On Monday, Dallas County acknowledged that it became the latest local government entity to be attacked by hackers. A ransomware attack on October 19 is being investigated, Dallas County Judge Clay Lewis Jenkins said. The effort was interrupted and contained because the county uses an endpoint detection and response (EDR) tool that detects and responds to cyber threats.

The county says there is “no evidence of ongoing threat actor activity in our environment.” The statement says the incident has been contained and that any potential encryption of data was thwarted. The ransomware gang Play has claimed responsibility for the attack and threatened to release data Friday.

The group came on the scene last year and has attacked targets all over the globe. Most security experts believe that, since their techniques are similar to other Russian ransomware gangs, they are also likely linked to Russia. They got their name in part because they use a “.play” file extension.

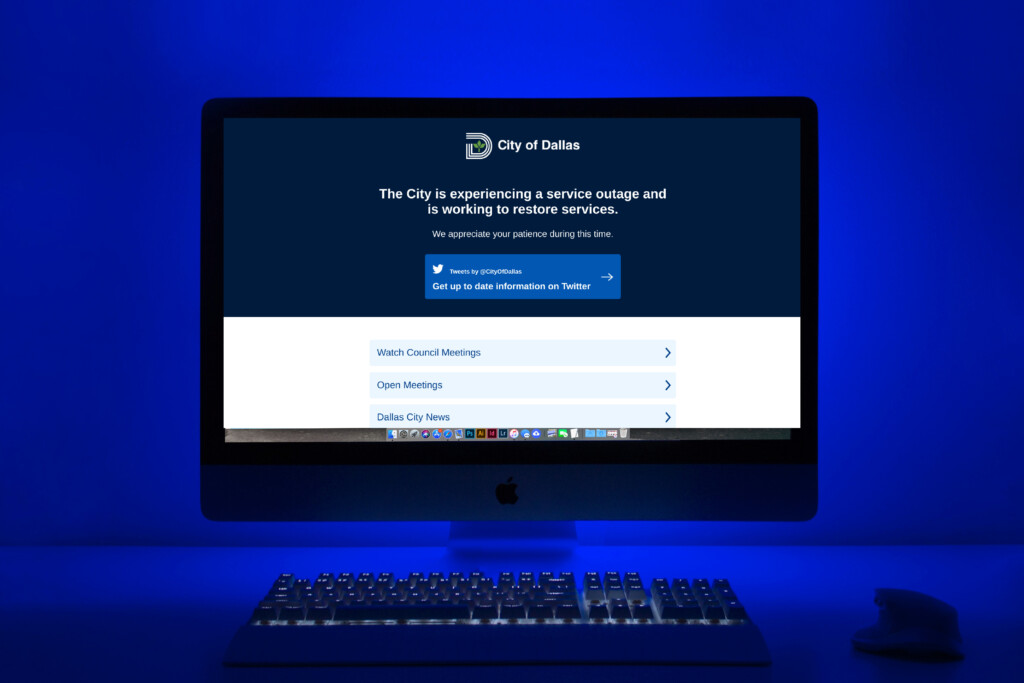

The county’s ransomware issue comes on the heels of a November 2022 attack on the Dallas Central Appraisal District, as well as a May attack on the city of Dallas. In both cases, it took months to unsnarl the two respective entities’ systems from the damage.

The appraisal district ultimately paid $170,000 in cryptocurrency, while the city spent millions to bring its system back online and recover from the attack. UT Southwestern Medical Center and HCA, the parent company of Medical City hospitals, were also hit by hackers over the summer. They went after the city of Fort Worth, but it was not considered a ransomware attack, and the damage was minimal.

The cybersecurity firm Emisoft, which is often called to help ransomware victims deal with attacks, says at least 72 local governments in the U.S. have been hit by ransomware gangs this year. At least 40 have had data stolen. The company says 107 local governments were hit last year, as well as 44 universities and colleges, 45 school districts, and 25 healthcare providers.

The state of Texas has a Department of Information Resources that tracks these attacks and often assists local governments and school districts when they are targeted. It also consults with entities to help create better cybersecurity protocols so they aren’t sitting ducks. The TDIR maintains a database of cyberattacks and intelligence gleaned from them. That database was mandated this year by Senate Bill 271, which was authored by state Sen. Nathan Johnson (D-Dallas) and state Rep. Matt Shaheen (R-Plano). Local governments must report cyberattacks to the TDIR portal as part of the bill.

We spoke to State Cybersecurity Coordinator Tony Sauerhoff in July as the city grappled with the issues surrounding its ransomware attack. Our conversation, edited for clarity, follows.

It seems like we’re seeing more of these cyber attacks on local governments and healthcare providers. What makes some of these entities so attractive?

It’s up to the attacker. We don’t know exactly why (these entities) got attacked. Were they the specific target, or were they somebody the attacker stumbled upon because they had a particular vulnerability? But often, it’s a combination of things. First of all, the vulnerabilities have to be there, but also, the entities with larger amounts of more sensitive information and money are targets.

A lot of what I’ve read has mentioned that, in particular, municipalities seem to be vulnerable because they’re often using a patchwork of third-party vendors. Different departments use different platforms with different procedures and protocols. And because of that, it’s really hard to standardize things in a way that would keep their system safe from those vulnerabilities.

Sure. I think that is part of it. Now at the same time, you can make the argument that a large corporation has different departments and things, too, and they figure out how to make it work. So sure, that that can be part of it, but that argument only goes so far. When we’re talking about municipalities—and keep in mind we have over 1,200 municipalities in the state of Texas—most of them aren’t the size of Dallas and Fort Worth. Most of them don’t have the resources that Dallas has. They’re communities that don’t have access to the personnel, the funding, and the expertise. It’s one thing not to have enough personnel, but it’s another totally different thing for someone not to have the right expertise in cybersecurity. I was talking to a school district just a week ago—they were one of our smaller school districts—and their single solitary cyber person is a first-grade computer teacher. This person is not a cybersecurity expert. And that’s what we see a lot of.

Another thing I heard from one cybersecurity expert was that when it comes to local governments and school districts, funding for cybersecurity often isn’t prioritized until it’s too late. Do you find that to be true?

I spend a lot of time in my role of state cyber security coordinator out talking to folks and groups—usually at conferences and things. I have 30 years’ worth of technical background. I find myself mostly talking to folks in leadership positions and not technical positions about the need to view cybersecurity as a business risk to the operation and consider it that way. And this isn’t just in municipalities. We see this all over the place: you get outside of IT and cybersecurity and talk to folks in leadership positions—the people who run the whole organization—and it’s all Greek to them.

But if you can break it down into a conversation about operational risk, it does bring them into the conversation. No one is secure. Aside from the NSA, for most organizations, it is a matter of how close you want to get to total security and how much you want to spend for it. Where do you draw the line? That’s a decision for a county judge, a city council, or a school board to make. But it’s about getting those kinds of folks involved in the conversation and understanding it from a risk aspect. We’re not necessarily going to get a big influx of funding just because we brought the city manager into the conversation. They still have to weigh other things on the budget against their need to improve cybersecurity. But you can help people see this as a risk and not just some needy IT person asking for money to buy a tool.

The one thing every cybersecurity expert I’ve talked to has consistently said is that these entities must stop paying the ransom—the only way to make ransomware attacks stop is to make them unprofitable. But how do you convince them to do that?

It’s in line with the U.S. government’s policy not to pay ransom for hostages, right? It just encourages more hostage-taking. The same thing applies now that we’re dealing with ransomware— it just encourages more. Because when we’re talking about ransomware, that is only about money. There are other cyber crimes we can talk about that have other motives, but ransomware is all about money. If there’s no money to be made, then there’s no reason to do it.

The problem is that it’s easier said than done for the entities that are impacted. I think it’s a bad idea to pay a ransom, but I understand if it’s an individual organization’s risk decision that has to be made. It’s a case-by-case decision. If it’s an organization that’s maybe a for-profit business and is looking at completely going out of business tomorrow because of a ransomware attack, it’s tough to say no. I don’t think anyone would argue that it’s not a bad idea to pay.

And there’s definitely the argument that you don’t know whether you’ll actually get your data back, and you don’t know whether they’re going to do it again. You’re dealing with criminals, and you’ve got to pay them first, right? You don’t know if you’re going to get the decryption key. You don’t know if they’re going to delete your data. You don’t know if they’re going to come back and tell you next year that they still have your data or if they’re gonna come back next month and exploit the same vulnerability they exploited today.

Do you think that local governments and businesses should feel pretty good if they haven’t been attacked, or could this happen to anyone?

There’s a whole side of being cyber criminals that involves getting in and pulling data out and and not wanting anyone to know that you were in there. A few years ago, the federal Office of Personnel Management had about 12 million records accessed because the Chinese were in their network for at least a year and a half. And if you had asked them 12 months into that if they were a victim of a breach, they would’ve said no. You never hear how many of those things happen, and the bad guys got in and got out, and no one ever knows. We have no idea, right? It happens all the time, and it’s happening all the time. It’s happening now. If you are asked if your organization has ever been the victim of a breach, you can only answer two ways—you can only say “yes” or “I don’t know.” You can’t answer no to that question.

What are some bare-bones things organizations and local governments can do to prevent a cyber attack? Is making sure all your software and devices are regularly updated a first line of defense, for instance?

That is a huge first action. And cyber hygiene is a term that’s used a lot, and it’s doing the basic things like installing patches and knowing what is on your network. You can’t protect what you don’t know about. So you have to know what’s on your network and what connects to your networks from a hardware standpoint. And you have to know what applications you’ve got on that hardware and what applications need to be patched.

There are a lot of frameworks out there for cybersecurity, like the CIS critical security controls, which are the industry-accepted list. There are 18 items on the list, and they consider the first five to be just basic cyber hygiene, and then they get a little more advanced. But the Center for Internet Security says that if you do the first five things really well, that protects you from 80 percent of the threats out there.

We have a program—the Texas Cyberstar Certificate Program—that we launched last year. It’s a recognition of an entity’s commitment to best practices, and we have some criteria to meet. It’s open to all public and private sector entities in the state. We require an acknowledgment from someone in a leadership position in the organization that cybersecurity is a priority, and there is a basic list of best practices as well.

Author