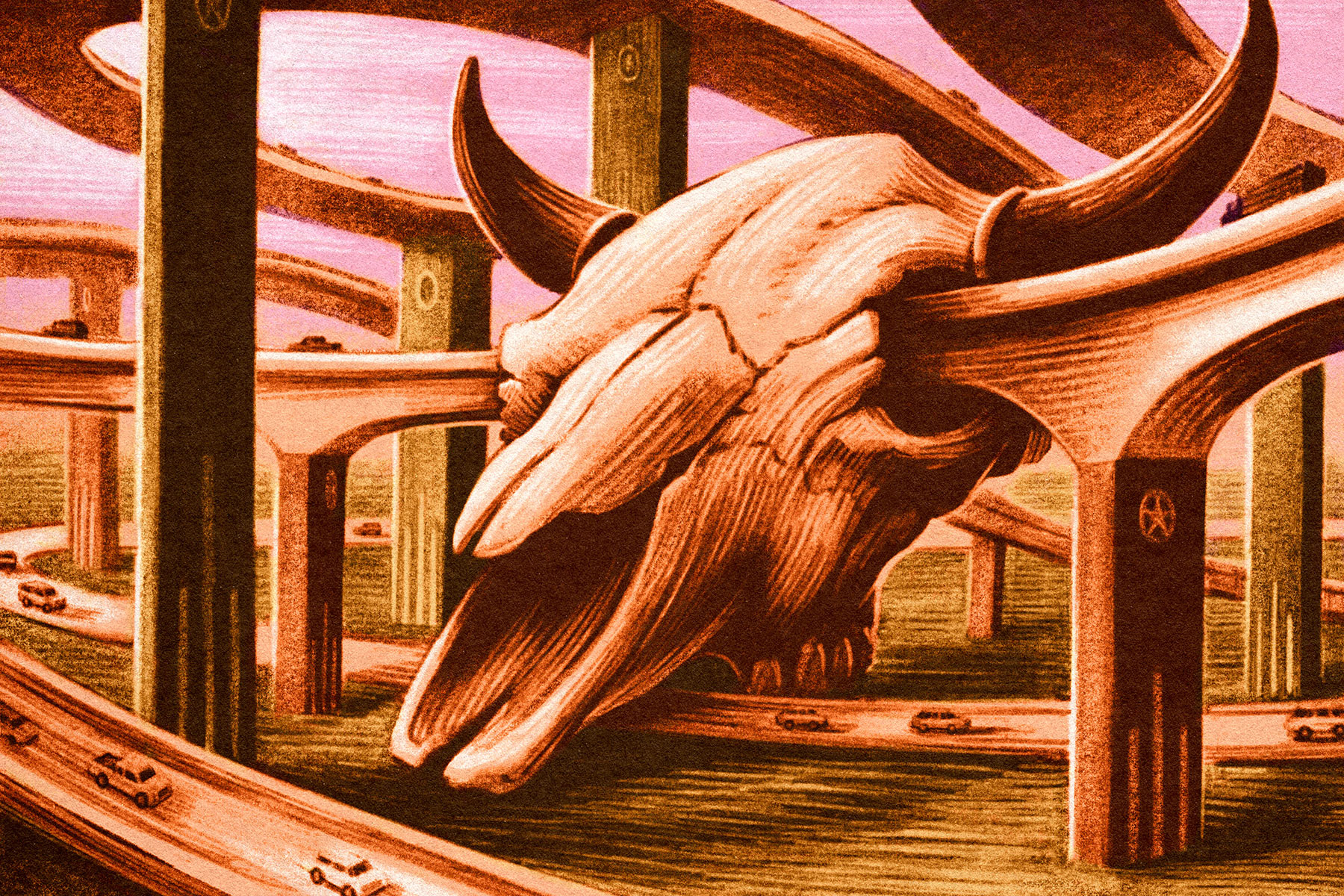

In 1982, the Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture published a 95-page book titled Imagining Dallas, which contained eight essays about our city written by notable Dallasites, including Wick Allison, the co-founder of D Magazine. In his contribution, reprinted below, the great Bill Porterfield wrote about the city’s unemotional march into the future.

In conjunction with a series of talks about the city on May 25, the Dallas Institute is revisiting Imagining Dallas. Porterfield’s piece was originally titled “Man and Beast in the City: Twain or Twin.” At the time of publication, in 1982, Porterfield was a columnist for the now-defunct Dallas Times Herald and a creative writing teacher at SMU. When he died at the age of 81, in 2014, his son Winton told the Austin American-Statesman: “He was a force of nature really, kind of a walking thunderstorm. He was very creative, he was passionate, he was tempestuous, he was profane, he loved ideas, and he loved words and books. Obviously, he loved women; he was married six times. He loved whiskey and dogs and cheeseburgers. He was a really good dancer and he didn’t wear underwear. He was a short man but a man in full.”

Below, we present his thoughts on the city, from 1982.

Those who come after us seeking to find out something about the way we live and what made us laugh and what made us cry may have to be satisfied to root around in artifacts dealing with company transfers, mortgage payments, and notes to all kinds of people asking them how to please discontinue service. It is difficult to say how this will all work out.

The fact is that as time races on, fewer of us can say: this is the place where I was born and where generations of my family were born. My father and his father before him lie out in the cemetery. There I will lie when my time comes. My children are here and my grandchildren and their grandchildren will be. This land, this house, this village are part of me, and I am part of them; we can neither be separated nor exist one from the other.

We are a mobile people now, our families split like the atoms, and most of us leave the place of our growing up for good. Oh, we may return once every year or so to see the folks, but after they are dead and buried, there is usually no reason for us to go back where we came from.

We do not preserve our dead for the same reasons as the Egyptians. We pickle the dead because morticians have gotten to our legislators to make of it a requirement, so that undertakers may preserve and perpetuate themselves. We bury our dead and leave them, wondrously and expensively intact, rarely returning to remember.

Recently I was in the Hyatt Hotel in Fort Worth and remembered that before they disemboweled and renovated it, it was the old Texas Hotel where President Kennedy had spent his last night before coming to Dallas. I thought that surely they would have spared the room where Jack and Jacqueline spent their last night together on this earth. I could see it suspended up there somewhere behind the soaring atrium, a time capsule with its quaint old furniture and sad bed, a room quite unlike any of the others in the hotel, for nothing in it had been disturbed since November 22, 1963. I thought, “Surely the wrecking ball was checked and did not swing into the Kennedy suite.” But I knew the answer even as I prayed that it would not be so. As the bellhop put it, “We commemorated it with a historical plaque, but it was remodeled like the other rooms.” A flashback: the maids probably had the sheets changed and the toilet sanitized before the presidential party crossed the Trinity. We grow away. We come to dress and speak differently, to think thoughts other than those that sustained our fathers. We forget.

This, however, cannot be said to be true of all people. In New England and in the South, for example, we still have pockets of people who hang on dearly to the taproots of tradition.

But theirs is a futile battle, and the worldwide fact of it was brought home when I read of the tragedy that overtook an aristocratic family in the south of France when they refused to give up their home so that it could be sold for taxes and debts. The head of the family, a young nobleman named Jean-Louis de Portal, died of bullet wounds after trying to hold off paratrooping police from taking the château, which had been in the Portal family since the Middle Ages.

When police stormed the chateau, they had to disarm Jean-Louis’ mother and his sister. In one of the rooms of the 30-room house, they found the body of the Baron, who had died two years earlier, after a futile court fight to keep his family estate. His wife had sealed his body in a lead coffin; then she and her son and daughter took up hunting rifles, made of the house a bunker, and held off warrant servers and police for two years. The old woman and daughter were jailed, and someone else who bought the place at an auction has since moved in.

A man’s home is no longer his castle, especially if he muddies up his title with mortgages. If the authorities want it bad enough, for debt or taxes, they can take it here as well as in France. Most of us, moving about as we do, never live in a house long enough to pay off the mortgage, much less hang around enough to get attached to it in the passionate sense that gripped the Portals.

I have, in my 50 years on the American continent, lived in 30 houses. In the 14 years I’ve lived in Dallas, I have lived in 14 different places. I don’t want you to think ill of me, but I’ve also had a succession of wives, children, dogs, cats, and horses, all of which I’ve taken with me from one more or less green pasture to another. There are certain recurring themes that run through the family. “Here today; gone tomorrow”; “Lock, stock, and barrel”; “Hello and goodbye” are the words that run together. I will go to my grave hearing the plaintive cry of my children calling from the back seat of the car: “Daddy, can we stop up ahead and use the bathroom?” Surely, the Porterfields and the Joads are not the only nomads in America. On the contrary, I feel in my restlessness quite at home and in the mainstream. None of the houses or offices I have occupied are sacred to me. My dream place is, but I’ve yet to find it.

And yet I was moved by the Portals’ plight, felt myself identifying with them and hating the system that said after hundreds of years and the passing of even more generations it was not theirs after all but someone else’s, anyone else’s who could come up with the money owed the debtors and the government, anyone else’s who had a quick finger at an auction.

You don’t have to be of the nobility to understand why the Portals knew the chateau was theirs, regardless of how prodigal they had been, regardless of what the law said, regardless of who held liens and whatever kinds of official papers. You don’t have to be a Scarlett O’Hara clinging to Tara to see young Jean-Louis as heroic. You simply can be an old-timer in a shack who refuses to budge for a highway right-of-way. You might even be a Dallas homeowner who refuses to pay the inflated city tax on your place. If nothing else, the Portals had squatter’s rights.

I know a ranch family, in a neighboring county, who’ve lived on the land they work for three generations. They don’t own the place. A rich man in Dallas owns it. In fact, over the years the ranch has been sold to various owners who keep it for a while as a tax write-off and then sell out to someone else. Each absentee owner has had the wisdom to keep the caretakers who’ve been on the place all these years. The men who’ve held title to the land haven’t really given a damn about it except as an investment. They haven’t known it the way J.B., the third-generation foreman, knows it, every blade of grass, every tree, every little run of erosion.

On paper, J.B.’s just a hired hand. But the fact is he can walk out on the grassy hill overlooking the stock tank, and he can say: this is the place where I was born and where generations of my family were born. My father and his father before him lie out in the cemetery. There I will go when my time comes. My children are here, and …

Well, the rest he cannot say, that his grandchildren and their grandchildren will be there. In fact, he knows that’s futile dreaming. But J.B. can say, in a profound manner of speaking, that this land, this house, this countryside are part of him, and he is part of them; and that in a spiritual sense they can neither be separated or exist one from the other.

It is spitting in the wind to think that Dallas will preserve the buildings of its past. We never have, and it’s hardly likely that we will start as long as the city continues to grow and attract new blood. The idea of preservation is anathema to our expansive character. It is like asking a strapping fellow in his boisterous prime to lie down and soak in a coffin of formaldehyde. In fact, it is damned near un-American.

Oh, I know. The Wilson Building ought to be spared the ball and hammer. It shouldn’t go the way of the Texas Building. I have said the same thing about other old landmarks which have bitten the dust. And if I were on any of the blue-haired committees which advise the city fathers, I would show my false teeth and growl if I saw anything other than a historical marker coming down on the dear, old bricks.

But it would do no good. Even if the other preservationists went along with me, the city would go ahead and let the owner of the property under question do with it what he wanted in the first place. And how can you blame the City Council? It’s easy to sit here and carp because they let some architectural relic be demolished but quite another thing, I think, to sit across the table from the owner of the old heap and tell him no, you cannot proceed with your multimillion-dollar plans to raise something in its place. When there comes a contest between values, money always wins out over sentiment. And when it is a tug-of-war between times, the living will always opt for the present and the future over the past.

The irony is that even our past speaks for the expendable.

We talk of Old Dallas as if it were still with us. The truth is that there is nothing but a timber or two left of the original village which cropped up around John Neely Bryan’s cabin. Not even the cabin of Bryan himself was spared the toll that new American generations exact of remnants. The cabin that is said to be his at the courthouse is a fake.

Besides, there was not one Old Dallas, but many, like Troy. The city over the years has gone through various character changes, even as a burgeoning metropolis, and yet few of the homes and buildings that distinguished those periods are left. We stand upon a rock midden, ruin upon ruin. What today is our new wonder tomorrow will be a heap of sand.

Even though I look longingly at the leftovers from the past and wish they could be saved, I can’t help but think that one of the signs of health in our culture is that even in our constructions, which are supposed to be inanimate, there is the animism of life, decay, death, and life again. Is it not a positive, rather than a negative, that the ground beneath some old edifice is more valuable than the building itself?

It struck me as hilariously ironic that the preservation people felt they had won a victory when they got the city to let them put a historical marker on a building that is due to be destroyed. How pathetic, and prophetic. It is like decorating an old soldier with great ceremony, then shooting him before a firing squad. As Frank Clifford pointed out in the Times Herald, the preservation ordinance is a laugh, its mock enforcement almost a clarion call to demolition, as more buildings have fallen than have been saved since its enactment.

I wasn’t being silly when I said preservation was almost anti-American. “The American journey has not ended,” the poet Archibald MacLeish wrote. “America is never accomplished, America is always still to be built. … West is a country in mind, and so eternal.”

We have always left things behind, traveled light, carrying only those things which were disposable. If something doesn’t suit us—a territory, a job, a house, a horse, a wagon, or a woman—we leave it and skedaddle in search of something new. Walls could not contain us, just as the past would not constrain us. Even if we threw up walls, we raised them tentatively, flimsily, like tent cities which were made to be broken down and packed away as soon as it was time to move on. Home may have been where you hung your hat, but it was mobile. The covered wagon became the trailer house, the chuck wagon the fast-food joint.

Not even the communities we paused to create were meant to last. The ghost towns were an American phenomenon. “It was enough to make them move if they saw they were not likely to prosper,” historian Daniel Boorstin wrote of our great-grandfathers. “They had come quickly and recently, and they could leave in just as short order.”

To paraphrase Boorstin, if our democracy was fast and rough, so was our technology. Haste caused us to make things no better than they had to be, so function and efficiency and obsolescence replaced art. Nothing was worth keeping if it didn’t work. Everything had to be portable and replaceable, literally everything.

Thus everything had a thinner life, even property. Land and buildings were not to be held for perpetuity, for future generations, but they became a commodity to be bought and sold at will. Deeds changed hands as fast as coin. Property was like the land and the people and the idiom of our tongues. Possessions, like the language itself, were mediums of exchange, not treasures to be kept. Nothing was solid, nothing sacred save for our faith in greener pastures. Everything was soluble and for sale. We became a throwaway, moveaway people, nomads more restless than Bedouins, harboring little unique except our incredible craving and capacity for change. And here on the Trinity, we are still at it.

Washington Irving looked upon it with some humor. “There is a certain relief in change,” he said, “even though it be from bad to worse; as I have found in travelling in a stagecoach, that it is often a comfort to shift one’s position and be bruised in a new place.”

Biologically, like all forms of life, it is quite natural for us to discard that which does not suit us. The snake sheds its skin, chickens molt. Marston Bates says that “Man, inescapably, is an animal, a part of the biosphere, a member of the complex of organisms that carry on the living process.”

Continuing in this vein, the biological analogue of a city is a community of organisms, a biotic town. This is not a base comparison. To describe Darwin’s theory of evolution as “survival of the fittest” is to dilute Darwin. The larger focus of natural selection is clearly one of mutual dependence, solidarity, and cooperation. There are, in the microscopic dazzle of our little finger, creatures who succeed to roles and habitat, who rise and fall as we and our environments do. If the new replaces the old in our biotic town, it is not simply a cruel and callous byplay but a direct result of a larger predilection basic to the survival of the community. There is a nexus of culture which binds us, and succession is a common and natural process. Naturalists tell me that we should not look at food chains as necessarily destructive and parasitical but as symbiotic, even if at the end of the chain is a master predator. Grass, deer, puma. Man is the ultimate predator, of course, but like the lion he is only a prince and not the king of the jungle. Nature is the king and has us. As some wag wrote:

Great fleas have little fleas upon their back to bite ’em,

And little fleas have lesser fleas, and so ad infinitum.

The great fleas themselves in turn have greater fleas to go on;

While these again have greater still, and greater still, and so on.

For every moth that is drowned in a pond or trapped in a spider’s web there are millions who make it to pollinate the flowers and please the eye. The flowers would not spring up without the rain, and the caterpillar would remain a wintry worm and never grow wings to fly if it were not for the sun. And if the caterpillar eats a lily to live, he will later make it up, and more, as a nectar-bearing butterfly flitting from flower to flower. Every death and life is a beginning. In natural history, symbiosis is more common than parasitism, parasitism more common than predation.

The fall of an old building, however grand, may not be the result of war among us, but evidence of the on-goingness of life, the tossing off of a magnificent but expendable old turtle shell.

If the building is dear to us, and some of us fight for its survival, it is because it has become part of the culture, which is supposed to be antithetical to nature. Jung said that culture lies outside the purpose of nature. But it seems to me that culture without the vitality of nature is a dead end, that if we follow it to its conclusion, we will end up lamenting like Joseph Wood Krutch when he said: “Ours is a lost cause and there is no place for us in the natural universe. But we are not, for all that, sorry to be human. We should rather die as men than live as animals.” Does that have to be the choice? Is to embrace civilization and art to deny life?

I can guess what some of you are thinking: that man long ago began separating himself from the natural world, that he lifted himself by means of his soul and his mind, his art, and now, for better or worse, his science. But I wonder. I especially wonder when I look at our cities, these places supposedly synonymous with civilization. They bear no resemblance to anything civil and humane, and neither do they look like any imitation of the natural habitat.

Edward Durell Stone looked around him and declared: “Everything betrays us as a bunch of catch-penny materialists devoted to a blatant sucking insistence on commercialism. If you look around you, and you give a damn, it makes you want to commit suicide.”

Loren Eiseley was repelled by this “new asphalt animal,” murderous and synthetic. He saw industrial man as an aberration in nature, the terrorist predator who kills not only to eat but to conquer. And Krutch, the naturalist, all but threw in the towel to the barbaric and naive, just as William Faulkner watched with horror as his Snopeses prevailed over his Sartorises. Krutch’s naive people are easier to take in their marauding appetite than Eiseley’s asphalt animals. One is naturally normal, the other is a fiend. I hope we turn out to be the former rather than the latter, that in our leveling march we are a force of nature and not some obscenity. I say this because if we are simply a simple, savage people, eventually we will develop the tragic faith that will sustain us … until we become so sophisticated that nothing matters.

It seems to me that our greatest art, and our highest soul-searching, brings us back to earth again not only to face the beauty and terror of life but to endure its incredible indifference to the values we so heroically, and pathetically, in our brief flurry wave.

Now Let’s Talk About It

By Melanie Ferguson

Porterfield began this piece with a realist’s laugh at how little we preserve of our city’s built landscape. His essay is no preservationist’s lament; he riffs on America’s increasing lack of attachment to place as well as Dallas real estate churn. “When it comes to a contest between values, money always wins out over sentiment,” he wrote.

No news there, Mr. Porterfield. Yet, his real lament is not for fleet-footed American mobility nor mere commercialism. It turns on a wistful question about nature in the city:

“I can guess what some of you are thinking: that man long ago began separating himself from the natural world, that he lifted himself by means of his soul and his mind, art, and now, for better or worse, his science. But I wonder. I especially wonder when I look at our cities, these places supposedly synonymous with civilization. They bear no resemblance to anything civil and humane, and neither do they look like any imitation of natural habitat.”

Porterfield may not have been a preservationist, and he certainly was no ecologist, but his 40-year-old essay still raises a question that we must ask ourselves as populations double and more of us flock to urban spaces: in what habitat do we land?

Melanie Ferguson is director of the Dallas Water Commons, a public-private partnership between the Dallas Wetlands Foundation, the City of Dallas Park and Recreation Department, and Dallas Water Utilities. Their goal is to build a public urban park that joins functionality with beauty, urban development with heightened awareness of natural resources, and water science with a natural gathering space. As the “Imagining Dallas” featured speaker at Dallas Institute, on May 25, she will curate a conversation about the nature of urban water.

This story originally appeared in the May issue of D Magazine with the headline, “Don’t Fear The Past.” Write to [email protected].