This image comes courtesy a perambulating FrontBurnervian who found a mind-boggling scene in Uptown, which is supposedly the city’s most walkable neighborhood. Let’s walk through this one. The full-flavor image is below.

FrontBurner

Among the Dallas City Council, it will be difficult to even discuss adding light density—duplexes, triplexes, and quadplexes—to neighborhoods that presently allow only single-family homes. A Tuesday morning meeting about researching the matter was more pugilistic than instructive, as a majority of the Council’s housing committee sought to quash even the possibility of adjusting the mix of housing types in these neighborhoods.

Briefings aren’t usually so punchy. The purpose of this special meeting of the City Council’s Housing and Homelessness Committee was to talk, for staff to explain its process and gather questions from council members as City Hall rewrites its land use and development codes. These discussions are perhaps the most important happening today at 1500 Marilla. They will shape how our city grows (or doesn’t) by dictating what can be built and where.

Dallas neighborhoods are becoming more expensive. According to a recent analysis of the market, most residential construction creates houses that sell for a median of $1.4 million. After that, we build a bunch of houses that cost about $670,000. A different analysis found a gulf of 33,600 rental units for individuals who make 50 percent of the area’s median income, which, based on analysis of Census labor data, includes more than one third of the city’s residents.

In short, too many people already can’t afford to live here. What happens if you buy a $1.4 million house but can’t find a nearby dry cleaner because the owner of that business had to move to Celina? Furthermore, duplexes and triplexes contribute more per acre to a city’s tax base than a single-family home. This is a math problem. The city isn’t advocating for doing away with single-family; it wants to research the result of creating more of a mix of housing types, which, if successful over time, will contribute more to the city’s tax base than the status quo.

There are, of course, many reasons for these market trends. Some things the city has control over (permit processing, for instance) and others it does not (interest rates, supply-chain problems). City staff are tackling one of the things that could help impact the supply: allowing more than one unit of housing on lots that presently can hold only one.

Staff on Tuesday presented to a largely hostile audience, one that had little patience for suggestions that could change the makeup of most of the city’s zoning. The takeaway among six of the nine members who attended the meeting: stay away from our single-family residential neighborhoods. “I want the families in the single-family districts to know we have their best interests at heart,” said Deputy Mayor Pro Tem Carolyn King Arnold, whose District 4 includes south and east Oak Cliff.

We’re almost to the 50th installment of this series, and our 49th entry comes from the Cedars neighborhood just south of downtown.

A resident who uses a wheelchair told us that the city finally updated the Cedars sidewalks on South Akard from Griffin to Corinth streets. Those updates included Americans With Disabilities Act-compliant curb ramps that allow wheelchairs, walkers, and strollers access to a sidewalk or crosswalk.

“Granted … they installed the handi-lip at the south corner of Beaumont and Akard at such a sharp angle that it’s largely impassable in a wheelchair because the footplate gets stuck, but, seriously, such an improvement!” Melody Townsel said.

Courtesy Melody Townsel

But there’s a problem. The same ramp Townsel mentioned was recently “asphalted into oblivion,” and construction blocks the sidewalk.

Five members of the Dallas City Council want the city to research changing its development code to make it possible to build more housing units on lots that presently allow only single-family homes.

Councilman Chad West, of North Oak Cliff, sent a memo to the mayor on Wednesday that directs city staff to investigate changing the code to allow for duplexes, triplexes, and quadplexes in residential neighborhoods. The memo also takes aim at lot sizes. Most of Dallas’ residential lots are between 5,000 square feet and 7,500 square feet. West would like to see the city’s minimum reduced to 1,500, which he believes would encourage manageable density on the city’s precious existing land. The memo asks for a Council briefing in the next 30 days.

“Housing in the city of Dallas is becoming unaffordable for many would-be residents due to a lack of available housing units,” the memo reads. “Reducing minimum lot sizes and increasing the number of residential dwelling units on a lot will allow for the development of additional dwelling units in residentially zoned areas.”

West was joined by colleagues Jaime Resendez, who represents southeast Dallas; Jaynie Schultz, the councilwoman for North Dallas; Paula Blackmon, of White Rock Lake; and Adam Bazaldua, who is over South Dallas and Fair Park.

West says he’d like to see the city follow Houston’s lead, which in 1998 dropped its minimum lot size from 5,000 square feet to 1,400. It’s not uncommon to find blocks of townhomes and duplexes scattered among single-family residences there.

In July, he laid out his plan in a Dallas Morning News opinion piece. This week’s memo is an important procedural step so that staff can eventually present its findings to the City Plan Commission for consideration. The City Council will ultimately have to approve any changes.

Dallas is trailing other major Texas cities in addressing its residential zoning amid a housing crunch. Austin dropped its minimum lot size to 2,500 square feet this summer, powered by recent research that has found that allowing more infill development can lower housing costs by creating more places for people to live.

Moves to Tweak Scooter Rules Fall Flat With Council Transportation Committee

The best laid plans of mice and men often go awry, the proverb goes, and that is especially true when it comes to the city managing electric scooters.

In the spring, the Dallas City Council approved a second attempt to introduce scooters to the city, establishing limits on how many scooters would be deployed, where they could operate, and how they would be distributed around the city. On Monday, a Dallas City Council committee got a report on how the new attempt at micromobility was faring. It needs work.

This little corner of the website has been quiet for some time—email me if you encounter infrastructure or construction or anything else that makes it a pain to walk—but that doesn’t mean the problems are fixed.

The photo above is at Ervay and Federal streets in the downtown of the ninth largest city in America. Energy Plaza is ripping up its sprawling terrace and has taken in a lane of traffic to dump its trash. The sidewalk is gone, and you’re forced to cross to the east side of the street.

Or you can see if you can navigate your way out and deal with oncoming traffic. This is admittedly a bit of user error here; I should’ve paid closer attention and crossed instead of stubbornly try to navigate the length of the construction, I admit. But it’s a miserable experience if you’re on two feet and trying to hurry to get out of this heat.

Welcome back to Dallas Hates Pedestrians. We’ll get to 50 soon.

A real estate consultant named Paul Carden was invited to Fair Park in late April to share an idea that is anathema to most Texans: vehicle congestion can sometimes be good.

He spoke on a stage in the Centennial Building during the EarthX conference over Earth Day weekend, not the setting one would expect for advocacy of idling vehicles. But congestion, he said, is why some neighborhoods can attract businesses and others cannot.

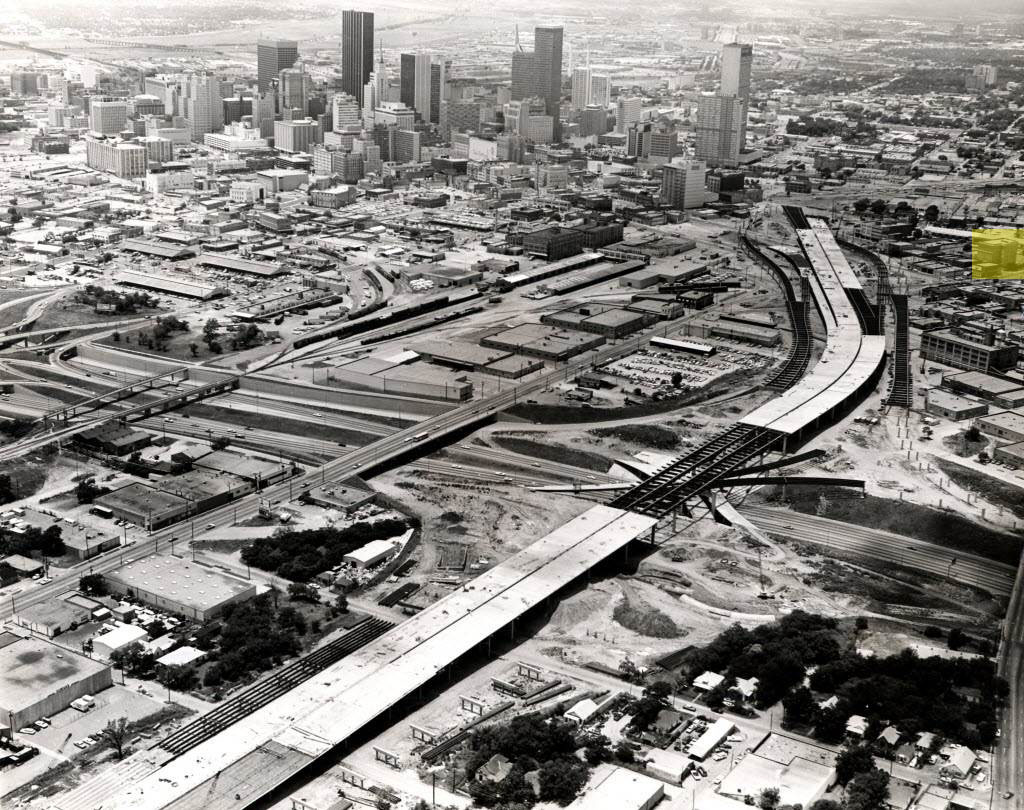

Carden, a vice president at real estate firm Venture Commercial, wore jeans and a blazer and spoke with the enthusiasm of a teacher who has been begging the administration for years to teach this elective. His stage partner for the afternoon was Caleb Roberts, an urban planner at a company called Gap Strategies who delivered a complementary sermon with a quick smile after each point. Roberts cued slides that showed how highways eliminate some destinations before they create others decades and miles away, by shifting congestion—and investment—to new parts of town, leaving older parts behind. On screen popped photos of the vibrant, dense 1950s-era neighborhoods just south of downtown Dallas that were later gouged by interstates 35 and 45. Then he summoned pictures of North Dallas from the same period, showing empty fields and then the businesses that filled them.

Roberts is not from Dallas, and the two had never worked together. But a mutual friend tapped them for the EarthX presentation because their messages fit: highways serve cars, not necessarily neighborhoods and the people who live in them.

Oak Cliff’s Five Mile Creek Trail Project Gets $6.5 Million Boost from Federal Grant

The federal government has awarded the city of Dallas a $6.5 million grant to finish designing and engineering the remainder of the Five Mile Creek trail from U.S. 67 into the Trinity Forest through southern Oak Cliff.

The money comes from President Joe Biden’s discretionary RAISE (Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity) grant program, a $2.2 billion pool for which state and local governments can apply to pay down infrastructure projects that reconnect communities.

The money will be paid to the city of Dallas, which will then work with the nonprofit Trust for Public Land as a partner. The Trust is leading the project, which will include three new parks and 17 miles of trail that extend east from near the Westmoreland DART station into the Trinity Forest. It will link up with the under-construction 50-mile Loop Trail near the existing AT&T Trail and connect to points north.

This is the only grant awarded to the city of Dallas during the 2023 disbursements; the federal government awarded $2.2 billion in grants but received about $15 billion in applications.

“This is another shot in the arm for the project,” says Robert Kent, the Trust’s Texas director. “This is the momentum we need to move this thing to the finish line.”

The Dallas City Council today gave the state of Texas permission to pursue funding to remove and trench I-345, the currently elevated 1.4-mile highway separating downtown and Deep Ellum. The Council’s vote was delivered with the energy of a sigh despite weeks of parliamentary backroom wrangling among some council members who wanted more time to study the plan before approving it.

It was a near impossibility to convince the Texas Department of Transportation to do anything that altered the amount of traffic lanes that slice through Dallas’ urban core. TxDOT owns the 50-year-old highway, not the city of Dallas. It is among the shortest on the national highway network, a stub that connects to Central Expressway, Woodall Rodgers, and interstates 30 and 45. It is, more than anything, a concrete connective tissue that allows freeway traffic to flow in all directions, a traffic engineer’s dream. TxDOT cites traffic counts of 180,000 cars on the roadway per day. Powerful transportation officials don’t seem capable of imagining a world in which the highway doesn’t exist.

Partly that is because they understand the game. Vehicle capacity on highways is the top transportation priority of Gov. Greg Abbott, whose edicts dictate which projects are funded and which are not.

There have been grassroots calls for nearly a dozen years to remove I-345 and replace it with a boulevard and a reconfigured system of surface streets that would absorb the traffic. But because of its status—a state-owned thoroughfare on the National Highway Freight Network—the city had no power to pursue something so radical. The most the City Council could do was stall by voting against the resolution, a move that had little support among the 14 council members who were present for Wednesday’s vote. (Mayor Eric Johnson was absent because he was speaking on a panel about sports in Qatar.)

The City Council voted unanimously to support TxDOT’s preference for the highway, which it calls the “hybrid plan,” with some caveats.

“This is not a perfect solution, in my opinion, but at the end of the day, what we can say if we support this is that today, TxDOT and the city of Dallas have decided to take down a highway and are going to put something better there in its place,” said Councilman Chad West, the loudest and loneliest pro-boulevard voice on the City Council.

Dallas’ nearly three-year ban of electric rental scooters will lift Wednesday, letting loose a comparative trickle of two-wheelers on city streets. (The city hopes the optimal word there is “streets.”)

Since banning the mode of micro-mobility under the guise of “public safety” in September 2020, Dallas city staffers have worked to figure out why and how these devices became such a nuisance. City Hall believes it has established a series of new regulations that will prevent a free-for-all, starting with how many scooters you’ll see and where you will see them.

Just three operators will have permission to drop their rides. Bird and Lime are back, along with the Denver-based newcomer Superpedestrian. Each company will be allowed to bring 500 scooters at first, and the city will evaluate performance every three months. They could be allowed another 250 each time, with a cap at 1,250. That means no more than a total of 3,750 rental scooters in Dallas; that’s likely a fraction of how many were here during peak Scootermania.

Not that Dallas could track them. During the first draft, the city had no real structure for scooter registration, meaning new companies were allowed to enter the market and weren’t limited to a total they could drop. Dallas couldn’t even get the operators to adhere to a curfew. Too, some were unwilling to share ridership data that the city wanted to help inform policy.

“Everything was learning. We went from this not even being a technology to being bombarded with it,” says Kathryn Rush, chief planner with the Department of Transportation at the city of Dallas. “It was a totally new regulatory environment that really isn’t very comparable.”

Transportation Officials Make Public Plea to Support I-345 Trenching Plan

Michael Morris, the most powerful transportation official in North Texas, is ready to be done with I-345.

The Texas Department of Transportation would prefer to trench the highway 65 feet below ground, on the east side of downtown, which would allow traffic to flow and development to come on decks over the roadway and on surplus right of way. But some on the Dallas City Council still have questions about how this would affect the city generations from now.

Morris, the transportation director of the North Central Texas Council of Governments, believes that this is a simple decision. There is money in Washington and in Austin, and that money can be spent tearing the freeway down, digging a 65-foot-deep trench, laying as many as 10 lanes in that depression, and reconnecting existing streets over the below-ground freeway.

Later, Morris says, the city and his organization can figure out all the economic development potential surrounding this project, including how to pay for decks over the freeway that could hold some manner of buildings or parks. The COG, as his organization is known, helps secure state and federal dollars for major infrastructure projects like this one.

And this one is indeed major. TxDOT’s trenching plan—the so-called “hybrid” plan—will cost at least $1 billion and will require years of construction. The state won’t pay for decking, and the city will have to purchase surplus right of way freed up when ramps are torn out.

“Make hay while the sun shines,” Morris said last Monday night, May 8, during a specially called panel of top city staffers, prominent developers, and representatives for downtown and Deep Ellum. It was the unofficial kickoff to a month of policy decisions that will end with the City Council either giving its support for the state’s trenching plan or continuing to study other possible plans for I-345.

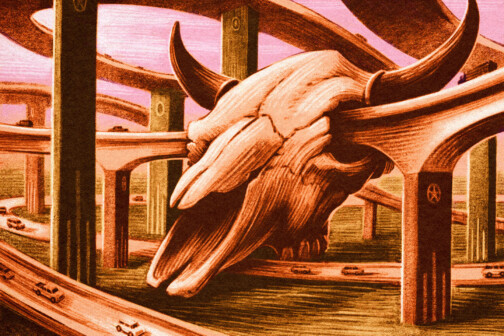

In 1982, the Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture published a 95-page book titled Imagining Dallas, which contained eight essays about our city written by notable Dallasites, including Wick Allison, the co-founder of D Magazine. In his contribution, reprinted below, the great Bill Porterfield wrote about the city’s unemotional march into the future.

In conjunction with a series of talks about the city on May 25, the Dallas Institute is revisiting Imagining Dallas. Porterfield’s piece was originally titled “Man and Beast in the City: Twain or Twin.” At the time of publication, in 1982, Porterfield was a columnist for the now-defunct Dallas Times Herald and a creative writing teacher at SMU. When he died at the age of 81, in 2014, his son Winton told the Austin American-Statesman: “He was a force of nature really, kind of a walking thunderstorm. He was very creative, he was passionate, he was tempestuous, he was profane, he loved ideas, and he loved words and books. Obviously, he loved women; he was married six times. He loved whiskey and dogs and cheeseburgers. He was a really good dancer and he didn’t wear underwear. He was a short man but a man in full.”

Below, we present his thoughts on the city, from 1982.