Sixteen years ago, the Dallas County District Attorney’s office became one of the first in the country to establish a conviction integrity unit. Craig Watkins, who served as district attorney from 2007 to 2014, made headlines locally and nationally by prioritizing exonerations of innocent people. And those exonerations came quickly: 24 people over his seven years in office. Most of these cases used DNA evidence to prove innocence.

Since Watkins lost his seat in 2014, the number of people exonerated has slowed to a steady drip. There have been just eight exonerations in Dallas County in the last nine years. There are reasons for that: easier access to pre-trial genetic testing, body cameras on police officers, and other safeguards that make it harder to put an innocent person behind bars. Harder, but not impossible.

In June, during a lengthy discussion with D Magazine, Conviction Integrity Unit Chief Cynthia Garza said the types of cases the unit now works are often more time consuming and complex than the early genetic cases. Non-DNA cases involve looking at things like lapses in procedure, the quality of eye-witness accounts, and whether the investigation was of a high enough quality to end in a conviction.

Since 2001, there have been a total of 44 exonerations in Dallas County, according to the District Attorney’s office. Sixteen of those people were found to be wrongly accused for reasons that did not involve DNA evidence.

Under Watkins’ tenure, 24 people were exonerated. Since he left office in 2015, the office has had eight exonerations—Steven Chaney and Timmy Duke in 2018 while Faith Johnson was DA, and Dennis Allen, Stanley Mozee, Quintin Alonzo, Mallory Nicholson, Martin Santillan, and Tyrone Day from 2019 to 2023, after John Creuzot took office. The other 12 were cases led by innocence projects or other attorneys.

Garza has worked in the unit since 2010 and led the office for the last six years. She is the longest tenured prosecutor in any CIU in the country, and has been involved in most of the county’s exonerations. She has also worked under four DAs: Watkins, Susan Hawk, Johnson, and Creuzot. That meant she was present for the office turmoil in the wake of Hawk’s departure. The Republican who surprised the county by unseating Watkins resigned midway through her term to treat the mental health issues that caused monthslong absences during her two years in charge.

Gov. Greg Abbott appointed Johnson to fill the seat. She built the office back up and served until losing to Creuzot in 2018. Her office saw two exonerations. (She also regularly held expungement events for individuals who had arrest records but were never convicted of a crime.)

Attorney Gary Udashen, who frequently works with the Innocence Project of Texas and has collaborated with the Dallas County DA’s office since the unit was formed, says he feels all four district attorneys were committed to making the unit work.

“They are all very different people and very different district attorneys, but they all were committed to conviction integrity and I think that’s important to know,” he said. “People in Dallas can be proud that the district attorney—no matter who it is—understands the importance of this work.”

The National Registry of Exonerations maintains a list of 46 CIUs across the country that have never had an exoneration.

“It depends on the jurisdiction, and how aggressive they are,” said Maurice Possley, a researcher who tracks exoneration data and national trends for the National Registry of Exonerations, widely regarded as the authority on conviction integrity units. “We have two lists—one with CIUS that have had exonerations and one is ones who don’t, and the ones without one…some of them have been around for almost a decade, so you have to question their motives.”

Watkins had a running start, which helped in amassing early exonerations. Between 2001 and 2007, 13 Texas prisoners were found innocent because of DNA evidence. When Watkins became DA in 2007, he ordered reviews on over 400 more cases that had been ignored by his predecessor, Bill Hill. (Hill served as DA from 1999 to 2007.)

“When Watkins came into office, the prior policy had been to routinely deny and oppose all motions, so there was a backlog in that sense,” Possley said. “It was sort of ripe—easy pickins.”

Hill wasn’t alone. Many district attorneys were reluctant to approve DNA test requests during the period he was in office. In 2001, the state adopted a post-conviction statute that allows inmates to request DNA testing.

“We have cases that we learned—or another administration that did the DNA test—that the Bill Hill administration fought the DNA test and appealed, got it affirmed, and didn’t do a test, and later on they did it, and guess what? It wasn’t that person,” Creuzot said. “That man spent extra time in prison and the statute of limitation ran out on the person who was guilty. That’s a bad outcome.”

Udashen said the Watkins administration began by reviewing cases that had been denied. Garza said the 400 or so cases yielded several that had been refused in error.

“The initial cases that came out, it seemed like, ‘Oh my gosh, they’re coming out really, really quickly,’ and it’s because we had the data to start with, and we started producing results pursuant to the DNA testing,” she said. “It sounds like it was going really fast.”

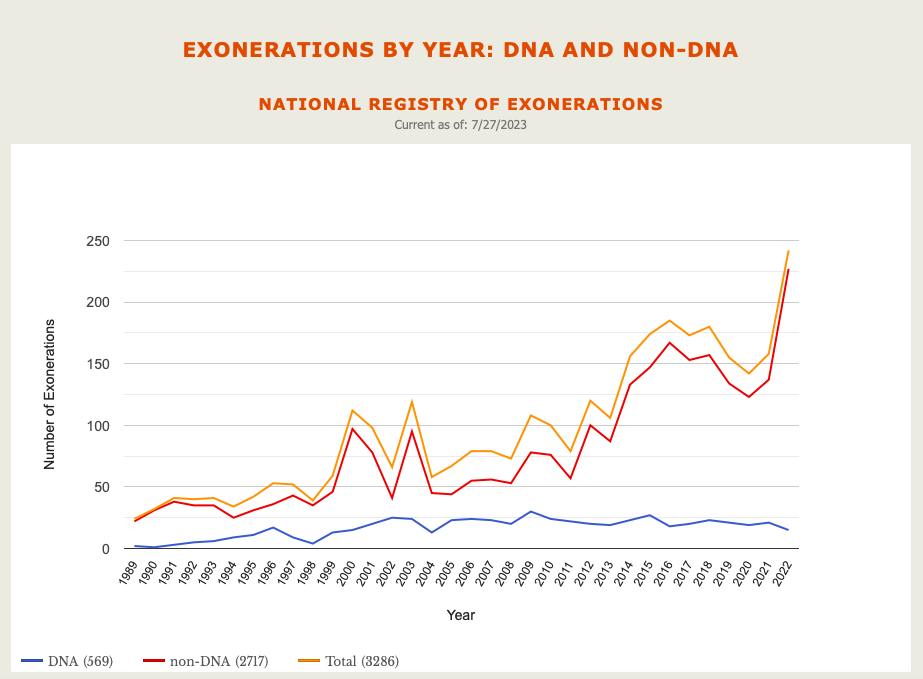

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, DNA cases in recent years have remained flat across the nation. The fewest was in 1990 (one exoneration out of 24 total) and the most occurred in 2009 (30 out of 108). In 2022, there were 15 DNA exonerations nationally, with 242 exonerations in total.

In 2007, DNA testing was a key tool for Dallas. For many who were wrongfully convicted, the technology wasn’t robust enough to produce conclusive results in earlier years. Garza said previous iterations of DNA testing only tested the Y chromosome in the sample, which is found in men and passed down directly by the father. It makes “any paternal line almost identical,” she said.

Newer tests analyze several specific fixed parts of a chromosome, which improves accuracy in DNA matches.

“The science has evolved so much from where we started off,” Garza said. “It’s like we’re light years away from where we started off, and I can’t wait to see what the future holds.”

Now, DNA testing is typically performed before trial, which makes it more difficult for new evidence to tell a different story years later.

By 2010, the unit began getting more requests to review non-DNA cases: looking for instances where perhaps there was only one eyewitness, or a jailhouse informant, or possible deviations from investigative procedures. Those, Garza said, are more difficult and take more time, because they require a painstaking review of documents and evidence. Some can take years to complete.

“I’m not saying DNA cases are easy, but they’re usually way less complex,” she said. “The investigation part of it is way less complex than a non-DNA case.”

Because of that, it can seem like the unit slowed down, she acknowledged. “But that’s not actually the case … we are hard at work.”

Udashen said DNA testing is now a routine matter before trial. Most conviction integrity work is non-DNA cases. Those are “more difficult cases,” he said.

“Most cases don’t have biological evidence,” Possley said. “Over time, DNA became much more valuable as a pre-trial investigative tool as opposed to a post-conviction exoneration tool. You get more people who are, say, exonerated pre-trial.”

Martin Santillan was the first DNA exoneration since Watkins left office. His case was also one of the first DNA testing requests the unit received. Garza said the review was already underway when she joined the unit in 2010. Santillan had been convicted of the shooting death of Damond Wittman in 1998, and long maintained his innocence. Investigators found a bloody Dallas Stars jersey that matched the description of the shooter’s attire near the scene. One witness identified Santillan as the shooter and the other three did not.

“The results came in and it wasn’t anything that was helpful for the case, to move the needle,” she said of the DNA testing. In 2014, Santillan requested a new DNA test, but that too, “didn’t get us to where we needed to be.”

But then, in 2021, Santillan’s lawyers, working with the New Jersey-based innocence organization Centurion Ministries, requested testing under the newer kit.

“We tried it under the new kit and we got DNA that led us to information that allowed us to pursue the exoneration,” Garza said. He was exonerated this March.

The path to exoneration isn’t linear, and doesn’t always follow a formula—especially when it is a case where DNA isn’t the determining factor in guilt or innocence. How does the Dallas County CIU determine which cases it will take?

“I don’t think anybody in this country who runs a CIU will be able to answer that question with a single word or a simple sentence,” Garza said.

A case can arrive at the CIU in several ways. It can be a written request from the inmate or family member, a defense attorney hired by the inmate or from an innocence project, or from a referral from the Forensic Science Commission. They can also come from the office’s own appellate division when an inmate files a writ of habeas corpus challenging their case.

Once the case is in front of the team, they look at several things before determining if it merits further investigation.

“You’re looking for red flags—is this a single-witness ID, did it involve any science that has been challenged? Were jailhouse informants used?” Garza said. The team will also check to see if there is DNA or other forensic science that can help determine if the person was wrongfully convicted.

Those red flags can be obvious, or they can take some digging, Creuzot said.

“I’ve signed an exoneration on somebody who was not a DNA case, but the women admitted the reason she picked him out of a lineup was the police told her to go pick him out, and she did the same thing in court,” he said. “She admitted (later) that she had no idea if that was the person who did it.”

That red flag, he said, came because “a kind of junior lawyer working for an innocence project was looking at a file that we provided, and found some notes from the police that suggested that she did not identify him.”

In the case of Nicholson, who was exonerated in June 2022 after being convicted of burglary and sexual assault in 1982, the red flags were easy to spot. Creuzot said the prosecution did not put two officers on the stand who would have affirmed that Nicholson was not the man described by witnesses.

“It wasn’t even close—we’re talking about a 14-year-old versus a 30-something-year-old man, a nickname, a house, a place, and a random sighting, and it turns into, ‘OK, this person was picked out of lineups,’” Creuzot said. “But back then nothing was videotaped. There was no standard procedure about lineups.”

Nicholson’s alibi—he was at his wife’s funeral—was ignored, and he was convicted. Once a case is accepted, the team investigates, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it will lead to an exoneration.

“Sometimes you have more questions than you have answers,” Garza said. “Sometimes you do get the answer and the answer is they’re innocent, or you get the answer and the answer is they’re not innocent.”

From there, Texas requires that the defendant file the case, and if the DA’s office agrees, the case is presented to a trial court. The trial court can make a recommendation to the Court of Criminal Appeals, which reviews the entire case.

“It’s presented to the nine-judge court, and they make a determination on whether or not the case gets overturned,” Garza said.

In some states, district attorneys can overturn a case without going back through the court system. That’s not true of Texas. “We have these layers of litigation steps that we have to take.”

If the Court of Criminal Appeals overturns the case, it is sent back to the district attorney, who decides whether to dismiss the case on grounds of actual innocence, or retry the case, in the event that it was a wrongful conviction and not necessarily an exoneration.

In some cases, the CIU will work with organizations like the Innocence Project, Centurion Ministries, or other attorneys. The DA’s office often doesn’t have the manpower to analyze each case, Creuzot said. Sometimes, the collaboration comes after the partners have done the legwork.

Garza said she’s also keenly aware—as is her entire office—that for every exoneration, there’s a victim or victims who thought the case was settled.

“Behind every one of these cases, unless it’s truly a false accusation, there is a person who was truly victimized,” she said. “And those are very difficult situations to be in.”

Sometimes, they trust the system, she said. In the case of false identifications, there is often a feeling of guilt.

“When they’re the ones that pick the person out of the lineup, it’s like, ‘I did this to somebody, I took away their freedom,’” Garza said. “They feel so guilty for something that really ultimately wasn’t even their fault. It was an honest mistake.”

“I’ve heard of some people that refuse to believe it,” Creuzot added.

“You do have people that refuse to believe that they got it wrong, ‘everybody else is wrong and I’m right and I don’t care what DNA says, I know what I saw,’” Garza said.

Those conversations, she said, are “emotionally challenging” and “heartbreaking.”

“On the one hand, when the person gets exonerated everybody’s happy. But then you think of the victim and their family, and you know, where’s the victory in that for them?” she said. “It’s bittersweet.”

Both Creuzot and Garza said newer technology and better practices are making it less likely—but not impossible—that someone will be wrongfully convicted. Statements are taken and recorded on video, police officers wear body cameras, and lineup and identification procedures have changed.

The quality of public defenders has also improved in recent years, and jurors, Creuzot said, are more mindful about their jobs. “They’re more careful and less likely to just accept that the police said it, so even if it doesn’t make any sense, I’m just going to go with the police.”

That doesn’t mean it’s not possible for an innocent person to go to jail, all four said.

“There’s always going to be wrongful convictions because the system is not perfect,” Udashen said. “You’re dealing with human beings, with people who can make mistakes, or sometimes people that aren’t acting in good faith. So there’s always going to be wrongful convictions, but there’s been a lot of progress over the past 15 to 20 years…to where I feel confident we have fewer wrongful convictions coming through the courts now than we used to have.”

Which is why Garza and her team are still working, even if much of that work doesn’t generate the same headlines as it did a decade ago.

Author