From June 2023

Robert Kent stops when he sees the bur oak. He stands with his arms akimbo and cranes his neck to stare up at the tree visible through a clearing in the forest. It towers 50 feet above us in a hidden stretch of southwest Dallas. “That’s gotta be 200 years old,” Kent says. A few more paces, and four more bur oaks, standing in single file, emerge. The outdoors seems to set him in constant motion, but he stops again. “That’s just incredible.”

The 36-year-old is the Texas state director for the Trust for Public Land, a nonprofit with branches in 28 states and the District of Columbia. His team of eight does what Dallas’ city government often doesn’t have the money or staff to do on its own: acquire land for parks and preserves and trails before it can be cleared for development. The Trust oversees master plans for ambitious trail projects and does smaller things with big impacts, such as working with Dallas ISD to transform school playgrounds into public parks.

“Every park that we have has a story,” Kent says. “Every property that is now conserved in a national forest or a national park, it was owned by somebody else before. There’s a history there.”

The stakes are high, for that history in our region has too often been one of environmental abuse or simple neglect. Weeks before our hike, Vistra Energy allowed a 50-year lease to lapse with the state of Texas so that it could sell Fairfield State Park. Dallas developer Todd Interests scooped up the 5,000 acres an hour south of town—though as D Magazine went to press, in early May, a bill had been introduced in Austin to effectively stop the sale. If the effort proves unsuccessful, land previously open to the public will become a private luxury lakefront community. Kent’s organization works to avoid similar outcomes for Dallas’ remaining natural areas. “Never let a good crisis go to waste,” he says, only half-joking about using the Fairfield headlines to gin up interest in the Trust’s mission.

Kent was hired to reopen the Trust’s Texas office here in 2014, after the outfit cut operations following the 2008 recession. Under his leadership, the Trust has saved 407 acres of green space in Dallas and more than 3,400 statewide. Since 2008, it has acquired land that now holds three new parks in Dallas, with another three in development. The Trust’s goal is for a park within a 10-minute walk from every home in America. In 2014, 54 percent of Dallas residents checked that box; nine years later, that number has grown to 73 percent, in large part due to the work of Kent and his colleagues.

“There are people every day working to shape the way that the city is built and the way land is conserved and protected,” he says.

Our April hike took us through the Trust’s next acquisition, the 282-acre Big Cedar Wilderness, not far from Joe Pool Lake. The owner, Liberty Bankers Life Insurance, has chosen to donate the $17.2 million property to the Trust rather than sell it to a developer. The Trust will give the land to the city. The City Council will soon vote to approve a $2.55 million payment to the Trust from its reforestation fund, which developers must pay into when they remove trees for their projects. Kent says a quarter of that will go back into developing the property.

As a private, nonprofit middleman, the Trust does administrative work for the city and can be flexible with what it pays. Local governments must offer the appraised rate for land purchases, but the Trust can buy for less, and the seller can credit the difference as a donation on its taxes.

Interstate 20 lies only a mile or so north, but, elevation aside, Big Cedar feels almost like the Ouachita Mountains in Western Arkansas. We’re surrounded by spindly juniper and lush pecan, oak, and cedar trees, shepherded along a narrow dirt path most often used by mountain bikers. (“Behind!”)

Kent has the look of the grown-up Eagle Scout that he is. He wears jeans, scuffed cowboy boots, clear-frame glasses, and a ball cap bearing the logo for the Trust. He dresses as if his day could take him from the nonprofit’s startup-bare office at Pegasus Plaza off Interstate 35 and into the woods, which it often does.

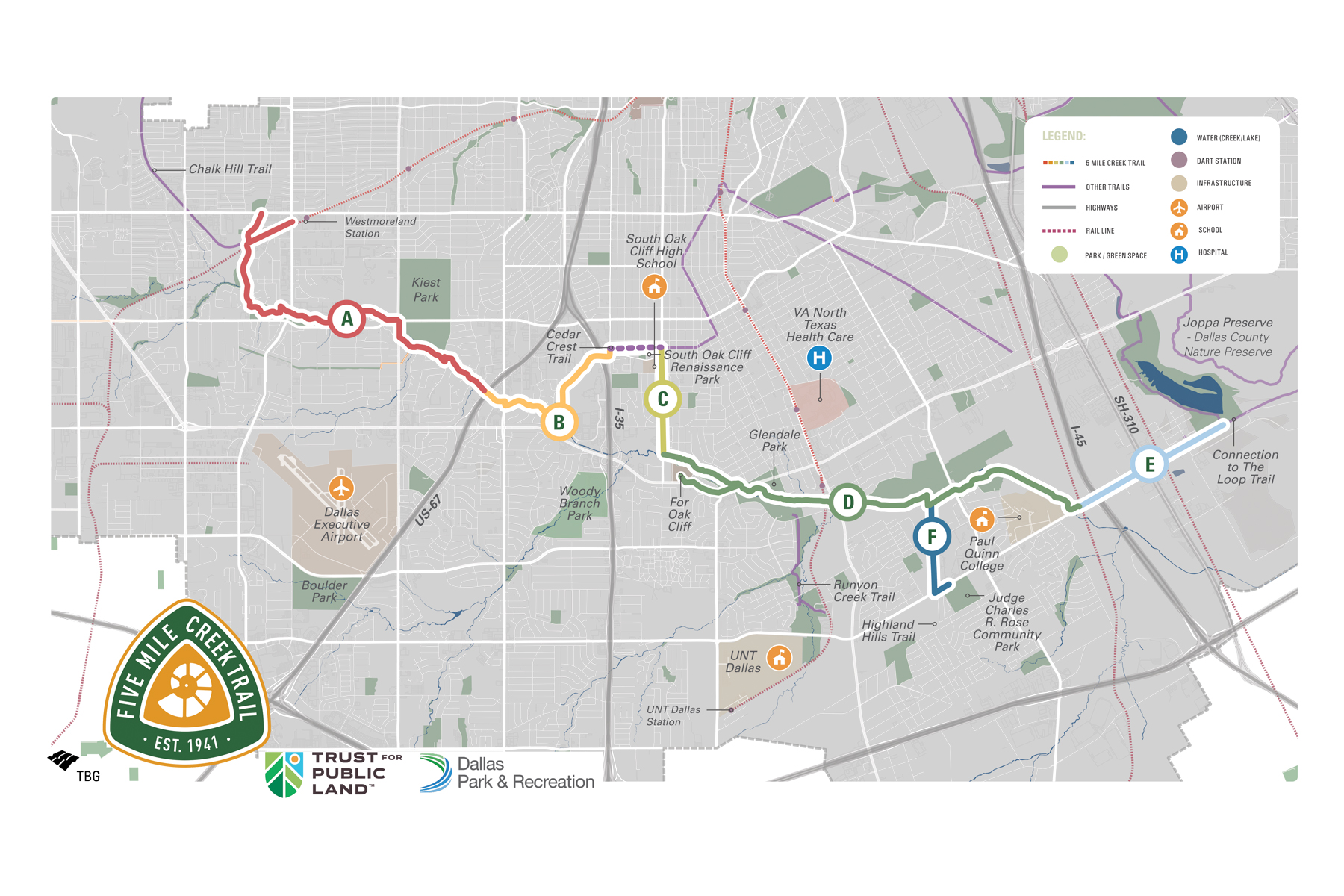

For the last few years, those woods have lined Five Mile Creek in southern Oak Cliff, a critical natural resource that drains water from about 70 square miles of Oak Cliff and southwest Dallas. It is the northern border of the Balcones Fault Zone, the same geographic escarpment that created the Hill Country. But unlike Central Texas, our sliver of paradise is largely inaccessible. The Trust oversaw a master plan for Five Mile Creek by the Dallas design firm TBG Partners. The Park and Recreation Department adopted the plan in 2019. This is the Trust’s most potentially transformative project yet, a trail spanning about 17 miles from the Westmoreland DART station all the way to the Great Trinity Forest, where it will tie into the under-construction 50-mile LOOP trail and connect with existing pedestrian infrastructure in the north.

The Trust for Public Land does what the city often doesn’t have the money or staff to do.

The trail along Five Mile Creek is important, but so are the parks that it will germinate. Already open is South Oak Cliff Renaissance Park, which transformed a 1.8-acre illegal dump on Overton Road, across from South Oak Cliff High School, into an LED-lit public space with a trail, a basketball court, a climbing boulder, wifi, and exercise equipment. Students at South Oak Cliff used to cut through the land littered with spent needles and trash to get to school. Some would meet in the brush to fight or cut class, says Derrick Battie, the high school’s community liaison. The park didn’t solve those problems, but it minimized them.

“When you bring something beautiful to a community, it’s going to be closely watched and closely monitored,” Battie says. “That’s the whole point.”

The coming months will bring the 40-acre Judge Charles R. Rose Park, near Paul Quinn College and UNT Dallas. After that, an 82-acre nature preserve called Woody Branch will replace what has for years been a dumping ground. It took three months for a contractor to remove 26 tons of tires and enough shingles to fill about 56 dump trucks.

The idea for these parks along Five Mile Creek is not new. George Kessler’s first comprehensive plan for Dallas, published in 1909, envisioned using creeks and green spaces as channels for development. “All the ideas in the Kessler plan really promote the connection to civic institutions, to public places, to green spaces, through greening pathways,” says Molly Plummer, the Trust’s landscape designer. With the exception of Turtle Creek, much of Kessler’s work was ignored.

Plummer started at the nonprofit as an intern, but her master’s thesis at UTA was about the Kessler plan and why so many of its ideas were never built. In fact, there was yet another plan that included Five Mile Creek, this one from 1944, but nothing happened then, either. Plummer is now helping Kent and the Trust bring Kessler’s vision to life.

Kent grew up in Lake Highlands, where, without even realizing it, he had access to the sort of linear green spaces that Kessler had imagined a century earlier. He would ride his bike about a mile through the neighborhood, eventually picking up the White Rock Creek Trail on his way down to the lake.

“That was such an expansive, eye-opening experience as a young person, to have agency over how you interact with the city and your neighborhood,” he says. “I can get on my bike, get on this trail, and be at White Rock Lake. That doesn’t feel that far away.”

Kent is the son of former state representative and Richardson ISD trustee Carol Kent and trial attorney David Kent. He went to Baylor for undergrad knowing he wanted to pursue some sort of public service. The idea was the World Bank or the United States Agency for International Development, helping bring economic development to low-income Central American countries. But he graduated in 2009, when government jobs were hard to find. Even after a scholarship-funded master’s program at the University of Glasgow, Kent was surfing couches in Washington, D.C. So he moved back to live with Mom and Dad.

He didn’t think his first post-grad job would be in Dallas, but he became the director of public policy for the North Texas Commission. He learned that cowboy boots and Wranglers—not his Jos. A. Bank suit—were the best uniform for getting small-town city managers to agree to put air quality monitors near parks. Three years later, the Trust called. They pitched him on reopening the Texas branch.

The first step was mapping what Kent calls “park deserts.” But park deserts are often park deserts because neighborhoods are full of houses, with no available land. But houses are near schools, and schools have playgrounds. The Trust was part of a consortium with the city, Dallas ISD, and the Texas Trees Foundation—another nonprofit with similar goals—to rebuild school playgrounds and open them up to the neighborhoods after hours. That’s a big reason why so many more Dallasites have a park within 10 minutes of where they live. Twenty have opened, and the Trust has targeted another 46.

Kent also saw something interesting that the Denver office of the Trust was doing. They would find land, appraise it and perform any due diligence, buy it with public grants and philanthropic dollars, help design a park, and then give it to the city for construction and operation.

“We didn’t have the staff to put that kind of focused energy into specific projects,” says Willis Winters, the former director of Dallas parks. Kent invited him to Denver, along with the president of the Park Board at the time, Bobby Abtahi. Winters retired in 2019. Winters says, “It was eye-opening to see it work so seamlessly and successfully.”

They re-created this model in Dallas, acquiring the land for the parks along Five Mile Creek. But it’s a failure if it doesn’t reflect what the neighborhood wants. Battie, the South Oak Cliff High liaison, remembers meeting Kent for the first time when planning got underway for Renaissance. “This guy had on a ball cap and a pair of cowboy boots,” he says, “I was just like, ‘Oh, boy, here we go.’ ”

But Kent and Plummer, the landscape designer, kept coming back. They kept listening. They attended neighborhood meetings. They helped build a steering committee made up of the school’s principal and alumni, the Marsalis Park Homeowners Association, the nonprofit For Oak Cliff, business owners, and clergy. That’s who picked the amenities that are now in Renaissance Park.

“ This is you guys’ part. We’re here to facilitate and teach you how to go through the process,” Battie remembers them saying. “And,” he says, “that’s exactly what they did.”

Kent compares raising money for Renaissance Park to “hand-to-hand combat,” where 25 donors helped fund a single $2.7 million park. Two years later, the organization has raised about $19.9 million for the entire Five Mile Creek project, with about a third of that coming from the Boone Family Foundation ($2.65 million) and Lyda Hill Philanthropies ($2.5 million). Since 2014, the Trust has raised $28.6 million; $20 million of that came from private donors.

Garrett Boone, co-founder of The Container Store and president of his namesake foundation, has given generously to the Trust. The 80-year-old was our hiking partner through Big Cedar, frequently whistling back and forth with birds that flittered in the treetops. Kent met Boone as an intern working at the Texas Business for Clean Air. The two would walk along the Trinity River levees, Kent astonished at how the city seemed to disappear. That’s the type of experience both men want more of in Dallas.

“It’s really dangerous for people to grow up without a connection to nature,” Boone says. “If we’re not connected to nature, we’ll never learn from nature.

“The beauty of Dallas,” he says, “is hidden in plain sight.”

This story originally appeared in the June issue of D Magazine with the headline, “The Land Man.” Write to [email protected].

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author