Bates’ time in New York was intense and bewildering. In the late 1970s, painting was dead again; video, performance, text, and other conceptual-based forms reigned. The students in Bates’ class at the Whitney program, including feminist conceptual artist Jenny Holzer, visited different artists every day. “It would be Alice Neel one day and Richard Serra the next day,” Bates says. “They would all come in and tell you how to do it, and any other way to do it was fucking bullshit.”

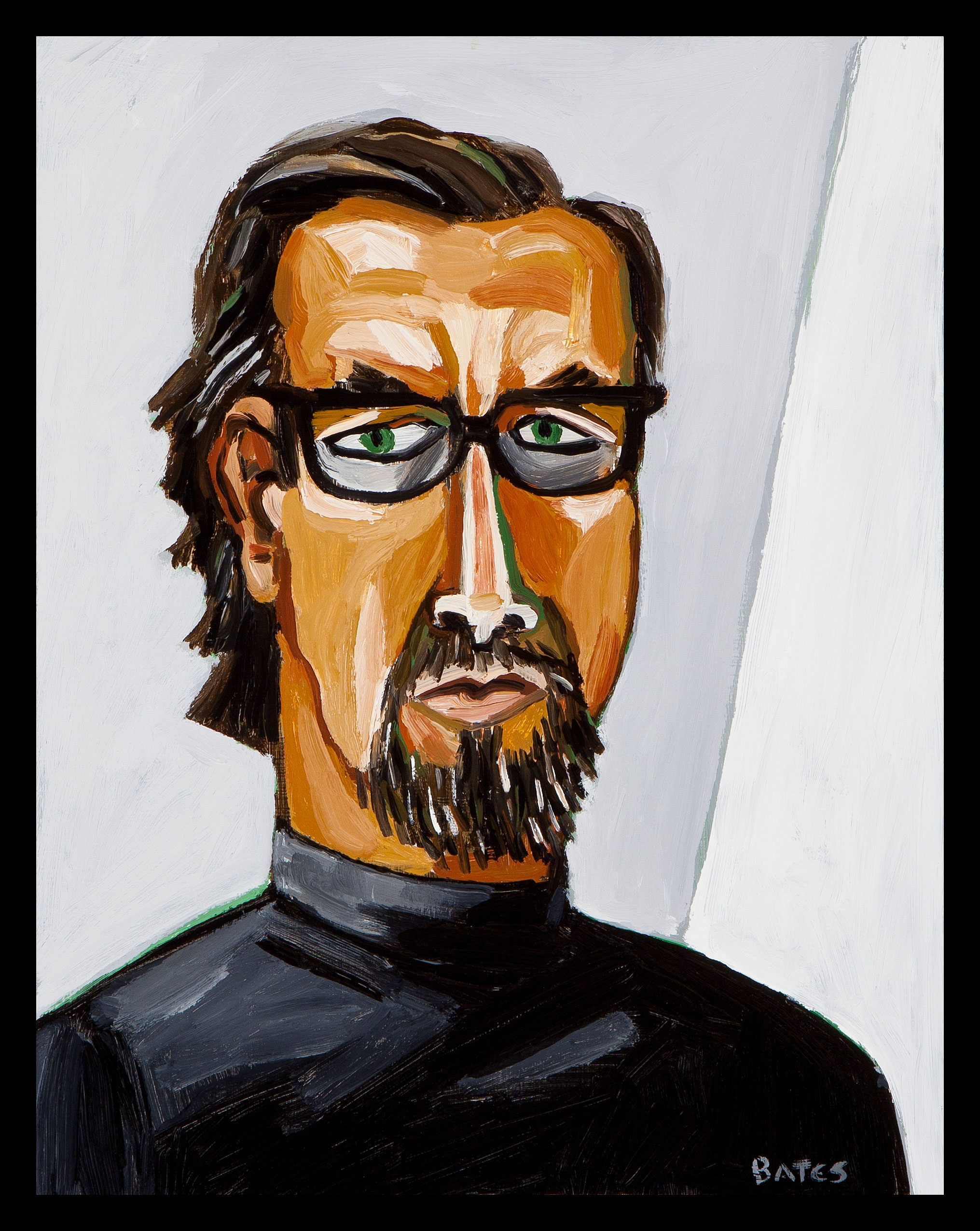

Bates’ paintings take up subjects with similar sensitivity of folk ballads and blues songs, Faulkner novels and Horton Foote plays.

The problem was that Bates still wasn’t sure what he wanted to do. He had a hunch, though, that he could figure that out back home in Dallas. “I came back, and I told Bob Murdoch, who was curator at the Dallas museum at the time, ‘Okay, man, I have a play for you. I have a performance. I have some videos,’ ” Bates says. “I was like, ‘Look, dude, I’m just trying to enlighten you with some brilliance from New York.’ ”

After returning from New York, though, Bates began to find the art that would really draw him in. He was teaching at a number of local colleges and audited a full slate of art history courses. He also met the artist and his future wife, Jan Lee McComas. McComas’ work drew from a heavy folk art influence, and that kind of work, often created by self-taught painters, rural mystics, and other outsider artists, helped reacquaint Bates with the simple pleasure and sense of play in making art.

“That’s the thing with those folk artists; they don’t care,” Bates says. “They are just taking some paint and throwing it around and seeing what it looks like. And those early Renaissance people were folk artists. Giotto. They didn’t know how to do that stuff. They have these profiles, and it’s just a two-dimensional face. They loved the charm of that.”

Bates was set. He had a good teaching job and didn’t have to worry about selling work to pay the bills. He had time to explore the countryside and experiment with new forms and techniques. His paintings during this period mix folk motifs, like the abstract patterns of quilts, with scenes reminiscent of European primitivism, painters like Henri Rousseau and Paul Gauguin. Meanwhile, the Dallas art scene was diversifying. The institution that would become The Dallas Contemporary opened, as did the state’s first artist-run cooperative, 500x. DW Gallery, which had started as an all-female art collective, gave Bates a solo show in 1981 that created a local stir.

A year later, he discovered Grassy Lake and began painting it in earnest. Bates’ career took off. In 1983, his work was included in exhibitions at the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston and the New Orleans Museum of Art, and he was chosen for the 38th Corcoran Biennial in Washington, D.C., an exhibition of American painters that proved life changing. His work would be picked up by former Artforum editor Charles Cowles’ gallery in New York and purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. By the end of 1984, his work was also in the collections of the Dallas Museum of Art and the New Orleans Museum. Success allowed him to quit his teaching job and focus full time on painting. For the next decade, he would regularly return to Grassy Lake.

•••

In the art publisher Phaidon’s Art USA, an anthology of American artists, Bates is represented by an image of his painting called Anhinga. It depicts a snakebird perched on a branch that bends over a watery landscape with an almost toxic glow. The bird’s long neck twists upward, pinching a tiny fish in its thin beak, holding the little critter high to soot-black clouds that gather ominously over the spiny trees of Grassy Lake. The text accompanying the image says that Bates “pictures the inhabitants of his hometown of Dallas, Texas.” For anyone who knows Dallas, the description reads like a punch line.

Bates doesn’t paint pictures of Dallas. In fact, his travels to unfamiliar locales are integral to his process. He visits places that inspire him—the swamp, the Gulf Coast—learning the lay of the land, befriending locals, accompanying fishermen on their shrimp boats, sketchbook in hand. Just as Gauguin traveled the South Pacific to watch the islanders and make paintings of their daily lives, so has Bates drawn from Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana versions of these subjects, people like the Grassy Lake fisherman Ed Walker. Flipping through Bates’ catalog, he is more likely to tell you a story about the person or the dog in the image than to go on about composition or form.

Likewise, it seems just as important to Bates that his work be understood by the people he paints. “What’s that, a painting of a beer and shrimp and cigarettes?” Bates says, affecting the accent of an imaginary Texan encountering one of his paintings. “Love it. I’ve had a shitload of that in my life. I’ll take that painting.”

Get the FrontRow Newsletter