I have long wondered about my mysterious great-aunt Carrie Neiman.

When I was young, Aunt Carrie struck me as a brooding, humorless relative—a very old, thin, and somber-looking woman with dark circles under her eyes, always dressed in black, with pearls around her neck and two thick gold bracelets on her wrist. She was my grandfather’s younger sister, divorced with no children, and she lived for years in Old East Dallas in an imposing three-story red-brick house on elegant Swiss Avenue.

In a way, the home echoed her demeanor. One of her great nephews, Herbert Marcus III, once described it as spooky, rather like a morgue. I remember it as an eerie, quiet, and dark home with heavy silk curtains, always tightly drawn, and a multitude of overstuffed sofas and chairs in the living room, all of them stiff and uninviting for children. The heavy mahogany table in the formal dining room was always set for yet another serious family dinner, with ornate silver, crystal goblets of dark ruby red, and the finest bone china.

My brother and sister saw it the same way: we dreaded visiting the house, especially going to the closed-in porch upstairs, where we were ushered every Sunday to pay our respects to our incapacitated and ancient cigar-smoking great-uncle Abe. He and his wife, Carrie’s older sister, Minnie, lived with Aunt Carrie, and he was cared for full-time by a white-uniformed nurse. Years earlier Uncle Abe was injured when the boiler went out in the basement. He foolishly lit a match to locate the source of the gas and the boiler exploded, burning large areas of his body.

The house, and the people in it, seemed lonely and forbidding, but there was one wonderful escape—a tall, narrow toy closet on the second floor. We children would race to it and explore its treasure of delightful toys, books, and dolls—all things Carrie had collected on her frequent buying trips to Europe—anything to keep us from the earnest discussions among the adults. In Aunt Carrie’s house, we knew that young children were to be seen and not heard.

When it was time for me to leave, I could see Aunt Carrie’s shiny long black Packard in the driveway, awaiting her summons. There were times when I got to ride in it—it was always chauffeur-driven—but I would be told to sit in a jump seat, against my wishes, rather than on the upholstered bench with the adults.

Sometimes, in the hushed confines of the car, after leaving the big house with its treasure closet, I would wonder if there was more to Great-Aunt Carrie than I ever imagined.

In 1953, when I was just 16, Aunt Carrie died of lung cancer. She passed away two months shy of her 70th birthday. I was just finishing high school and a typical self-absorbed teenager, to say the least: on the night she succumbed to cancer, I was upset because I had to give up going to my Hockaday School senior class costume party. My parents said that it wouldn’t look right for me to be seen partying.

As time went on, I learned that Aunt Carrie was, in fact, adored and respected by many in the family and in the Store, Neiman Marcus. But for years, I knew her to be a deadly serious soul, someone who talked business nonstop and had nothing in common with me, a rather spoiled, selfish teenager.

I eventually learned that my early impressions of her were flat-out wrong. What I had missed out on, while talking on the telephone or hanging out with my friends, was getting to know the thoroughly modern businesswoman who was the quiet genius behind the success of the internationally famous emporium known as Neiman Marcus.

My great-aunt, the stern-looking lady in the black dress who was visible daily in the Women’s Department on the second floor, was busy guiding the global success of one of the best-known stores in the world.

✸

Carrie Marcus was born on May 5, 1883, in Louisville, Kentucky, the fourth of five children of Jacob and Delia Bloomfield Marcus. Her parents were recently arrived Jewish immigrants from Wronke, Germany, a town on the German-Polish border. The children were a motley bunch. Theo, the oldest, was remembered by one nephew as “an awful lot of fun” and by another as grumpy and overweight. Herbert, the second oldest, was said to be forward thinking and progressive about most things, as well as a dreamer. The third in line, Minnie, was described as either a “dominating tyrant” or “dependent and shy.” Celia, the youngest, won a beauty pageant at 16, then eloped the following year.

Carrie was 10 in 1893, when Jacob and Delia moved the family from the vibrant cultured city of Louisville to the dusty little town of Hillsboro, Texas, 60 miles southwest of Dallas. One of Jacob’s cousins had prospered in Hillsboro, working with farmers as a cotton broker, or “cotton factor,” as they were also known. Jacob hoped to make it as big as his cousin, and Texas seemed ripe with opportunity for a man with ambition.

Hillsboro had a population of 5,300 nearing the turn of the twentieth century. It was the county seat and the agricultural center of Hill County, which had 41,355 residents. A post office had been built in Hillsboro 30 years earlier, and the Hillsboro Express newspaper had been in publication since before the Civil War. Jacob presumably appreciated that there was a growing Jewish community in Hillsboro, to go along with plenty of cotton and several established gins and textile mills. There were some wealthy families in Hillsboro—almost all tied to cotton—and they lived in large newly built Victorian homes around the town square, many with a hitching post in front. Despite the handful of wealthy residents, the town had precious few cultural outlets, though, and life in Hillsboro was a big adjustment for the Marcuses, who loved literature, art, and music.

As Jacob joined his cousin in the cotton business, his children were educated mostly at home. Jacob and Delia believed in a kind of Germanic excellence and exceptionalism. Unlike many families in Hillsboro, the Marcuses listened to classical music and read voraciously. Although they had little money, they began building a substantial library that included the classics of Western civilization. They devoured the latest news from Europe in the English and German newspapers that somehow found their way to the Texas hamlet. The Spectator, from London, was a favorite. At an early age, Carrie developed an interest in European-inspired art and fashion, influenced, in part, by her parents and by her constant reading of books, newspapers, and magazines from Germany, France, and England. While it is unclear whether the Marcuses regularly spoke German at home, Carrie was certainly able to read the German-language materials that came into the house.

Herbert, five years older than Carrie, was a restless teenager and he found work in a clothing store. But with no cultural institutions, Hillsboro in the evenings was often dull, and after four years there, he decided that small-town life was not for him. In 1899, determined to find a more cultured city, Herbert left for the big town to the north—Dallas.

With a population of 38,000 in 1900, Dallas was seven times larger than Hillsboro, but it was hardly a metropolis. As in Hillsboro, many of the principal streets in Dallas were unpaved and transportation was by horse-drawn carriage or cart, both of which had to fight for the right of way with trains that crisscrossed downtown Dallas. There were 46 saloons on Elm Street (where Neiman Marcus would eventually open), and with men stumbling in and out of them at lunchtime, the city could be a rough place for a single woman. In parts of downtown, it was said that a woman seen walking alone on the city’s streets even in daylight was not considered a lady. The promoters of a new subdivision called Highland Park claimed that downtown Dallas was nothing but “business houses, saloons, dust, and heat.”

Yet Dallas was beginning to show some signs of sophistication. It already had its Red Book, which its publisher claimed was the first register of “high society” in the state of Texas. The city also had a symphony orchestra and an opera company, and it boasted a Shakespeare Club. Dallas was clearly a city on the rise, a big step up from the little town that Herbert had left behind.

Soon after arriving in Dallas, Herbert found a job as a shoe salesman at Sanger Brothers, which, according to Leon Harris’ 1979 book, Merchant Princes, was “the greatest dry goods company west of the Mississippi.” Although Herbert had not completed college, much less grade school or high school, he excelled at selling shoes and interacting with customers throughout the store. Sanger Brothers’ extraordinarily successful owner, Philip Sanger, recognized Herbert’s strong ambition and his phenomenal work ethic, and soon he promoted Herbert to buyer of boys’ clothing. Despite, or perhaps because of, his humble upbringing, Herbert quickly developed expensive tastes, especially in clothes. Investing virtually all of his earnings in his wardrobe, he wore the finest suits and shoes, while bringing his lunch to work, carried in a brown paper bag.

Dallas was clearly a city on the rise, a big step up from the little town that Herbert had left behind.

Carrie, still a teenager living in Hillsboro, was anxious to join her older sibling in Dallas but first had to convince her parents to let her go, which was not easy. They worried that she would be a financial burden on Herbert. But, after much effort, she convinced them that she would find a job and support herself. In 1901, she moved to Dallas and immediately went to work at a specialty store called A. Harris & Co., which had been founded 14 years earlier, in 1887. She was put in charge of selling women’s blouses, earning $10 a week (about $300 a week in 2020 dollars).

At the age of 18, Carrie displayed charm, impeccable manners, and a desire to learn, qualities that helped her do well in the brand-new business of selling ready-to-wear clothes. While working on the sales floor, she learned that there was an art to making customers feel special, and she was determined to excel at it. She gave each customer personal attention, a skill that she would hone and develop for years to come—to the point that she would be unsurpassed in American retailing during the first half of the twentieth century.

Carrie, wise beyond her years, wanted financial independence when she moved to Dallas, and she found it, even managing to save a little money. Like her brother Herbert, who was quickly promoted at Sanger Brothers, Carrie advanced at A. Harris to a position as a buyer for the women’s blouse department. Drawing on her knowledge of fashion from Paris and Germany, garnered from her consumption of European newspapers and magazines, Carrie displayed extraordinary self-confidence and an impressive sense of style. She was not afraid to purchase clothing and goods that were vastly different from what other Dallas stores were offering. Instead of relying on the tried and true, Carrie courageously bought the newest and most sophisticated styles, paying special attention to fine fabrics, clean lines, and superb workmanship. She saw her salary more than double, to $25 a week, making her one of the highest paid women in Dallas. She was already a standout, and she was only getting started.

✸

Leon Harris, a former vice president at A. Harris and grandson of the store’s founder, says in his book Merchant Princes that Carrie (whom he describes as Herbert’s “slim, dark, doe-eyed, pre-Raphaelite younger sister”) became one of the store’s best saleswomen, despite not having an extensive formal education and never having traveled far, except in her mind and in the world of books and articles: “She revealed a sure sense of fashion not only extraordinary for an uneducated and untraveled woman not yet twenty, but one never equaled either by her brother or her nephew Stanley and not surpassed by any other American retailer.”

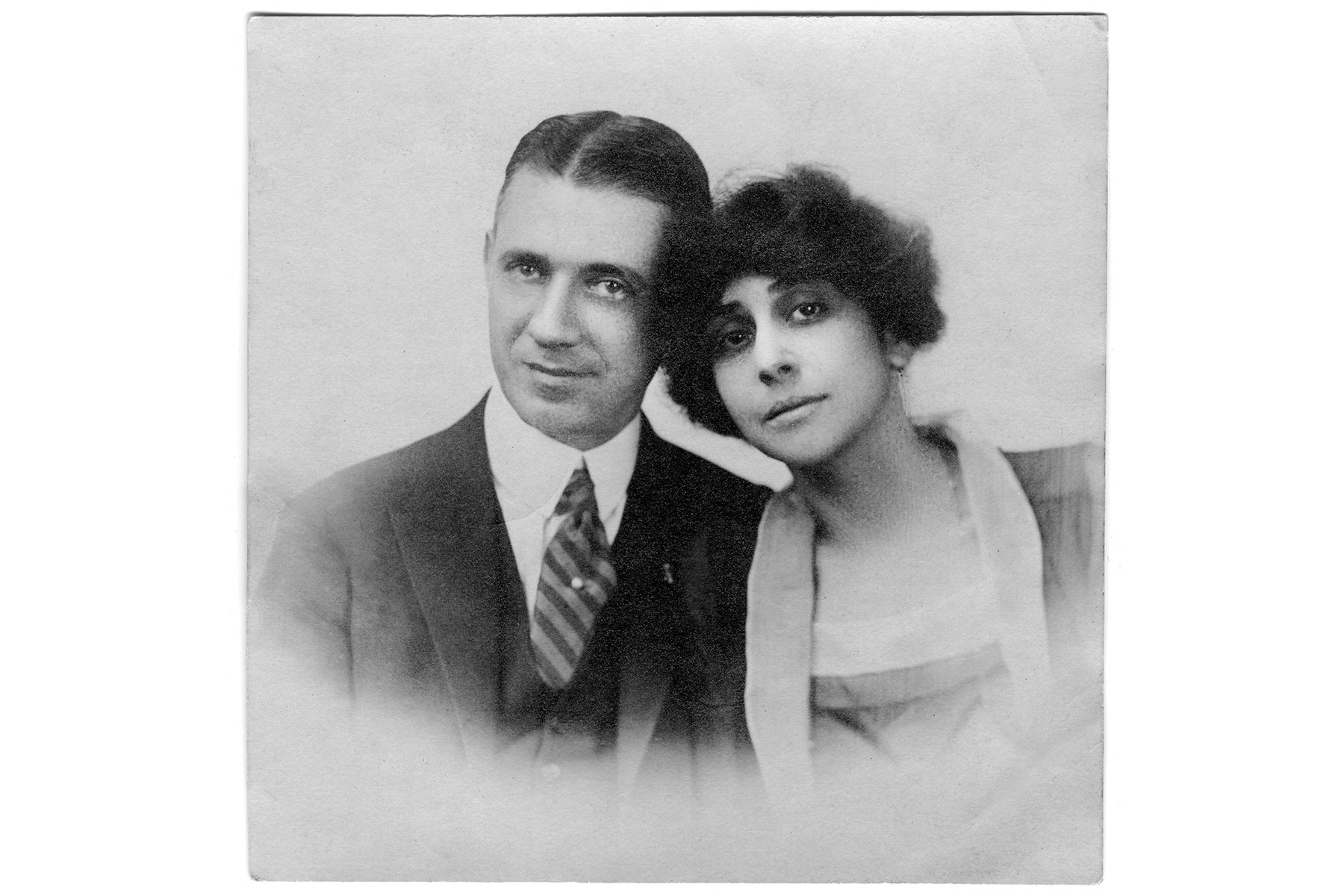

In addition to her exemplary retail skills and eye for quality goods, Carrie was stunningly beautiful, and she caught the eye of several Texas gentlemen inside and outside the store. Among her many admirers was Abraham Lincoln Neiman, called Al because of his initials. He was taken with Carrie the moment he met her. “Carrie had a regal bearing,” D Magazine writer Tom Peeler observed in 1984, “a striking composure and an enchanting gaze that could make a gentleman swoon. Al undertook a whirlwind courtship of this pearl of the Texas prairie.”

Al Neiman was born on the Fourth of July 1880 in Pittsburgh and grew up in Ohio, at the Cleveland Jewish Orphans Home. Not much is known about his early years, other than that life in the orphanage, not surprisingly, was miserable. With only a grade-school education, he left Cleveland as a teenager to become a traveling salesman, or, as it was known in those days, a “drummer.” By the time he was 24, Al was living in Fort Worth and had started a profitable business called American Salvage Company.

His job was putting on sales. That consisted of helping merchants sell their markdowns (and even augmenting the sale merchandise by skillfully buying closeouts from manufacturers) by whatever flamboyant means could be assembled: a brass band or drum-and-bugle corps, a fire department parade, hyperbolic banners promising unbelievable bargains hanging across the town’s main street. In the days before movies, radio, or television, Al’s street theater was free entertainment. It brought out most of a town’s citizens and attracted farm families from miles around. “Al had an amazing ability to whip up excitement and help less-imaginative merchants get rid of their mistakes,” according to Leon Harris.

Although it was mostly small country-store merchants who hired Al to sell their markdowns, occasionally finer stores in larger cities hired him, including A. Harris. Although it’s a bit unclear how Al Neiman met Carrie Marcus, it is likely that they were introduced in January 1905, when Al was putting on a sale for A. Harris. When they talked for the first time, Carrie was swept off her feet by the handsome and engaging, though sometimes self-centered, Al.

After a short courtship, they were married by a justice of the peace, on April 25, 1905. Carrie was 21; Al was 25. Physically, they were a good match—both tall, slim, dark, and handsome. But not everyone thought it was a match made in heaven. Carrie’s nephew Stanley Marcus wrote in his 1974 book, Minding the Store, that Carrie was “the essence of kindness and gentleness, with a reserved manner[,] which caused many of her friends to wonder how she could have been attracted to the flamboyant and egotistical Al Neiman.”

Like his brother-in-law Herbert—a big dreamer who worked hard in the retail business—Al had big plans for American Salvage Company. He was ready to make his own starry ambitions a reality, and he told whoever would listen. Shortly after he and Carrie married, he convinced his wife and brother-in-law to partner with him in the salvage business and move to Atlanta, Georgia, which Al believed was a wealthier and more sophisticated city than Dallas.

After Atlanta was rebuilt in the wake of the Civil War, it had begun to grow, not only as part of the antebellum cotton-plantation economy but as a distribution and manufacturing center. Al, ever the salesman, convinced Carrie and Herbert that his company would be an even greater success in Atlanta than it had been in Texas. Herbert was immediately open to the idea, largely because of a recent stumble on his own career path: he was working at Sanger Brothers, when in 1905 his new young wife became pregnant with their first child. With his family expanding, Herbert went to the store’s president, Alex Sanger, and asked for a raise. Sanger offered Herbert a meager $1.87 a week raise. According to Leon Harris, “The offer was not only insufficient for his growing need but, perhaps more important, it so wounded the growing ego of the poverty-proud Marcus that he quit.” Decades later, when Marcus’ own store became far grander and more famous than Sanger Brothers, Herbert liked to say that if Alex Sanger had only offered him a bigger raise, he probably would have remained at Sanger Brothers and never built Neiman Marcus as competition.

Atlanta, at the turn of that century, was no larger than Dallas, and to Carrie and Herbert it did not seem more sophisticated, despite what Al had promised. But with Herbert, Carrie, and Al all working at putting on sales, the company’s profits soared. Merchants in rural areas outside of Atlanta were drawn to the spectacle that the company provided and the instant relief when they were able to get rid of unwanted merchandise or simply raise cash for their stores. The threesome provided their clients excellent customer service, and Al especially was riding high on his financial success. Within only months of their arrival in Atlanta, however, not all was well in the family, which now included Herbert’s wife, Minnie, and their 1-year-old son, Stanley. Despite their sizable income, Carrie and Herbert were as unhappy as Al was happy.

Unlike the orphaned Al, Carrie and Herbert had a cultured upbringing. As children they had enjoyed classical music, literature in several languages, and intellectual discussion at home. And they never had the appearance of being people of little means. “Aunt Carrie was an extraordinary woman,” Stanley Marcus wrote. “She possessed a queenly quality which she carried as if to the manner born. She and my father were born with an appreciation for beauty and fine quality. They were both perfectionists early in their lives, and concurred with Oscar Wilde’s declaration, ‘I have the simplest tastes. I am easily satisfied with the best.’ ”

Carrie and Herbert were sophisticated and had refined tastes, but the business they were in was anything but refined. They finally admitted to Al that they viewed the salvage business as an unsavory way to make a living. They explained that they longed to open an exclusive women’s ready-to-wear store in Dallas and to have a lifestyle not unlike those of the Sanger and Harris families, for whom they had worked. Herbert and Carrie spent their evenings talking about fine-quality garments and the kind of elegant, cultured way of life they hoped to enjoy one day.

There was one other reason that Carrie and Herbert wanted to return to Texas. Both were terribly homesick for their larger family, to whom they were deeply devoted. Al did not have family, other than his new wife, Carrie, and clearly did not feel the same desperate longing to return to Dallas. But, bowing to his wife’s and brother-in-law’s strong wish, he agreed to do so.

✸

Leaving Atlanta after less than two years was not as hasty or irrational as it might have appeared to an outsider. The partners already had two attractive buyout offers for their company. One of the offers was from an Atlanta merchant for $25,000 in cash. The other offer came from a firm trying to sell the Missouri or Kansas franchise of a product founded twelve years earlier called Coca-Cola. The threesome, all still in their 20s, decided that operating a Coca-Cola franchise would be too risky. They were not going to be duped by a sugary soft drink that sold at soda fountains for five cents a glass and that, while popular at the moment, might not have staying power. Instead, they chose what they considered the safer bet—$25,000 cash.

Decades later, Stanley Marcus liked to tell friends and associates that Neiman Marcus was founded on a poor business decision: his father’s, aunt’s, and uncle’s choice to take cash for their company rather than a franchise in what would become one of the most successful and popular products in American history. If in the long run it was a poor choice, in the short term it offered just what they were searching for, the cash to pursue their dream of opening an exclusive women’s ready-to-wear store in Dallas.

They already had the right stuff to run such an enterprise. They had experience in buying, selling, and promotion, and they recognized fine quality. Physically, all three of them, tall and imposing, made a great first impression. Still, most people would have considered their proposition to be daunting at the least. As Stanley Marcus wrote in Minding the Store, “It took courage to come into the same town dominated by Sanger Brothers. But courage they didn’t lack, nor were they bashful or overly modest in their evaluation of their own standards of good taste and fashion.”

To Dallas’ already successful merchants, what Carrie, Al, and Herbert were planning to do seemed “risky to the point of foolhardiness,” writes Leon Harris in Merchant Princes. “They proposed to open a frankly expensive store (years before the oil boom) in a town as yet far from rich. Even riskier was their insistence that this store’s high-priced clothing would not be custom-made but ready-to-wear.” Harris continues:

“Fashionable rich women of Dallas in 1907 still had their clothes made to order in New York, and by the best local dressmakers, including Miss Ward of Sanger Brothers, Madame Bartel of A. Harris & Co., and Titche-Goettinger’s Madame Snow. Neiman Marcus promised that its revolutionary ready-made clothes would be even finer than made-to-order fashions. To ensure the proper fit for these off-the-rack outfits, Neiman Marcus hired Madame Bartel away from A. Harris & Co., but made plain that she would only fit and alter ready-made fashions—thus offering the best of both worlds.”

The “piece-goods” department of most fashion stores of that era was usually the most important contributor to the store’s reputation, turnover, and profits. The department supplied both the store’s dressmaker and the many private dressmakers then in every community, as well as the great majority of women who made their own clothes and their family’s clothes. Neiman Marcus had no piece-goods department.

Carrie, Al, and Herbert, now with $25,000 in hand, pooled their savings and sought financial help from family members. Carrie’s and Herbert’s oldest brother, Theo, had become a successful cotton broker and contributed to the startup business. He and other family members were given minority shares in the new enterprise in exchange for their contributions. In the end, the threesome would have approximately $50,000 to open a store. In early 1907—with an opening day estimated for August or September—they began to work on their new endeavor, carefully dividing up responsibilities. Herbert would be in charge of the books and would write most of the store’s advertisements, while Al was in charge of promotion. Together Herbert and Al handled the finances and logistics of securing a space in a downtown Dallas building.

Carrie had only one job, but it was the most critical job of all. She was in charge of buying all of the merchandise for the new store. Carrie traveled by train to New York on an initial buying trip, armed with only her own fashion sense and a vague idea of what types of materials and styles her future clientele might want. She stayed close to her original ideas of fashion—sophisticated, clean lines, and good-quality materials—and returned with some of the latest women’s styles from New York and Paris to present to her husband and brother. In an interview years later with the Christian Science Monitor, Carrie recalled, “I marvel at my courage on that first buying trip.” She knew that the store’s hopes for success were completely dependent on her choosing the right clothes, clothes that her brand-new thus far unknown customers would want. Should she choose the wrong garments, the store would fail before it even got started.

In total, she purchased $17,000 worth of merchandise, the very best clothing in satin, silk, taffeta, and wool. The merchandise was the new enterprise’s largest expense. Furnishing the store with light fixtures, carpet, and display cases cost $12,000. Rent was another $9,000. Carrie need not have worried about her buying abilities: within a month of Neiman Marcus’ opening, the entire stock of merchandise had sold out.

They chose for their location a 50–foot storefront in a four-story building in the heart of the retail district.

They chose for their location a 50-foot storefront in a four-story building in the heart of the retail district, at the corner of Elm and Murphy streets. Dallas had grown to a city of 86,000 by 1907, nearly doubling in size in the time that Carrie, Al, and Herbert were in Atlanta. Now Dallas seemed, in the threesome’s eyes at least, primed for a beautiful retail store. But just as they were set to open Neiman Marcus, both Carrie and Herbert became seriously ill. Herbert came down with typhoid fever and couldn’t leave his bed. Carrie had suffered a miscarriage a few weeks earlier and was still in critical condition in Millikin Hospital on Akard Street downtown. As a result, on Neiman Marcus’ opening day, the only store principal on hand to greet shoppers was Al. The egotistical Al probably enjoyed having all of the focus on himself, although he did have help with customer requests from a staff of 35 salespeople.

What was remarkable to many citizens of Dallas was the youth of the owners of the exciting new enterprise. Herbert was barely 29, Al 27, and Carrie only 24. But the language that they used in their first advertising of Neiman Marcus made clear that although they were young, they were not novices. They had impeccable taste and great confidence in themselves and their judgment, and they understood promotion as well as any merchants in the Southwest.

On Sunday, September 8, 1907, a full-page advertisement appeared in the Dallas Morning News announcing “the opening of the New and Exclusive Shopping Place for Fashionable Women, devoted to the selling of Ready-to-Wear Apparel” and naming Neiman Marcus “The Outer-Garment Shop.” It stated that “Tuesday, September tenth, marks the advent of a new shopping place in Dallas—a store of Quality, a Specialty store—the only store in the City whose stocks are strictly confined to Ladies’ Outer Garments and Millinery and presenting wider varieties and more exclusive lines than any other store in the South.” The ad continued:

“Our decision to conduct a store in Dallas was not reached on impulse. We studied the field thoroughly and saw that there was a real necessity for a shopping place such as ours. Our preparations have not been hasty. We have spent months in planning the interior, which is without equal in the South.

“We Will Improve Ready-to-Wear Merchandising. A store can be bettered by specialized attention. Knowledge applied to one thing insures best results. We began our intended innovation at the very foundation; that is to say with the builders of Women’s Garments. We have secured exclusive lines which have never been shown in Texas before, garments that stand in a class alone as to character and fit.

“Our Styles. All the pages of all the fashion journals, American and Foreign, can suggest no more than the open book of realism now here, composed of Suits, Dresses, and Wraps of every favored style. The selection will meet every taste, every occasion and every price.

“Our Qualities and Values. As well as the Store of Fashions we will be known as the Store of Quality and Superior Values. We shall be hypercritical in our selections. Only the finest productions of the best garment makers are good enough for us. Every article of apparel shown will bear evidence, in its touches of exclusiveness, in its chic and grace and splendid finish, to the most skillful and thorough workmanship.”

Another newspaper advertisement for the Store described the principals this way:

“Mr. A.L. Neiman is a businessman of conceded ability and as a thorough judge of merchandise has few equals. Mr. Herbert Marcus has for several years been at the head of a department in one of the leading establishments of Dallas, and is well and favorably known to the shoppers in Dallas. Mrs. A.L. Neiman, formerly Miss Carrie Marcus, who is at the head of the buying and general floor manager for the new firm, is too well known to Dallas shoppers to need an introduction. Mrs. Neiman’s judgment in the matter of correct and artistic dress has long been recognized as authority by the most exacting buyers of women’s garments.”

Their advertising did a great job of convincing readers that only the finest quality items would be available at the Store. In fact, it did too great a job. Potential customers were left with the impression that all that top-quality merchandise would translate to sky-high prices. Within days, Al was forced to put out another advertisement, which amounted to a correction, stating clearly that, although the Store did offer the highest quality merchandise, it was, nevertheless, affordable. He explained that the women’s garments being offered were available at several price points.

Many of the wide-eyed visitors to the Store on opening day were there just to see and not to buy, but many shared their opinions about the new Store. One visitor’s impressions were recorded in the pages of Fortune magazine. That visitor, who was from New York, exclaimed, “I saw dresses that tied those in L.P. Hollander’s on Fifth Avenue. Absolutely stunning evening gowns. Coats tailored to beat the band. Furs that must have come from Revillon Freres.”

Despite the hard work and planning by the owners, the timing of the Store’s opening was hardly propitious. In October, just a month after the Store opened, the nation’s economy was badly shaken by the money panic of 1907. A financial crisis was set off by a frenzy of bank withdrawals caused by public distrust of the nation’s banking system, and almost overnight the panic wiped out 13 New York banks and bankrupted several major railroads. People from coast to coast stopped spending. The nation’s economy ground to a halt.

Get the AtHome Newsletter

Author