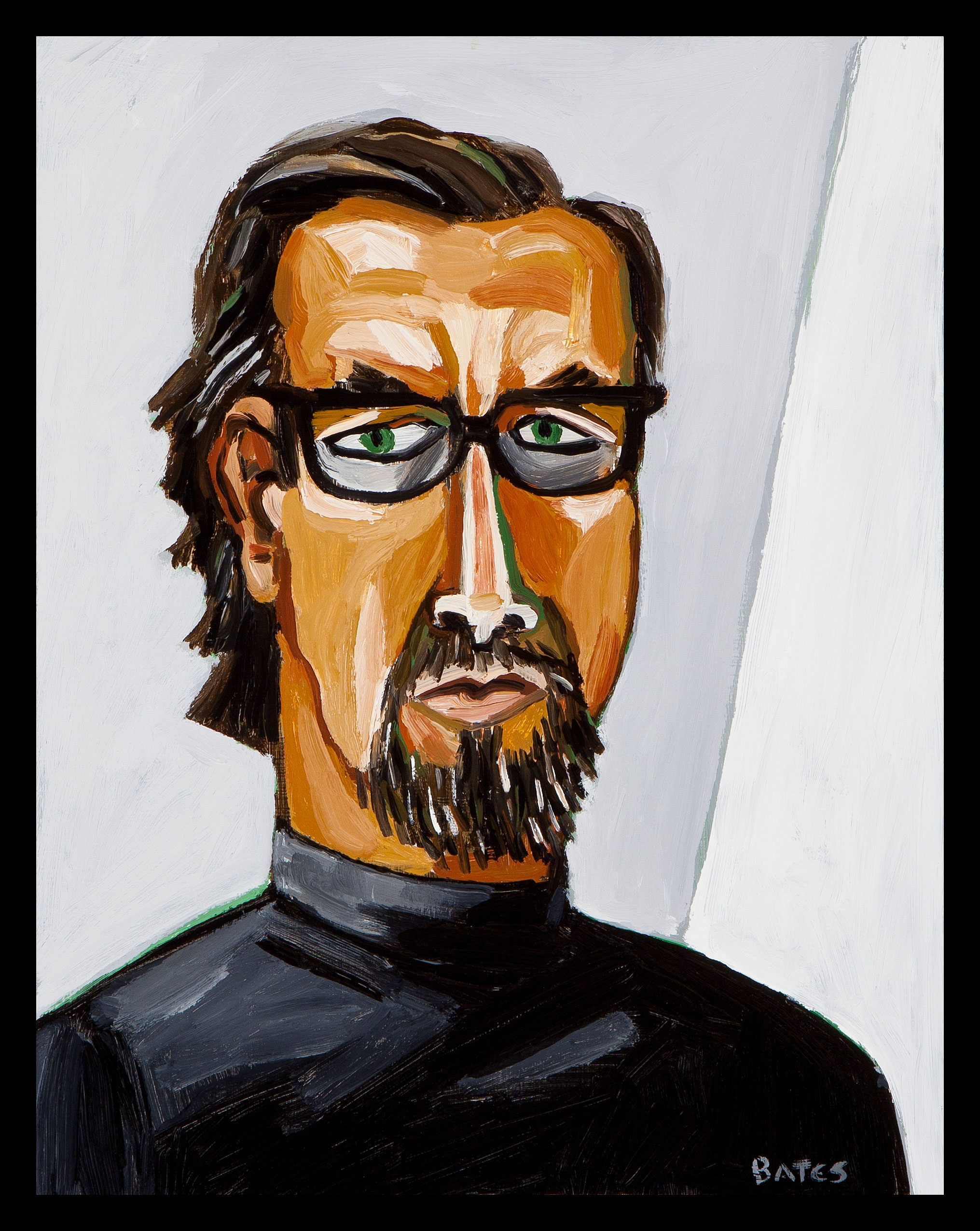

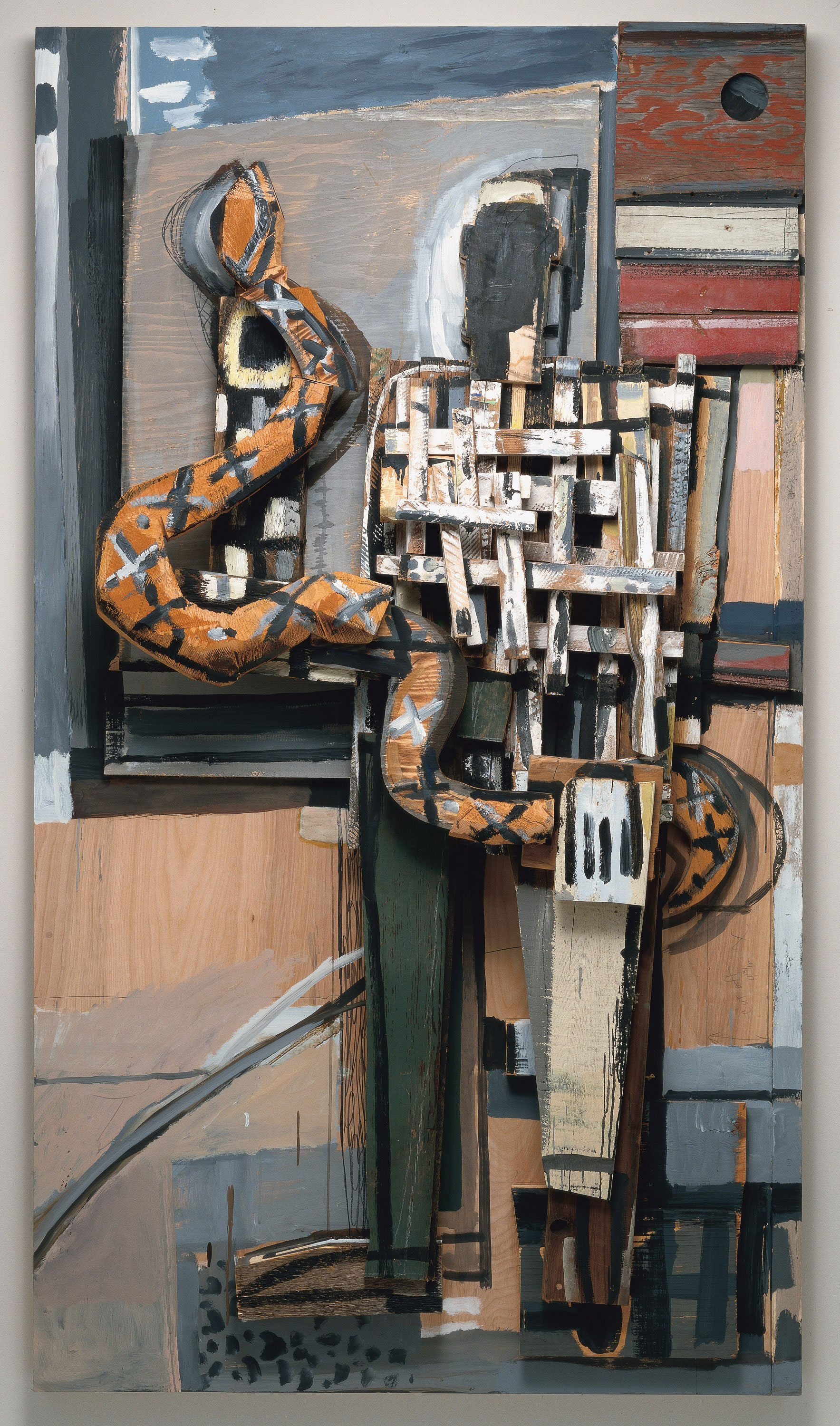

However, as much as Bates avoids intellectualism and admires the honesty and innate approach of the self-taught folk artists, he has a deep knowledge of art history, and the work of the past looms over his practice. In the corner of the storage room at Talley Dunn, there stands a sculpture of a nude woman posed with her arm arched above her head. It is an unmistakable quote from Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. It’s this engagement with the monumental artistic talents of the past that caught Nasher director Jeremy Strick’s eye.

“His historical ambitions become clear when viewed over the length of his career,” Strick says. “When he first emerged, on the one hand, there was such facility as a painter. On the other hand, the subject matter was so distinctly his own—effectively regional. And there was a relationship to folk art and folk imagery. The broader art-history ambitions weren’t as evident, but over time, he has taken on genre after genre.”

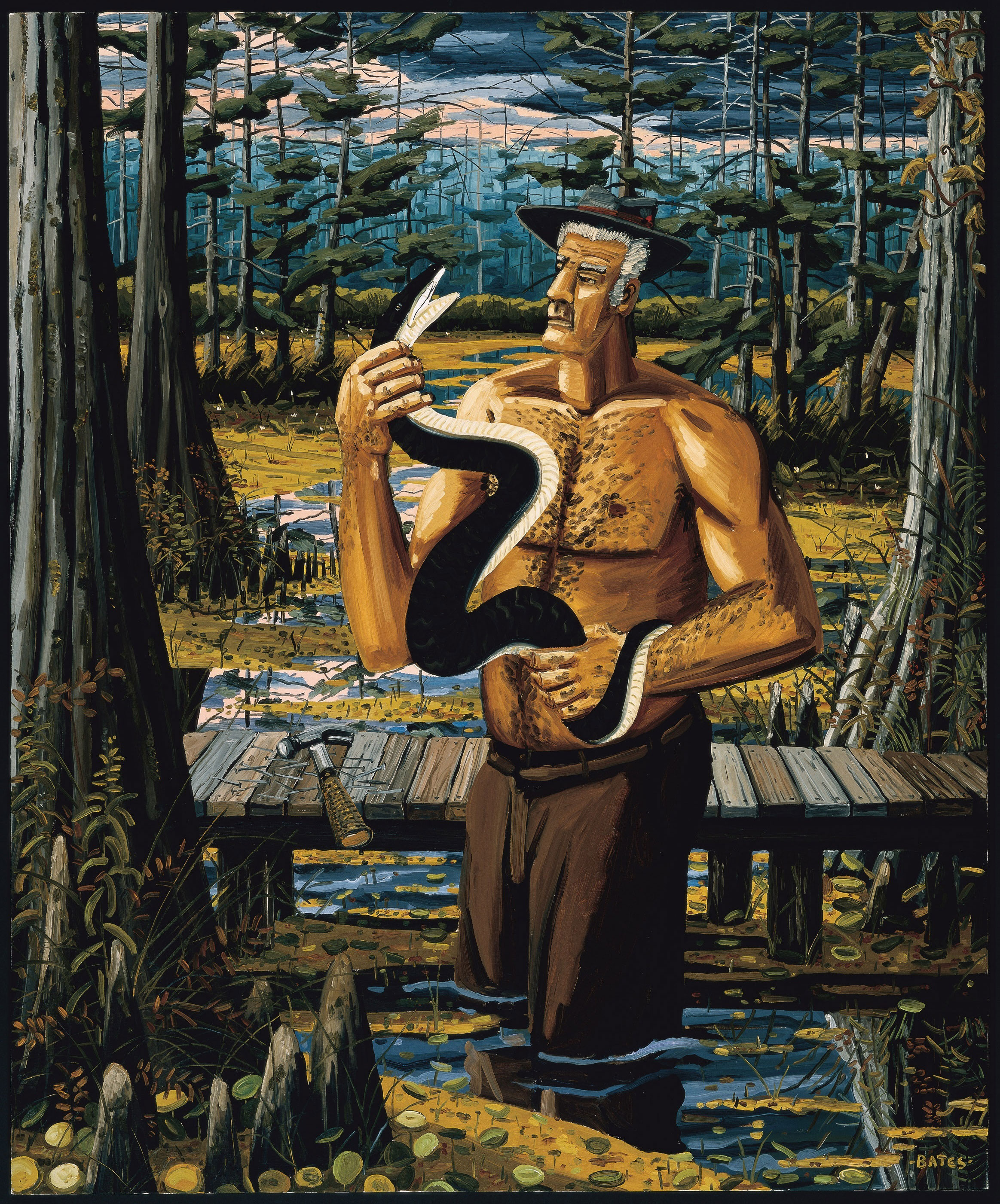

Bates has always tackled the “jazz standards” of painting—still lifes, landscapes, and portraits—but his more recent critical acclaim came when he created a series of paintings in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. In these works, Bates’ naturalistic romanticism gives way to a more singular emotional plea. His works are melodramatic—almost sentimental, teetering on voyeuristic—and yet what is striking is that they play in such contrast to the more sanitized and diffused visions of New Orleans in the days after Hurricane Katrina that made it onto the television airwaves. Somehow Bates found a gap in the news cycle’s continuous bombardment of reported images, where painting could find a place to, once again, tell its own version of history.

Bates has created a space for himself as an artist. He draws heavily from folk art, but he is not a folk artist. As much as he eschews high art pretension, he is working in dialogue with the breadth of art history. “Certain artists seem to be very connected to their place,” Strick says. “Their work speaks to something of that place, but you wouldn’t qualify them as regional. There is something that is quite distinctive and personal in Bates’ work, but there’s all kinds of modernist or even postmodern elements to the way he works: the subject matter, repetition, appropriations, the use of materials. All of those things put him in the contemporary world, even if he is an artist that made a choice to come back to Dallas. That reflects a desire to preserve and nurture his own identity at some remove from the contemporary art world.”

Bates embraces his sense of place, his position on the outside. And yet he’s bemused that there is a place inside and outside art in the first place. How is it, he wonders, that the South can be loved for so many of its cultural contributions, but art, somehow, doesn’t have a place in that conversation?

“It’s always been interesting to me in the South,” he says. “They have such a culture of writers, food, music, jazz, blues—all of it comes from down there. All of that stuff is so sophisticated, and so where’s the visual art team? Well, we all picked up and moved to New York because we didn’t want to sit around here and be losers.”

“The New York Times will review cooking from Louisiana, and they love going down and hearing some jazz, and will review music from Nashville, Austin,” he says, and then takes up a haughty voice of an imaginary editor. “But when it comes to ballet, symphony, or the fine arts, that’s where we stop. Now, y’all don’t know shit about that. Making ribs, whatever. But painting, dance. If you’re serious about that, you need to bring it up here. You can join the big leagues or quit. And you go, ‘Really?’ ”

Bates takes a rare pause, and then he laughs. He knows what he has done. We’re sitting surrounded by work that will soon decorate the walls of two museums. We’re flipping through a catalog that spans a career that has taken him into swamps and shrimp boats, museums and biennale pavilions alike. He had to fight through dismissiveness and ambivalence. But in the end, David Bates challenged conventional wisdom and won. Do you need to bring it up to the big leagues? Really? What big leagues are you talking about?

“I know it sounds like a loser from the flyover area, but every decade it seems a little bit more makeable,” he says, “that some guy can not show up to the party and say, ‘I’m going to have my own fucking party.’ ”