Did you hear the one about the high school teacher who greeted his students the first day of school by asking, “If there are any morons in this room, please stand up?” After a slight pause, one youngster stood up. “Do you consider yourself a moron?” the teacher asked. “Not really,” answered the boy. “I just felt sorry for you standing up there all alone.”

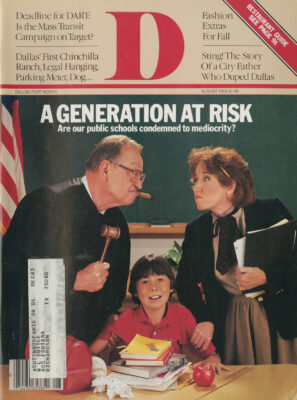

That’s just about what our view of public school teaching has come to now: a joke. Those who can’t, teach. Those who can’t teach, teach teachers. Meanwhile, a generation of kids is laughing all the way to the bottom of its class.

Teachers have been blamed for much of the mediocrity found in our schools. But have we been unfair? Sure, there are DISD teachers who can’t write a legible sentence on the blackboard. And incompetence cannot continue to be tolerated. It’s arguable, though, that the vast majority of our teachers are reasonably bright, potentially dedicated people capable of running a classroom where learning occurs. But most of them feel thwarted by an unwieldy bureaucracy, frustrated by indifferent kids and pressured by a district desperate to improve its image. And the vast majority of the public-us-couldn’t give a damn.

A funny thing happened on the way to the classroom: We lost respect for the teacher. Back in the days when Dad shared a pair of shoes with his brother and walked five miles to school in the snow, teachers were considered to be a pretty talented lot. Elevated by a mixture of fear and awe, the teacher loomed large over his young charges-and over their parents, as well. The teacher held the clues to a complex world. And in return for his generous gifts of mind, he received respect.

Many changes have occurred within the educational system since those one-room-schoolhouse days-including a fundamental rethinking of education. Dr. Louise Cowan, a teacher and a fellow of the Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture, says: “Right after World War I, a belief that education should be utilitarian-that it should teach people how to make a living-took hold. And once you decide that a person ought to learn a certain specialty-say, work with his hands or pursue a certain career-the teacher becomes less important. He is not imparting wisdom, but simply guiding in the acquisition of skills.” But Cowan doesn’t call for abolishing courses that prepare a child for his adult roles in life. “The question is when,” she says, “and the question is, how do we first awaken that human being with the ideas and values of civilization?”

There’s no doubt that the pendulum of public opinion is swinging toward more traditional fields of study: language arts, social studies, science, math. But it seems to be stuck in its perception of teaching as a lowbrow task. On a ladder that ostensibly exists to support education, the teacher occupies one of the bottom rungs. Teacher salaries are-and have always been- among the lowest in professional careers. Says middle school teacher Michael Brock-way, “In the eyes of the media and the public, we’re almost blue-collar workers.”

LINDA MITCHELL has one of those gifted minds that the DISD is turning cartwheels to attract. A Phi Beta Kappa, 4.0 math major and graduate of SMU, Mitchell has spent 11 years teaching math in an all-black high school. She’s on the verge of quitting.

Mitchell admits she’s been a thorn in her principal’s side-questioning policies, pushing for reforms. But she’s also played on the team – volunteering for textbook reviews, writing standards for math curricula, evaluating outstanding teachers for awards. She’s been threatened with open switchblades, hassled by roving neighborhood gangs and left to fend for herself by school security personnel. But those days are gone. What’s beaten Mitchell down are the Catch-22s of DISD. Like spending thousands of dollars nationwide to recruit math teachers and not caring enough to keep and nurture the ones they have. Like offering promotions, then never explaining why the transfer was blocked. Like perpetuating a system that rewards sloppy teaching at the same time it is trying desperately to improve instruction.

The hue and cry has been that the teachers can’t teach. But are they the cause or the effect of an educational system burdened by declining enrollments, declining test scores and declining esteem? No one component in DISD is blameless for its failings, and no one is fully to blame. For that matter, society as a whole is culpable for many of its educational ills. Family breakdowns, a poor economy, loosening moral structures, civil rights -all have contributed to a climate adverse to teaching “the way we were taught.” Disillusionment with post-desegregation performance has sent many families heading for refuge in the more comprehensible private or suburban schools – widening the rift between the “haves” and the “have-nots.” A prejudice has developed against the public school system at large.

Without really applying ourselves to the subject, we have accepted charges in the press and elsewhere that incompetence is the rule. But interviews with a number of DISD employees indicate that the problem lies not with the teachers, but with the teaching process as it exists within the district.

“I’m amazed at how many good teachers there are in our school system,” says one veteran whose teaching has consistently been judged outstanding. “In every school, there are one or two who couldn’t pass a minimum competency exam. Then there might be a handful more whom you would have to call ’poor.’ But beyond that are legions of decent instructors, among whom there is another handful of shining stars.”

“If we say that all students can learn, then we must also say that all teachers can teach,” says Cowan. “Teachers don’t have to be intellectual giants; teaching and learning are natural to the human species. By and large, even now, the person who chooses teaching as a vocation wants to teach, is intelligent enough to fulfill that role and is capable enough to do so well. I think it’s cruel to keep saying that the bottom one-fourth are the only ones going into teaching. That isn’t going to get us anywhere. We have to work with that desire they have.”

“The only reason anyone has ever gone into teaching is that they love kids and they love teaching,” says second-grade bilingual teacher Sandra De La Cruz. But even the most dedicated among the DISD ranks are embittered over what they describe as bureaucratic harassment and bungling. Theirs is a litany of protests: unfair practices, undue pressure, unnecessary paper work, incompetent supervision.

To illustrate that point, Mitchell details a story of a football player in her senior Fundamentals of Math class. When she failed him for the first six weeks of the year, she was summoned to a meeting with the student, his parents, the principal, the dean of instruction and the football coach. “I explained that I devised a simple test of minimum competency that all my kids had to be able to pass,” Mitchell says. “For the first six weeks, it was, ’Know your addition facts up to nine plus nine,” plus two other things that any fifth-grader should know. Remember – this is a senior in high school. He didn’t pass, so I gave him an F. The second six weeks, he failed because he couldn’t multiply up to nine times nine. At the end of the year, I was accused by the dean of instruction of hindering the boy’s future by standing in the way of his graduation. He had never had a passing mark in math. They insisted that I devise a special pass-fail exam. He failed. And they graduated him anyway.”

Policy zigzags -or the bending of rules to suit the occasion – grate at the morale of teachers who say they are trying to enforce reforms. “There’s a knee-jerk attitude on the part of DISD administrators,” Hiscox says. “They’re so concerned with saving face that they’re their own worst enemy.”

An example is the Basic Objectives Assessment Test (BOAT), introduced several years ago as a local competency exam slated to become a prerequisite to graduation. “Teachers loved the BOAT,” Mitchell says. “They saw the spark of motivation in kids who had never before seen a tangible reason to work. They saw kids turned on by the idea that they had to pass this test or they wouldn’t get out. But what happened? So many kids failed the test, they discontinued it. Instead of addressing the underlying problems that caused the students to fail, they stopped giving the test.”

DISD spokesman Rodney Davis says that the BOAT was discontinued because it was a redundant version of the state test, Texas Assessment of Basic Skills (TABS) – not because it reflected poorly on the district’s image. Whatever the reason, teachers point to the issue as one in a laundry list of policy revisions that have plagued DISD for the past decade.

“Every fall, there’s a new gimmick,” Mitchell says. “I guess this year it will be merit pay. So much time and energy goes into dealing with administration, there’s barely enough time to teach.”

“There’s not enough time to teach,” and “Just give us time with the kids” are refrains that are heard over and over again. Teachers complain about frequent interruptions over the public-address system. They question the validity of “pull-out” programs that take away from students’ regular instruction time. They resent the mountains of paper work that have become part of the daily routine. They’re insulted by demeaning staff-development sessions -“like hearing for two and a half hours how to correctly mark the grade book.”

Linus Wright has heard their cries, and he has answered by making “more time on task” (educationese for more teaching) a priority. Cutting paper work to a reasonable minimum is part of the plan. “There are lesson plans, transfer forms, ratio plans, nurse’s forms, report cards, attendance forms and special projects forms,” says De La Cruz. “Plus census forms, principal referral forms, test booklets, grade books and student files. If you think one of your students might need special ed, that’s another 20 forms. Then there was the form we had to fill out so the district could measure how many forms we had to fill out.”

The count topped out at a whopping 6,000 forms – most of which, according to DISD’s Davis, were redundant. A computerized process to consolidate information on fewer slips of paper is now under way, “but it will take time,” he says.

A simple axiom that turned up in discussions about paper work with teachers at various schools proved to be a common theme throughout: The same policies can be translated as positive or negative by a principal who is perceived to be either strong or weak. As one teacher put it, “In this district, they’re either for ya or agin’ ya.”

For example, Demetra Michalopulos (“Ms. Mike”) is a second-grade teacher at Preston Hollow Elementary School, which is generally considered to be a well-run school. When asked about paper work, she said: “What paper work? Teachers have always kept files on students, recorded grades and turned in lesson plans. That’s part of teaching.” On menial staff-development sessions: “Our principal doesn’t waste our time.”

By contrast, even something as basic as turning in grades can cause friction in a school where the principal and the teachers are at each others’ throats. For example, at one high school (where, incidentally, the principal is on probation), grades are due at midday on the last day of the six-week period – despite a district practice that gives teachers at least until 9 a.m. the day after. Says one of the school’s teachers: “There’s no way to get your grades in on time unless you stop teaching before the period ends and test the kids early. So a lot of teachers do. I happen to think that a kid deserves six weeks of instruction before he is evaluated. But the principal says that it would be too hard on the clerk who has to record the grades. It seems that most of our procedures are for the convenience of clerks. Who cares if the kid only has five weeks to learn the material, or if the teacher stays up all night grading the tests?”

And there are accusations of unfair hiring practices – of brand-new teachers get ting the plum positions over veterans who ask for them first. There are reports of patronizing step-by-step teaching aids: “Go to the map. Pull it down. Point to the continent of North America.” Of principals who can never be instructional leaders because they are former coaches. Of divisive racial infighting that pits black and brown against white.

“Every issue in our school comes down to black and white,” Mitchell says. “It’s not really teachers against teachers. It’s the principal’s attempt to turn us against one another and get the blacks to side with him.”

Peer victimization is one of the rampant ills identified by Cowan as endemic to the schools’ downward slide. “Because the system doesn’t support spirited, dedicated teaching, the good teachers are victimized. Those who aspire to a lesser standard can resent those who aim high. In other fields, the courageous, selfless worker may meet with peer resentment, but will have a measure of protection from above. In teaching, there’s no protection on either side.”

It may be that far from being protective, administrators have actually contributed to the teachers’ poor standing. Perhaps they’ve been locked in a classic management/worker struggle that other professions have managed to avoid. Certainly, we’ve found no dearth of administrators willing to freely bad-mouth teachers. One administrator, who was in charge of a program to identify outstanding teachers, sneered at the notion that the DISD contains more than a few worthy of praise.

If non-supportive administrators have hurt the teachers’ cause, antagonistic principals have all but destroyed it. The role of the principal is a crucial one. It is he who establishes the environment as either peaceful or chaotic, cooperative or combative, enthusiastic or lackadaisical. “The bottom line of why Preston Hollow works is that there’s a spirit of mutual respect among the faculty,” Michalopulos says. “Our principal, Dr. Vandygriff, makes his own decisions, but he always seeks our input first. We’re like a family – a racially balanced family.”

“Time and again, studies have shown that in schools where there is a strong principal-one who sets high standards for his kids, who supports his teachers, who roams the halls calling the kids by name – there is ongoing success,” Rodney Davis says. Darcie Sague, a teacher at City Park Elementary, puts it another way: “When the fish stinks, it stinks from the head down.”

If teachers have suffered at the hands of a system that is pitted against them, they are by no means alone. The real victims of the educational crisis are the kids. Less-advantaged students have been trapped in a maze for so long that they probably will never find their way out. Until these students get through the upper grades, the system will show only meager signs of improvement.

Why can’t teachers teach? Hear Jim Capizzi, an eighth-grade history teacher at Boude Storey Middle School in East Oak Cliff: “There’s no way I can teach history the way you and I were taught. In any given class of 25, maybe five of my students will be able to read the book. The others have reading skills that range between third- and fifth-grade level. It takes a full week to cover two pages in the text, and most of that time is spent on vocabulary and comprehension.

“But the fact that I’m teaching anything at all is a real improvement over my first year. I came to DISD after 10 years of teaching in New York, where I had always been the type to walk around the room, motioning and interacting with the kids as I talked. Well, I tried that here, and the room went wild. Finally, one girl came up after school and said, ’Mr. Capizzi, can I give you some advice? Why don’t you sit at your desk to teach?’ I tried it and a calm settled over the class that lasted until the last day of school. The teacher at his desk is a symbol of authority to these kids. And though it went against everything I had ever learned about what makes a good teacher, it was the only way I could be heard.”

“My kids aren’t belligerent or rude or doped-out or dangerous or any of those things you associate with the early Seventies,” Mitchell says. “In fact, they’re really sweet and enjoyable. They just lack self-control, and they aren’t motivated to learn.” Even the brightest students rarely turn in their homework or bring their books to class, she says. And part of the problem is that they lack the impetus from home to really apply themselves. “I’ll never forget one evening at our school when the teachers hosted an open house. We set up examples of the students’ work in the cafeteria and waited for the parents to come and look. Not a single soul passed through the doors.”

“Students aren’t afraid of failing the way our generation was,” Capizzi says. “You give them an F? They just shrug. I once spent five weeks teaching a unit on the Civil War. At the end of it, I gave a test; the last question was ’The South won the Civil War. True or False?’ One-third of the class put ’True.’ “

Discipline, in many schools, is still a major time-consumer. “Most of the students are fairly well-behaved,” Brockway says. “But it’s that 2 or 3 percent that can totally ruin class for the others.” In the high schools, perpetual offenders can be transferred out to a special “Metro” school. “But one of the problems in middle school,” Brockway says, “is that there’s no place for the disruptive kids to go.”

How to handle discipline problems is another of those thorny issues that Wright is attempting to grapple with. Until recently, there was no ironclad, codified policy that could be enforced throughout the schools. A student at W.T. White High School might be suspended for using obscene language in class, while the same offense at Madison might result in a mere “talking-to.”

“Not only is there no consistency, but the same pressure we get not to fail students is exerted in discipline problems, too,” Mitchell says. “Imagine trying to explain algebra while two or three students blithely roam around your room. It’s totally disruptive. But if I sent a kid to the office for wandering around, the principal would laugh in my face.”

Obviously, some principals rule with a fiimer hand. Others have tended toward leniency out of a fear of irate reprisals – legal and otherwise. Once there is a strict code established to fall back on, discipline measures should be easier for teachers to enforce.

In any field there are inequities, injustices, incompetence. But public education has fallen into an overwhelmingly complex mire. As one administrator says, “In a system as large and as diverse as DISD, anything that can go wrong will go wrong on any given day.” The one ray of hope is the groundswell of concern that is mounting in this country – from the president on down. Positive changes are in the works: tougher standards, higher teacher pay, fairer evaluations, more “time on task.”

In an essay on teachers, Louise Cowanwrites, “To embitter teachers or causethem to lose heart is to damage the instrument right at its cutting edge, where theenterprise can either achieve or fail toachieve its purpose.” What we must workon now is improving the environment inwhich teachers must teach. And thatmeans believing in teachers who are dedicated and encouraging those who wouldlike to be.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Restaurants & Bars

Some of Your Favorite Bars Pour This New Dallas-Based Mezcal

Racho is a mezcal five years in the making—and a collaboration between three Dallasites and a mezcalero from San Dionisio Ocotepec, Oaxaca.

Media

Brian Reinhart Explains to Slate Why Jalapeños Have Lost Their Fire

Our dining critic stars in a new episode of the podcast Decoder Ring.

By Tim Rogers

Baseball

How Clayton Kershaw Made the Senior Year Leap

An excerpt from the new book The Last of His Kind: Clayton Kershaw and the Burden of Greatness.

By Andy McCullough