To stay relevant, 73-year-old German filmmaker Werner Herzog recently told the Los Angeles Times, “you’d better have a new film out every half-year.”

Even by those standards, however, Herzog is far exceeding his own expectations. In June, Herzog’s latest feature film, Salt and Fire, a romantic thriller set against the backdrop of an ecological disaster, hit theaters. It followed closely on the heels of Herzog’s latest documentary, Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World, which applies Herzog’s particular documentary style—wandering ruminations; a penchant for finding the surreal in reality; his distinctive, thick Bavarian accent as narrator—to the subject of the internet. Another feature Herzog finished last year, Queen of the Desert, which stars Nicole Kidman and James Franco, should also hit theaters later this year. The filmmaker is also finishing up a much-anticipated new documentary, an epic 3D IMAX film called Into the Inferno, that travels to the sites of active volcanoes and explores the communities that are living in their shadows.

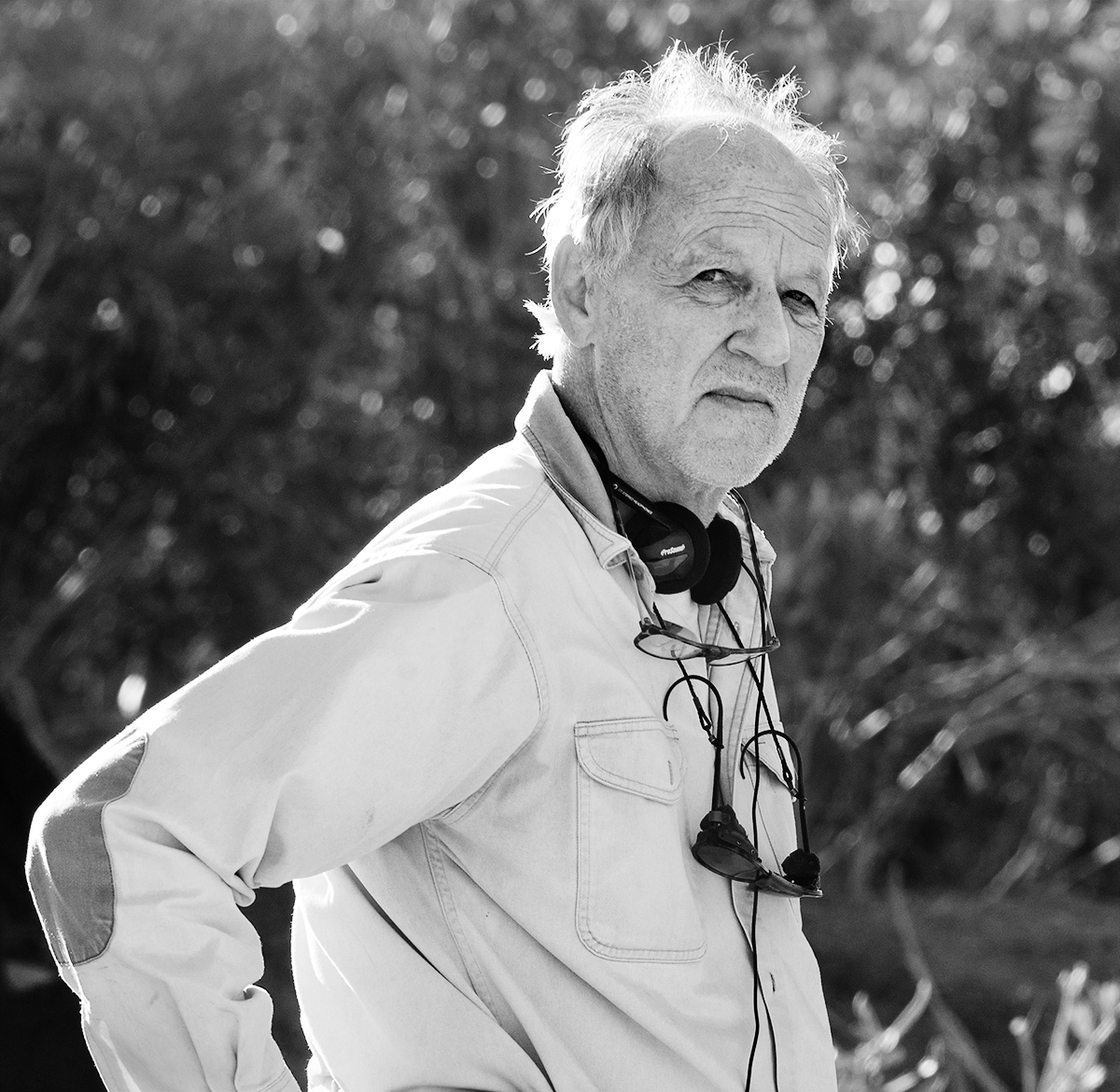

As for local audiences, this Herzog-ian overload will go one step further. The famed German director will appear live onstage at the Winspear Opera House on August 31 as part of the AT&T Performing Arts Center’s “Hear Here” conversation series.

Sheer volume of output aside, what is perhaps most remarkable about Herzog is that the longer his career stretches on, the more relevant he has become to international audiences. In the last decade, Herzog has turned into something of a pop cultural figure. He has enjoyed cameos on shows such as Parks and Recreation and The Simpsons and played the villain in Tom Cruise’s Jack Reacher. He will teach an online film course that promises to impart to subscribers everything they need to become a filmmaker within two weeks, offering advice like storyboarding is “an instrument of the cowards.”

Herzog has somehow managed to transcend his own reputation as a filmmaker, becoming, in the popular imagination, something closer to a modern sage—filmmaker as transcendental guru. He projects the persona of an avuncular figure who possesses a hard, uncompromising wisdom, earned in the trenches. “Fear is not in my dictionary” is a typical Herzog pronouncement, the kind of line that mixes a peculiar brand of ascetic remove and a Hemingway-ish brawn that can almost make today’s Herzog come off as a mystic Norman Mailer.

There was a time, though, when Herzog loomed as a more enigmatic figure in the world of cinema. There was nothing cozy or intellectually cute about his breakthrough film, 1972’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God, a fever dream of a story about a conquistador coming unhinged in the Amazonian jungle. The film itself seems to teeter on the edge, charged by a real—not staged—sense of peril, as if Herzog had figured out how to turn filmmaking into an extreme sport.

There would be no Apocalypse Now without Aguirre, which is only to begin to list the films and filmmakers indebted to Herzog. But the stories of how he went about making his movies became as much a part of the filmmaker’s reputation as their undeniable power and import. The screenplay for Aguirre was written, the story goes, when Herzog was a semi-pro soccer player competing in a low-level German league. He sat in a bus with a typewriter, banging out the script in a few short days while his teammates, celebrating a victory, emptied a keg of beer—and then the contents of their stomachs—all around him.

The stories continued. For example: for 1976’s Heart of Glass, the director hypnotized his entire cast for the duration of production. The most infamous production was 1982’s Fitzcarraldo. The story of an obsessive rubber baron who travels deep into the Amazon jungle in a quest to find a lucrative crop of rubber trees, the film climaxes with the madman capitalist-colonialist dragging his steamboat over a mountain. During the making of the film, Herzog had his cast actually drag the ship they were using in the production over a mountain. On set, there was also an attempted murder, a crew member cut off his own foot to save himself from a snake bite, and Herzog’s lead actor, Klaus Kinski, went mad.

Herzog’s reputation as a cinematic sadist, a filmmaker who was willing to exploit his cast and crew, grew. It was a reputation bolstered by the presence of the filmmaker’s two dramatic muses, Kinski and Bruno Schleinstein (often credited simply as Bruno S.). Kinski, who stared in Aguirre, Fitzcarraldo, and 1979’s Woyzeck, was mentally unstable, tempestuous, given to fits and ill behavior. Bruno S., the lead in 1974’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser and 1977’s Stroszek, was simple-minded, submissive, easily manipulated. These two actors capture the yin and yang of Herzog’s own eccentric imagination, in which compassion and cruelty often find themselves as unexpected bedfellows. You see this theme emerge again and again—blurred lines between sanity and madness, civilization and barbarism, art and chaos. Herzog’s films can be simultaneously stark, brutal, magical, and surreal. Both Kinski’s petty tyrants and Schleinstein’s holy fools work to turn the moral universe on its head.

[d-embed][/d-embed]

Herzog’s films undoubtedly offer a singular cinematic vision, but to fully appreciate their enduring appeal, it is worth remembering that his work also exists within the context of a broader project. Like the work of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Wim Wenders, Margarethe von Trotta, and other contemporaries who comprised the so-called New German Cinema, Herzog’s movies were forged by a uniquely German experience of the postwar years. Sadism, human cruelty, bourgeois indifference, the elusiveness of personal and spiritual freedom, a bleakly deterministic view of history, a pessimistic outlook on the project of human civilization—these are all themes rooted in an artistic struggle to come to terms with a particular historical horror story.

Sometimes it can feel as if today’s Herzog gets a little lost in translation. The German filmmaker’s personal eccentricities, his Teutonic stoicism, dry Bavarian wit, and easily parodied narrative monotone can come across as kitsch. But dig beneath the surface of his transfixing and sometimes beguiling new documentaries, and you can see that Herzog has found in nonfiction storytelling a genre that can enjoy a wider audience while still exploring many of the same themes and fascinations that powered his more combative, difficult, and elusive films.

The topics of these documentaries include material as diverse as Russian mystics, Texas death row inmates, prehistoric cave paintings, and wingnut environmentalists, and yet Herzog’s later-life narrative musings manage to explore the same boundaries between the tamed and untamed, civilized and wild. After all, who is Timothy Treadwell, the main character of 2005’s Grizzly Man, if not an uncanny mash-up of Klaus Kinski and Bruno S.? In Treadwell, Herzog finds an eccentric, self-appointed protector of grizzly bears who is both the victim and perpetrator of a perverse, tyrannical sentimentality.

It is the same grist that Herzog continues to grind in his cinematic mill, the same sensitivity to the enigmatic workings of the human soul, the same familiarity with the reality of the past that equips him as a prescient interpreter of an increasingly incomprehensible future. His secret is simple, really: a wary eye steadfastly fixed on the invisible line between the sacred and the profane. That will always be relevant.

A version of this column appears in the August issue of D Magazine.