The windows of the new Winspear Opera House have a name: the Annette and Harold Simmons Signature Glass Façade. Ascending 60 feet, it was designed to create a seamless flow from the exterior park to the interior lobby. It is ironic that a monument to transparency would be made possible by a $5 million gift from a man like Harold Simmons, who, despite his enormous wealth, has managed to conduct his affairs in relative obscurity.

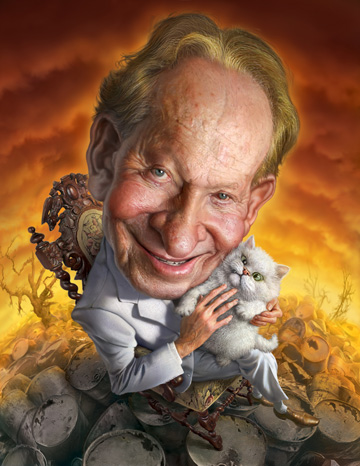

Simmons, 78, rarely grants interviews. He declined to answer questions for this story. The best intel on him comes from two places: an authorized (and thus sanitized) 2003 biography titled Golden Boy: the Harold Simmons Story and a very public, very ugly lawsuit brought against him by two of his daughters in 1997.

Simmons was born in rural Golden, Texas, where he grew up in a shack without plumbing or electricity. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from UT Austin, where he earned a master’s in economics. In 1961, he bought a drugstore across the street from SMU with $5,000 of his own money and a $95,000 loan. Twelve years later, he owned 100 stores that he sold to the Eckerd chain for $50 million.

After that first big payday, Simmons went on to amass a vast fortune by acquiring and selling a variety of companies, including Amalgamated Sugar, Lockheed Corporation, McDermott International, Muse Air, and many others. Simmons is often called a “corporate raider,” though he bristles at the term. In a video produced in 1990 during his effort to take over Lockheed Corporation, he said, “A corporate raider is destructive. That’s not my record at all. I’m a builder.”

Today, through his holding company, Contran Corporation, Simmons controls a thicket of private and public companies. The largest subsidiary is called Valhi. Based in Dallas, the publicly traded Valhi, about 95 percent of which is owned by Contran, conducts operations in metals (Titanium Metals Corporation), chemicals (NL Industries and Kronos Worldwide), waste management (Waste Control Specialists), and precision ball bearing slides and locking systems (CompX International). In 2008, the revenues of the companies under the Contran umbrella eclipsed $4.3 billion. As an officer of many of the companies, Simmons took home about $10 million. Forbes pegs his worth at $3.7 billion. That’s down about $3.2 billion from the previous year, though it still puts him at No. 80 on the magazine’s list of richest Americans.

Simmons has been generous with his wealth. He has given away more than $300 million, including a $20 million endowment at SMU and $50 million to establish a cancer center at UT Southwestern Medical Center. But he has used his money in other ways that have drawn decidedly less favorable press.

His NL Industries has been the subject of continuous litigation. The most recent case involves plaintiffs who managed the company that cleaned up NL Industries’ environmental liabilities. They were also minority shareholders. In 2009, a Dallas County jury found NL Industries liable for not honoring contractual agreements and manipulating stock values. The plaintiffs were awarded $178.7 million in damages.

On a more personal level, before he sold out to Eckerd, Simmons and his second wife put their money in a trust for their daughters (he has four, two of which were born to his first wife). Simmons took the unusual step of naming himself the sole trustee, giving himself broad powers to spend and invest the money as he pleased. His wealth grew in those trusts without much attention until 1991, when the IRS began raising difficult questions. As the New York Times put it: “Why were his homes, his jet, even the jewelry his wife wore, accounted for as corporate purchases or expenses? How could he say that all his holdings formed one huge tax-exempt trust when he treated them as properties he still owned, managed, and enjoyed?”

The Times story arose in 1997, after two of his daughters sued Simmons over the way he was managing their trusts. Simmons had tried to restructure the trusts, a process that forced him to, in effect, file suit against his daughters and their children. His third daughter, Andrea Swanson, had just returned home from the hospital with her first baby, who’d been born three months prematurely. Simmons asked his daughter to drop the court papers into the baby’s crib.

The family squabble brought to light that Simmons had broken campaign donation laws. Swanson told the Times that her father gave her $1,000 for each blank political donation form she signed. Simmons said he gave the money not as a quid pro quo but as a way to show affection. In 1993, he was hit with a $19,800 fine for violating contribution limits. Five years later, he settled the lawsuit brought by his two daughters by paying them each $50 million. He no longer talks to them.

Which brings us back to the engine that has driven Simmons to this point. In his Forbes listing, after mentioning how much money he lost in the last year, it says this: “Planning to make it back with Valhi’s recently approved low-level radioactive waste disposal license.”

Exploring the implications of that one sentence will reveal Harold Simmons’ real genius. In short, it appears that the “King of Superfund Sites,” as he’s known in some circles, has figured out a way to clean up a radioactive mess one of his companies made in Ohio by—according to some experts—creating another radioactive mess in West Texas. The best part: he’s gotten the folks in West Texas to support the plan and the federal government to pay for it.

===Simmons has been generous with his wealth. He has given away more than $300 million, including a $20 million endowment at SMU and $50 million to establish a cancer center at UT Southwestern Medical Center. But he has used his money in other ways that have drawn decidedly less favorable press.!==

Cadillac Heights is a small enclave south of downtown Dallas, situated close to the Trinity River. About 200 small frame houses, most built in the 1940s, are hemmed in on three sides by various metal industries, a meat rendering plant, and a water treatment facility. Pit bulls roam freely on crowned narrow streets that are thinly paved. From street to yard, there are dirt ravines and no concrete curbs and few walkable sidewalks. The neighborhood floods frequently, evidenced by water lines on the bases of homes and debris clinging to fences.

For years, two lead smelters operated in Cadillac Heights, poisoning the people who lived there. One, Dixie Metals, remained in operation until 1990. It’s now a mounded landfill with a chain-link perimeter fence in the middle of a residential area. The other smelter closed in 1978, but remnants of it remain standing. It belonged to a company now controlled by Harold Simmons, NL Industries.

Peter Johnson, longtime community activist, remembers Cadillac Heights’ recent past: “It was a community that was poisoned; the earth had been polluted. And it stunk. Most of those people were sick with cancer and kidney problems. The children had birth defects. They were poor people. The city didn’t pay attention to their problems. Lead was a part of that community for a long time.”

In smelters of the recent past, lead was reclaimed mostly from used vehicle batteries. The lead was melted down in furnaces to arrive at reusable product. The process also produced metallic refuse called slag. The slag and casing debris from the batteries would often be dumped in landfills both on- and off-site. It was also mixed with soil and used for ground cover in areas close to the smelter. In Cadillac Heights, casing debris was used as pavement for driveways.

In February 1997, the state of Texas announced it would fund a cleanup of Cadillac Heights with the possibility of suing NL Industries and Dixie Metals to recover costs. The state entered into negotiations with the companies, and by April, both had agreed to pay for the removal and replacement of lead-contaminated soil from the yards of 57 houses.

But of the neighborhood’s 230 properties, 62 tested for high levels of contamination. The state spent $180,000 to clean up the five properties that the companies claimed did not warrant their attention. The cleanup did not include particulate matter inside homes or contaminated soil in common areas such as alleys and ditches. And what lead remained in Cadillac Heights has no doubt been dispersed by the periodic flooding to which the neighborhood is subjected.

In Lopez, et al. v. The City of Dallas, counsel for the plaintiffs provided ample evidence that the city had continued a policy of discrimination by failing to provide flood protection to Cadillac Heights residents. Despite the significance of the U.S. District Court’s ruling in 2006, the construction of a levee has yet to materialize. According to a city spokesperson, “If funds become available, construction will start in 2012.” The city of Dallas presently buys houses piecemeal from the remaining Cadillac Heights residents, the money coming from the 2006 bond election. Once Cadillac Heights is cleared of people and houses, the property will become home to the Dallas Police Academy.

Community activist Luis Sepulveda knows about lead contamination. He was a driving force in getting the EPA to designate part of West Dallas a Superfund cleanup site. To his mind, the prospect of rebuilding in Cadillac Heights causes concern for future occupants. “I’m not sure they’re [Police Academy] aware of what property that is being bought,” he says. “There is so much buried there. It will contaminate the water eventually. What if they [the officers in training] get sick? What if they have respiratory problems?”