SENATOR LLOYD Bentsen, weary from a long day of speechmaking in East Texas, eased into the narrow seat of the twin-engine private plane and fastened his seat belt. His wife, B.A., took a seat facing him and did the same.

As the pilots revved the engines and aimed the aircraft down the darkened runway, the Bentsens leaned forward and clasped hands. Only when the plane was safely off the ground did they relax their grips and settle back into their seats.

As the small plane turned away from Texar-kana, illuminated by the starry spring sky, and began its one-and-a-half-hour flight to Austin, an aide poured white wine into plastic cups. Another passenger asked Bentsen, a former bomber pilot, about the hand-clasping ritual, if he was afraid of flying.

“No,” he replied. “It’s just something we started doing after a small plane we were in made a crash landing about 25 miles west of Houston in 1964. We were on our way back from Kerr-ville. It was about this time of night, 10:30, and we developed engine trouble. The pilot decided to set it down in a field. It was a close call. We were lucky.”

Bentsen and his wife will repeat their small ritual of luck hundreds of times this summer and fall as they crisscross the Lone Star state in quest of a third six-year Senate term.

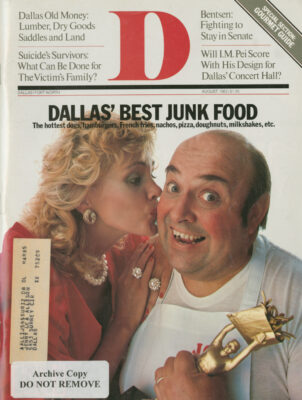

At 61, Bentsen, a Democrat, appears content to finish his political career in the Senate, even though he once thought himself bound for the presidency. Now Bentsen, whose low-key manner and quiet reserve are often mistaken for aloofness, faces a tough reelection challenge from Dallas Congressman Jim Collins, whose persistent campaign against “Liberal Lloyd” has vexed the senator and his supporters.

“Liberal Lloyd” is probably a misnomer, but it may well be that Bentsen is the last of his kind: those powerful, pragmatic business-oriented Texas Democrats who knew how to follow Lyndon Johnson’s advice to “be as liberal as you can without fouling your financial nest.” Which really meant: Be as national as you can without losing your home base. Collins senses that Bentsen is vulnerable on this score.

After 11 years in the Senate and an ill-fated presidential bid in 1976, Bentsen is still a political mystery man-respected by those who know him, but lacking the forceful personality and charisma that have brought national fame to many of his colleagues. Although Bentsen has held office in the state since 1971, motel clerks and dinner organizers still misspell his last name.

On a recent trip, signboards in hotel lobbies from Nacogdoches to Austin were lettered with the name “Bentson” or “Ben-sen.” A dinner program in New Boston misspelled the senator’s first name as well as his last name. A traveling aide has a sharp eye for spotting such embarrassments and is adept at persuading hotel bellmen to make appropriate spelling changes before the senator sees the errors.

Bentsen has always had an image problem. His unruffled manner sometimes makes people who don’t know him uneasy. His well-tailored appearance, perfectly shined shoes, distinguished gray hair and well-tanned face bespeak intelligence, wealth and power. But his natural reserve and soft-spoken, quiet demeanor are sometimes misunderstood by those who don’t know him.

The perceived aloofness is, in fact, a careful brand of caution. He slowly measures his words, and waiting for him to answer a question in an interview is sometimes like waiting for Jack Nicklaus to putt.

But Bentsen is the ultimate gentleman – unfailingly polite, thoughtful and considerate. At a “town hall” meeting in Crockett this spring, he was obviously uncomfortable in the stuffy motel banquet room where he was speaking to constituents. The senator, formal as always, asked a favor of his East Texas audience. “Can I take off my coat?” he said in the polite manner of a schoolboy asking to be excused for a minor transgression. “Would you all mind?”

After carefully hanging his suit coat on the back of a chair, Bentsen continued answering questions about Social Security, the budget and President Reagan’s proposed “new federalism.” He did not roll up the French cuffs of his blue-striped shirt with the small “LMB” monogram on the pocket, nor did he loosen his tie.

Several days later, Bentsen was asked about his patrician image.

“I’m not the typical back-slapping politician,” he said. “That’s not my nature. Most people who see me that way [as aloof] haven’t seen me down in the barrios. They haven’t seen me on the ranch or at the farm. I’ve always been one who, in spite of being a very quiet person, likes to do new, challenging things.”

Friends call him brilliant, shrewd and fiercely competitive. Whether it be in politics, business or sports, he hates to lose. This aspect of his personality surfaces on the tennis court, which he usually visits twice a week to keep his weight at 173 pounds-trim for his 6-foot 1-inch frame. Bentsen prefers the more strenuous singles game to doubles and enjoys playing with FBI director William Webster or Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens.

During one match at his private club in Arlington, Virginia, where Bentsen plays at six in the morning, he crashed into a fence going after a ball. “Must be Bentsen,” said a player on an adjoining court.

Political analysts have a difficult time wedging him into a typical Texas mold. He just won’t fit. Bentsen doesn’t have Bob Strauss’ magnetic personality; there’s no good-ol’-boying in his repertoire. When Bentsen speaks, his oratory doesn’t jolt people from their seats the way his onetime close friend John Connally’s does. Nor does Bentsen shoot from the hip like Gov. Bill Clements.

In the heat of a tough budget battle, it will be College Station Democrat Phil Gramm’s visage, not Bentsen’s, coming into your living room on the network news. Bentsen doesn’t spin yarns in a twang dripping West Texas like Representative Kent Hance of Lubbock. In fact, Bentsen’s voice bears no trace of his South Texas upbringing.

Indeed, many Washington insiders respect Bentsen as a solid legislator, a shrewd tactician, a savvy politico and a compassionate man who lends the Texas congressional delegation elegance and class. Jack Albertine, who was executive director of the Joint Economic Committee when Bentsen was chairman, praises his analytical mind, his feel for the legislative process and his good sense of people. “It’s a dynamite combination,” Albertine said. “He’s the coolest guy I know. I’ve never seen him sweat. His basic personality is reserved, but it has nothing to do with his character or ability.”

Austin political consultant George Christian, who has known and worked for Bentsen for more than a decade, says people don’t really know or appreciate how knowledgeable Bentsen is. “He’s hidden his light under a bushel,” Christian said. “He doesn’t have the pizazz of a Jack Kemp [Republican congressman from Buffalo, New York], who has done a much better job of selling and promoting his economic ideas.”

“He’s not flashy, not dramatic,” said Loyd Hackler, Bentsen’s first administrative assistant, who now lobbies for the American Retail Federation in Washington. “His success is due to his logic, his effort, intellect and spirit. He’s a tough S.O.B.”

Lloyd Millard Bentsen Jr. has always been well-off, due to his family’s tradition of persistence and hard work. His father’s family, Danish immigrants, moved to the Rio Grande Valley from South Dakota, attracted by the fertile soil and long growing season. The Bentsens thrived in South Texas. Lloyd Bentsen Sr. and his brother Elmer made several million dollars buying land and selling it to Midwesterners seeking warmer climes.

“My father was a man who worked incredibly long hours,” Bentsen recalled recently, “which meant he didn’t get to spend much time with us growing up. But that time he did spend with us, the quality of the time was exceedingly high. He took us [Lloyd and his brother] on hunting trips where there was no competition for either his attention or our attention. Those were times that we as boys treasured.” His 88-year-old father still lives in McAllen.

Bentsen’s character, however, was solidly shaped by his mother. Dolly, who died several years ago, instilled self-confidence in her sons. “She told us that we could reach such goals as we sought, if we would really apply ourselves,” Bentsen said, “and she worked on us to excel.”

Bentsen still feels strong affection for the rugged Valley ranch country where “something either bites you or scratches you or sticks you; but it also has its attraction, and you always come back to it.”

He was born in a small frame house by the side of the Edinburg Canal in McAllen. He went to a country school. Many of his playmates were Mexican-Americans, who were either farmhands or farmers, and he learned to speak Spanish soon after he was forming his first English words.

Despite his moderate-to-conservative voting record, Bentsen always has had the solid backing of Texas’ Mexican-American community and has been a proponent of civil rights. He believes his South Texas upbringing gave him a greater understanding of Hispanic issues.

“That’s where I got my interest in things like the Voting Rights Act,” he said. As a young congressman in the Fifties, Bentsen was one of only two Texas representatives who voted to repeal the poll tax, a seemingly insignificant position by today’s standards, but a rather brave one then.

After graduating from high school at 15, Bentsen entered the University of Texas, completed his law degree and joined the Army. At 23, Major Bentsen was in flight training and ended his military career as a B-24 squadron commander in the Army Air Corps. He flew 50 missions over Europe, was shot down twice and won the Distinguished Flying Cross. (Bentsen gave up flying when he first was elected to the Senate in 1970 because he didn’t have enough time to maintain his instrument rating. He hasn’t piloted a plane for years. He demands that two pilots be on all private planes he uses for campaigning or other travel.)

While he was in the Army, Bentsen married Beryl Ann Longino of Lufkin, whom he met while they were students at UT. Although they knew each other in Austin, they didn’t start dating until after he had left school and was in the Army. Bentsen was in New York on his way to combat intelligence school. “I remembered that this beautiful girl I had met [the tall and striking B.A. Longino was working as a model for such well-known chronicles of high fashion as Vogue and Mademoiselle] was living in New York City, and she had an unusual last name,” Bentsen said. “I thought I could find it in the phone book.” Because he had only a couple of hours in the city before his train left, Bentsen called B.A. at 6:30 a.m. and asked her to have breakfast with him. That breakfast date was the beginning of a lifelong-and valuable-partnership.

Six dates later, B.A. Longino and Lloyd Bentsen were married in Columbus, Mississippi, where he was taking Air Force flight training.

The day before the big event, the U.S. Army put a wrench into the wedding plans -Bentsen was ordered to have two wisdom teeth pulled. That night, at a movie, he began hemorrhaging and had to go to the base hospital.

The bleeding stopped the next day, and Bentsen called his bride-to-be from the hospital to assure her that he would be there for the ceremony. “So when The Wedding March started, 1 didn’t show up and B.A. didn’t know what had happened to me,” he said. “I guess I got excited, because I started hemorrhaging again.” Bentsen was determined not to let a little blood ruin his wedding day. The cool-headed Lloyd Bentsen took control. “I went out in the courtyard and I got a rock,” he said. “I put it down into that cavity, bit down on it and came back for the marriage ceremony mumbling my ’I do’s.’ “

B.A. has been at Bentsen’s side throughout his political career, which began when he was elected county judge of Hidalgo County at the age of 25, the youngest county judge in Texas.

Two years later, Bentsen topped that by becoming the youngest member of the U.S. House of Representatives, where he quickly impressed crusty old Sam Ray-burn, Speaker of the House. Rayburn, a native of Bonham, thought enough of the freshman congressman from the Valley to invite him into his inner circle, better known as Mr. Sam’s Board of Education.

Once, when Bentsen and “Mr. Sam” were sharing ideas in the Speaker’s Capitol hideaway, a photographer brought in a portrait of Rayburn. The Speaker didn’t think the photograph, which showed him with a stern look on his rugged face and highlighted his gleaming bald head, was very flattering, and he pitched it into a wastebasket. Bentsen retrieved it and asked Rayburn to sign it.

The photo, inscribed, “To my friend Lloyd Bentsen, who likes ugly things,” hangs in Bentsen’s Senate office. It dominates the surrounding photos of Dwight Eisenhower (whom Bentsen tried to persuade to run for president as a Democrat), Harry Truman (who at one time inhabited Bentsen’s Russell Building office), Lyndon B. Johnson, John F. Kennedy, Jimmy Carter, Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan.

Bentsen’s career in the House was punctuated largely by his interest in public works and veterans’ affairs. He did not strongly oppose civil rights legislation and gained widespread publicity in 1950 when he proposed that President Truman threaten to drop the atom bomb on North Korea if the country did not withdraw its troops from the south.

A new documentary film about the atom bomb, The Atomic Café, includes newsreel footage of Bentsen standing on the steps of the Capitol, voicing his pro-nuclear stance. Bentsen, who years later in the Senate voted against bombing Cambodia, now says of the speech, “I was a lot younger-and the world was a lot different – when I said that 22 years ago. I am a lot wiser today.”

After serving three terms in the House, Bentsen decided not to seek reelection, a decision that Rayburn didn’t understand. “Sam Rayburn said I was doing a very foolish thing,” Bentsen recalled. “He told me I came from a safe district, and that in another 25 years, I could be Speaker of the House. That seemed like forever to me. I didn’t want to spend all my life up there.”

But Bentsen didn’t believe he could support his family on the $12,500 congressmen were paid then, and he went back to Texas. Bentsen briefly considered running for the Senate in 1952 and 1964 and for governor in 1954, but always gave up the idea because he believed he could not afford it. He decided, finally, that he would not return to public service until he was financially independent. For the next 16 years, he concentrated on making money. And, as usual, he was very successful.

After considering several Texas cities in which to base his business ventures, Bentsen landed in Houston. It was a growing city and, he said, the leadership was looking for young people to participate in the economic boom taking place there.

“You go to a place like Cincinnati,” he said, “and you make a bad investment, and you have made a bad investment. You go to a city like Dallas or Houston, and you make a bad investment, and time will often take care of it for you.”

Bentsen chartered a new insurance company, Consolidated American Life, which he built into an empire that was traded in part in 1972 in a $30-million deal. As his business grew, Bentsen attained the financial independence he wanted and again turned his attention to public service.

In 1970, after 16 years in the private sector, where he increased his financial empire as well as his understanding of how the economic system works, Bentsen re-entered politics.

“I think public service is a high calling, just like teaching, preaching or healing; and I think I have a capacity tor public service and a capability for it,” he said.

No one in Bentsen’s family had ever shown an interest in politics. When asked what drew him to that world, the senator hesitated. “Well, it sounds too square,” he said. “But I always felt I could have an influence on where this country went, perhaps better it. After I’d been out for 16 years, I was financially secure. I enjoyed making money, but I wanted something more than that, and this is the center of the free world, and you ought to do what you’re best at.”

Conservative Democrats in Texas wanted to unseat Sen. Ralph Yarborough after Lyndon Johnson became president. But Johnson, seeking election to a full term in 1964, browbeat one candidate into withdrawing from a race against Yarborough and persuaded Bentsen not to make the challenge, either.

But six years later, Yarborough, who was 66 and had been in office since 1957, was ripe for defeat by the right conservative candidate.

Bentsen made his move and ran a campaign like he was chairman of the board. He won the Democratic nomination with 53 percent of the vote. He went on to defeat Republican candidate George Bush in the general election. In the 1970 Senate race, Texas voters had a choice of a Republican and a Democrat with essentially the same ideologies. Bush had planned his campaign strategy with a race against Yarborough in mind. Running against Bentsen in a state still dominated by the Democrats, Bush couldn’t overcome him.

One of those who helped Bentsen in that first Senate race was John Connally. Connally recently said he will campaign for Republican Collins, Bentsen’s opponent in the fall. Bentsen is not surprised. “We’re friends,” he said. “He’s just working the other side of the street.”

Bentsen is credited with helping get Connally’s political career rolling. In 1961, when Connally was secretary of the Navy during the Kennedy Administration, Bentsen called on him one day and urged him to return to Texas to run for governor. Connally demurred, saying he didn’t know where he would go to get his first campaign contribution. Bentsen pulled out his checkbook and said, “Use this.” But the two men drifted apart during 1974 and 1975, when Bentsen was preparing to run for president and Connally was under indictment for allegedly accepting a $10,000 bribe when he was Nixon’s secretary of the Treasury. Bentsen cuts short discussion of the subject, but former associates say a chasm developed between the two when Connally wanted Bentsen to appear at his trial as a character witness.

Bentsen advisers thought that would be unwise and suggested that Bentsen do so only if asked. “I was never asked,” Bent-sen insists. “Never. Not even an intimation.”

Connally was acquitted, and his relationship with Bentsen cooled. The two have made their peace, but associates of both men say the relationship isn’t what it once was.

As the junior senator from Texas (Republican John Tower was first elected to the Senate in 1960), Bentsen quickly learned the value of his Senate seat. Once again in Washington, it wasn’t long before he began thinking about higher office – the presidency.

Bentsen had accumulated more than $300,000 from fund-raisers in the state by the time he announced his candidacy on Washington’s birthday in 1975. In the wake of Watergate, prospects looked good for a Democratic candidate. Although several notables-including Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson of Washington, Rep. Morris Udall of Arizona and Gov. George Wallace of Alabama – had already entered the race, a change in delegate-selection procedures gave everyone a chance.

Bentsen hired Ben Palumbo of New Jersey to lead his presidential campaign. The strategy was to do well at precinct caucuses in Mississippi and Oklahoma before major primaries in New Hampshire and the South. Bentsen’s braintrust was counting on one crucial assumption-that no candidate would emerge from the primaries with enough delegates to win a first-ballot nomination.

But while Bentsen was focusing on Mississippi and Oklahoma, an unknown named Jimmy Carter was building a campaign in Iowa. Wallace got most of the regular Democrats in Mississippi, while Carter and Sargent Shriver picked up party loyalists. Moderates, whom Bentsen hoped would vote for him, either voted uncommitted or stayed home. The result was less than 2 percent of the vote, a disappointing showing in Mississippi. Bentsen was stunned and disheartened.

He skipped Iowa and concentrated on neighboring Oklahoma, but withdrew from the race on February 10 after another disappointing showing in the Sooner State. He left his name on the ballot for the Texas primary, but the campaign was over.

Ironically, Carter thought Bentsen would be his main opponent for the nomination. Carter told Washington, D.C., political reporter Jules Witcover as much after the campaign. “At the very beginning I thought it would be Bentsen,” Carter said. “He had a good start in New Jersey, Virginia, Oklahoma, Tennessee, South Carolina. But he didn’t have his heart in it. He didn’t make an all-out nationwide effort, and he faded.”

Reflecting on his try for the presidency, which he called “the ultimate responsibility,” Bentsen said he got into the race so late it was already over. “I didn’t go into New Hampshire and I didn’t go into Iowa. The problem is, you work all day in the Senate and go out on weekends and nobody’s there. Unfortunately, the system is set up now where the fellow that has the best chance is the fellow who is out of a job so he can devote full time to it, as Jimmy Carter did.”

His White House try quashed, Bentsen shifted his energy to winning reelection to the Senate the same year. He defeated a little-known Texas A&M economics professor, Phil Gramm, for the Democratic nomination, and beat Dallas Congressman Alan Steelman in the general election.

Back in office for another six years, Bentsen shifted his attention to economic issues, holding a seat on the Senate Finance Committee and becoming chairman of the Joint Economic Committee in 1979. His work on economic policies increased his visibility, and he is considered one of the nation’s leading economic experts.

“None of those things [defense and foreign policy, which offer a senator more visibility] work unless the economics of the nation are in good order,” he said. “You can’t improve the lot of people if they don’t have the opportunity for a step up in life. I think the greatest answer for social justice in this country is an expanding, growing economy, which provides opportunities.”

Bentsen believes government has an obligation to care for the very young and the very old. Rayburn, more than anyone, helped shape Bentsen’s political philosophy. “Sam Rayburn was a man who was always concerned for the people, and yet he also was a pragmatist. He was a fiscal conservative. But he also believed in working on self-help programs,” Bentsen said.

Although he supported President Reagan 70 percent of the time last year (compared to Collins’ 71 percent), Bentsen retains strong feelings for the Democratic party. “The Democratic party is more a party of the people,” he said, “but I’ve always thought it was a serious mistake to approach the major issues facing the country in a purely partisan way.”

Once again, he spoke of Rayburn. “He could be a partisan man, but he would also, in the big issues, work with the Republicans.”

In town hall meetings in East Texas this spring, Bentsen told audiences that the country did not have a Democratic economy or a Republican economy, but, rather, an American economy.

While some senators can’t resist grandstanding before the glow of television lights in Senate committee hearings, Bent-sen is not one to advance his own cause purely for publicity purposes.

For example, shortly after the Maya-guez incident in 1975, a network television correspondent assured Bentsen’s press secretary the senator would be on the evening news if he would go before the cameras and make a tough statement denouncing President Gerald Ford’s handling of the crisis. The press aide, recognizing an opportunity to get his boss some national attention, hammered out an appropriate statement and showed it to Bentsen. The senator read it, studied the words before him, and gave his assessment. “I’m sorry, but I’m not going to say that about Jerry Ford,” he told his press man.

The next day, Bentsen and the press secretary were having lunch with a veteran radio correspondent. During the conversation, the radio reporter told Bentsen he should never let his advisers push him into wild publicity stunts. “Don’t worry,” said the press secretary. “He won’t.” Bentsen laughed.

Bentsen stays on top of issues by working closely with his staff. Staff members say he is very demanding.

“If you bring him a memo on a piece of legislation, you’d better be able to defend it, now and 30 days from now,” one aide said.

Bentsen never displays his temper, but he makes it very clear when he is unhappy.

“He doesn’t raise his voice and scream and shout, but you know when he’s angry. If you’ve done a bad job, he tells you it’s a bad job. But it doesn’t linger and isn’t mentioned again,” a former aide said.

George Christian says Bentsen sometimes appears too analytical and has a tendency to talk over peoples’ heads, especially if the discussion concerns economic policy. “In the first Senate campaign in 1970, he’d talk to the campaign staff about things people didn’t really grasp,” Christian said. “He was always talking about the ’economic model’ or something. Nobody knew what he was talking about.”

In recent meetings with constituents back home, the discussion often turned to the economy. Bentsen sprinkled his remarks with “CIP,” “accelerated depreciation,” “interest-induced recession” and “monetary policy” without really explaining terms that could almost be seen sailing over the heads of his audience.

But Bentsen impressed his audiences with his authoritative recitation and even blended in a bit of well-received humor when he talked about the importance of inspecting new weapons systems to make sure the government is getting its money’s worth. “We’ve had a lot of problems with the M-l tank, so I went down to Fort Hood recently and told them 1 wanted to drive it,” Bentsen said. ” ’You want to drive it?’ they asked. ’Yes, I want to drive it. Show me how to get in.’ Well, they said it was sort of like getting on a horse, and I understood that. So, I got in, started it up and drove that tank up hills, down ravines, through water-and you know what I was thinking? Boy, if I just had this on the Houston freeways.”

He ended the meetings on an upbeat, patriotic note, citing America’s greatness.

“Eight of the last 10 Nobel prizes for science went to Americans,” he said. “Look at the dollars coming from the Middle East to invest in U.S. cities. Look at all the Mexicans who have condominiums at Padre Island. One-fourth of the people in the world are hungry and the best-selling book in the United States is how to lose weight.”

BY THE TIME Bentsen had finished his second plastic glass of white wine, his plane was making its approach to Austin’s Municipal Airport. Delays at the New Boston Chamber of Commerce dinner had set his schedule back nearly 45 minutes.

The day had been long and hard, starting with a breakfast meeting in Nacog-doches at seven, a speech before the Long-view Lions Club followed by a town hall meeting there, a reception for the press in Texarkana and then the dinner in New Boston.

A covey of aides was waiting for the senator and Mrs. Bentsen when the plane finally touched down shortly after 11:30. Bentsen climbed into the front seat of a staffer’s car for the short ride to the hotel, where the signboard in the lobby welcomed Senator “Bentson.”

He was too tired to notice, but by morning the sign had been changed to the proper spelling.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Home & Garden

Level Up Your Poolside Party Game This Summer With Four New Burger Recipes

Find exclusive recipes from the minds behind Burger Schmurger, Liberty Burger, Parigi, and Rodeo Goat.

By Lydia Brooks

Commercial Real Estate

What’s the Key to Attracting Talent? These Three Frisco Developments Offer Answers

A trio of projects featured at an inaugural development summit previewed what they’ll bring to the table for employers—and for the talent.

Literature

Ben Fountain Wins Major Award!

The 2024 Joyce Carol Oates Prize goes to Dallas' own.

By Tim Rogers