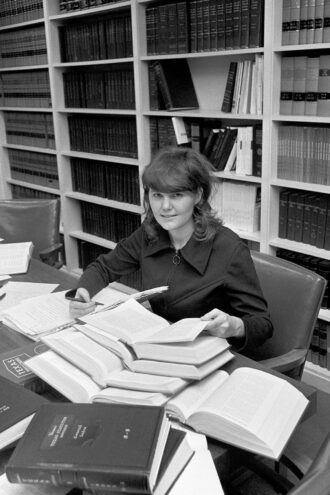

Linda Nellene Coffee was born in Houston on Christmas Day in 1942. After a younger sister was born, the family of four moved to Dallas. There, every Sunday, they prayed at the large Southern Baptist church on Gaston Avenue, where Linda’s grandfather was a deacon.

The church was a hearth, home to more than prayer. It was where little Linda went for Sunday school and softball and choir, an alto in a dress.

Coffee liked the organ; in time, Bach would give her goosebumps. But after watching the band at Stonewall Jackson Elementary march into the school auditorium, she chose at age 9 to play the clarinet.

The second-grader’s first choice had been drums. “Something real physical and fun,” says Coffee. Dad had said no. But he said yes to softball; he coached the team. And so, his firstborn played shortstop and then catcher, crouching in mask and Jerry Coleman glove, writing her address in black marker on the back of its pocket: 5711 Anita.

Home on her lawny lane in suburban Dallas, Mary Coffee was too nervous and displeased to watch her daughter play; a girl ought not to squat. The housewife had long envisaged a daughter more like her—neat and conservative and feminine. Mary prettied her house and was at the beauty parlor every week. But her daughter hated housework almost as much as the bonnets her mom had once made her wear. The girl was not girly.

Coffee instead resembled her father, a quiet engineer. She was shy but unafraid; she walked on stilts and killed the scorpion that scared the other girls at Baptist camp. She was absentminded but cerebral. Come high school, she joined the Latin and science clubs, tutored math, and took college-level physics. The teachers at Woodrow Wilson High told the Coffees how smart she was. They had but one lament. Says Coffee: “I needed to participate more in class.”

The Family Roe: An American Story

by Joshua Prager

W. W. Norton & Company Inc.

655 Pages

Coffee did not want to. She knew the answers. And she was happy to keep to herself; save Smokey her dog, she had few friends, went on few dates. “When I had to call up some guy to go to a dance or something, it was just awful,” she says. “I hated it!” The teenager preferred to play ball or clarinet, she says—“to do something fun instead of just being a pretty object.”

Coffee was pretty—thin with high cheekbones, her brown hair in a soft bob. She was also “pretty chaste,” she says. After reading a book in high school about a young woman who chooses to have an abortion, it struck her as important for “women to control their fertility.” She wondered why it was acceptable for a man, but not a woman, to have sex before marriage.

Coffee had not yet had a boyfriend when she began her junior year. Her mother was upset and let her know it. “I was beginning to think that our house was too small,” says Coffee. “I needed to be gone.” Coffee was 17 when, in 1960, she left on a student exchange program, bound by steamship from San Francisco to New Zealand.

The students, 28 teens selected by the American Field Service, were meant to represent the United States, and among the items that Coffee, the lone Southerner, presented to her hosts was a Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalogue and a Confederate flag. But her nine months abroad opened her eyes to new points of view; Labour governments, she decided, were not all bad. And when in 1961 Coffee enrolled at Rice University, she peered down career paths that her mother—housewife, census taker, secretary—had not taken, like math and medicine and German literature, Coffee studying the last, one summer in Tuebingen, Germany, on a Ford Foundation grant.

None of those careers, however, seemed a good fit. Coffee found the slide rule in calculus cumbersome. Medical school was too expensive and took too many years. And though Coffee loved Goethe and Mann, she hated Kafka and Schiller. Even secretarial work seemed a stretch, she says, after she “failed a typing test miserably.” By graduation, the only job she’d had was as a carhop at Prince of Hamburgers. Mother was displeased. Says Coffee: “I sort of did it to spite her.”

As a last resort, Coffee took the LSAT. High-minded yet practical, she found that the law suited her, and she began to study it at the University of Texas at Austin. Coffee had joined the Human Rights Research Council, a national organization of law students devoted to “the protection of individual and civil liberties,” when, in 1967, she graduated with high honors.

Coffee thought she might go into domestic relations law; she’d interned at a legal aid society in Austin, helping disadvantaged women to get out from bad marriages. But in 1968, few law firms hired women; a woman needed the backing of a man just to rent an apartment. Not one firm made Coffee an offer. She went to work at the Texas -Legislative Council, paid $600 a month to help legislators draft statutes. She found the work boring.

It was then that her mother heard through a lawyer at the Baptist General Convention that Sarah Hughes, the first female federal judge in Texas, wished to hire another clerk.

Hughes was famous for having sworn in President Lyndon Johnson aboard Air Force One. But long before Kennedy was assassinated, Hughes had been known for her feminism—fighting to secure women equal pay and the right to serve on a jury. When Coffee applied for the clerkship and the judge phoned to invite her to the courthouse for an interview, Coffee was overwhelmed. “My voice,” she says, “was shaking.”

Coffee had little need to worry. The Dallas Morning News happened to print the bar results the April morning of her interview, and Hughes let Coffee know that she’d seen her score—87, second highest in the state. The interview went well until the judge asked her would-be clerk which presidential candidate she wished to see elected. Coffee answered Hubert Humphrey but added that Nelson Rockefeller would be fine. “Her tone changed,” says Coffee. “She said she was not interested hiring anyone who didn’t vote Democratic.” Coffee made clear that she understood that politics mattered: “I said, ‘Oh yes!’ ” She got the job and was soon making her way through a backlog of civil motions.

Hughes appreciated Coffee; the judge told her clerk, Coffee says, that her work “was most satisfactory.” Still, Hughes expected more. Law school had taught Coffee to argue both sides of a case; Hughes wished her clerks to take stances. The judge aspired to legal progress commensurate with the seriousness of the times, and in 1968, America was convulsing—Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy assassinated, the Democratic National Convention shadowed by violent protest.

Coffee was stirred. But as her clerkship wound down, she again saw, as after law school, all the good jobs going to men. “ ‘Oh, we’d only hire a woman for [debt] collection,’ ” Coffee recalls the firms telling her. “ ‘We’d never hire a woman to be a partner.’ ” She adds: “Just overt discrimination. … I was panicked.”

In April 1969, Coffee’s clerkship was winding down when Henry McCluskey visited her at her desk in the jury room of the federal courthouse.

The two had met years before as young classmates in Sunday school at the church on Gaston. The boy was tall and kind, like all his family, a gentle Baptist. And like Coffee, he kept to himself. “We didn’t have to have friends,” says his older sister Barbara, “because we had each other.”

Like Coffee, too, the young McCluskey was taken with music and sport; he arrived in junior high playing bass fiddle and rooting for the Cowboys. Still, the two had not been in touch since high school when, these many years later, McCluskey reached out. He had heard that Coffee was a lawyer in Dallas just like him, and Coffee assumed, she says, “that he was hoping that I could help him. I obviously knew certain things having worked for a federal judge.”

On this spring day, however, it was McCluskey who tried to help Coffee. She said she needed a job, and he suggested that she buy the law practice of a woman he knew who was getting married. The practice, though, was nothing but collections and defaults, while Coffee—who thought she might want to become a prosecutor—hoped to get a job with the Dallas district attorney, Henry Wade. Says Coffee: “I wanted to get experience trying cases.” She had applied for a job with the DA when McCluskey invited her to dinner with his parents and a friend who knew Wade. The friend liked Coffee, and spoke to Wade about her. The DA then interviewed Coffee and told her that she’d impressed him, too. But the only job he had for a woman, he said, was collecting child support from delinquent dads. Coffee turned it down. She had landed at a small bankruptcy firm in Dallas when McCluskey asked her to help him defend a defrauded man. She did so. He then asked for help on a very different matter.

Sodomy was illegal in Texas. It had been since 1860, the Texas General Laws criminalizing sex that might not result in pregnancy—anal sex, and sex between man or woman and beast. The law became binding in 1879. Ninety years later, McCluskey wished to fight it, and had put an ad in a local gay newspaper seeking a plaintiff. He had found one—a man twice convicted of having consensual oral sex with another man. But McCluskey needed help with his suit.

The case concerned matters of privacy, the fact that police spied on locations where men met for sex. “You have the government in the bedroom,” says Coffee. “I thought, that’s awful! That’s just horrible! They would just sit there watching people using the bathrooms!” Coffee was keen to help her friend. Says Coffee: “I wrote some kind of brief and drafted a complaint for him.”

The suit, Buchanan v. Batchelor, did not mention her name. “I wasn’t about to touch that publicly,” says Coffee. “I would not have enough nerve to even be the counsel of record.”

McCluskey filed suit in May 1969 and appeared before the three-judge federal court in Dallas to argue it.

McCluskey had graduated from Baylor magna cum laude and had been the case notes editor of the Baylor Law Review. But he failed to impress, and a law clerk named Randy Shreve, who knew that Coffee was helping McCluskey, phoned her. “The clerk was desperate,” she recalls with a laugh. “He couldn’t understand what [McCluskey] was saying … what his argument was.” The court asked McCluskey for a brief after his oral argument. Coffee wrote the brief and gave it to the clerk, who gave it to the court, which eventually ruled that, as Coffee suggested, the law was unconstitutional at least with respect to married couples. Says Coffee: “I analyzed it right.”

The work on privacy gratified Coffee in a way that bankruptcy did not. She helped McCluskey over and over again that summer of 1969, a Cyrano content to go unrecognized. The lawyers, meantime, got along well. They had much in common, both 26 and single and living with their parents. They began seeing each other outside of work, McCluskey taking Coffee out on what seemed like dates—to the bar at the Adolphus Hotel, to his high school reunion. Their relationship, says Coffee, was soon “somewhere between friendly and more than that.”

That both lawyers were gay went unspoken. But, says Coffee, McCluskey started taking her to places that might communicate what he dared not to—a club for swingers, a gay club for men, a street corner where he alerted her to a man who, he said, was “hustling.” Still, she says, “it seemed that he wanted a straight life.” She adds: “He was having gender—some sort of confusion.”

If Coffee was closeted, she was not confused. She’d upended stereotype from the start, preferring drums to clarinet, math to typing, comfort to fashion, work to the prospect of a family. She’d never had a boyfriend, and retained, she would soon tell a reporter, “a live and let live attitude about marriage.” She added that “we [working women] would like to try it but we just don’t have time for everything at once.”

September 1969 had arrived when Coffee came upon mention, in the SMU library, of People v. Belous, a case that only days before had exonerated a California doctor for referring a woman to an illegal abortion provider. Coffee’s mind raced. Here was a ruling that rendered a state abortion law void on grounds that it was constitutionally vague, that it violated the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Surely the abortion law in Texas was vulnerable, too. “I just thought, My goodness!” recalls Coffee. “The same logic would apply!”

The thought had not occurred to Coffee before. But suddenly it consumed her, the idea, as she later explained, that “process” aside, laws that deprive a person of “some important fundamental liberty”—such as privacy—are in and of themselves impermissible.

Coffee was a feminist, a member of Women for Change and the National Organization for Women and the Women’s Equity Action League. Long mindful that birth control was unreliable at best, and that the illegality of abortion, says Coffee, “seemed to be something that held women back from achieving their full potential,” she now saw that the Texas law enforcing that illegality was weak—a legal relic out of step with the fact, she says, that “if a woman self-aborted, she was guilty of no crime, not even a misdemeanor.”

In a few days, the abortion rights lawyer Roy Lucas would file in New York the first suit against a state abortion law. Coffee told McCluskey over lunch at the Adolphus that she wished to do the same. There was, she said, just one problem: “I couldn’t figure out how I could find a pregnant woman who was willing to come forward.”

Four months later, in January 1970, McCluskey phoned Coffee with word of a woman who’d come to his office wanting an abortion.

It was still January when Norma McCorvey and McCluskey met Coffee downtown in her office at Palmer, Palmer & Burke, where, for $450 a month, Coffee waded through petitions for bankruptcy.

Coffee was intense, incapable of small talk, pale and unkempt besides. All at once, Norma was ill at ease beside her. She looked, said Norma, “like she got out of bed and forgot to comb her hair.”

Looking back at Norma, Coffee saw a small woman with a big belly. Says Coffee: “She looked really pregnant.”

Exactly how far along Norma was could not be known. In 1970, gestational age could only be estimated, and estimates could be off by up to four weeks. “We weren’t using ultrasound at that time,” explains Frank Bradley, the Dallas obstetrician who delivered Norma’s second child. Instead, he says, doctors used pelvic exams and menstrual history to “try to figure it out best they could.”

It was more than likely that Norma had reached at least her twentieth week. And she had thus reached the legal limit at which any doctor in the United States—even where abortion was legal—could perform an elective abortion. In January 1970, abortion was legal only in Oregon, where residents were permitted to abort through the first 150 days, and in California, where nonresidents, too, could abort through 20 weeks. Abortion was also not illegal in the District of Columbia. (A federal district court had recently declared the anti-abortion law in D.C. -unconstitutional, and the appellee in that case performed abortions until at least the 20th week.)

Coffee thus knew that it was almost certainly too late for Norma to get an abortion. “It was my opinion,” the lawyer soon recalled, “that, very likely, the suit would not solve her immediate problem.” It was not too late, however, for Norma to file suit. Indeed, it would be of no legal consequence if the suit Norma filed came to term after she did. “There were fairly established principles that that doesn’t moot the case,” says Coffee. (Among them was the category of cases deemed “capable of repetition yet evading review”—which meant, in essence, that the issue was a recurring one, but in each instance would pass before the courts had time to fully address it.)

It was more than likely that Norma had reached at least her 20th week. And she had thus reached the legal limit at which any doctor in the United States—even where abortion was legal—could perform an elective abortion.

Coffee told Norma what she knew. “I remember saying,” she recalls, “that I thought she was probably too far along to have an abortion under the protection of the federal court.” But Norma had nowhere else to turn. Coffee was her last hope.

Coffee told Norma that if she filed suit, she might have to testify. Norma agreed—never mind, says Coffee, that she “likely had no idea what that would entail.” Coffee sensed that Norma had little idea what filing suit even meant. “I could tell she didn’t have a lot of education,” says Coffee. “Maybe she was being a little too cooperative. … Most people would ask more questions if they were thinking about filing a lawsuit over something of that magnitude.” Norma only asked if filing suit would cost her money. It would not; Coffee would do the case pro bono. Norma agreed to file and left.

Coffee marveled. McCluskey had come through. She had a plaintiff. And that plaintiff was perfect. As Coffee later told a reporter: “It had to be a pregnant woman wanting to get an abortion. She couldn’t have the funds to travel to California … for a legal abortion. And we had to have someone who could take the publicity. We weren’t able to guarantee her anonymity.”

Still, Coffee would try to keep Norma anonymous. Alone in her office, she fashioned for her would-be plaintiff a pseudonym, combining Jane, which was suitably common, she says, with Roe, which was standard legal vernacular and already the surname of two plaintiffs (alongside two Hoes, two Poes, and a Doe) in a 1959 lawsuit on contraception. “In my mind,” says Coffee, “I considered her being Jane Roe as soon as I got an actual woman being ready to file.”

Coffee picked up the phone. There was one person she wanted to alert at once.

Coffee had studied law at the University of Texas alongside a woman named Sarah Ragle. The women were not friends, Coffee says. But they were two of just five women in the entering class of 1965, and both had thrived in law school only to be rejected by every firm.

Both women had since found their footing. Ragle had been hired by one of her professors to help draft the ethical standards of the American Bar Association. But misogyny remained rooted in Texas and beyond. And in the fall of 1968, a group of women in Austin, some 20 current and former students at UT, began meeting to discuss the issues they faced.

Among these was abortion. The women began referring women wanting abortions to those few clinicians they deemed safe. But the women were circumnavigating the law. And in November 1969, they approached a young lawyer they knew—the former Sarah Ragle, who had since married a law student named Ron Weddington. As the author David Garrow later phrased their question: “Would open and aboveboard provision of referral information leave the project volunteers vulnerable to arrest?”

Weddington seemed an odd person to ask. That she was smart was undeniable; she’d skipped two grades, graduated college magna cum laude besides. “I have received very few B’s in my whole life,” she later recalled. But at 24 years old, Weddington was hardly countercultural. She was the daughter of a Methodist minister, had headed her high school chapter of the Future Homemakers of America, and had been assistant house mother for her Delta Gamma sorority. She was middle-class and married.

Weddington, though, fervently believed in the need for abortion reform. Unbeknownst to the group, she had found herself pregnant the year before she was to marry and had traveled to a clinic south of the border in a town called Piedras Negras to have an abortion.

Prim in her ponytail and pantsuits, Weddington had kept her abortion secret. But when approached by the group of UT alumnae, she agreed to investigate their question at no cost. And in late November, she let the women know that she had found no clear answer; the law was ambiguous. The group then wondered if the Texas abortion law could be challenged in federal court. Weddington thought so. Asked if she might file suit, Weddington balked.

Weddington was confident. Her parents had raised her and her younger siblings to believe, she later recalled, that they “could do whatever they wanted,” and so she had—from soloing in the church choir to serving as secretary of her college student body. But her body of legal work was sparse—a few divorces and wills, an adoption. She suggested that the group hire a lawyer in a firm, she recalled, “with research and secretarial backup.”

The women, however, wanted Weddington. So back to the library she went, comforted by the thought, she later wrote, that any suit she filed would simply back the growing number of suits that already contested abortion laws in other states.

Still, the drafting of documents was daunting. Weddington again wondered if the case might be better handled by a lawyer with knowledge of federal courts and procedure. A former classmate turned clerk leapt to mind. On December 3, she phoned Linda Coffee.

Coffee was delighted. She’d arrived at this same juncture and simply needed a plaintiff. Weddington suggested that Coffee file suit on behalf of the alumnae group in Austin. Coffee agreed and typed Weddington a letter the next day. “Would you consider being co-counsel in the event that a suit is actually filed?” she wrote. “I have always found that it is a great deal more fun to work with someone on a lawsuit of this nature.” Weddington phoned to accept.

Coffee worried, however, that because the Austin group was not a pregnant woman, it might not have standing in the eyes of the court. Besides, only a case filed in Dallas could land on the sympathetic desk of Coffee’s mentor, Judge Hughes. The search for a plaintiff thus continued, extending into late January, when an exultant Coffee phoned Weddington to tell of the pregnant woman who’d just left her office.

Days later, Norma was all belly and blue jeans when she met the two lawyers for pizza in a restaurant popular with SMU students. Seeing Coffee again made Norma anxious. But Norma was taken with Weddington, strawberry-blonde and curvy and just two years older than she. “She was wholesome and robust and had things happening!” said Norma. “I fell in love with Sarah. She had all this hair.”

Over a tablecloth of red and white gingham, talk turned to the inalienable rights of women. The lawyers asked, recalled Norma, if it was not a good thing that women could smoke in public, could vote. Norma agreed that it was, and then that women ought to have the right to an abortion, too.

Still, it was not conviction that had led Norma to Columbo’s Pizza Parlor this winter afternoon; it was happenstance, the fact that her doctor happened to know McCluskey who happened to know Coffee. And Norma again made clear that she did not want to further a cause; she wanted an abortion. Weddington repeated what Coffee had said, about her probably being too far along. “I’m not saying I misunderstood,” said Norma. “But I thought we were all real clear on what I really wanted.”

Had Coffee and Weddington really wanted to help their potential client get an abortion, they might have at least tried. As Victoria Foe, a biology student who worked with Weddington on the referral network in Austin, recalled: “In desperate situations, women up to 20 weeks were not turned away.” And the lawyers might have taken Norma to a doctor for an X-ray so as to better gauge how far along she actually was. If there was time to end her pregnancy, they might have asked a judge to issue a temporary restraining order to prevent state officials from enforcing the law against their client. Or they might have sent Norma to a clinic in their network—be it in Piedras Negras, just over the Mexican border (where both Weddington and Foe had had abortions), or in California, where every Friday a group of Texas women flew. “American [Airlines] was the plane,” Weddington recalled decades later. “About 10 women every Friday went to California and then they were back late on Sunday.”

But the lawyers did none of those things. It didn’t matter that only months before, Weddington had helped to write the American Bar Association’s code of ethical standards, which instructed that every lawyer must work “solely for the benefit of his client.” Weddington and Coffee had interests of their own. They wished to file a lawsuit. And, as the law professor Kevin McMunigal later noted, they now set aside Norma’s desire for an abortion “in favor of the collective interests of the abortion rights cause.”

It remained possible that Norma might yet spurn her lawyers. She had considerations beyond theirs. And so, in January 1970, Coffee and Weddington decided to file a second suit on behalf of a second plaintiff Coffee had found that same month. Her name was Marsha King. She was unlike Norma in almost every way.

King had a graduate degree in physics, a job as an engineer, a husband. She’d been in poor health the previous summer—her vision and muscles and mood faltering. A doctor had suspected birth control was to blame, and forgoing her pills did help. But when, in October, King got pregnant (despite using a diaphragm), she was distraught. For she still felt ill—and ill-prepared to have a child. An abortion in Mexico was successful but traumatic.

The experience had left King, at age 26, deeply committed to abortion reform, and in January, she gave a talk about it to a women’s group at a Dallas Unitarian church. Coffee spoke to the same group, and King told the lawyer that she and her husband were willing to file suit. Coffee was delighted; the Kings were impassioned and smart. They were not, however, pregnant, and Coffee worried that a court might find that they did not have standing because they would not have a personal stake in the outcome of a trial.

Coffee and Weddington nonetheless decided to file suit on behalf not only of Jane Roe but of Mary and John Doe too. And in February—weeks before McCluskey took Norma to see Swan Lake at Fair Park in Dallas, a pink dress tight over her big belly—Coffee sat down in the SMU library to prepare the legal ground upon which her lawsuits would stand.

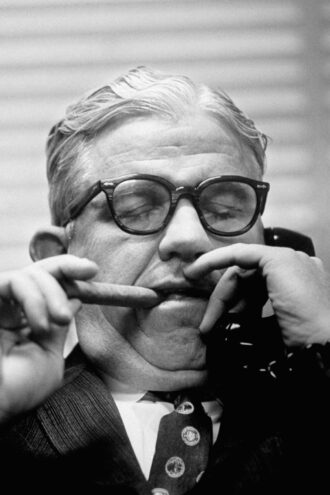

Henry Wade was an institution. He’d been the district attorney of Dallas nearly 20 of his 56 years. And he knew everybody, had spoken not only with LBJ and JFK but Lee Harvey Oswald and Jack Ruby, prosecuting the last.

In turn, everybody knew Wade. They knew that he chewed cigars and had two working farms and kept his phone number listed (TA3–6955). They knew that he was fierce; Wade would in time seek 30 death sentences and secure all but one.

The DA was nonetheless considered by most to be fair. The son of a judge, the whole of his allegiance was to the law. (When his older brother, Ney Wade, drove drunk, Henry put him in jail.) And, capital punishment aside, if he had a political or judicial leaning, it was decidedly left, a worldview informed by his pastor, W.B.J. Martin, a progressive Welsh theologian with a penchant for poetry. “My father was open-minded,” recalls his son Kim, a lawyer and former Assistant U.S. Attorney in Texas. “Kind of a closeted liberal Democrat.”

Wade was happy to go unrecognized. (Working for the FBI after law school, he’d posed in Ecuador as a journalist.) And that a Texas DA would keep his liberalism quiet made sense. Crime and convictions kept him employed. Says his son Kim: “I don’t think his liberal tendencies would have helped him get elected.”

Those tendencies extended to abortion. Unknown to everyone, Henry Menasco Wade was pro-choice.

Wade would never say so publicly. But almost 20 years after a lawsuit had pitted him in perpetuity against Roe, he would confide in his son—as they drove east in a Chevy pickup toward the family farm in Sachse—that he had disagreed with the abortion statutes it had been his charge to defend. Says Kim: “he was not anti-abortion.”

Wade had generally looked past the statutes; his few prosecutions regarding abortion had sought less to protect the unborn than the women carrying them, the DA targeting only the most reckless of practitioners. But no longer could he do so. For Coffee, the young and brilliant lawyer who’d once sought to work for him, had named him the defendant in Roe.

That was actually a mistake. Coffee had sought to enjoin all the district attorneys in Texas from enforcing the abortion statute, not merely Wade. She ought to have named the Texas attorney general, Crawford Martin, as defendant. But the court did not instruct Coffee and Weddington to amend their complaint, and Wade’s office readied to work together with the office of the Texas AG.

Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Wade were now part of the U.S. legal system. But when Coffee let Norma know, the plaintiff was unmoved. She was due to give birth in three months and had come, by March, to grasp that her suit would not end her pregnancy. It was, however, poised to end many others, after Coffee and Weddington amended Roe to make it a class action suit on behalf of their plaintiff and, they wrote, “all other women similarly situated.”

The lawyers laid out their plaintiff’s predicament, filing an affidavit in late May. Little more than two pages, and ostensibly written by Norma, it contained a few small errors. (Fewer than five years, for example, not six, had passed since Norma’s divorce.) Its central claims, however, were true. Jane Roe had chosen to remain anonymous to avoid the “notoriety occasioned by the lawsuit.” She considered “the decision of whether to bear a child a highly personal one.” She had not traveled to where abortion was legal because she was poor. And the abortion providers she could afford were both illegal and, potentially, dangerous.

Still, one assertion at the heart of the affidavit was not true. It was neither the economic strain of pregnancy nor the stigma of birthing an “illegitimate” child that had led Jane Roe to want an abortion. She simply did not want another child.

Norma, though, was going to have one. She was due any day.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author