Seven years ago, while I was reporting a story about how tiny Troy University became an unlikely incubator for Super Bowl-caliber pass rushers, a college teammate of DeMarcus Ware’s named Shelton Felton needed all of one word to encapsulate the sight of him to me.

Felton could have described his old friend as brawny or chiseled or jacked or swole or imposing or any number of other adjectives which would be true, if only so evocative. Instead, he chose a name.

RoboCop.

You can picture it now, can’t you, all the way up to the smooth dome. Were you to construct a pass rusher in a laboratory, be it from sinew or steel, you’d want him to look like Ware: six feet, four inches, and 260 pounds of muscle definition and fast-twitch fibers. He was sleek in the way luxury SUVs are, somehow bulky and angular at the same time. Not all of this was essential for doing his job well, per se; one of his contemporaries, Elvis Dumervil, cleared 100 sacks despite being built like an oak stump. Ware may well be getting inducted into the Hall of Fame tomorrow had he possessed a little less size or strength. He probably could have racked up many of those Cowboys-record 138.5 sacks, ninth-most in NFL history, while being a tick slower rounding the corner.

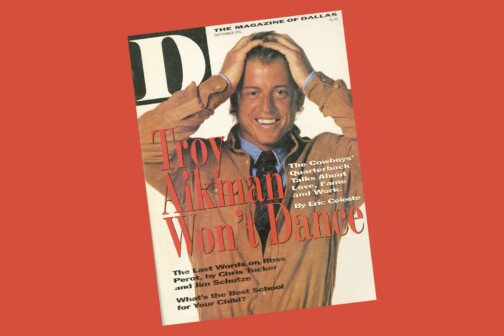

But there is something to be said for the Wares and Aikmans, the Dorsetts and Deions, the Larry Allens and Tyron Smiths: the gladiators whose every lunge or juke or punch or flick of the wrist reminds us that we are watching the physically aspirational come to life. It is among the most powerful allures sports have to offer: that we are the audience for the outer bounds of athletic potential.

Apart from a handful of years with Charles Haley, the Cowboys never employed a player quite like this on the edge before. This is one of Ware’s other great appeals—the immense satisfaction that came part and parcel with wondering how it would be to watch someone like that play for Dallas, and at last getting the answer.

Prior to him, Bob Lilly and Randy White were the alpha and omega of legendary Dallas defensive linemen: tackles who did their best work blowing through offensive linemen, not zipping around them. Ware was an altogether different experience; he ran down quarterbacks the way a cheetah would a possum. And he just so happened to arrive as football was irretrievably becoming a passing game. There was never a better time, in other words, for the Cowboys to at long last draft their answer to Reggie White, Bruce Smith, Lawrence Taylor, and Chris Doleman than exactly when Ware came along. Which means that the nine years he dazzled in Dallas could not have meant more, save for the possible exception of his bevy of highlights and All-Pro nods coming in an era when the Cowboys finally snapped their Super Bowl drought.

Not that this could have been any less his fault. For the bulk of his time as a Cowboy, Ware reigned alongside Jason Witten and L.P. Ladoceur, the unsung Canadian long snapper who executed flawlessly for 16 seasons, as the players you trusted most to do his job each Sunday. The genius of Witten was the reliability: how he moved the ball play after play, season after season, in such understated fashion that you barely noticed what he was doing until he ambled off the field soaked in sweat with a line of 11 receptions for 103 yards and a score. Like all great snappers, the genius of Ladoceur is you never noticed him at all. Ware’s genius was that of a showman, a stage performer. He monopolized your attention on every defensive snap because to take your eyes off him was to risk missing out on the moment you wouldn’t see anywhere else all day. The moments Cowboy fans had rarely seen until him.

If this feels blurrier in retrospect, that probably has something to do with Micah Parsons, his eventual heir, not only building on Ware’s legacy in Dallas but seemingly being poised to exceed it just two seasons into his NFL career. Ware at once dampens Parsons’ impact and burnishes it: he’s the only reason Parsons’ arrival doesn’t feel even more jarring in the lineage of Cowboys pass rushers, and yet the best possible compliment one can pay the 24-year-old is he sometimes does things even DeMarcus Ware never could.

Football is a brutal, unpredictable game, of course; there is no telling if Parsons remains this good or stays healthy or—not that anyone dares consider the idea—remains a Cowboy long enough to seize Ware’s mantle in the end. But if Parsons does, well, there is a reason no one forgot Lilly after White rose to prominence. Because just like Mr. Cowboy nearly a half-century before him, Ware became the prototype for a Dallas Cowboy at his position: how one should play and move and look and, above all, dominate. That the franchise lucked into a second one less than a decade after (foolishly) releasing the first does not, in any way, diminish the 55 years of trying and mostly failing it took to stumble onto the original.

The perfect player—the perfect fit—cannot be designed or conjured up on a whim, after all. DeMarcus Ware just made it look that way.

Author