It is easy to get lost in the biography of Mark Bradford when looking at Mark Bradford’s art, on view in a new exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art. That is because Bradford puts it there. The artist’s story, growing up in Los Angeles, helping out in his mother’s hair salon in South Central, the textual debris of the street, the maps of his neighborhoods, his time in New Orleans: all of these things are made present in his paintings through the materials Bradford uses. But what is easily glossed over amidst all this politicized energy are the taboos the artist is addressing more directly — not necessarily social taboos, but taboos about abstract painting and art history. We spoke to Bradford about his work, development as an artist, and running up against the prickly norms of the art world.

FrontRow: I wanted to ask you about that moment around the Art Basel hair salon installation in 2002 and the transition out of using perm end papers in your work. How did you know – and what triggered your knowing – that is was time to move on? And how did you figure out what materials to move on to?

Mark Bradford: You start with the place you think is authentic. So I jumped into it, and I jumped into something that had some currency that I could hold on to. I think it comes from that my mother had a hair salon in all-black Los Angeles, but I grew up in all-white Santa Monica. So it is very natural for me to connect the two. But, the fallout: it’s not thinking about the fallout, which is very naïve. I’m just thinking, “This is interesting.” So I just started going along and started noticing that although my investigation was honest and came from an honest place, the writing was becoming so autobiographical and so much to do with me and my mother and hairdressing. But, I’m one of those people who, when I’m driving down the street, you don’t know where I’m going or if I’m lost because I drive the same. So I didn’t stop making work. That’s the thing: I didn’t stop. But I started to understand that I had created something that was becoming very quickly static and very much narrative and autobiographical. And I started to look at the history of that and people of color. “Hmmm,” right? The marketplace sort of supports that type of work so that people write about it.

So all these things come into play. But I was just like, “hmmm.” Not stopping working and not changing what I’m doing, but just an interior “hmmm.” Looking at what I’m doing, maybe stepping back from it, almost becoming a viewer of yourself. And it was really slow. I started seeking out other shows and other kinds of people. But this was very conscious. If I am going to change the discourse, then I’m going to have to change the different types of relationships that I’m having. I had to kind of go back, read other things, kind of put myself back into school again. I’m always putting myself back in grad school, like every two years. Like, “Whoops, time to go to grad school again!” I just don’t like, “this is my shtick and I just do it.” No, I’m constantly putting myself back in school. It was putting myself back in school, reading other material, being fascinated by other types of work. And the work kind of started to follow those kinds of interests. But the reaction was like, My God! You build yourself up as having this kind of collector base, sort of writing base, and then you change. It is like, “Oh, why did you do that?”

FR: In the context of this show, that gradual transition you are talking about, it all looks very direct and linear. Is there work here that you can point to as being a significant transition point?

MB: The first room. I remember putting those white lines because I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know how to connect space. The only way I knew how to connect space was with end papers. I’m just going to have to connect it with white lines. How do I go from here to here without an end paper? How do I do that? Later, it became no end papers and also no urban material, because that started to become a trap – the next trap. Okay, here we go, he doesn’t do end papers any more, but now he’s “urban.” The whole language around urbanity, the whole langugate around hip hop. You know, I’m a black male, but I’m not that at all. So it was like, oh, wait a minute, I have political, emotional problems with that. Now urbanness means blackness and a certain type of maleness. So here we go again. So it is constant. I think I’m always kind of aware that I want the conversation to keep moving, that I kind of constantly want to be asking myself questions, even though I now have to lead that in the glare of the spotlight, you know? I just have to pretend like it is not there.

FR: To a certain extent, though, when the maps are referencing specific neighborhoods, or New Orleans, or James Brown, those things are unavoidably politically charged. Is there any sense of provocation in that? Are you trying to play to the stereotype and then move away from the stereotype?

MB: It’s never provocative. I’m not a cutesy hood-and-wink person at all. I have an honest interest in that investigation. James Brown is Dead is perfect for me. I saw it on the cover of a magazine and boom! It was perfect. Yes, it was urban material. So what happens is the desire and the impulses are immediate and honest, and then sometimes you just have to deal with the context, because if the idea is good it is just good and you just kind of go with it. Sometimes you just have to deal with the context, and you have to deal with your ambivalence about that. And then other times you just break completely away. It is really like you can have this real desire for something or desire for a place, and the politics are really problematic. I still have an interest in pulling this stuff, so I’m not ambivalent about the impulse. But I can become ambivalent about the space that that sort of conversation goes on in. Some people talk quite a bit. I was not raised in South Central, but that’s talked about a lot. I was really raised in all-white Santa Monica, socially.

FR: The benefit, though, is that you also enjoy a freedom to explore abstraction in a way that isn’t as politically charged as, say, a white kid who grew up in the suburbs and then went to CalArts who starts making abstracts.

MB: How do you talk about mid-century abstraction anymore? It is like, are you kidding? Especially if you are white. Forget it. Goodbye. And especially if you are heterosexual. Better to talk about drag or something. I thought, oh, you know, urbanity, the city, I’m always fascinated by cities in general. I’m very much fascinated by public space, where everybody can go. I love things where everybody can go. I don’t like things that are exclusive. The art world is so exclusive. I make abstract paintings that have this outward looking thing that takes this stuff from the city, pulling this stuff from the city, the urban-ness, the South Central-ness. Maybe if I was doing it in Wichita, I don’t know if it would have been any different. It has afforded me a lot more space. It has afforded me to kind of push that dialogue further, to change the critique of abstraction, the feminist critique of it. I’ve read all the critiques of it, but I thought, well, I could have a different relationship to it. I can pack it in a different way, which I think is the most interesting thing that can happen now.

I think that this re-packing or taking the subject position or demanding a different view: I think that is what is interesting now. Everything’s all been done, but it hasn’t been done the same way from the same position. I wasn’t looking to do anything new or ironic; I was just looking for a real honest impulse and developing a new way so it felt like me.

FR: Who are looking at that’s doing that these days?

MB: I like Ruben Ochoa, very much. I like Matt Monahan. I like the guy who did the Argentine pavilion atVenice, Adrián Villar Rojas. But I hear more. I’m not really into this “hands off” thing. I don’t like when people tell me “hands off.” So I think that I just went to that place that’s “hands off” and decided what it is going to be for me. I said, “Guys, I need to change based on my own thing.” It’s not the market; it’s not my dealer. You know, I really feel like I just got out of art school. I mean, really. I mean all these people’s words, and these people show up. Literally, I feel like I just got out of school. It’s crazy. It’s always, “he’s a nice guy.” It is not that I’m a nice guy; it’s that I’m so available because I’m, like, right here. I didn’t change. It doesn’t change. It does not change. I don’t think I’m ever going to reach that thing. I’m right there, I’m right in it. I like artists, but what does not make me feel good is seamlessness. “Let me show you my slides, they are perfect. It was at this big museum. Clearly I’m successful. Here’s my . . .” I’m like, whoa! What is that? I need some unsurity, “I’m not sure,” “I’m working this out.” “This worked, this didn’t.”

FR: Vulnerability

MB: Yeah. Then I feel okay. But when I don’t understand half of what they say. You know this kind of world that we play with? Especially in post modernism, where language is used as the weapon to alienate and all of the hierarchical relationships to education. Where did you go to school? I will know in five minutes if you say “story” instead of “trajectory.” I will place you in a certain place, because you didn’t have a theoretically education, you had a modernist education. We do that a lot in the art world – big time. And I don’t want to do that.

FR: And you found a way to be part of it, and yet not part of it. Is it a constant balancing act?

MB: Yeah, I’m in, but I’m just not doing that. Exclusion? I’ve had enough of that growing up, not being invited to the party, not being the guy. I’ve had enough of that. I didn’t get into this for that, to be at the cool table.

FR: There’s a lot of that when you come to town with a museum show. Do you enjoy this sort of thing?

MB: I enjoy blasting at a party and being really regular and watching people go “ooo” That part I love. “Nah, I wasn’t thinking about that at all, I was totally stressed out.” That part I enjoy.

FR: The mystique that is built up around you deflates.

MB: I like that part, just breaking it apart.

FR: Do people get disappointed or shocked?

MB: Just kind of shocked. Or some art people are like, “Don’t talk like that; you’re giving away.” For me, it’s the only way I know how to be. I don’t want this, how I got here, to be this huge mystique. These are the things that I do; these are the things that I take. I’m not savvy. I didn’t have an army of curators behind me that strategically – no. So not at all. I just do what I do and figure out what makes sense for me. Even when I got out of Cal Arts, I moved away from the whole mechanism and moved to a whole new part of the city because I knew that I was going to be doing work that wasn’t going to be cool. I could kind of tinker in my own.

FR: Was there fear that you wouldn’t be able to find the right gallery?

MB: Not the gallery. You have to understand that Southern California runs on a postmodern engine: CalArts down. It’s a theoretical engine, all the art schools, institutional critique, it’s conceptual. So that is the “god.” I’m just over here twiddling with material. So you’re like nervous. “I’m not going to have a career, I know!” “I’m not going to be smart, I know!”

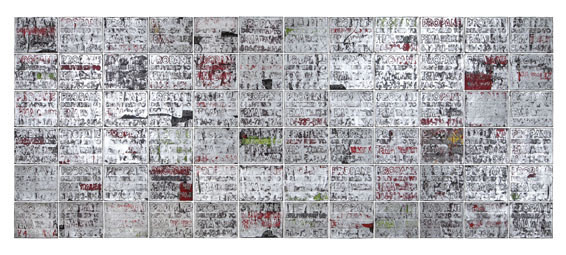

Image at top: Corner of Desire and Piety, 2008. Acrylic gel medium, cardboard paper, caulking, silkscreen ink, acrylic paint, and additional mixed media; 135-3/4 x 344-1/4 inches. The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica © Mark Bradford