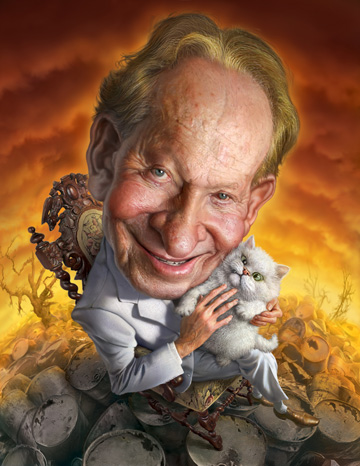

Why would Harold Simmons become involved with an operation like NL Industries? He bought the company in 1986, long after the dangers of lead were known and the lawsuits had begun working their way through the court system. The answer, it seems, is that Simmons doesn’t mind a mess if there’s money to be made.

NL Industries’ history is lengthy and layered. In more than a century of continuous business, NL Industries’ operations have involved magnesium, titanium, and zinc; lead pigment and lead-based paint; lead smelters; lubricants and drilling equipment for oil fields; municipal and industrial waste disposal; the enrichment of uranium for nuclear weapons; and the production of projectile weapons using depleted uranium.

NL Industries sloughed off lead operations in 1974, a prescient move that predated the federal ban on lead-containing paint by four years. As litigation against the lead industry largely failed in the recovery of compensation, and titanium dioxide began replacing lead as a paint enhancer, NL Industries landed on its feet. Its subsidiary, Kronos, is currently one of the largest manufacturers of titanium dioxide pigments in the world.

But NL Industries has left a legacy of contaminated sites across the country. According to the company’s annual report from 1994, NL Industries and its subsidiaries, which included Kronos, had “been named as a defendant, potentially responsible party, or both … in approximately 80 governmental and private actions,” with many sites and facilities on the EPA’s Superfund National Priorities List or similar state lists.

While NL Industries’ operations in Cadillac Heights were never designated as a Superfund, another of its operations in Ohio was.

===Then one day she got a call from her congressman. He said that three off-site wells had been contaminated, but the Department of Energy was telling everyone they were fine and below dangerous limits.!==

In early 1985, Lisa Crawford, a full-time working mother, lived directly across the street from an NL Industries operation in Fernald, Ohio, a rural area 15 miles to the northwest of Cincinnati. When she and her husband and 2-year-old son moved into the house six years earlier, they were looking for a quiet country community “away from the blacktop and cement,” as she puts it. The checkered water towers and signage at the facility had given her few reasons to question its operations. A large sign at the entrance of the 1,050-acre site featured an image of a little Dutch boy next to the words “National Lead of Ohio.” Dutch Boy paint was a product line of NL Industries.

Then one day she got a call from her congressman. He said that three off-site wells had been contaminated, but the Department of Energy was telling everyone they were fine and below dangerous limits. A year earlier, in 1984, an accidental uranium release from the NL Industries facility had received media attention. The accident, along with the call from the congressman, led the Crawfords and other residents to worry about the facility they knew relatively little about.

Beginning in 1951, NL Industries contracted with the Atomic Energy Commission (then its successor, the DOE) to produce high-purity uranium. The facility made uranium products that were fed to other facilities within the nuclear weapons complex.

NL Industries performed similar work in New York. The facility in Colonie operated as a munitions plant beginning in 1958. In 1984, the New York State Supreme Court closed the facility because of excessive airborne releases of radioactive material. Cleaning up the site took two decades and cost $190 million.

In Fernald, Ohio, the story unfolded in a similar fashion. In 1985, after the accidental uranium release and the contaminated wells, NL Industries’ contract to operate the facility was canceled, and the facility was thrust into a struggle between the EPA and DOE over which agency had authority over operations. The EPA wanted an immediate cleanup of the site; the DOE, however, wanted the facility to remain operational. In 1986, the year Harold Simmons bought NL Industries, a congressional amendment to law required DOE to remediate the Fernald site under a Federal Facilities Compliance Agreement with the EPA. Cleanup didn’t start until 1991, and remediation wasn’t declared complete until 2006—at a total cost of $4.4 billion dollars.

NL Industries’ facilities at both Fernald and Colonie were provided substantial protection by having contracted with the DOE. In 1989, the DOE agreed to pay $78 million to settle claims with the residents who lived near the Fernald facility; the jury had recommended $136 million. The settlement is viewed as significant on two counts: first, it was an admission by the government that a weapons production facility may have harmed nearby residents. Second, the suit had been brought against the contractor, but the government paid, absolving NL Industries of liability.

Crawford, one of the plaintiffs in the case, had initiated contact with the Ohio EPA and Ohio Department of Health soon after the phone call from her congressman. Both agencies provided testing but gave her conflicting advice about whether she should drink from her well. Crawford immediately knew what to do.

“We stopped drinking the water then and there,” she says. But her worries went beyond what she drank. “Every time you have to put your child in a bathtub full of water, you wonder,” she says. “And every time you wash a load of clothes, you wonder. And every time you do a load of dishes in the kitchen sink, you wonder.”

Further testing at Fernald would prove that wells in proximity to the NL Industries facility were not the only water sources in Ohio subject to uranium contamination. In 2008, the DOE settled a lawsuit with the Ohio EPA for $13.75 million for radioactive contamination of groundwater, including the Great Miami Buried Valley Aquifer. Ohio officials estimate that radioactive contamination of the groundwater may persist for 100 years.

Fernald, Cadillac Heights, Colonie—NL Industries has, over the years, created quite a mess. As noted, much of that mess was made before Harold Simmons bought the company. But he clearly learned from its history.

In 1995, he bought a company called Waste Control Specialists (WCS), a hazardous waste disposal company. It is now on the lucrative end of Superfund cleanups. In 2009, for instance, WCS buried 390,000 tons of sediment contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, dredged from the Hudson River in Upstate New York. The waste is a result of General Electric Company’s 30-year discharge of PCBs into the water system.

Also last year, WCS buried 3,776 canisters of uranium byproduct waste generated by the NL Industries facility across the street from Lisa Crawford’s house in Fernald, Ohio.

One Simmons company made the waste. The other buries it. And it all comes to West Texas.

===Ohio officials estimate that radioactive contamination of the groundwater may persist for 100 years.!==

Andrews County, in West Texas, is mostly flat and thoroughly punctured with oil and gas wells. For many people, the land offers a hardscrabble life broken into two rotating shifts, crews of six to eight men in F-350 duallys headed out to oil fields or coming back from them. They drive fast, as if by echolocation. Between shifts, the roughnecks spend their time in the cafes of the city of Andrews and at impromptu barbecues and card games held on sidewalks, outside doorways of dusty motels.

Waste Control Specialists is located 31 miles west of Andrews, on the Texas-New Mexico border. The facility sits on a 1,338-acre site, where it is licensed to service a wide variety of projects, from toxic and hazardous waste resulting from Superfund sites to various classes of radioactive waste from DOE cleanups.

How Simmons was able to obtain licenses from the state of Texas to dispose of nearly the full gamut of radioactive waste is more a story of politics and money than one of sound science. Critics have pointed out that the nation’s largest aquifer underlies the site and is in an earthquake hazard zone. As Simmons told the Dallas Business Journal in a rare interview in 2006: “It took us six years to get legislation on this passed in Austin, but now we’ve got it all passed. We first had to change the law to where a private company can own a license [to handle radioactive waste], and we did that. Then we got another law passed that said they can only issue one license. Of course, we were the only ones that applied.”

Legislative changes and licensing have been one half of the equation. The other half has been the company’s successful assimilation into the region with little skepticism from residents and local media. Andrews County has one major population center of approximately 10,000 residents, the city of Andrews, and no interstate. WCS promises 60 permanent positions after the construction phase and a facility whose “operating costs will boost the region’s economic activity by about $75 million a year.”

Reports in local media have misled residents about the nature of the waste being disposed of. In October 2009, WCS sponsored a tour of its facilities exclusively for local media outlets. At the time, the disposal of the canisters from Fernald was almost complete. Reports of the tour described the canisters from the Fernald site as a product of the WWII war effort. The Odessa American reported that the waste is a “byproduct from ore … used in the Manhattan Project during World War II.” And the Fort Stockton Pioneer said, “According to WCS, the Fernald Project is the disposal of 3,776 canisters—20,000 pounds each—containing uranium production waste from the World War II Manhattan Project.”