When ClubCorp CEO David “Pills” Pillsbury was 12 years old, he nearly burned down his family’s home. He had seen a janitor at his school mark a playing field by killing lines of grass with kerosene. Pillsbury and a friend tried the same technique to create a badminton court. But the boys lit the highly combustible fuel with a propane torch, triggering a wildfire on the 5-acre property.

“‘David! Goddammit! Call the fire department!’ my father shouted as he ran to the fire and I ran toward the house,” Pillsbury recalls. “I had to appear before the fire chief and make my case to avoid my parents having to pay $5,000 that they didn’t have to offset the cost of fighting the fire. Talk about pressure.”

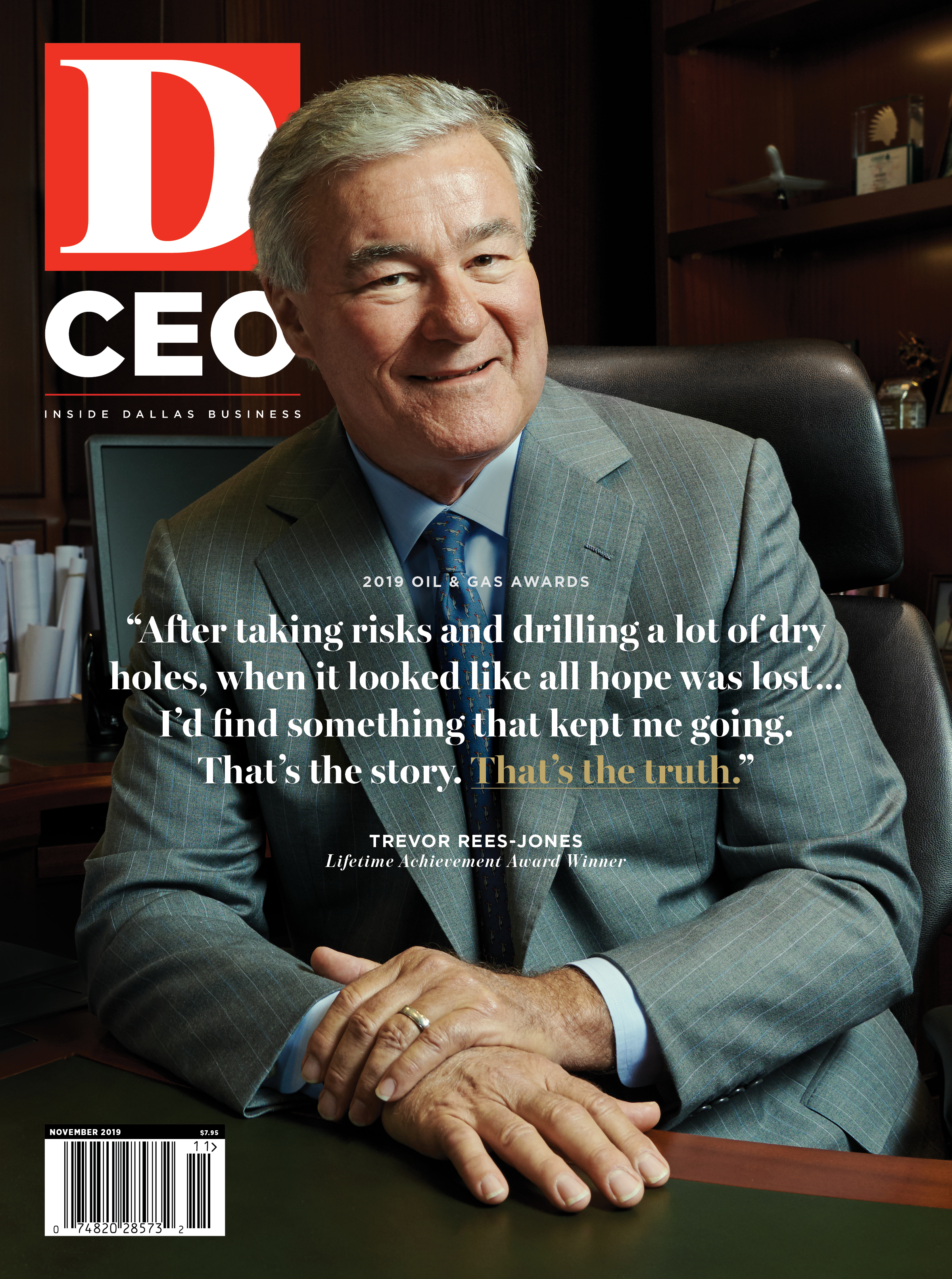

Somehow, Pillsbury convinced the chief to let him off. “It was one of my first presentations/negotiations—and without any leverage.” Luckily for the now 56-year-old executive, a trim 218-pound, 6-foot-4 man with a shaved head, not many of his projects have gone up in smoke.

Since taking the helm of ClubCorp in June 2018, Pillsbury has been building on the company’s strengths. Founded in Dallas 62 years ago by Robert H. Dedman, it owns more than 200 golf courses and 40 city clubs. But with the nation oversaturated with fairways, Pillsbury is adding events and other diversions. There’s also new predictive software to retain members, who have access to all company properties, made easy with the ClubLife reservation app. “Nobody’s doing this,” Pillsbury says. “There are apps for clubs, but not for 200 clubs.”

ClubCorp also is rolling out simulated golf concepts at many of its properties, after buying a controlling interest in the tech-powered entertainment company Big Shots. It plans to expand the concept to untried venues like shopping malls. And, ClubCorp is resurrecting a platform it forged decades ago at Florida State University: leasing football stadiums that go unused 357 days annually to create alumni and university clubs that operate year-round. It now has clubs in operation at The University of Texas, Baylor University, and Texas Tech, and four more in the pipeline, Pillsbury says.

Recognizing innovation and applying it system-wide is nothing new for Pillsbury. His first major career break came when he was a 22-year-old management trainee at CalGas. He discovered that a single employee in a tiny southern town was selling more than half of the company’s $69 home service contracts on propane appliance repairs. He traveled to Tylertown, Mississippi, and videotaped a good ol’ boy named Benny Hugh Gerald. The resulting tape detailed Gerald’s down-home approach. After shown to staff, sales jumped from 350 contracts a year to thousands, generating several million dollars in added revenue.

Pillsbury grasped that Gerald’s rural customers responded to authenticity and value for their dollar. “This was like the early stages of learning the power of teams and best practices,” he says. “You find somebody that’s doing something right, and you figure out how to disseminate it.”

By deftly deconstructing and communicating Gerald’s approach, Pillsbury came to the notice of the company’s CEO, who put him in touch with professors who were starting up an executive MBA program at the University of Southern California. Although the program was designed for mid-career executives in their 40s, they took on this promising 20-something, and his employer covered tuition.

There were other breaks, and some misdirection, in Pillsbury’s career trajectory. Three decades were spent at American Golf Corp. and the PGA Tour in a variety of roles, not to mention stints at Nike Golf, Mattel (marketing Hot Wheels cars), a Florida laser spine surgery center, and a Colorado craft brewer. While with the PGA Tour, all of his powers of persuasion were tapped to keep Donald Trump from making his Doral course crazy difficult—even for top competitors. He also talked Trump into restoring, instead of demolishing, the Miami course’s iconic fountain on the 18th hole. “For months afterward, almost every time I saw him, he reminded me that my idea cost him an extra $70,000.”

The job changes took a toll. Pillsbury is on his third marriage. Through it all, he figured out how to keep his five children from his first two marriages close; he convinced his first wife and her new husband to move from southern to northern California, from there to Oregon, and then to Florida, covering all the costs. “To make sure the five kids stayed together, I was never willing to move if it split them up,” Pillsbury says. “I always wanted my kids to be close, to be there for each other. Looking back, I now know it worked.”

Counter-Culture Childhood

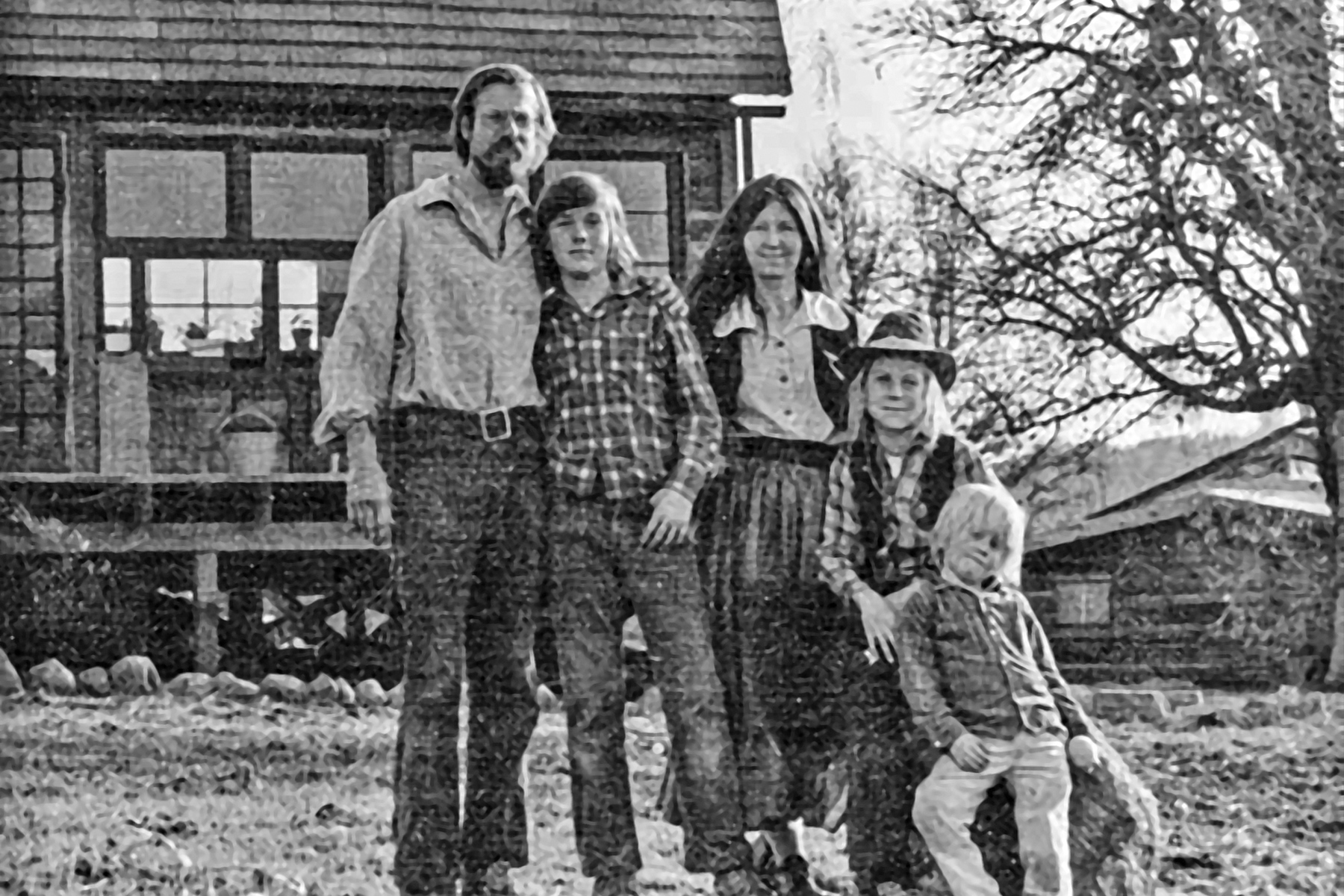

As for his own upbringing, “it was a magical childhood,” Pillsbury says. He grew up in Geneva, Kenya, New York City, and Detroit before spending a year in a clapped out, third-hand school bus with a jury-rigged second story. The family drove it west, looking not unlike the California-bound Joads in Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. But this was 1971, not the Dust Bowl ’30s, and poverty wasn’t forced on the middle class-fleeing Pillsburys. To no surprise, not everyone in Oregon House, Calif., (pop. 530) welcomed the “dirty hippies.” Shouting that epithet, a merchant chased a young Pillsbury—then with shoulder-length blond hair—and his shaggy-bearded father out of a store when they tried to buy the boy his first guitar. Through such encounters, Pillsbury learned how to navigate different cultures and unwind sudden-sprung situations, lessons that have marked his life.

His parents met in North Texas. His father, Peter Pillsbury Sr., grew up in Farmers Branch and attended what today is the University of North Texas. His Georgia-born mother, Cindy, was a Braniff International Airways flight attendant. After his father earned a masters in divinity from Princeton Theological Seminary, the Presbyterian mission board dispatched him to newly independent Kenya. Later, he became more community organizer than conventional cleric in Detroit, inspired by the charismatic advocate for the poor, Saul Alinsky, and parted company with the church. But his self-published memoir, Journey to Sunshine Mountain, reflects a man with a deeply felt and well utilized moral compass.

Peter Sr. and Cindy eventually dropped out, embracing the non-materialistic counter-culture. They considered settling in Alaska or Mexico before seeing an ad for 5-acre mountainside homesteads in Oregon House, an unincorporated, former stagecoach stop 70 miles north of Sacramento. “We believed that we could create a life … that was not exploitative of others, that exuded peace and love, that was in harmony with nature and that supported traditional American values of individualism, pioneering, hard work, and cooperation,” Pillsbury’s father wrote.

The rural newcomers pursued that dream with no farming or home construction skills. (Later, both parents became educators, with Pillsbury’s father ultimately retiring as a superintendent.) For years, the family had no electricity and used an outhouse. But they could take hot baths: A propane-flame under the cast-iron tub heated the water—to such a scalding degree that wooden planking kept everyone’s bottoms from charring. A goat provided milk. Bread was baked in a wood-fired oven from wheat that Pillsbury’s mother hand-milled. Pillsbury went to school in American-flag bell-bottoms that she sewed. Money was tight.

“We literally went out to dinner two times a year,” Pillsbury says. “I remember one year ordering fried shrimp, which was probably frozen and thrown in a deep fryer, and I thought it was the best thing I had ever had.” He and his older brother, Peter Jr., saved up quarters to blow on the local diner’s pancakes—made from white flour, a rare treat. Electricity arrived when Pillsbury was 12, and the brothers spent their savings on a tiny, second hand TV with rabbit ear antennas.

Pillsbury “worked every weekend clearing, wood cutting, building fences, irrigation, you name it,” he says. “As I got older and more involved in sports, I was required to do much less at home. Maybe that’s why I loved sports so much.” He gave up on baseball (“I couldn’t throw a curve ball”) but excelled at football. Out of the blue, another member of the squad suggested they pair up as debaters. Applying themselves, the two became state champions. The University of California-Davis dangled no football (or debating) scholarship, but promised Pillsbury a job with an inflated salary if he played; UC-Berkeley offered a free ride, which he took.

His father’s son, Pillsbury was disturbed to see fellow players, especially those from impoverished, minority backgrounds, given the false hope of an NFL future with no support to succeed academically. Half of his recruitment class flunked out. His own financial aid worked out to 80 cents an hour, based on what he put into training and playing. “Wait a minute, this isn’t making sense,” thought Pillsbury, who began agitating for a student-athlete’s union, decades ahead of its time and hitting a nerve. Somehow, Newsweek got wind of it, and ran a small item quoting him by name. Unamused, Cal’s athletic department made clear his scholarship would disappear if he persisted.

“The system reinforced the wrong priorities,” Pillsbury says. “I couldn’t afford to lose the scholarship. I decided to play along.” By then, British-born kicker Mick Luckhurst had spotted the player with locks that flowed out of the back of his helmet. Noticing Pillsbury’s drive, he told coaches: “See that kid over there? I want him on the kickoff team.” Luckhurst, who went on to play for the Atlanta Falcons, says “Pills” was the tip of breaking wedges against the opposing team on kickoffs. “He was the best at it,” Luckhurst says. Although Pillsbury wasn’t a quarterback, the team recognized his leadership skills and elected him co-captain.

Challenging the Status Quo

Pillsbury had come a long way from his Oregon House upbringing by the time he graduated from college. But there were still rough edges when he joined the American Golf Corp. in 1988, recalls Joe Guerra, a business school classmate who would later serve as co-CEO of the huge golf course company. Pillsbury, he says, would do things like take any place in a plane’s first section, not realizing seats were assigned, recalls Guerra. “I always wondered if that stemmed from growing up in a bus or rural America. He didn’t know ‘the rules.’”

The emerging executive quickly caught on, but kept traits that would serve him well. His upbringing “allowed Pillsbury to size up a situation differently” and “break norms as necessary,” Guerra says. “If it’s not broken, he’s not going to fix it … but he’ll challenge the status quo.”

What sets Pillsbury apart is that he is driven by many other things beyond business, Guerra says. “He’s not thinking like a typical CEO. ‘Thinking out of the box’ is a cliché, but he really does. And he’s not afraid to say, ‘It doesn’t work.’ But to Pillsbury, if you launch five arrows at a target, you have a better probability of winning.”

Guerra recalls watching his former colleague talk down a club house full of members—emboldened by “liquid courage” and angry that their upscale course in Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, had just been sold to American Golf, which ran both posh clubs and bare-bones public courses. “We had a crisis; 350 of the 400 members said they were leaving,” Guerra says. Pillsbury told them they had nothing to lose by staying to watch if his company actually fulfilled promises to enhance service levels and make major improvements. “He’s skilled at handling adversity—and we kept every single one of them,” Guerra says.

Pillsbury was approached by ClubCorp as a potential CEO candidate in 2017. Then, crickets. He had been eager to return to the golf industry, but was baffled by two months of unreturned calls. As it turned out, the publicly traded corporation was in a quiet period as Apollo Global Management was finalizing its acquisition. After the sale, Pillsbury approached Apollo about serving as a board member or a consultant. But the private equity giant told him it wasn’t making any changes. Then months later, he was offered the top job.

Pillsbury found that the nation’s largest golf course owner had overly “homogenized” the clubs. But before he could effect much change, a spectacularly wet winter kept links unplayed 20 percent of the time, more often than not on weekends, when both the grounds and the clubhouses are fully staffed—a double whammy.

Pillsbury believes Apollo is transformational. “I didn’t have any interest in just having your ‘grandfather’s private club’ model,” he says. “What we’re doing is broadening the appeal of our offering to be more of a lifestyle company. … And that’s about wellness, fitness, and racket sports and aquatics, and within that it’s about food, it’s about wine…”

Reducing membership churn is key. Toward that end, ClubCorp hired a developer to build a predictive analytics platform. Launched this summer, ARMI (an acronym for at-risk member intervention) predicts eight months in advance whether a member is likely to leave. Employees pick up a phone to personally invite these members to an event ARMI says they’d be open to—a wine tasting, a golf clinic, or a dinner with a celebrity speaker. “It’s incumbent on us to provide the programming that keeps you engaged,” Pillsbury says. “That’s a paradigm shift.”

University Appeal

Among ClubCorp’s growth strategies: opening new venues at college football stadiums.

Florida State UniversityrnUniversity Center Club in Tallahassee was the first college property ClubCorp opened. It occupies 64,000 square feet on three-and-a-half floors in FSU’s Doak Campbell Stadium.

The University of TexasrnThe University of Texas Club on the east side of Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium was recently given a multimillion-dollar spruce-up. Its private rooms can accommodate 300 guests.

Mission Hills Country ClubrnOne of the most prestigious clubs in California’s Coachella Valley, Mission Hills offers three championships golf courses, as well as nationally ranked tennis and croquet facilities.