Some of the girls got fed up with waiting for Howard to appear and left. Others arrived just in time for the third meeting and got hired without having been at the previous two. At the training session, we were given a list of drink prices, taught how to use a tip tray, and told by Bray that our tips would improve if we gave male customers “just a hint or a hope that you might go home with them.” We were introduced to Barbara Adair, the backstage waitress, who was exhibited as The Successful Cocktail Pro, but Bray and Howard never gave us the chance to ask her any questions. As she sat there in an overstuffed Spanish-American-style chair, she reminded me of a waving, smiling, self-satisfied beauty queen on a tissue-paper float gliding in a parade.

When the meeting adjourned, Howard called us up one at a time and placed us on the schedule. The first thing he said to me was “Can you come tonight at 7?” He was already writing the date and a number 7 down by my name.

“Tonight!” I tried not to seem hysterical.

“Otherwise, I can’t get you on until next week,” he said looking up only as high as my hands wringing nervously and fumbling around with the edge of the table. Okay, I said, sounds just fine.

• • •

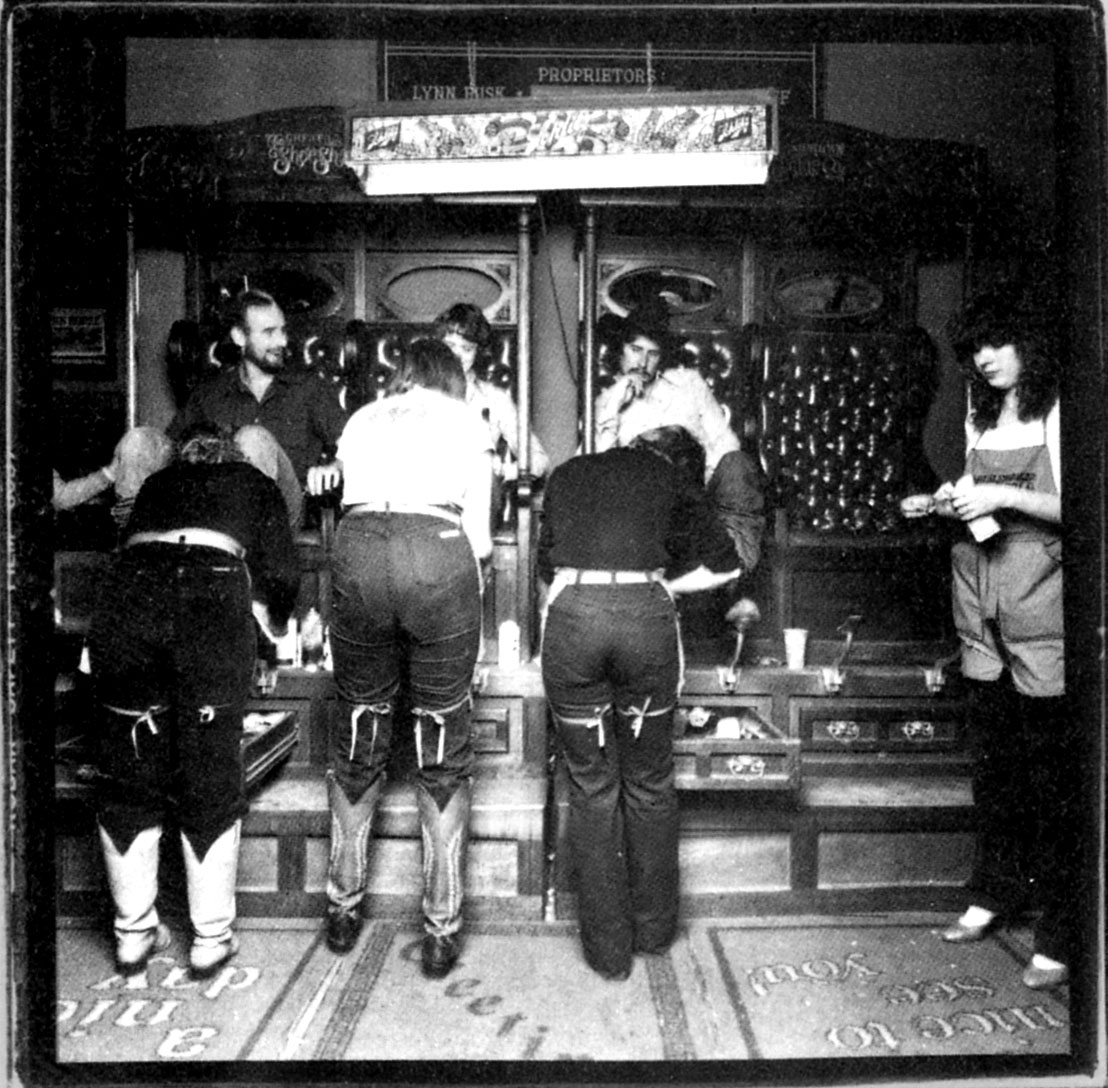

The people working at Billy Bob’s are a little like show people, and they’re at their showiest before going “on,” when they’re behind ominous-looking doors marked EMPLOYEES. The long, high hall extending out beyond the receptionist’s desk gets congested with folks around six o’clock on weekend nights, and for an hour or so, until everyone is assigned a section, it’s like a big, boisterous cocktail party — except no one’s allowed to drink. The security guards (or bouncers) are always big guys, usually weighing well over 200 pounds, and their bodies look as big as mattresses next to the fragile frames of the little waitresses tottering on high heels, holding their serving trays before them like shields. Some of the girls have the faces of angels with features as fine as the feathers in their hair. Others have faces like topographical maps of the Southwest with lines as long as rivers and crevices just as deep. Character actresses in heavy stage makeup — only they’re not acting, they’re for real.

The tension in the back room mounts when the department managers begin to pace back and forth with walkie-talkies pressed to their mouths or their ears. Ahhhh, this is Charlessszzzzpt. Don, are you near the vault? sszzzzpt. And there is a constant current of conversation over the noise of people slamming locker doors and punching in. Casual chatter, shared bits of household melodrama, desperation, little dreams.

All the voices accumulate until the pressure within the employees’ section is so great that it stabilizes the pressure being sensed from outside, and whoosh! the managers delegate their workers to specific sections. Finally we spill out to, as Bray once said, “serve the masses,” leaving peace and quiet in our wake.

On my first night of waitressing, I was assigned a section of tables containing 72 seats, all of which were open to the public. Reserved-seat sections often contain higher tippers; the waitresses with the greatest seniority, the highest heels, or the sexiest hairdos are stationed there. I opted for comfort that night and wore construction boots. Thusly, I was no glamorous babe my first night at Billy Bob’s, and my section seemed to suit me well. I think it could be best described as roughly equivalent to the area for “groundlings,” the penny-a-seaters, at the Globe during Shakespeare’s time. But I had to hand it to them: Those people could consume. I spent much of my time taking used nacho trays and popcorn bins off sticky tables. The line for drinks at the waitress station was so long that it sometimes took up to 15 minutes to get service, and I had yet to learn how to alternate the other bartenders working up and down the aisles. At one point, I returned with an order only to find that the customers had walked up to the bar and purchased drinks for themselves. On another occasion, I delivered six Lone Stars to a table while the man who’d ordered them happened to be in the men’s room. “He’ll be right back,” his wife said. I made a mental note to pick up the $9 due and then forgot about it; one foul-up like that can ruin a waitress’ night.

I had all the wrong answers and none of the right comebacks. One customer put his arm around my neck (the music was always so loud, I had to hunch over to hear) and said, “Tell me this, hon, do ya’ll have hurricanes?” Assuming he was one of the countless conventioneers, I thought a moment, then said that I knew we had tornados, but that I didn’t think hurricanes ever came this far north. He had meant the drink, not the phenomenon.

People don’t really drift in and out of Billy Bob’s. When they come in, they’re usually there for the night. That means they might sit in the same chair for six or eight hours, and that means they’ll most assuredly get drunk. Confusing orders from drunks were excruciating things to organize. “Okay, ’nother Bud,” would be a typical beginning followed by, “Charlie, what are you drinking? Okay, that Bud and then a Weller and Coke, then ahhhh … ’nother Bud, a Coors Light, what’s that? A Bud. That’s three, four more Bud, a margarita. A Miller Lite, ’nother Lite, and one more Bud; that’s three, four, five Bud. Oh, and she wants that Weller and Coke in a large glass.” I’d be writing all this down fast and furiously, then on my way down the aisle to the waitress station, I’d get caught by someone complaining that their gin and tonic didn’t have a lime. As a rule, all the limes were stocked at the 16 bars near the front of the club, as many as 95 paces away.

Within two hours, my healthy, happy section had thinned down to a small number of discontented drunks needing cigarettes and service much faster than I was capable of giving it. When Brenda Lee sang “I’m sorry, so sorry” that night, I commiserated.

Things settled down about 1 a.m., after the last rodeo show in the bull arena, and I had the time to wipe down one table and listen to a conversation between two men in their 20s sitting about 8 feet away.

“You know, that girl looks like a schoolteacher.”

“Uhmph, yeah. Short hair.”

They were talking about me.

I retreated to the waitress station and considered adding a wig and a padded bra to my expense account. Later, in the ladies’ room, I gave myself a thorough once-over. Even in my shirt still stiff from the hanger at Cutter Bill’s, I looked too much like a woman bent on a career. In the four years since I’d graduated from college, I’d cultivated a no-frills, let’s-battle-this-out-in-the-board-room-boys look that worked well in Dallas but was failing miserably here. In looking around the club at the best waitresses — the girls that made more than $90 on a good night — I noticed that they all carried a magical kind of confidence, a sensuality that I would have to imitate if I hoped to do well.

Every Saturday night (actually 2 a.m. Sunday), after the sounding of “last call for alcohol,” and after the customary playing of “Your Place or Mine?” the waitresses were responsible for “breaking the club down” from Phase IV to Phase II. This means that after cleaning our own sections, we were obligated to disassemble dozens of folding banquet tables and stack hundreds of chairs to make room for the stage’s advancement about 40 yards deeper into the club. That way the club could economize by using only a portion of its available space during the week. I’d been warned ahead of time that “breaking the club down freaks the new girls out,” but I wasn’t prepared for the kind of work we actually had to do. Some of the girls got pretty good at disappearing into the ladies’ room around table-disassembling time. They soon found out that their lazy ways were doing more harm than good; getting ostracized meant that no one would help you if you got in a tight spot.

• • •

My second night of work fell on a Friday. Jerry Lee Lewis failed to pack the house. This was the first night of work for Jeannie, Connie, and Tammy, my friends from the training sessions. They were jittery and apprehensive; I, on the other hand, had vowed to be more approachable and carefree, less stuck-up and scared. Unfortunately, I was assigned to a section of reserved seats that went unsold all night. Don Howard came by the waitress station at 10:30, collected the starting bank of $20 he’d given me, and told about seven of us that we could go home. For the girls paying $2.50-an-hour for baby sitters, a night like that is a money-losing proposition. Disastrous.

But when I met Jeannie by the lockers in the back hall she seemed relieved that she was getting to slip away. I asked her to have a drink with me. No, she said, she needed to get home. Please, I said, just one.

A few minutes later, with our coats falling backwards and inside-out over the bar stools, Jeannie and I were sitting up straight with our elbows on the rail.

The bulk of our time, that 95 percent, seemed so loathsome because it consisted almost entirely of, in the waitresses’ vernacular, “taking shit.”

She told me her husband drove a truck. They had a 12-year-old daughter. Jeannie had a clerical day job with a computer programming firm. Her husband had left her a few years ago and moved to Mississippi. “I was just getting used to being on my own,” she said, “when he came back, and I wasn’t ready for him to come back. I wasn’t ready for him to come back at all.”

She didn’t like this waitressing job already, she said. Too much noise. “I was thinking I could do it, but I’m not so sure now if this is for me.” I walked to her car, suspecting I’d never see her again.

Back in the club, thinking I hadn’t gotten much out of my first covert interview, I bought a slice of pizza and walked down toward the stage where Jerry Lee was in full-tilt — banging on the piano keys with his feet, his elbows, and the backs of his thighs. He slid up and down the keyboard as if he were on skis.

Mesmerized, I chomped down on the last bit of crust, glanced to my left, and noticed a tall man standing confidently with one hand resting on the reserved-seat rail. He’d been pointed out to me before. It was Billy Bob. Billy Bob. Standing there with a glass in his hand, chewing ice cubes, just watching.

• • •

What began to disturb me about this secret project was the effect it was having upon the rest of my life. Standing in line at the grocery store skimming magazines, calling in to my Dallas office for messages, carrying on conversations with friends — suddenly everything seemed lackluster. But at Billy Bob’s, there were big-name acts on stage, drunks waving their hands in the air for service, big feelings, big crises, booming music, fights, people practically fornicating on the floor. All from just existing, just from being there. Dodging people in the aisle, obsessed with my mission: delivering drinks.

“Two Weller and Coke. One scotch and water. One bourbon and water. A Bud. Two Lone Star. A Lite and a draw.”

It was poetry. And you never knew when you were about to make a big score. It happened when you least expected it. Nothing was predetermined. Nothing was truly under your control. A man might roll out a $50 bill for a single drink. Keep it. Keep it. One of the bartenders told me that Billy Bob gave her a $100 bill once for bringing him a $10 roll of quarters. Another waitress received half a torn $100 bill when she delivered a man’s first 7-Up; he gave her the other half at the evening’s end. When she got home, she said, she very carefully taped the two halves together and stared into the face of the bill for a long, long time. Something like that happened to everyone at one time or another. What you had to do was forget about it happening. Then it would come. Keep it. Big money thrown into your face for nothing except all the time you’d put in getting stiffed and pretending you didn’t care. Here baby, it’s yours. You deserve it.

George Bray had warned us that 95 percent of our time would be spent preparing to make money. I figured that only one-hundredth of the remaining 5 percent was when the big tips came, the other 4.99 percent resulted in small bills or quarters, depending upon how capable you were. But the bulk of our time, that 95 percent, seemed so loathsome because it consisted almost entirely of, in the waitresses’ vernacular, “taking shit.” Bowing down to the assigning manager, bowing down to the head waitresses, bowing down to the customer. Waitressing is smiling when someone jerks you violently by the arm and says in the surliest of sneers “bring me another shot of Jack.” It’s smiling when the manager moves you to another section that you know he knows no one wants. It’s smiling when another waitress who has absorbed her share of grief for the day says, “Hey, I was waiting here before you.”

“Not taking any shit” is a waitress’ crusade, and it’s the subject of most of their conversations. Despite that, it continues to come in from all sides, perhaps because they fight it laterally instead of rising above.

Once I was watching the spotlight operators climb to their posts before the first of two Roy Clark shows when a waitress named Candy materialized behind me and wanted to talk.

“Something’s wrong with my damn transmission,” she said. “I called AAMCO this morning, and they towed my car to the shop for a free estimate. You know, if it’s free, I figured, why not? And if I don’t like the estimate they give me, I’m going to take it somewhere else.”

I said something like, “That sounds wise.”

“I’m going to say that the price sounds unreasonable,” she went on, “and then I’m going to take the car somewhere else, that is, if I don’t think the first price is fair. I’m getting pretty cranky in my old age…”

“Well, yeah. It happens.” I really wasn’t paying much attention to her. A man on stage was communicating with the light operators through earphones.

“I’m sick, just sick of letting people take advantage of me, you know? And I’ve decided that I’m not going to take any shit from people any more. People will walk all over you if you let them, and I’m just not going to take it any more. You know, enough is enough. Right? I’m no dummy. I’ve just decided ’no more.’” No more.

We didn’t speak for a few moments. Then suddenly she said, “Last night I was so mad at my ex-husband that I threw my boots at him, and they made two dents in the apartment wall.”

I said, “I thought you weren’t going to take any shit any more.”

“Yeah, yeah. He’s real bad news. He’s nuts. And I married him twice.”

• • •

Author