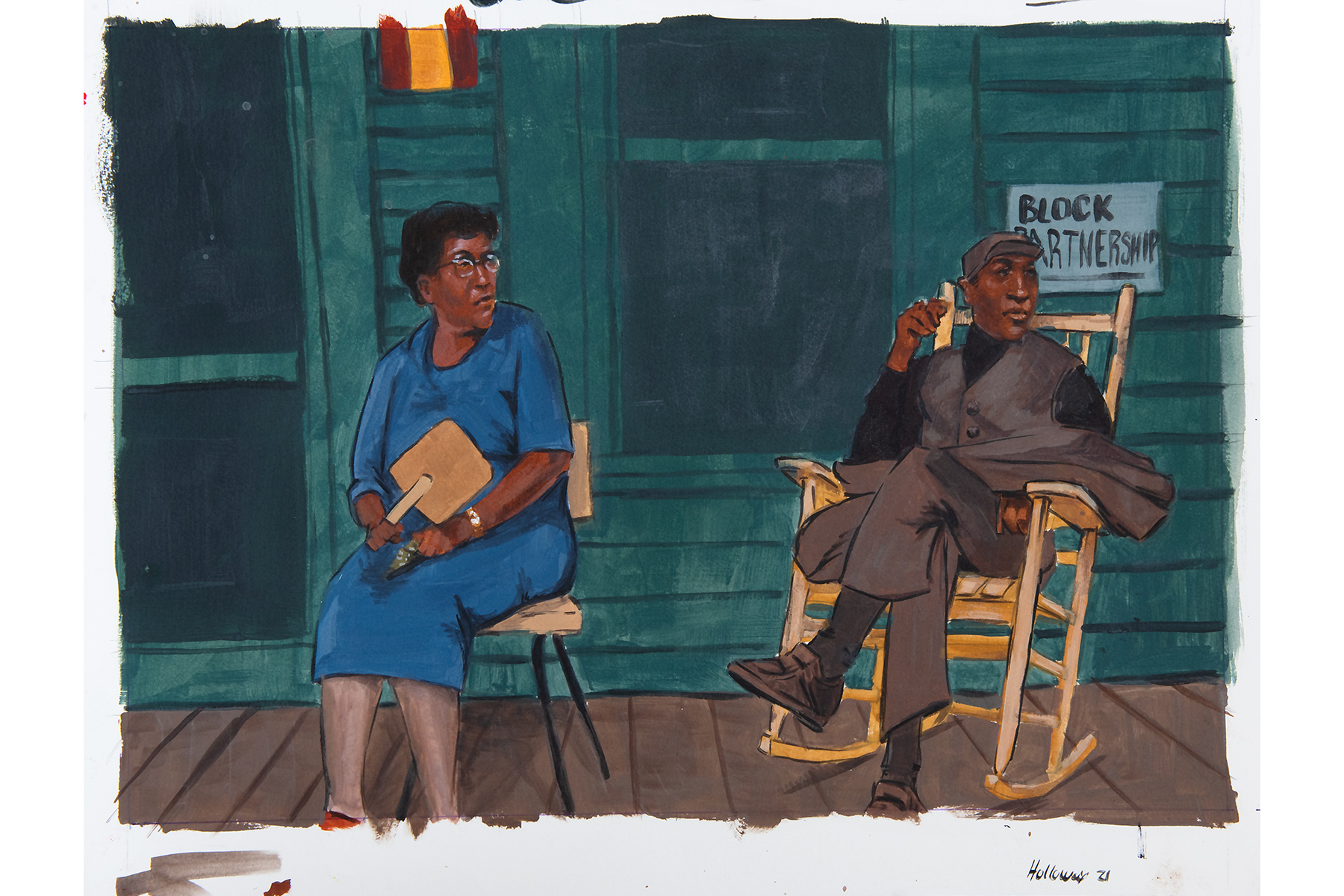

Last September, we presented 78 local giants, legends, and emerging leaders, who are but a sampling of the hundreds of thousands of women who have made Dallas the city that it is today. We held off publication until our new website went live, so that it would benefit from its new design capabilities.

To honor Women’s History Month, which began today, we’re proud to finally put the feature online. You can read it here.

Had we the pages, we could have filled volumes with the names and achievements of the women who create and fund our cultural institutions; innovate in technology; fight for social justice; create new businesses; break athletic barriers; establish our aesthetic standards; teach and advocate for our children; rescue and harbor those in need; lead our churches, temples, and synagogues; toil in the civic arena; revolutionize healthcare and research; and stir the soul and conscience of a city all too often concerned only with appearances and wealth.

I hope you enjoy meeting them.

Of course, this story didn’t just happen. The final product was made possible by the efforts of members of every division in our company, the majority of whom are female. I adore our team (our guys are the best, truly). But it is the women who inspire me every day. This issue is dedicated to them.