This is my last post.

After 12 years with D Magazine, I am leaving the publication for a new opportunity (more on that in a second). Over the years, when I imagined leaving D, I thought the last thing I would write would be a sweeping review that summed up everything I had learned during my years here—thoughts and reflections on the state of the city, where it is today and how much it has changed and stayed the same.

Over the past couple of weeks, I’ve written a few versions of that post. None of them felt right.

What I really want to write about in this last post is Julien Reverchon, the 19th-century French botanist who has a street and a park named after him. During the early days of the pandemic lockdown, as we all huddled in our homes experimenting with new hobbies, I began to research Reverchon’s life and work. I had recently moved into a house a stone’s throw from where Reverchon’s farm once stood, near the corner of Davis Street and Plymouth Road in Oak Cliff.

A creek runs along the back edge of my property. As I took my quarantine walks each morning, I imagined that Reverchon must have wandered up and down it, perhaps even stopping under the 150-year-old burr oak in my backyard to stare at the babbling creek and wonder how his life’s journey had landed him in Dallas.

Reverchon came in 1856 to Dallas against his will. He traveled here at 19 with his father, Maximilian, who fought in the failed 1848 revolution. After Napoleon III seized power, Maximilian decided to try his luck with a fledgling Fourierist colony in Texas called La Reunion. Julian’s mother and brother stayed behind in France, and when the father and son arrived, the socialist experiment was already beginning to fail.

The Reverchons claimed a parcel of land within the colony as far from the main La Reunion settlement as possible. Reverchon’s mother, who inspired Julien’s love for botany during countryside walks around Lyon, never joined her husband in Texas. Maximilian died in 1879. Julien married Marie Henri, another La Reunion outcast who was the granddaughter of a solider who had fought with Napoleon at Waterloo. They had two sons who died of typhoid fever in 1884, leaving the French botanist to the solitary life of a frontier farmer.

“Julien Reverchon did not appear to be deeply affected by his marriage,” Samuel Wood Geiser remarks dryly in his book Naturalists of the Frontier. “His interest in nature gradually took the place of almost all others.”

That would have been the end of the story, but in 1869, a Swiss naturalist named Jacob Boll arrived in town. Boll was commissioned by Harvard University to survey the Texas frontier for new plant and animal species. It was the age of scientific adventuring, and professor-explorers scoured the earth—often hand in hand with military forces—cataloging all the wondrous things that lay beyond the European horizon.

Boll collected butterflies and reptiles and is credited with first finding Texas’ dinosaur fossils. One of his patrons was Asa Gray, the great American botanist and friend of Charles Darwin. Gray sent emissaries throughout the American frontier and amassed one of the greatest collections of plant specimens in North America, still housed in the Harvard University Herbaria.

When Boll arrived in Dallas, he was told he should seek out the quirky, lanky Frenchman who lived on the other side of the river and seemed to know something about plants. Boll hit the jackpot. Reverchon had spent considerable time wandering the Dallas countryside and observing the things that grew there.

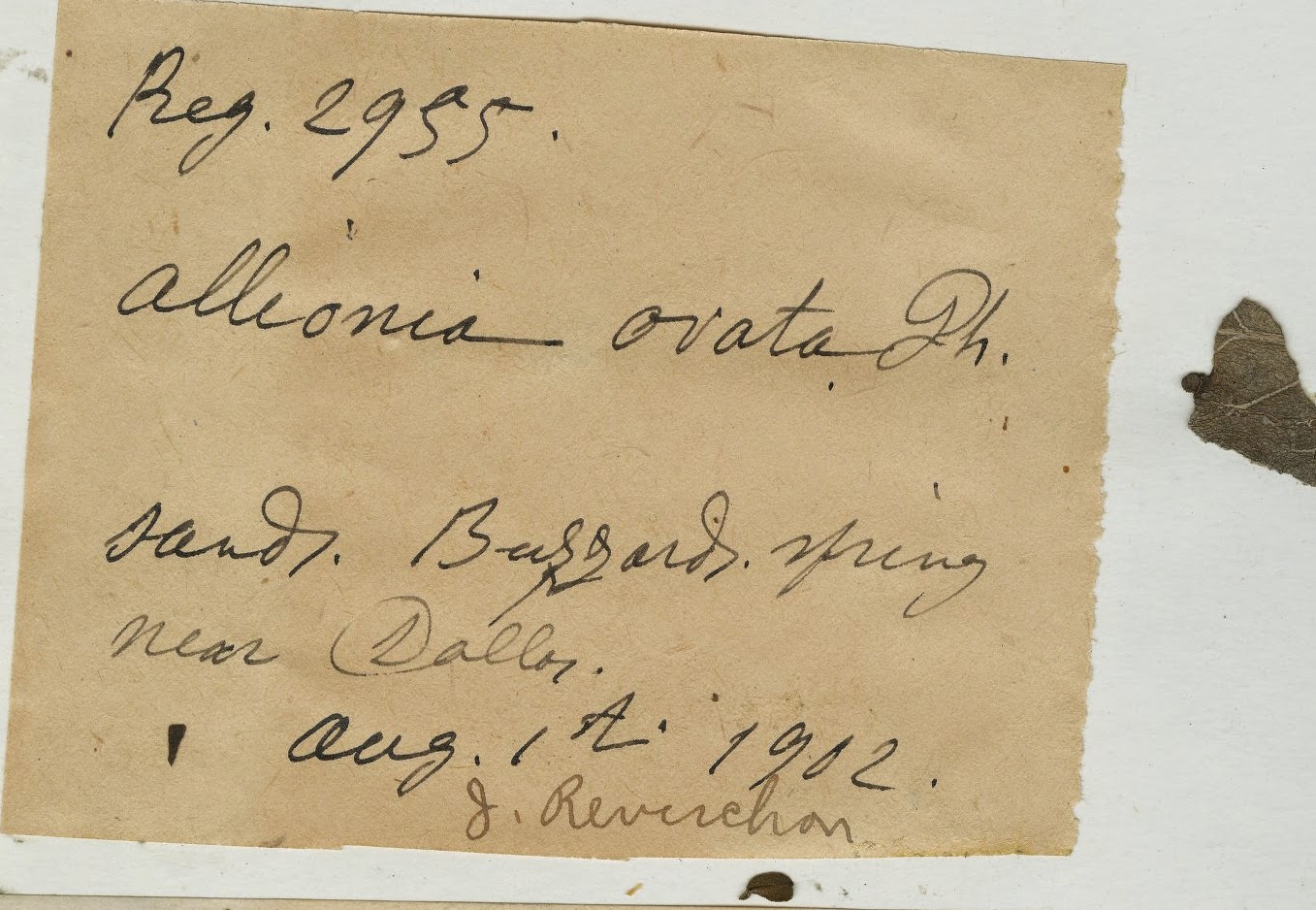

After meeting Boll, Reverchon’s passion found purpose. For the remaining years of his life, Reverchon embarked on numerous expeditions, both around Dallas and throughout Texas, collecting specimens, pressing them, and sending them back to Asa Gray, with whom he established a lively correspondence. On a small, sandy island in the middle of the Brazos River, near the town of Seymour, Reverchon found a plant—a member of the Phyllanthaceae family—that neither he nor Gray had ever seen. Like its discoverer, its branches were long and lanky and decorated with thin, spindly leaves.

Gray affectionately named it Reverchonia.

I spent many hours during the early days of the COVID lockdown reading Reverchon’s letters to Gray, which are now digitized in the Harvard archive. I’m not sure why I was so enthralled by this obscure 19th-century scientist, but something about Reverchon’s story moved me. I wanted to write about it, but I wasn’t sure how.

I reached out to Ben Sandifer, who, unsurprisingly, already knew more about Reverchon than I had learned and had even gone so far as to reconstruct some of Reverchon’s nature walks through Dallas. I thought I might write about Reverchon’s life through Ben’s eyes, uniting these two unsung champions of Dallas’ overlooked and oft-disparaged natural beauty who were connected through a century of footsteps.

I had some other, wilder ideas. I began to wonder if the affection shared between Reverchon and Boll went beyond fauna. I imagined scripting a historical drama that cast a lonely French farmer and a dazzling Swiss adventurer as unrequited lovers who allowed themselves a fleeting moment of social transgression in the unseen shadows of a Texas farmhouse.

I considered taking up botany myself and even purchased a plant press online that still sits in a closet unused. The idea was to collect and study specimens along my little stretch of Reverchon’s creek and use that information to “re-wild” my backyard in honor of the late Kevin Sloan. If Dallas’ rich and powerful wouldn’t let its nature enthusiasts restore the Trinity River floodplain’s natural ecosystem, at least I could restore my postage stamp of Trinity River watershed.

I also read more about the history of 19th-century science and natural philosophy and learned how Reverchon’s story snaked through broader narratives of American expansion, exceptionalism, and colonialism. Science and politics have long been uneasy bedfellows. The new knowledge of the 19th century was used to justify war, oppression, injustice, and genocide. It felt like a prescient story, as the psychological and economic pressures of the COVID-19 lockdown boiled over into street protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in the summer of 2020.

In the end, all this research didn’t manifest anything concrete. That has happened a lot of late. Ever since the start of the pandemic writing for D has become more of a struggle. But learning about Reverchon did affect me in another way. I began to see something of my own Dallas experience in Reverchon’s life.

I have spent more than a decade at D Magazine, occupying my little corner parcel in this city’s public discourse. I have had the privilege to wander this city with open eyes and report back what I saw. But the longer I sat with Reverchon, the less I felt compelled to write about him, and the more I started to feel like—and this is the part that I can’t quite articulate without sounding corny—he was my Jacob Boll.

Reverchon’s story was saying to me, “Get up, get going.”

We are living through what has been dubbed the Great Resignation. I’m joining it. I am leaving D Magazine to join EarthX, the Dallas-based environmental expo-turned-television network. The role will challenge me to help advance its environmental advocacy, grow its public profile, expand its reach, and refine its voice.

I’ll be wearing a few different hats, and I encourage you to follow me on Twitter to stay up to date on what’s next. I’ll still be writing a lot, telling stories, and also working alongside EarthX’s great staff in an effort to resolve what I believe is the most profound and consequential issue of our age: the struggle to create a more sustainable and viable world. In other words, I’ll be able to think about plants and things all of the time.

Writing about Dallas has been rewarding beyond words, and I thank you, dear FrontBurnervians, for your support, engagement, insight, feedback, criticism, and patience over the years. I am also grateful for D’s support and the long leash the magazine has given me.

I joined the magazine in 2010 by launching what was then a rather unruly little arts page. D let me hire brilliant, iconoclastic talents like Christopher Mosley, host public screenings of Rainer Werner Fassbinder films, and invite bands to perform in the office on Friday afternoons to drown out the week’s last sales calls. Later on, D allowed me to opine freely on a range of topics of which I had no formal base of knowledge or authority but let me leap in headfirst nonetheless.

When I say D, I especially mean Wick Allison. Wick cheered me on when I hurled rocks at politicians and philanthropists and argued for crazy things like tearing down highways and blowing up the Trinity River Corridor Project. Even when we didn’t see eye to eye, Wick let me run loose. It helped that Wick was on board with a lot of these crazy ideas, and nothing has been more thrilling about this gig than working with him to help move these ideas into the mainstream.

We lost Wick during the pandemic. Another blow.

If I had to end my time with the magazine with a grand, sweeping statement about Dallas, I would say this: in a certain sense, Dallas hasn’t changed all that much since Reverchon’s day. The people who leaven this city’s cultural and civic life still tend to reside on the outskirts. The city’s brightest lights are often its most peculiar and misunderstood residents. One great part of my job at D is that I had the perfect excuse to head to the fringes and seek out the many wonderful misfits—people like Ben Sandifer and Kevin Sloan and so many others—that make Dallas a rich city, often despite itself.

Because here’s the thing. After wrestling with Dallas, criticizing and defending it, I have come to terms with the fact that, in many ways, Dallas is its stereotype. Dallas is the money-worshipping land of big egos and big hair (seriously, let’s admit it, there’s some weird hair in this town). It’s the hometown of malicious, hypocritical W.A. Criswells and charming and conniving J.R. Ewings. Dallas is insecure, tacky, and perpetually adolescent. It tends to compensate for its inferiority complex by spending money on big, shiny things.

Jimmie Dale Gilmore still said it best when he sang that “Dallas is a rich man who tends to believe in his own lies.” It’s what makes the city so much fun to write about.

But Dallas is also home to many Julien Reverchons and Jacob Bolls, people who toil away on the cultural and social peripheries and breathe real life into this city. Because they often find themselves working against a dominant culture that doesn’t see or understand them, they are strengthened, refined, and made more resilient by it.

They are the ones who wage Dallas’ great civic battles—the greatest of which, more often than not, are those fought over the smallest things. Because, despite Dallas’ booster propaganda, it’s the little things—not the big things—that make cities great. And it is through the fight for seemingly inconsequential things such as decent sidewalks, dignified housing, equitable transit, and accessible spaces to perform or create that Dallas might realize its ambition of being considered “world class.”

Which brings me to the sad, if fitting, end to the Julien Reverchon story. Reverchon dedicated the last years of his life to the little things, painstakingly collecting and gathering plant specimens throughout the region, which he cataloged in a botanical study of Dallas. You can find Reverchon’s handwritten lists of plants in the Harvard archives, and they read like inventories of army battalions—non-native species organizing ranks against the besieged native flora. Even in Reverchon’s day, North Texas’ native ecology, which had existed undisturbed for thousands of years, was fading away.

By the end of Reverchon’s life, his collection consisted of some 20,000 plant specimens—likely the largest and most significant herbarium in the Southwest. When he died, in 1905, a small community of admirers looked for somewhere to house the collection.

No one in Dallas was interested. In the end, they found an institution that agreed to preserve Julien Reverchon’s life work. Today you can visit it at the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author