Collin Yarbrough spent 8 years working as a pipeline engineer for Atmos Energy before he quit to focus on Full Circle Bakery, the community service-minded cookie-making operation he had founded with his mother—its proceeds go entirely to nonprofits like CitySquare. Around the same time, in 2019, he went into seminary at SMU’s Perkins School of Theology. It’s a background that in many ways made the Lake Highlands native uniquely prepared to write a book about how years of infrastructure development shaped by racist public policy turned Dallas into one of the most unequal cities in the U.S.

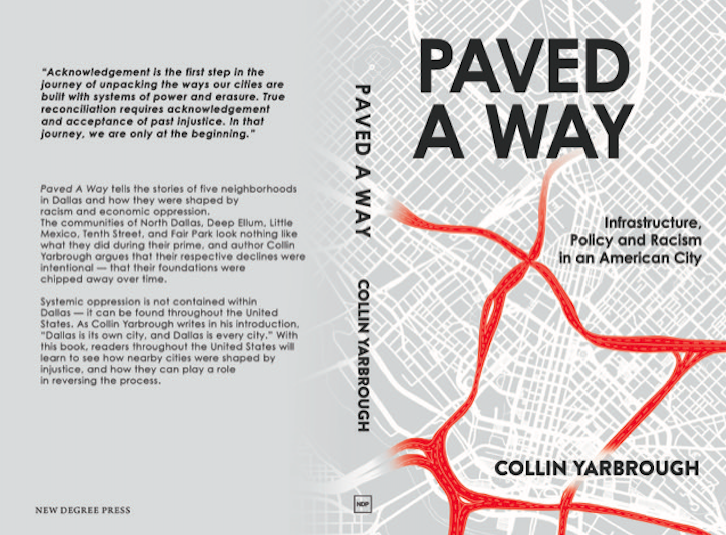

Paved A Way: Infrastructure, Policy and Racism in an American City, is available now on Amazon and coming soon to a Dallas bookstore near you. In the book, Yarbrough tells the stories of neighborhoods like Little Mexico, whose erasure began with the construction of the Dallas North Tollway, although there are still some remnants of the once-thriving Hispanic community in what is today Uptown. There’s Deep Ellum, split by I-345. And Fair Park, where Black neighborhoods were seized by eminent domain and paved over with parking lots to bring more White people to the State Fair of Texas.

Paved A Way shares some DNA with books like The Accommodation and White Metropolis, which similarly cover how a history of racism and inequality shaped the Dallas of today. Yarbrough’s book is also a call to action.

“These communities are still fighting,” he says. “Little Mexico may be gone, but West Dallas is having to face concrete batch plants coming in and trying to grapple with Trinity Groves. It’s the same thing, just in a different location with different names and different actors. An engaged coalition of community members is, by and large, one of the most powerful things that I’ve seen in Dallas and in other cities that can really make an impact on keeping this kind of injustice from repeating.”

I got Yarbrough on the phone this week to talk about Paved A Way and the story behind every highway. This interview was condensed and edited for clarity.

How’d you go from seminary to writing this book?

Seminary is actually the reason I left seminary. One of the classes I took was on the Church and social context. And I really began to think about the ways the Church exists outside of the traditional church setting. I took a couple of Old Testament classes. And so I was beginning to understand this idea of justice and what justice means and how different it can look across different contexts. Then in spring of last year, I took a context and impact of design class in the School of Engineering’s design and innovation program. We watched The Pruitt-Igoe Myth, this documentary about a failed housing project in St. Louis. Everything started to click, and the wheel started to turn in my head. All of the understandings of justice that were informed by my theological training are now melding with my eight years in infrastructure, in pipeline engineering. And I just really started to dig deep into that.

We had to write a paper on the context and impact of a large design element in Dallas. You’ve got like the Meyerson [Symphony Center] and the Nasher [Sculpture Center]. And then, way down the list, one of the examples was Central Expressway. I was like, ‘That’s weird. There’s a highway, there’s nothing really interesting.’ But that’s when I started stumbling into the articles—I found a New York Times article talking about the removal and reinterment of the bodies in the Freedman’s Cemetery. That was the catalyzing moment for me. There was something so unjust about that, that we would move 1,127 Black bodies to make extra space for a highway. And it just spiraled from there. Everywhere you look, every highway in Dallas has a story.

A lot of people who grew up in Dallas have similar sort of journeys, of being unaware of the city’s history and then being shocked when they learn about some of this stuff. Dallas has this reputation for paving over its own past. What, in your research for this book, helps explain that reputation? Why is that such a part of the city’s identity?

I have lived my entire life in this city not having to think about the city, because the city was built and designed by me—by people who look like me. The city of Dallas has always served my interests as a White male. Our city, for so long, was built, designed, funded, and controlled by White interests. White business structures controlled who was on the [City] Council and made things happen, whether it was zoning changes or highway placement. And that lack of representation and the way that has continued to emanate through the decades—the inequalities of today are because of inequalities that existed 50, 70, 100 years ago. They’re still rippling through the built environment.

How did you go about researching the book, and digging up those stories that have been buried? The first half of the book goes into these five kind of case studies of particular neighborhoods.

What I wanted to do was elevate narratives that were not the predominant narratives—that were not the ones centering on White actors as much as possible. Each of these case studies is really trying to paint the picture of the neighborhood with people who were from that neighborhood, to try to engage in some level of narrative change. I was trying to bring all the narratives together in one place to show that pattern of injustice. I didn’t even cover all of them. I just picked five. But I wanted to recenter those voices of people from each neighborhood, if that was still possible. In some neighborhoods, it wasn’t possible, like North Dallas. But Little Mexico, some people are still around. 10th Street is obviously still there and hanging on by a thread.

That was my research process: How can I get as close to the community there as possible, while also pulling in the infrastructure decisions being made and what that felt like? That’s the privilege of being White in Dallas. You don’t have to think about that. You don’t have to imagine what it’s like to have a lead smelter or a Shingle Mountain next to your neighborhood. I wanted people to understand what that felt like, to have spot zoning take away houses and slowly destroy the fabric of your neighborhood. How housing values are depressed, which then makes it easy for highways to jump through, the impacts of eminent domain and things like that.

There’s a line in the book: “Dallas is its own city, and Dallas is every city.” What can every city learn from what’s happened in Dallas? How can we apply it to doing things differently?

I think the biggest thing is being engaged in the civic process. Because the battles have not stopped. They’ve changed. They’ve moved locations. But these battles that I describe in the book, these communities are still fighting. Little Mexico may be gone, but West Dallas is having to face concrete batch plants coming in and trying to grapple with Trinity Groves. It’s the same thing, just in a different location with different names and different actors. An engaged coalition of community members is, by and large, one of the most powerful things that I’ve seen in Dallas and in other cities that can really make an impact on keeping this kind of injustice from repeating.