In Japan, there are many quiet masters. In sushi as in sword-making, there are the shokunin, highly skilled artisans recognized as national treasures, living legends. Japan’s is a culture of patient perfecting, and this honing trickles down to each aspect of a dazzling food culture, with its simple harmony of elements that are not simple at all.

In Dallas, too, we have hidden masters, discreetly and obsessively plying their craft. We have Teiichi Sakurai, who was the first to usher in something truly remarkable with Teppo and now Tei-An, his refined soba shop. And others, who have opened places where all the sensory pleasures of Japanese cuisine play out, whether at a late-night izakaya, the stand-up counter of a ramen shop, or a sleek, cool sushi bar.

While it may seem unlikely, Dallas is a destination for Japanese food, with decades-old depth and a whole new generation of Japanese spots opening up. And so we offer a guide to the intense and fully immersive pleasures of Japanese food in Dallas. Enter hidden worlds. Learn about the hidden places. Because although Dallas is no Tokyo, in certain rooms it almost could be.

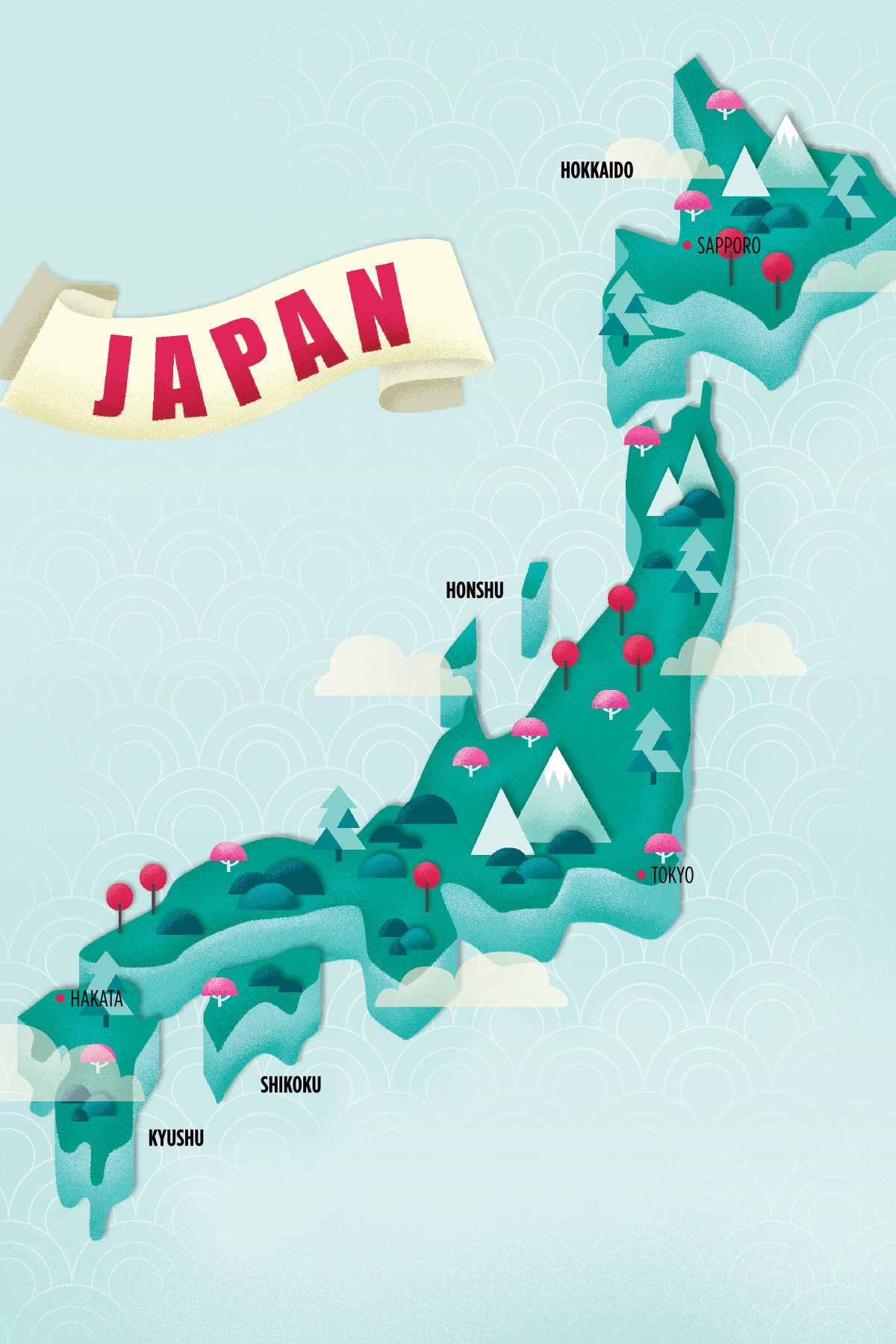

The Geography of Japan

The Japanese archipelago, an arc in the Pacific Ocean, stretches in latitude from a distance that would encompass Montreal to Miami, from Hokkaido’s snowcapped mountains to Okinawa’s almost tropical climes. To take advantage of regional delicacies, the Japanese eat with the seasons, whether grilled freshwater eel or a perfect white Okayama peach. The ultimate expression of this seasonality is kaiseki, the Japanese form of haute cuisine, in which each course in an exquisitely codified multi-course meal. It draws inspiration from seasonal ingredients, mixings mountains and sea, and moving through various cooking techniques.

For a taste of the seasons, nothing beats fresh spring bamboo shoots, which I’ve found, for example, at Tei Tei Robata. And more and more restaurants are offering seasonal fish imported daily. Japan’s string of islands represent various climates and pockets of cuisine. Look carefully, and you can find them all in Dallas. (Well, maybe not the puffer fish.)

Hokkaido

rnJapan’s northern-most island is known for the seafood fished from its cold waters. Sea urchin rice bowls are a taste of Hokkaido, as are fishermen’s dishes like the salmon-stocked seafood hotpot ishikari nabe. Salt ramen (shio) is a specialty from the city of Hakodate, while Sapporo has its own hallmark.

Sapporo

rnMiso ramen, creamy and nutty-sweet, has its origins here, where it’s served with two other Hokkaido staples: corn and sweet butter.

Honshu

rnJapan’s main island has a variety of specialties: Kyoto’s warming hot pots and vegetarian delicacies from the Buddhist monk tradition of temple food (think simple tofu and kelp broths); Osaka’s octopus dumplings, takoyaki; Hiroshima’s savory cabbage-freighted pancake, okonomiyaki; Kobe’s exquisitely marbeled Wagyu.

Tokyo

rnThe current capital saw the birth of the soba house and specialties like sushi and tempura, which flourished during the Edo period (1603-1868).

Shikoku

rnThe smallest of Japan’s four main islands is known for the chewy, chubby, delightful wheat noodle known as udon.

Kyushu

rnThis southern island is the birthplace of the distilled spirit shochu (made from sweet potato, barley, buckwheat, rice, or potato); Nagasaki’s champon (pork, noodles, and vegetables in broth); and all manner of porky goodness involving the famed Kurobuta (Berkshire) pork, prized for its sweetness.

Hakata

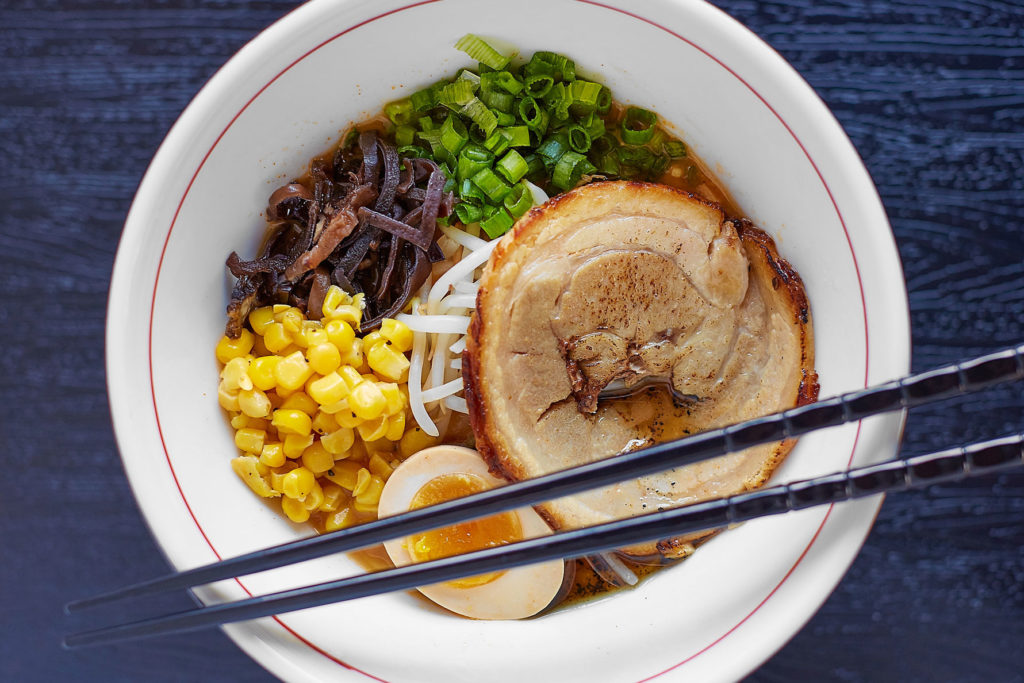

rnThis city on Kyushu is the birthplace of the iconic and intensely porky tonkotsu ramen, its broth milky from long-simmered bones, its top crowned with slices of chasu, pork belly.

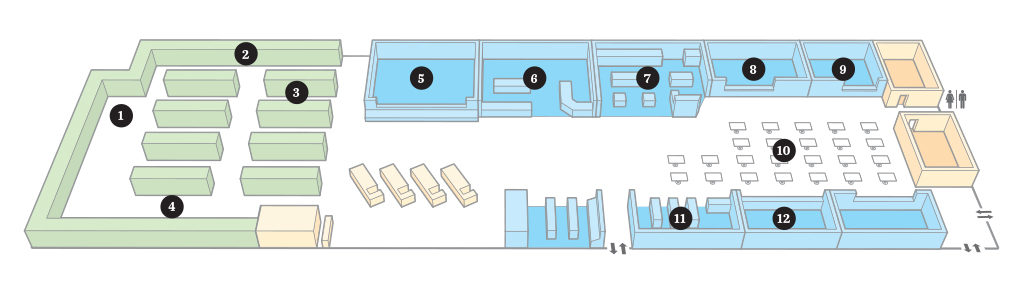

Izakaya

Think of an izakaya as a pub, a cozy yet boisterous place for small bites to accompany drinks. You can throw back a few rings of grilled squid or nibble on a chicken-heart skewer and then wash it down with a frosty Asahi Super Dry or a light and fruity chūhai (a shōchū highball). It’s all about communal comfort food, set out on little plates to encourage snacking. You’ll find belly-filling dishes, such as bowls of lip-smacking ramen with thick slicks of black garlic oil on the surface, or humble student fare like omurice (a Western-style omelet filled with fried rice) and wafu pasta (spaghetti reddened with ketchup and tossed with ham).

So enter. Check the board for handwritten specials. Find a table with your friends. And then settle in for a lively night organized around shared adventures.

Yama Sushi

The door cheerfully jingles open at this funky joint at the end of a strip mall, which stays open till 2 am most nights. Come with a crowd for grilled squid or the kitchen’s excellent version of the thick, savory pancake called okonomiyaki, fluttering with bonito flakes. Under neon signs advertising highballs made with barley or sweet potato shōchū, patrons quaff pitchers of Asahi.

Mr. Max

Slip off your shoes, sit cross-legged at a low table, and choose your sake cup from the basket proffered. Mr. Max is about full immersion. Hand-lettered signs may help steer you toward oden (fishcakes in dashi broth), grilled fish collars, miso-braised eggplant, or beads of raw octopus riled with wasabi. Here you’ll find some of the best takoyaki (fried balls made of octopus) in town.

Hanasho Japanese Restaurant

There’s no particular charm to make you want to linger, but don’t underestimate this three-decades-old spot. The most intriguing items are in an old-school vein: chawanmushi, a savory egg custard filled with tender chicken and tiny shrimp; grated Japanese yam, faintly sweet and starchy, mixed with raw tuna and nori strips; and green tea noodles.

Ino Japanese Bistro

This isn’t technically an izakaya, but it’s a homey spot imbued with the presence of its owners. Lunch starts with lightly pickled napa cabbage and a miso-dressed salad, and might lead to one of their elegant bento boxes ($28 at lunch; $40 at dinner). The tonkatsu curry is a perfectly breaded and fried cutlet under a tawny-colored curry, full of root vegetables.

Grill Masters

The tradition of Japanese-style grilling is centuries old, dating back to northern fishermen in Hokkaido who carried wooden boxes of red-hot charcoal on their boats so they could cook their catch when they landed on the beach at the end of the day. The grilling method is called robatayaki (robata for short), meaning “around the fireplace.” Food is cooked over a hibachi using binchōtan, a special kind of charcoal made from white oak, which burns white-hot with little or no smoke or flames.

Teppo

Teppo best embodies the tradition of yakitori, the expert grilling of all parts of the chicken, including the heart, gizzard, and skin. Skewers of chicken thigh, perfect with the bright pungent touch of Tokyo negi (green onion), lie side by side with shiitake mushroom caps, beef heart marinated in miso and seared to caramelization, and juicy chicken meatballs that you dredge through a quail egg wash for extra luxury.

Tei Tei Robata Bar

At this chic modern restaurant, there are artichokes with wasabi aioli and palm-long smelt, tender bellied but crispy on the outside. Sea bass bundled into a foil packet on the grill releases a luxurious, intoxicating aroma from enoki mushrooms and a buttery miso sauce. In the spring, they might have tender bamboo shoots, light and vegetal in flavor, or ankimo, a monkfish liver slab with slightly wild shiso leaf.

Ken Japanese Bistro

Time stops in this humble spot, where you are on the grill’s lazy time. From the bar, you can watch the patient turning of skewers. When your juicy bits arrive, you’ll get your own charcoal grill to keep them warm. The classic chicken thigh and negi is marvelous. Beef tongue is tender umami richness; shishito peppers can be dabbed with miso or tōgarashi spice.

Sushi Robata

Sake-marinated black cod has the hallmarks of the high-heat robata: soft and tender inside, the skin crisped from the grill. Appetizers include innovations like a silky scallop custard set with gelatin in a scooped orange. And here you’ll find what is perhaps the best nabeyaki udon in town, the chubby noodles (fat and slippery, a delight to slurp) in a broth flavored with shiitakes and kombu kelp.

Japanese BBQ

Japanese barbecue, yakiniku (yaki = grill; niku = meat) refers to a tradition of grilled meats.

It’s stylistically similar to Korean barbecue, but has become its own domain of expertise, exercised over the telltale hot grill set into the table, highlighting simple cuts of high quality beef rather than pork.

This is where you do a deep dive into Japanese Wagyu, beef known for its lustrous marbling, its pinnacle the A5 designation and its golden chalice the beef from Kobe. Where Korean barbecue includes swaths of pork, in Japanese barbecue, the focus is on beef: the precision of the cuts, the quality of the meat. Shishitos or other vegetables get snuggled alongside meats on the grill (rather than coming in Korean barbecue’s parade of saucers of banchan: pickled daikon, kimchi, and other gojuchang-laced treats). And this is not about galbi, which are cuts mopped in saucy marinades that bring garlic and soy and the sweetness of apples or pears into savory play.

In Japanese barbecue, meats are generally not marinated, but have a tare: a seasoning for accenting the cuts after grilling—most often the common soy, sake, mirin sugar, garlic, sesame mix, but also garlic-shallot or miso-based. The cuts themselves might be beef belly, rib eye, New York steak, sirloin flap. They might include offal—tongue with salt and lemon juice is delicious—chicken breast and thigh, or seafood. Look for off-menu Wagyu cuts. Gather your courage. Take to the embers. It’s all in your hands. Pray you don’t desecrate the Wagyu, that sine qua none of premium beef.

Eat it at Niwa Japanese Barbecue in Deep Ellum.

Ramen

When it comes to ramen, there is no single bowl to rule them all. The Tokyo (shoyu) style, with curly noodles in a clear broth darkened with soy sauce, remains dominant, embraced by the hordes of businessmen who first descended on stand-up-only ramen shops that proliferated in Tokyo in the booming ’70s. But there exist as many ramen styles as there are regions in Japan, some born in the north, some in the south.

When it comes to ramen, there is no single bowl to rule them all. The Tokyo (shoyu) style, with curly noodles in a clear broth darkened with soy sauce, remains dominant, embraced by the hordes of businessmen who first descended on stand-up-only ramen shops that proliferated in Tokyo in the booming ’70s. But there exist as many ramen styles as there are regions in Japan, some born in the north, some in the south.

In addition to shoyu, the four greats include shio, miso, and tonkotsu. Shio, meaning “salt,” is the light style from the northern island of Hokkaido (particularly Hakodate), and often has an oceany aroma with wakame seaweed. Mild, creamy miso ramen from Sapporo (Hokkaido) is traditionally served with a pat of butter and corn, the island’s sweet crop. And the southern island of Kyushu produces the iconic tonkotsu (originally hailing from Hakata), an object of obsession that’s intensely porcine, milky, and almost funky from the marrow of long-simmered pork bones. All are based on chewy alkaline noodles, whether the springy, curly yellow Sapporo style or thin, straight white Hakata style.

More Places to Noodle Around

Ramen Hakata

They may specialize in tonkotsu, but also try their clear, bright yuzu shio ramen.

Tanoshii Ramen + Bar

A trendy place for adventurous bowls such as lemongrass chicken and dumplings or crab and truffle butter.

Wabi House

Try creative izakaya bites and their brothless tsukemen ramen with pork belly dipping sauce.

Hokkaido Ramen Santouka

The miso ramen at this food court stall in Mitsuwa Marketplace (see the section below) is light but full-bodied, with a subtle, creamy sweetness and light ginger glow.

Sushi

It is a singular pleasure to sit at a sushi counter and watch the chefs expertly cut and drape fish over seasoned rice or beautifully fan sashimi over a mound of ice. The rapport you establish over an evening, especially if you have chosen to be paced through an omakase (chef’s choice tasting), is like no other—part awe, part admiration. Take advantage. Beyond entry-level maki roll standards, excellent sourcing from Tokyo’s Tsukiji Market and our sushi masters’ skills allow us to try kombu-cured flounder with salted umeboshi plum; perfectly scored shad with a hint of ginger; supple, silky flying fish sashimi; creamy kanpachi (Japanese amberjack); and aji (horse mackerel) with its silvery sheen.

Sushi Sake

Many come for the drama of a well-made dynamite roll, rainbow roll, or scallop volcano engulfed in creamy mayo from Takashi Soda, the owner and longtime sushi chef. But this is also a place to make discoveries among the daily specials: pen shell tairagai, tsubu gai whelks, or chewy surf clams. And don’t miss Soda’s take on tamago, the folded omelet seasoned with sake, mirin, and a touch of sugar. A beautiful green band of seaweed powder is his special touch.

Uchi

Some of the most dazzling sushi in Dallas can be found at Uchi. Each fish comes with its own accompaniment (yakumi) as perfect punctuation. Seafood is flown in from Tokyo’s Tsukiji Market daily. Hot and cool tastings are visually arresting, perhaps house-made pickled plum and lardo or scallop paired with huckleberry and purple and white nasturtium blossoms. End with seared foie gras nigiri served with a decadent fish sauce caramel.

Yutaka

In this marvel of a small space in Uptown, the talented Yutaka Yamato approaches his craft with adroitness and solemnity. The foundation is basic: impeccable fish over perfectly seasoned warm sushi rice. But this is one of my favorite places for omakase. Yamato pushes the envelope, and the precision of flavors leads you to new places. In one creation, invigorating as an ocean plunge, crisp, clean snapper wraps bright orange uni, complementing its saline pungency.

Nobu

In Nobuyuki Matsuhisa’s Peruvian-Japanese empire, all is jazzy, sleek, and moody among the stands of birch trees. Order the exquisite Kobe Wagyu beef, which comes in seven styles with price tags that will make you dizzy. The spectacular tataki’s finely marbled beef melts on the tongue like sashimi. At the sushi bar, edible gold leaf dots the king crab roll.

Masami Japanese Sushi & Cuisine

The sushi bar over which “Ryo” Hideyuki Iwase presides is the warm heart of Masami. Iwase’s wife, Yuko, has made many of the textile elements that give the place its cozy charm: indigo dyed cushions at the low tables; the aprons the servers wear; and the sushi chef’s uniforms. Here, the style is personal and interactive. When you order horse mackerel (aji) sashimi, the tiny skeleton will be whisked to the kitchen and then presented to you again deep-fried, a delicacy you crunch tip to tail. Intense marinated baby squid is not for everyone, and certainly not for the faint of heart, but you’ll find some of the best tako wasabi in town, made with fresh octopus.

Mr. Sushi

Huge orders may come out in Viking boats, but the quality of the fish is indisputable. San Diego uni comes with a raw quail egg yolk tucked into the collar of nori, lending a regal richness. You can get freshwater eel, not sauced but simply broiled with salt, a marvel so buttery it seems a sin. Once you know the secret, you can’t help but return. The chefs are thoughtful about sequencing if you order omakase. And the welcome is far warmer than its strip mall location would suggest.

Tei-An

Everyone seems to remember the first meal they ate at Tei-An, where flavors are as elemental as earth and woods and sea. Perhaps they had cold soba noodles served on a dark wicker tray with dipping sauces. Hot soba with duck breast, or cool soba with plum and daikon. But at Teiichi Sakurai’s elegant soba shop, noodles aren’t the only treasure. Fish comes in several times weekly and finds its way into breathtaking sushi and sashimi. A four-part sea urchin tasting has you discover its stunning saline intensity as if for the first time. Excellent chawanmushi involves shiitake mushrooms and succulent crab settled in a light egg custard. Flavors are quiet and subtle. Even in the soba ice cream with runny Japanese black honey.

Omakase

Omakase appeals to the fearless, to those who desire a particular kind of immersion. When you request omakase (a chef’s choice tasting), you put yourself in the sushi chef’s hands, entrusting yourself to this craftsman’s vision, which will intersect with yours—quietly, thrillingly—for an hour. Sitting at the sushi bar, you willingly relinquish choice to experience what is often a finely orchestrated symphony. If you’re open and adventurous, it’s the best way, a la carte abandoned for a taste of today’s best ingredients and the chef’s care, his talent on display. Often, it is a very good deal.

The best omakase chefs watch you. They pace themselves based on your pace, attend to your expressed preferences. They may ask you initial questions, size you up: How hungry do you seem? Do you prefer lighter fare, oily or fair-fleshed fish? How welcoming are you of the novel? And then begins the symphony. They hand you with a gentle or formal gesture, over the counter, the elements in a well-paced parade. (Unless you’ve specifically ordered sushi omakase, they will likely lead you through several cooking techniques: grilled, simmered, fried.) If you arrived keen on toro, say so. A good omakase chef will loop your interests into his scheme. Ultimately, an omakase experience feels balanced, and never too much.

It ends with a bill bearing a non-itemized price. Run the items in review in your mind. Or don’t. Let the sensory impression wash over you. This is part of abandoning yourself to the chef’s choice, the symphony that night.

Note: Some restaurants have a fixed omakase price (often $100 and upwards). At others, you set your price and the rest follows.

Upscale tradition: Yutaka Sushi Bistro

Yutaka Yamamoto sends you through cool and warm tastings at his solid ash bar. Sashimi comes over ghostly daikon in a hollow sea urchin shell. Nigiri is flawless over perfectly seasoned rice. Inventive warm bites, like braised chard with miso, enchant. The sequence ends with a final hand roll, miso soup, and a light matcha tea sends you out into the night. I never fail to emerge a little dazzled, as from a cabinet of wonders.

Top-tier modern: Uchi, Nobu

At Nobu, inventive modern-Japanese means pale, chic soy rice paper rolls, torched yuba (tofu skin) with caviar, and truly excellent sourcing. At Uchi, it means include machi cure, the addictive Uchi staple that pairs smoked yellowtail with Marcona almonds and yucca chips. Your omakase might include side by side comparisons: the golden jewel dots of flying fish roe vs. the translucent sunset-colored pearls of salmon roe. Each bite is distinct thanks to their work with yakumi (accents): boquerones with olive oil, baby bonito with garlic oil, or firm flounder fin muscle accented with smoked salt. And it will end with one of their whimsical desserts.

Cozy, affordable excellence: Masami

Hand-lettered specials complement the distinct hospitality of a place centered around one person, Hideyuki “Ryo” Iwase, who may or may not be your omakase chef, but whose personality shines either way. Masami offers a vastly authentic omakase, and you can set your price. You will start with small appetizers: maybe marinated baby squid (saline and funky) or tako wasabi pungent with fresh-grated wasabi root. Next, sashimi: gossamer aji; salmon, fat ribbons in pale orange flesh; seared tuna tataki, the light sear intensifying the meaty, oceanic flavor. Next, sushi: pearly Japanese amberjack; crunchy giant clam; yellowtail, sweet prawn, tamago, eggy like a good custard. After which, you get fried carcasses returned to you: the fileted aji and the prawn, the meatier part of the head a crispy-crunchy finale that is extraordinarily delicious. Then perhaps sakura mochi, pretty pink with red bean paste wrapped in a cherry blossom leaf, and always a halved orange, which you eat with a toothpick.

Sake

Chris Melton, who oversees the sake menu for the uchi restaurants, will tell you about an izakaya in Japan that serves sake at 15 different temperatures over the course of a meal—from ice-cold to warm and back again in the summer, when the weather is sweltering; the reverse in winter, before patrons return to icy streets. Melton is determined to help unlock such secrets of a centuries-old Japanese art for a Texas audience, to demystify this spirit made like beer but with the nuances of wine. He wants you to understand its myriad forms: a cloudy nigori, milky and sweet. Hot sake, sipped alongside tempura. A limpid daiginjō, like air and water, perched on the lip of a cedar box.

Chris Melton, who oversees the sake menu for the uchi restaurants, will tell you about an izakaya in Japan that serves sake at 15 different temperatures over the course of a meal—from ice-cold to warm and back again in the summer, when the weather is sweltering; the reverse in winter, before patrons return to icy streets. Melton is determined to help unlock such secrets of a centuries-old Japanese art for a Texas audience, to demystify this spirit made like beer but with the nuances of wine. He wants you to understand its myriad forms: a cloudy nigori, milky and sweet. Hot sake, sipped alongside tempura. A limpid daiginjō, like air and water, perched on the lip of a cedar box.

A 4-ounce pour of sake is full of poetry. Take those made with snowmelt from the northernmost island of Hokkaido, with its volcanoes and natural hot springs. The hard water, laden with minerals, undergoes vigorous fermentations to produce a light, dry, and delicate style. At the other extreme of the archipelago, the southern island of Kyushu has softer water. Kyushu’s sakes tend to be more forceful, sweeter and fuller bodied, with a natural viscosity.

In addition to the source of water, rice is also part of sake’s “terroir.” Native cultivars have been bred for centuries and contain particular ratios of starch, proteins, and enzymes. And while rice moves more freely between prefectures now, some brewers still choose to work with the crops from their area, imbuing each sake with a direct sense of place.

Then comes what Melton calls “the hand of man.” “There is a history of sake-making that was never recorded,” he says. “Every sake-maker makes it differently. Every brewery has its own method.” Adjustments are made in steaming temperatures, pasteurizing methods, and “polishing,” the slow grinding of the rice to strip fats and proteins down to the starch that forms the opaque center of the rice grain. The amount of polishing determines the sake’s grade. To polish to 70 percent of weight can take 24 hours; to get to 50 percent can take almost a week.

“The price of sake is pretty fair,” Melton says, noting that the greater the polishing, the more expensive the sake, since the loss of grain is akin to the loss of whiskey’s “angel’s share.”

But Melton willingly admits that a less polished grain may tell more of a story, its particular fingerprint more present. A slight bitterness or umami characteristic of a junmai might disappear in the higher grades. Why, then, go for a daiginjō, considered a drink for special occasions in Japan?

“Those brewers have mastered the skill of sake,” he says. “It is the pinnacle. You have this ethereal quality, this pristine finish. The bitterness disappears, so it has a delicate, lively mouthfeel. It’s almost a spiritual experience, the way it lives on your palate. These can be very subtle, very soft, but can really hit you.”

Soba

At his upscale soba house Tei-An in the Arts District, Teiichi Sakurai specializes in dishes made with the delicate, fragile noodle he trained in Tokyo to make. The ratio of 80 percent buckwheat to 20 percent wheat flour yields the perfect strands he rolls and cuts. The process takes years to master. Neither as thick as udon nor as springy as ramen, soba has been a marker of refinement since Japan’s Edo period, the years spanning 1603 to 1868, when the city that would become Tokyo made soba houses, tempura, sushi, and tea ceremony popular.

Take advantage. We have a rare treasure in this Zen-like gem. Start your soba adventures and feel free to pair (liberally) with sake.

Dipping soba: For the most traditional take, Sakurai’s cold noodles come on a lacquered wicker tray (zaru). The fine, slippery strands swirl in a sampler of dipping sauces: walnut, then pecan, then black sesame. The nuttiness is magical with buckwheat’s natural earthy flavor, benefitting from these simple preparations which are based on pulverized nuts. At the end, the server will come with a black teapot steaming with soba cooking broth (as tradition would have it), and instruct you to fill the cups that hold the remainder of the sauces and sip. It’s a meditative hiatus before you return to the busy world.

Cold soba: Plum daikon soba comes with salted plum and sulphury daikon. Order the soba with soy sauce, light and smoky.

Hot soba: Duck breast and green onion is one of the most traditional hot sobas. The duck breast is lean and savory, the broth limpid and clear.

Other soba: Short green soba (tinted with matcha powder) comes with curry sauce or sansai, Japanese mountain vegetable. Other inventions belong in the same vein as the restaurant’s Gorgonzola purple potato gnocchi, or truffle-enhanced crab, and squid ink risotto served in a hollow crab shell. At lunch, be like the lunchtime businessmen. Try the short green soba Bolognese with Wagyu beef.

Dessert

After the sushi, after the foil-wrapped enoki mushroom packet has long been removed from the robata grill, and after you devour the nabeyaki udon, dessert may seem like an afterthought. Three of our Japanese pillars in Dallas skirt generic green tea mocha and cheesecake dishes. Instead, they blend impeccable European technique with the nuance of Japanese flavors for desserts that leave lasting impressions and give you reason to end with a sweet course.

Do not miss them.

Tei An stays close to its identity as a soba house with its soba ice cream, which I love for its light buckwheat flavor. A sprinkle of toasted soy powder is a nutty, savory component that tamps down the sweetness of the black honey, whose dark intensity comes from combining Japanese sugar cane syrup and local honey. Tiramisu is incredibly rich, with notes of black pepper and Earl-Grey soaked biscuits. With just a drizzle of black honey, it’s amazing: butter and honey and tea—a stunning departure from the coffee and mascarpone classic. And black sesame mousse—a whip-light texture with pronounced black sesame flavor that you can see atop this section—comes with a tiny dollop of whipped cream and delicate butter cookie.

Teppo’s mix of European technique and Japanese flavors leads to brown sugar panna cotta, matcha sticky toffee cake, soybean flavored chiffon cake with tofu mousse (subtle and good), or crème brulee with carrot pureed into the silky custard. The bruleed top brings out the natural sweetness of the roasted root vegetable.

Tei Tei Robata’s sake ice cream is the elegant essence of custard and essence of sake, a pale composition on a plate with grapes and kiwi.

At Mitsuwa Marketplace, Buy Your Own

Mitsuwa, a large supermarket chain in Japan, chose Plano as the location for one of its newest stores in the United States, one of only four outside of California. This wonderland of all things Japanese can be overwhelming for first-timers. Here’s an aisle-by-aisle guide.

Mitsuwa, a large supermarket chain in Japan, chose Plano as the location for one of its newest stores in the United States, one of only four outside of California. This wonderland of all things Japanese can be overwhelming for first-timers. Here’s an aisle-by-aisle guide.