Get Roger Staubach talking about the Super Bowl, and he’s bound to bring up Vietnam’s Danang Harbor. He was stationed on a patrol boat there, as a young U.S. Navy officer, when he heard a radio broadcast of the first Super Bowl game between the Kansas City Chiefs and the Green Bay Packers in 1967. He had no idea that just five years later he’d lead the Dallas Cowboys to victory in Super Bowl VI, earning most valuable player honors. Harder still to envision was appearing in three more NFL championship games during his pro football career.

Forgive the understatement: the man has been in some high-pressure situations. He understands the anxiety and tension that comes with competing at the highest levels. He’s adept at making split-second decisions while opponents of unimaginable size and ability bear down on him. Even so, nothing else had been quite like the nervousness he felt while waiting on “pins and needles” in a meeting room at the Loews Vanderbilt Hotel in Nashville on May 22, 2007, Staubach says. It was an uncomfortable feeling for the ex-quarterback—not like firing quick passes from the pocket—because this time he didn’t have control of the ball.

Representatives of the 32 teams of the National Football League were deliberating in a nearby conference room. It was entirely up to them to determine whether hundreds of thousands of visitors would descend upon North Texas in February 2011 for the region’s first Super Bowl game. Their decision brought the potential of hundreds of millions of dollars in economic impact, and the certainty that the eyes of the nation would come to be squarely focused on Dallas-Fort Worth. Staubach and the other members of the North Texas Super Bowl Bid Committee crowding the meeting room had worked countless hours over the last six months to reach this moment. Refinements to their final presentation had been made late into the night before. All they could do now was wait. It was excruciating, and most of them silently began to question every decision they’d made up to that point.

“I guess it’s human nature when you’re sitting there, and the clock is ticking so loudly, that you start to second-guess, ‘Should we?’ ‘Could we?’” says Rosie Moncrief, wife of Fort Worth Mayor Mike Moncrief and a member of the bid effort.

Any minute, they were expecting, the commissioner of the NFL would walk through the door and deliver the league’s verdict. Would he enter the room to offer congratulations—or condolences?

Without possession of the ball to provide him a sense of control over the situation, Staubach improvised. He told jokes to keep the others loose. He juggled cream cheese containers for their entertainment—anything to make an agonizing wait more bearable.

Fielding a Team

Just meeting the NFL’s bare-minimum requirements to make a formal bid to host the Super Bowl is an arduous task. Hundreds of civic and business leaders from across the region must be mobilized. To do that, a group must be assembled to drive and orchestrate all that must be done. The first formal step for North Texas was recruiting George Bayoud, a Dallas real estate developer who consulted with the Dallas Cowboys on the construction of their new stadium, as president of the bid committee in the summer of 2006. But the Cowboys had been planning for this opportunity even before Arlington voters approved the funding that paved the way for construction of the $1.2 billion stadium—long before.

For the Arlington residents that had plunked down $325 million to help build the ball field, securing a Super Bowl was important in helping to recoup their investment.

“We knew that the only way that we’d make money, and the only way the Cowboys would make money, is to have the door unlocked and things going on,” says Arlington Mayor Robert Cluck, who championed bringing the Cowboys to town from Irving. “Once we got the land acquired and construction handled, that’s when things started coming down hard and fast as far as what we wanted to attract. And the Super Bowl was one of the top priorities.”

The first priority for Bayoud and the Jones family was finding an official leader for the bid, and they quickly thought of asking Staubach to become chairman. He wasn’t immediately sold on the idea, though.

“I was really caught up with everything I was doing, and I wasn’t sure I had time for it or what it meant,” he says. Eventually, however, “because it was sports, and it was Dallas, and it was football, I said, ‘Hey, I’ll take this responsibility on.’”

With those pieces in place—along with legal advisers from the Winstead law firm and a consultant named Robert Dale Morgan, who had worked on Houston’s successful 2004 Super Bowl bid—they next focused on bringing together a collection of talent to tackle the requirements laid out by the NFL’s official “request for proposals” on Super XLV, which was issued in the fall of 2006.

They wanted leaders from a number of different communities with varying areas of expertise. This group included former Dallas Mayor Ron Kirk, Mike Eastland and Michael Morris of the North Central Texas Council of Governments, Dan Petty of the North Texas Commission, and local business leaders Robert Estrada, Wendy Lopez, and Norma Roby. Anderson represented the Cowboys, Rosie Moncrief served for Fort Worth, and Arlington’s Mayor Cluck lent his help. The Dallas Convention & Visitors Bureau loaned out its expert in sports tourism, Tara Green, as executive director for the project.

The game would be played in Arlington, but no one city in North Texas—no one city anywhere—is capable of hosting a Super Bowl by itself. The reason: the event has simply become too big. The 200,000 or so people expected to descend upon a region create demand for tens of thousands of hotel rooms, hundreds of buses and limousines, and thousands of taxis and rental cars. Not to mention the strain on restaurants, bars, and other area attractions.

As a result it was decided early on that the bid would have to be a regional affair, so major regional organizations were brought into the fold: Petty’s North Texas Commission and Eastland and Morris’ North Central Texas Council of Governments.

By using their contacts with city governments, county governments, chambers of commerce, and convention and visitors bureaus, the bid committee created a network that helped secure the contracts and anti-price-gouging pledges from hotels, taxi companies, rental car agencies, and event venues that were necessary to meet the NFL’s requirements.

Dan Petty, president and CEO of the nonprofit North Texas Commission, says bringing Super Bowl XLV to Arlington required more regional cooperation than any effort since the building of Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport (the project that precipitated the creation of the North Texas Commission itself) in the late 1960s and early ’70s.

By all accounts, responding to the NFL’s Super Bowl RFP—a 244-page document—was a monumental logistical challenge. However, it was far easier than it might have been, thanks to an earlier failure.

The Playbook

Dallas was eliminated as a possible site for the 2012 Summer Olympics by U.S. Olympic bid evaluators in 2001. While that effort fell short, it left behind a web of relationships that had been established between community leaders, CVBs, and those in the hospitality industry. So when it came time to think about the Super Bowl, the bid committee was able to start with a blueprint rather than a blank slate.

“Were it not for the Olympic bid, I don’t know that we would have done so well so quickly on the Super Bowl bid,” says Green, who was part of both efforts.Just meeting the NFL’s bare-minimum requirements to make a formal bid to host the Super Bowl is an arduous task.

Morris, the NCTCOG transportation director, turned to the outline he’d already devised for “Dallas 2012” when it came time to develop a new transportation plan. But more than that, he says, the Olympic experience made him realize the importance of securing support from local governments early in the process.

“If you remember back to the Olympics, we didn’t have the Dallas City Council through the whole process, and at the very end the city council never supported it,” Morris says. “I said if I’m involved [with the Super Bowl bid], I’ll help get the support, but we’re going to get it early. And we did get it early, and everyone was on board, and it is a North Texas thing.”

The Super Bowl XLV RFP contained 13 chapters featuring specifications on everything related to ensuring that hundreds of thousands of visitors can be housed, fed, transported, and entertained in North Texas during the first weekend of February next year. The NFL’s Special Events staff pores over details about the stadium, game tickets, security, accommodations, a media center, transportation plan, venues for satellite events, relations with local governments, and plans for charitable components like the construction of a youth education center sponsored by the league. Bidders must answer a series of questions to indicate that they can comply with the requirements, and describe any measures they’ve taken to go above and beyond the minimum effort.

Denis Braham, the Houston-based CEO of the Winstead law firm, led the team of legal advisors to the bid committee. He had already worked with Morgan on Houston’s successful bid for the 2004 Super Bowl (as well as a failure by Houston to secure the 2009 game). He says an important part of making a bid is realizing that the NFL is looking to bring more than just a game to a region; the league wants to see evidence that a lasting impact will be made on the community.

“The bid is a very intricate package, and one could think quite easily that just building the stadium the Jones family has built was what did it, and it clearly was a very key factor, but it’s not just about the stadium,” Braham says. “The NFL themselves aren’t just interested in coming to a city, putting on the event, and leaving. They also are interested in having the positive impact that bringing a Super Bowl to a city will make for that city or that area.”

Once all the necessary contracts had been secured, a transportation plan designed, the anti-gouging pledges signed by hotels and rental car agencies, a host committee budget designed, and all the other minutiae involved had been determined, Winstead’s lawyers examined it all carefully. The necessary documents then were assembled into eight binders’ worth of material that, when stacked, reached more than 3 feet in height. One of the binders—a mere 2 ½ inches thick—was an executive summary (“the pretty version,” Green calls it) that was sent to each of the 32 NFL team owners in April of 2007.

In the end it was that small group of high-powered egos, each with their own interests, that would determine whether North Texas would come out a winner.

“It’s kind of like a trial lawyer going in front of a jury,” Braham says. “You can’t quite tell what the result is going to be, even if you’ve got a really good case.”

Drive to the End Zone

The final hearing for North Texas Super Bowl hopes came on that day in May 2007 in Nashville. The competitor cities were Glendale, Ariz., and Indianapolis.

The Arizona Cardinals’ home had already been awarded the 2008 game, so no one on the host committee was concerned about losing out to it. With both the Cowboys and the Indianapolis Colts boasting new stadiums and making bids for their first Super Bowls, it was expected that the contest would boil down to a two-horse race.

Indianapolis promised to be a formidable opponent. Its Lucas Oil Stadium would open a year before the Cowboys’ new home, so some owners might figure that the Colts should be in line ahead of North Texas. Indianapolis also had already secured the financing for its host committee, whereas North Texas was merely pledging to raise the $30 million for its bid. And there were the NFL’s internal political considerations: a divide between high-revenue clubs (like the Cowboys) and lower-revenue clubs (like the Colts), with sentiment that could swing the vote in the smaller market’s favor.

Regardless, the North Texas bid committee was confident. They believed that the not-yet-built Cowboys Stadium would be a jewel, with tens of thousands more seats than Indianapolis was offering. More seats meant more revenue for the NFL. Dallas-Fort Worth, the fourth-most-populous metropolitan region in the United States, also had a decided advantage in available hotel rooms and venues and all manner of other amenities compared to Indianapolis, the country’s 29th largest metro area.

Still, it would come down to the votes of the 32 owners sitting in a conference room at the Loews Vanderbilt Hotel. The North Texas team knew of only one vote they could count on—that of Jerry Jones. Because the decision was made via secret ballot, even verbal promises of support from other groups weren’t entirely reliable.

That morning the Jones family and five representatives of the bid committee—Staubach, Petty, Rosie Moncrief, Bayoud, and Anderson—filed into the owners’ meeting to make the final pitch. Petty remembers being “star-struck” in seeing the NFL owners waiting to hear from them. “You get the feeling this is competition at its highest,” Petty says.

Staubach had arrived late the night before and met with his fellow committee members early that morning to go over their strategy. They were opting not to give a traditional CVB-style speech accenting the tremendous venues and other attractions in the region.

“ ‘We’re not trying to convince you we have good hotels. We know we do. What we’re trying to convince you is this region lives for this game. These kids grow up loving football,’ ” Anderson says of the team’s final approach.

With 15 minutes to address the ownership, North Texas began with a video narrated by legendary sports broadcaster Pat Summerall, who pronounces at the start, “There is a place, where football is more than a sport. … For the people here, football is who we are. It’s in our blood.” That was followed by scenes of peewee football, high school football, college, on up to the pros. The heritage of Texans in the NFL was highlighted, as was the history of “two Texans”—Lamar Hunt and Tex Schramm—who were instrumental in the AFL-NFL merger and the birth of the Super Bowl itself. Then came a three-dimensional, computer-generated tour of “the new Texas Stadium,” which was “designed to be host to the grandest spectacle in sports.”

Next Staubach took his turn. He doesn’t like to stick to scripts, so he spoke from his personal experience with the Super Bowl, and about all that it had meant to his life. He remembered Danang Harbor. He recognized his own good fortune in being able to later join the Cowboys and play in four NFL championship games.

“I mentioned that I was 2-2 in Super Bowls, and I wanted to be 3-2 and win this one. And I said ‘Mr. Rooney [owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers, the team to whom Staubach suffered those two losses], you owe me,’” Staubach recalls. (Afterwards, Rooney gave him “a wink and a hug,” so Staubach thought he’d won at least one vote for North Texas. But Jerry Jones dispelled that idea: “He voted for the small-market team, Indianapolis. I promise you, Roger, he didn’t vote for us.”)

In finishing, Staubach stressed how much hosting the game would mean to North Texas and pledged that the region would deliver the biggest and best event possible. Rosie Moncrief says the response to Staubach’s speech was “uplifting.”

“The applause for Roger was so long and so loud, it gave me goosebumps,” she says. “This is a room filled with pretty healthy egos. This is a room filled with owners that might have a little Cowboys envy—because you have low-revenue clubs and high-revenue clubs and the Dallas Cowboys have always been at the top. I would just venture to guess that there is a little bit of jealousy. But Roger has been the consummate professional throughout his career, as an athlete and as a businessman.”

Soon the bid committee representatives left to rejoin the rest of the North Texas contingent in one of the hotel’s meeting rooms. Only the Jones family was allowed to remain to hear the other cities’ presentations and to watch the vote. Anderson says the pitches from Arizona and Indianapolis “had tons of bells and whistles.”

“Their videos were powerful. They brought in all the superstars. It did make you nervous, sitting there, going, ‘OK, now what are they going to decide?’” she says.

Each of the team owners whose regions were bidding was given five minutes to sell his colleagues. Jerry Jones stood and told his fellow owners “We won’t let you down.” Anderson describes her father’s speech as an “emotional, powerful plea.”

But, again, no one knew precisely how those 32 clubs would cast their ballots.

“There was definitely a political effort to go in and do low-revenue club vs. high-revenue club,” Anderson says. “You know, politics exists in everything. So, from that front, you never really know what people are going to do. I think at the end of the day, there were enough who said, ‘You know what, we’re going to put politics aside and go with what’s best for this league.’ And that’s how they vote.”

The Thrill of Victory

In the meeting room where the members of the bid committee waited, Winstead’s Braham knew that one of two things was about to happen. He’d been through this process twice before with Houston. If the commissioner entered and offered his hand in congratulations, the group would be escorted down the back stairs of the hotel, to the conference room where the owners had met. Quickly they’d be ushered out to a press conference where the NFL would officially announce North Texas as the home of Super Bowl XLV.

“There’s no better feeling than being escorted down the back stairs knowing you’ve won, and there’s no worse feeling than not,” Braham says. “At that point, you’ve put your blood, sweat, and tears, and the effort of an entire community, into it. Everything’s riding on that last vote.”

The NFL’s procedure for determining a Super Bowl host city calls for up to four rounds of secret ballots. In the first three rounds, a city has to garner support from three-quarters of the ownership to win the bid. If no city does that in any of the first three rounds, then a fourth round is held—with only the top two vote-getters in contention. In that fourth round, a simple majority carries the day.

It was clear early on that Arizona would be out of the running, but no team had enough support through the first three rounds. Indianapolis and North Texas remained to fight it out on the fourth ballot. As each vote was counted, a slip of paper was deposited into one of two piles as the owners looked on.

“We’re trying to figure out: is our pile on the right or is our pile on the left? It was probably one of the most nerve-racking experiences I’ve ever sat through,” Anderson says. “I mean, you’ve worked so hard, and so many people back home are so anxious, and you don’t have any control. You’ve done all you can do.”

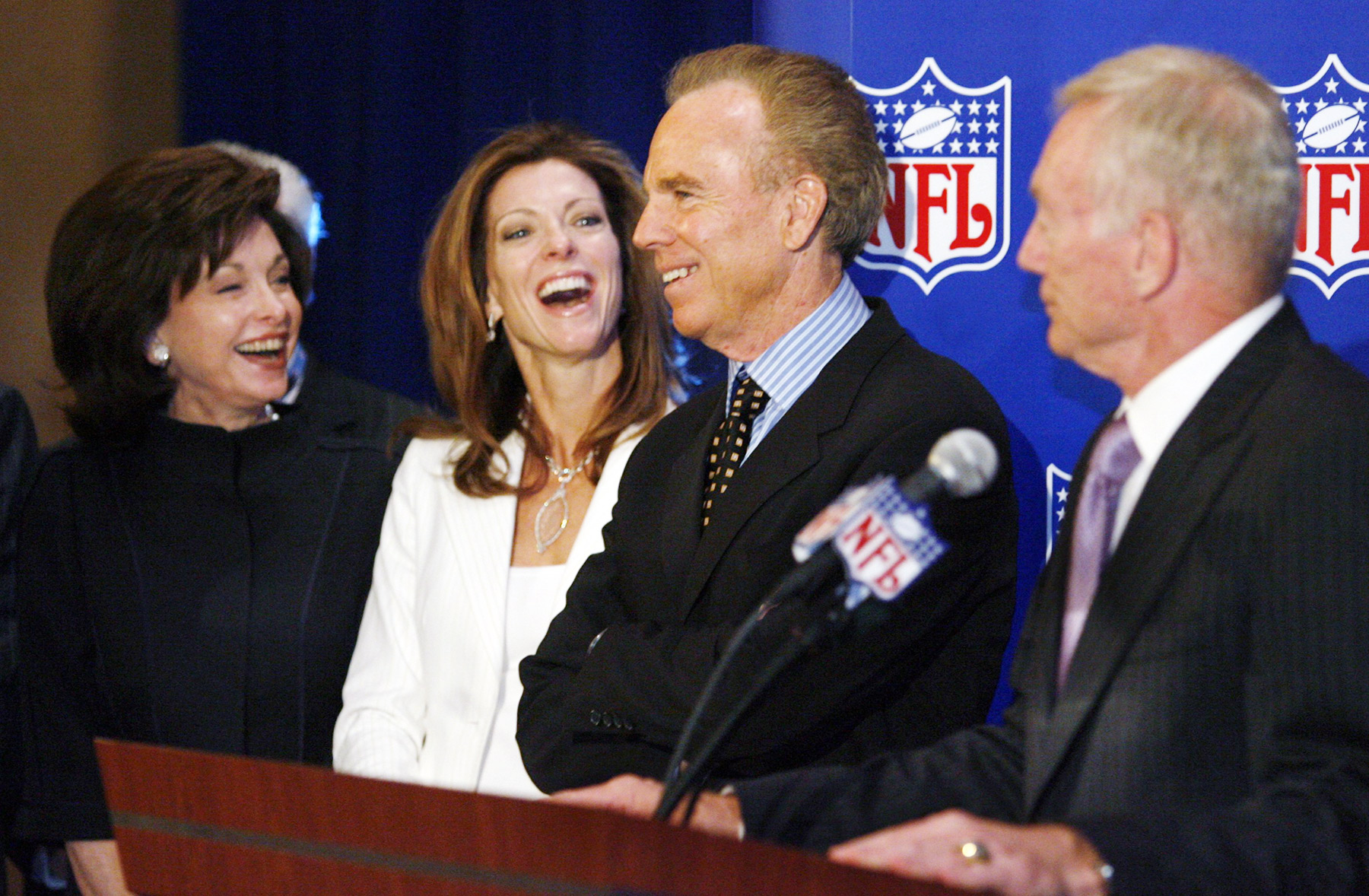

At long last, with each vote in one of the piles, Commissioner Roger Goodell strode to the podium to announce the result: “Super Bowl XLV will be hosted by”—Anderson remembers a seemingly interminable pause here—“North Texas.” At that, the entire Jones family—Jerry, Gene, Charlotte, Stephen, and Jerry Jr.—burst into tears.

“It was just jubilation. It was excitement. It was relief. It was oh-my-gosh. We just ran out of the room to go find Roger and the committee,” Anderson says.

Since it is a secret ballot, the NFL doesn’t reveal the vote totals. By all accounts, the final tally was close. Some of the people involved contend that it came down to one vote, with North Texas taking the day, 17 to 15. The consensus among those involved in the bid is that it was the new Cowboys Stadium itself that tipped the balance.

“At the end of the day, our stadium holds more people, more corporate suites. You know, we were just more,” Anderson says. “We could expand the capacity of the game, and that was pretty much the bottom line.”

Whatever the reasons, the owners had picked North Texas. Goodell entered the North Texas waiting room, shook Staubach’s hand, and said, “Congratulations.” The room vented hours of built-up tension and erupted in an explosion of joy with high-fives and hugs all around.

“For the whole region, it’s a real success. Personally, I would have liked to have had a victory over the Steelers. I’d trade another victory over the Steelers for it,” Staubach says of how it felt to win the bid. “It’s a different feeling, but it’s really going to be a great thing for the region.”

Time to Shine

Members of the North Texas Bid Committee filed into the press conference, with Goodell, Jerry Jones, and Staubach leading the way. The others crowded alongside the podium as the commissioner made the official announcement to the assembled members of the media and quickly turned the podium over to Jones.

The Cowboys owner recognized the bid committee’s efforts and thanked the mayors of Fort Worth and Arlington for their help. (Dallas was in the midst of a mayoral election runoff, so Jones merely mentioned the city’s leadership in general.) He called hosting the Super Bowl “a privilege and an honor.”

Staubach took the podium briefly, to call winning the bid “the thrill of a lifetime” while comparing the wait on the results of the owners’ vote to the anxiety that had come while awaiting the birth of his grandchild just the week before. Then Jones returned to the microphone to answer questions from the press.

At one point the Dallas Cowboys owner had to fight off tears, pausing a second to collect himself, as he explained just what this day meant to him. “I don’t mind telling you, it was an emotional time to hear that we were going to play the Super Bowl in Dallas’ new stadium,” he said.

Off to his right, among the closely packed members of the bid committee, Green found herself unexpectedly facing the reality of the work that lay ahead to pull off an event of such magnitude. Though it would be nearly another year and a half before she and others would begin working full-time on the effort, she was unable to put off thinking about what was to come.

That’s because her BlackBerry was going crazy. “I’m thinking, ‘Are you kidding me?’ They’d just found out that we’re hosting. The first message I get, it’s from someone I don’t even know, wanting a job,” Green says. “I thought, ‘I don’t even have a job on the host committee. Are you serious?’” That first note was followed by an offer to volunteer for the effort, then someone asking how he could buy a ticket for the game that was still more than three years away.

The eyes, and expectations, of North Texas were already upon them. It was time to get to work.

DALLAS VS. INDY

Cowboys Stadium

Opened: 2009

Price Tag: $1.2 billion

Size: 3 million square feet

Capacity: About 100,000 (including standing-room in end-zone plazas)

Luxury Suites: 315

Fun Fact: Consists of 14,100 tons of structural steel (equal to the weight of 92 Boeing 777s).

Lucas Oil Stadium

Opened: 2008

Price Tag: $720 million

Size: 1.8 million square feet

Capacity: 63,000 for football

Luxury Suites: 137

Fun Fact: In 2010, it will be linked to a newly expanded convention center and several hotels by a pedestrian connector.

Listen to Jason Heid’s interview with Roger Staubach.