What’s permanent are the people ready to fill the places left by those who disappear. It’s not even the people or the place that will endure then, it’s the predicament: cocktail waitressing, an indentured bondage. Servitude for spare change. It’s based on the concept that if you smile and act humble before faceless strangers when you bring them their drinks, they’ll leave extra money on your tray.

It is a job many women find degrading. It is not a job for which our culture reserves a great amount of social esteem; nor is the title “waitress” one that many women would want etched on their tombstones. But when I report for work each night at Billy Bob’s Texas, I have to deal with another term. Imposter. Perhaps even “fraud.” I was, as they say in B movies, not really a waitress. I am a journalist; perhaps a voyeur as well. I was out to see life on the other side of town, to experience a foreign world, and then return to my safe, secure, white-collar world to write about it.

Thinking this, holding on to these racing thoughts, afraid I might lose them all if I didn’t tie them down, I turned to Tammy. She was clapping her hands, swinging her hips from side to side, periodically throwing her dark hair over one shoulder. Her eyes brightened, and she shouted something I couldn’t hear over the music. I leaned close enough to feel her breath in my ear.

“They’re great!” was all she was saying.

I hadn’t been listening.

• • •

From Fort Worth’s Main Street, Billy Bob’s Texas has the institutional look of a museum or a monument on the scale of something you might see in Washington, D.C. This is not to say it is an attractive place from the inside or the out. It’s not. There is a falseness to the painted adobe-toned concrete and a Disneyland look to the building’s restored exterior. There isn’t any greenery or landscaping to speak of around the 127,000-square-foot structure. A garish Billy Bob’s Texas marquee looms above the four-lane street telling passers-by in no unsubtle terms about the live entertainment of the week. Flags of Texas are staggered across the honky-tonk’s roof, and special speakers transmit country music into the lot to pacify the people waiting for tickets. Sometimes management forgets to turn the speakers off, and the music murmurs on all night spewing melancholia.

The building once housed a Cook’s Discount Store. Before that it was used during the Fort Worth Fat Stock Show. The stockyards lie just behind the club, close enough to enfold the building in a cloud of pig and steer smells when the wind is right. During the day, the enormous front lot is spotted with the old trucks and cars of a few employees, but at dusk the place takes on a pulsating vitality. It becomes a rumbling, puffing, and blinking throb as if the surrounding property were one trembling engine, one big machine.

Mickey Gilley ain’t got nothing over Fort Worth now that Billy Bob’s Texas is the biggest, baddest honky-tonk in the world.

When Billy Bob Barnett, a well-moneyed Lampasas native, and his entourage of interested investors decided to build a nightclub that would outdo Mickey Gilley’s famous establishment in Houston, they relied most upon the know-how and venture capital of Fort Worth nightclub magnate Spencer Taylor. What they built was the ultimate in Texas overstatement.

40 bar stations. Count ’em. 40. A 30,000-square-foot dance floor. A 48-by-22-foot stage for live acts. A real rodeo ring with bleacher seats for 500. No mechanical bulls; real bulls. A private club for VIPs. A dry-goods souvenir store. Twenty-three pool tables. Pretty girls giving sexy shoeshines. An oyster bar and a pizza place. Video games. Portrait studios. Popcorn stands. No one has ever seen anything like it. People will flock to it from all parts of the world.

No one’s saying how much either Barnett or Taylor and the other partners have sunk into the bottomless pit of a project. Suffice it to say that few cities outside Texas could support another country and western nightclub in a heavily clubbed part of town more than a year after Urban Cowboy was released, just when country was starting to seem “uncool.” Maybe Billy Bob’s Texas is a testament to the Fort Worth ego or the egos of its native sons. Surely the biggest honky-tonk in the world means more to its owners than the dollars and cents that went into it. But maybe not; maybe it’s just the biggest, brashest nightclub money-making scam to ever hit the Guinness Book of Records. One thing is certain: If disco is out and country and western is well on the wane, people will still be honky-tonking someway, somehow. The people running Billy Bob’s are banking on that.

The club has four “phases,” so it won’t seem empty if only a thousand people come out some night. Phase I is when the front bars and the dry-goods store are the only things running. Phase II is when recorded music is being played and the club is host to up to 2,000 people. Phase III is when a live band is on stage. Phase IV accommodates 6,500 people and is like a candle flaming at both ends: rodeo, jewelry store, restaurants, pinball and video games, even portrait artists to immortalize you in chalk and paper, so you’ll never forget what you looked like at the precise moment you were there.

It’s hard to describe the size and scope of Billy Bob’s Texas in words without resorting to cartoonish expressions like Powwww! and Whammmm! It is a rush just to walk into the place. Whhhhooppp! It swallows you up at once. Big as an airport. So dark and cavernous that you find yourself checking for bats. And music — loud music — blaring from speakers standing as high as houses.

And it’s the illusion of strength, this idea that biggest means best, that attracts dozens of employee applicants every week. The jobs that are perpetually open are for cocktail waitresses. No experience necessary. For your time, you get $2.01 an hour and whatever you can wrangle for yourself in tips.

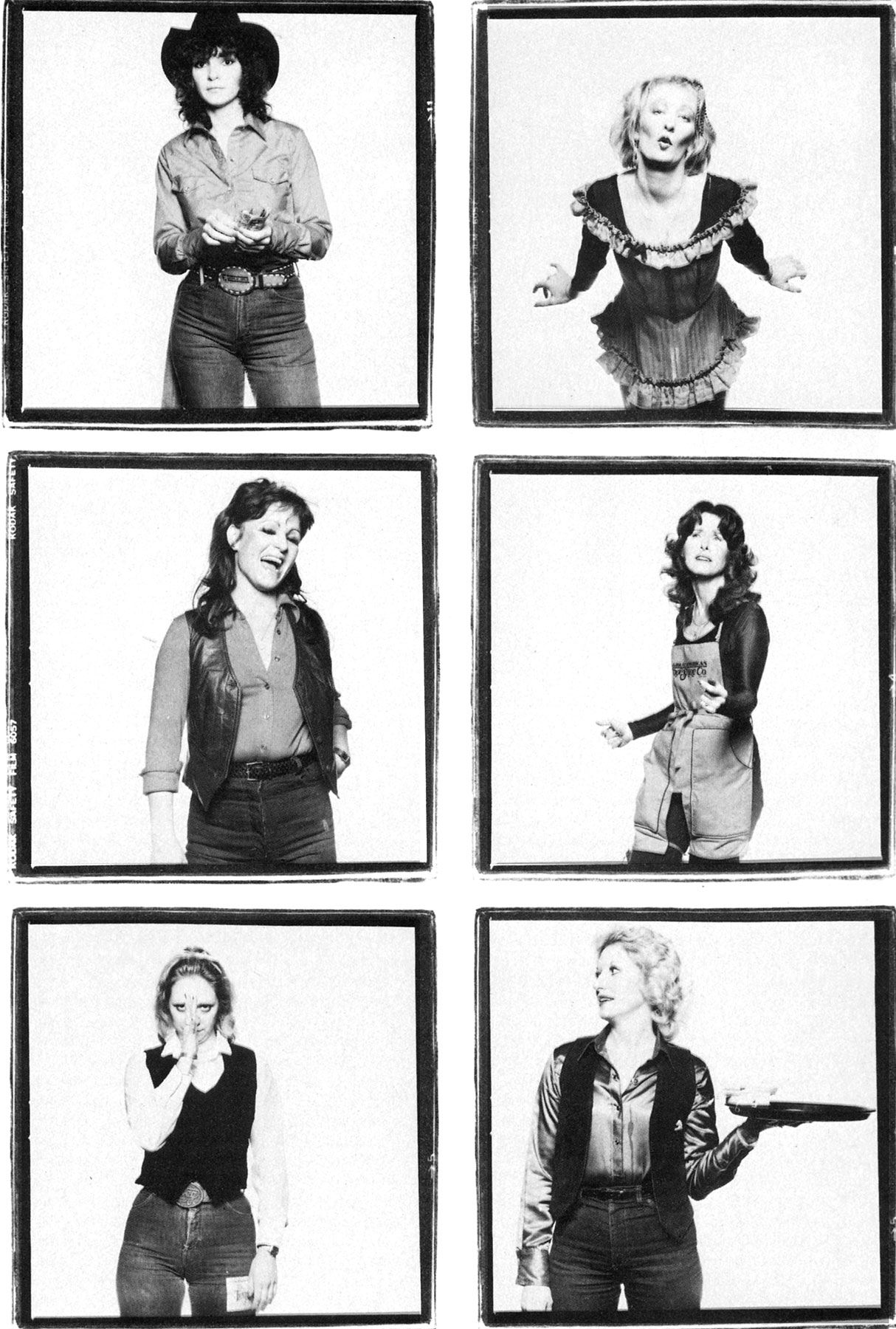

I remember turning in front of the full-length mirror in my Dallas apartment an hour and 15 minutes before I was due in Fort Worth for what I thought was to be my waitressing interview. Something about the costume was wrong. I was wearing my own jeans, an oxford-cloth shirt bearing the nametag of my brother’s prep school roommate, Frye boots, and a borrowed doeskin jacket that smothered me in fringe. I changed shirts. Still bad. I jogged to the medicine cabinet and found an old tube of Mary Kay eyeliner sealed with a scab of its own contents. I brushed on some mascara, too. Improving some, but still all wrong.

The problem, I decided when I glanced into my car’s rearview mirror and saw the top of my head, was with my hair. The short haircut comes from Neiman’s and is, in my mother’s words, “smart.” I didn’t think smarts were going to be what I’d need.

My looks didn’t matter, as it turned out. My being reared in Chicago didn’t matter, and the mysterious three-year gap in my employment record from 1978 to the present didn’t matter, either. What you do to get a job at Billy Bob’s is wait, however patiently and as long as it takes.

I found Don Howard, the man who hires and fires all waitresses, at the designated hour in the VIP Room, a bar within a bar for people who pay a $300 annual membership fee. The VIP Room is the site of most of Billy Bob’s parties, public and private; it’s the only part of the club except backstage in which you can be somebody or do something to garner attention. If you dance on a table or yodel real loud in Billy Bob’s proper, you’re apt to get ignored; in the VIP Room, you’ll get laughed at. So there Howard was in the VIP Room being cool. A slight man with coarse whiskers, Howard always wore a black hat, jeans, and a Western-cut corduroy sport coat. He surveyed me brusquely from under his hat and asked me to take a seat in the management office, an outer holding cell trimmed in chocolate-colored paint that was chipped in several places where office chairs had hit the walls. I took a chair beside a heavy-set waitressing applicant who introduced herself as Jeannie. For 15 minutes or so, we sat quietly, watching the telephone receptionist punch blinking red buttons and listening to her say “Billy Bob’s Texas… Jerry Max Lane and the Hill City Cowboy Band… $3 for men, $5 per couple… Unescorted ladies get in free…” in a lyrical little country voice, over and over.

It’s hard to describe the size and scope of Billy Bob’s Texas in words without resorting to cartoonish expressions.

Every minute or so, someone would burst through the door on the left-hand side of the small room, step over our feet and into the next corridor. Howard strode through six times, clomping his boots heavily with a gait that was obviously calculated to display superiority. Each time, Jeannie and I sat up straighter and looked as though we were ready to be spoken to. Howard never acknowledged us, but it was clear he knew we were there.

“There he goes again,” Jeannie whispered after Howard had passed us by for the fifth time. “Sure is a lot of coming and going here. Busy!”

A well-tanned, dark-haired man swaggered into the room wearing a classy looking brown suede sport coat. The man stopped at the desk and rifled through some messages, then left the room.

“Wasn’t he a nice looking man!” Jeannie said in a grandmotherly voice with a didn’t-you-think-so curled onto the end.

“That was Spencer Taylor,” the receptionist said as she shifted the mouthpiece beneath her chin. “Whoops, hold on.” Buzzz. Click. “Billy Bob’s Texas.”

Howard suddenly rematerialized. All told, we’d been waiting about 20 minutes. “Read this,” he said, handing me a Xeroxed sheet of paper. “Read this,” he repeated when he handed Jeannie the same thing. “There will be an orientation meeting tomorrow at 3 p.m., and all your questions will be answered then.”

“There’ll be some part-time openings?” Jeannie asked.

“I said all your questions will be answered at that time.” Howard turned to leave.

“Three o’clock,” I said.

He was gone.

“Golly,” Jeannie said as she folded the paper into eighths and jammed it into a pocket. “Now I’ll have to miss some work tomorrow. Don’t you think he could have told us that before making us wait all this time?”

The three o’clock meeting was actually a get-together for working employees and an opportunity for them to meet George Bray, the new director of personnel.

They seemed to like Bray straight off (Jeannie whispered: “Now he’s a nice looking man.”), maybe because he used an appealing country guy/football coach vernacular that made them relax into forgetting he’d just been appointed the nightclub’s Mr. Fixit.

After the meeting, the waitressing applicants (there were six of us now) sat together on the top two rows of bleachers and watched Don Howard talk to some people, then leave without acknowledging us. Where’d he go? He was here a second ago. Do we have jobs?

We found him in the VIP Room. He had another meeting to go to, he said, and he’d be back with us after that.

An hour and a half later, a couple of girls got up to call their husbands to tell them they were running late. We’d exhausted our topics of conversation by then. We’d discussed country music (“I love Willie Nelson,” said one girl. “He looks like a dog but can sing like a dream.”); we’d listened to stories about utility cutoffs (“All my life, we’ve been jacked around, having some utility cutoff or another,” Tammy said.); and we’d exchanged what folklore we’d heard about the club. “If you’ve worked at Billy Bob’s Texas,” one girl said, “you can go off and work in any nightclub in the country.”

“That’s true,” Tammy said. “My parents wanted me to get an office job or something, but I said ’no way, man.’ This is where all the money is.”

“Oh, and watch the floors,” a girl named Connie said.

“That’s right, that’s what I heard,” said Tammy. “A friend of mine who worked here said she found a hundred-dollar bill by the popcorn machine.”

“Can you imagine?” someone said in awe.

Every so often, Jeannie would glance at her watch and say it didn’t seem right to keep us waiting so long.

“I don’t mind,” Tammy said. “I got nuttin’ to do.”

It was well past dark when Don Howard and George Bray came out of the management office. Howard’s hat was pushed up toward the back of his head. Bray’s sport coat was open, and his hands were pocketed in the front of his jeans. Thumbs out.

“Okay now, girls,” Howard said, “You’ve all met George Bray. You’ve filled out applications, right?” We nodded.

“There will be a waitress training session Saturday at one. Okay? So ya’ll need to be there, and then you’ll know whether we can work you in or not.”

“What should we wear?” Tammy asked.

Bray moved a little closer to the table and said, “Come naked.” There was an awkward silence.

“Okay, so thank you all for coming,” Howard said in his best stage voice.

We gathered up our purses and coats.

“And we’ll see you Saturday.”

Outside in the cold, Jeannie pulled the furry hood of her parka up over her head. “You’d think they could have told us that without making us sit there so long.”

“Macho. Macho. Macho,” Connie said.

“I wonder what Don Howard looks like, you know, without his hat,” Tammy said.

“Oh, don’t get me wrong,” Jeannie said. “He’s a nice looking man.”

• • •

Author