I’M LUCKY ENOUGH to have a father who keeps his critical judgments about me to himself. In those moments when he is able to suspend his disbelief, he feels, I think, that 1 am successful. And he, I know, is proud of this success (about which I am not so sure). What he doesn’t know is what I feel about him and what I feel I owe him. As I talk with other sons, I realize that my father is not alone in this lack of knowledge. And we, the sons, in turn, do not seem to know much about what our fathers feel about us.

Why is this code of silence chosen? Does what is left unsaid form the bond? That we have somehow let each other down-is this what we fear to acknowledge? Keeping our distance keeps us frozen apart.

Oliver Hailey, a playwright from Borger, Texas, was finally able to tell his father what he felt in a play called Who’s Happy Now. His father came to Los Angeles to see the play. After the performance, he went backstage and hugged the actors and actresses. Later, as father and son drove to a restaurant, the elder Hailey said, “You know, I’d still be laughing if it wasn’t about me.”

Hailey and his father had been estranged for years. When Oliver got out of the Marines, he persuaded his mother and brother to leave their father and live with him. Hailey felt that his father had mistreated his mother. When his mother divorced his father, Hailey believed it was he, the son, who had ended their marriage, and he didn’t like the feeling. Ten years later, when he wrote Who’s Happy Now, Hailey told me that the play allowed him to see that situation from his father’s viewpoint. “The play,” Hailey said, allowed us to be friends again.” He added, “As a boy, I was simply not the son my father wanted. He wanted an athlete, and I always had my head in a book. He didn’t understand where I was headed. And I didn’t understand his pain.”

Hailey’s father is dead now. At the end of our conversation, Hailey said, “I miss him, but when he died, I didn’t have feelings of remorse or guilt-even to the point of being able to choose an inexpensive casket.” Hailey says, “I tell my friends, ’Work it out while there’s still time.’ As a kid, you take sides, and just that makes you miss a lot. It’s only when you get older that you see all the complications.”

Happenstance can be far more effective than analysis in bringing fathers and sons together. When D.J. Stout, one of my co-workers, was in high school in Virginia, his father’s business went bad; then his father and mother divorced. D.J.’s anger was all directed at his father. His mother moved from Virginia back to West Texas. She had never been on her own; her life wasn’t easy. At the time, D.J. was in college in the East, but he moved back to be close to her and to help out where he could. Seeing her struggle hardened him against his father, and the father and son were out of touch for about three years.

During his junior year, D.J. went to the college infirmary. A doctor came in, looked at his card and asked D.J. whether his father was the Doyle Stout who had coached baseball and taught math at a certain Lubbock junior high school. He was. Without any prompting, the doctor told D. J. how critical the elder Stout’s influence had been to him as a student. “He was always willing to take extra time with me,” the doctor told D.J. It was his combination of kindness and toughness, the doctor said, that had helped keep him in line. He told how D.J.’s father had encouraged him to be a doctor. And once, when he had done poorly on a test, D.J.’s father had taken him out for a cherry Coke and had helped him see that the grade could be just a momentary setback.

As they talked, D.J. began to remember. He remembered the support he had received and the encouragement that his father had given him. He saw the influence his father had had on him. He remembered being taken for cherry Cokes by his father and the advice his father had offered. Hearing the doctor talk about the cherry Coke had acted as a trigger. “All of a sudden, I could see my father for what he had done for me,” D.J. said. He hadn’t forgotten the pain; he had simply remembered the efforts of his rather to be a good father. The chance meeting with a doctor he’d never seen before enabled D.J. to write a letter to his father and begin to settle up.

How do we become our fathers’ sons? With three sons of my own, I can see my slight and nearly undiscernible influence show up unpredictably. It doesn’t come from my mind-numbing speeches about the values of hard work, the dangers of inherited wealth or their aversion to public transportation. The well-meaning exaggerations about how far I had to walk to school, the caddying doubles twice a day all summer, the snow-shoveling jobs: None of this makes any impression. I have a friend who maintains that you’d have to go to the North Pole to approximate the meteorological conditions his rather recalls facing nearly every day on his paper route. My boys are far less interested in what I want them to believe and are much more interested in what I really believe and value. I guess.

Not many fathers purposely set out to be wrong; we spend an inordinate amount of energy trying to be right, especially in front of our sons. But it’s our fallibility that gives a son an opening to come closer. And in some ways, a father’s being wrong is just what a young son’s self-esteem requires most. A father who is always right is a burden as well as a myth.

The conversation with Oliver Hailey made me recall a dream I had been trying to shake. It was one of those dreams where, even after I woke, something seemed changed and forever lost. In the dream, I had decided to fly to Boston to visit my father on the following day. Then I was going to tell him all those things great and small that he had done for me. This was going to be my best attempt to set the record straight. In the dream, I went to bed and was awakened by a phone call with the message that my father had died. Now it would be too late-that’s all I could think. Maybe he already knew all that I would have told him; I doubt it. I know for sure that I don’t know all that he might have told me. But it was all just a dream; my father is still alive. There is still time-time to explain, time to settle up.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Commercial Real Estate

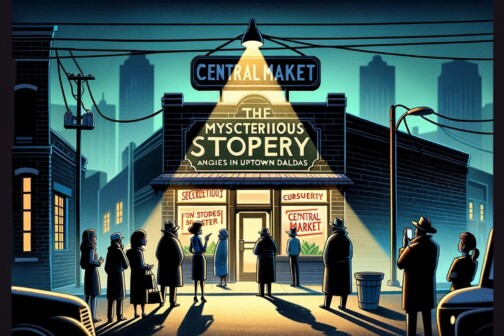

The Mystery Ownership Behind That Planned Uptown Central Market

You'll never guess.

By Tim Rogers

Local News

Dallas Assistant City Manager Robert Perez Hired to Lead Topeka’s Government

Perez parlayed his two decades of municipal experience (including two years as assistant city Manager in Dallas) into the top spot in Topeka, Kansas, sources tell D.

Business

Executive Podcast Club: DFW C-Suiters Reveal Their Top Listens

Kim Butler, Chris Trowbridge, Fred Balda, and more share the one podcast they think everyone should listen to—and why.