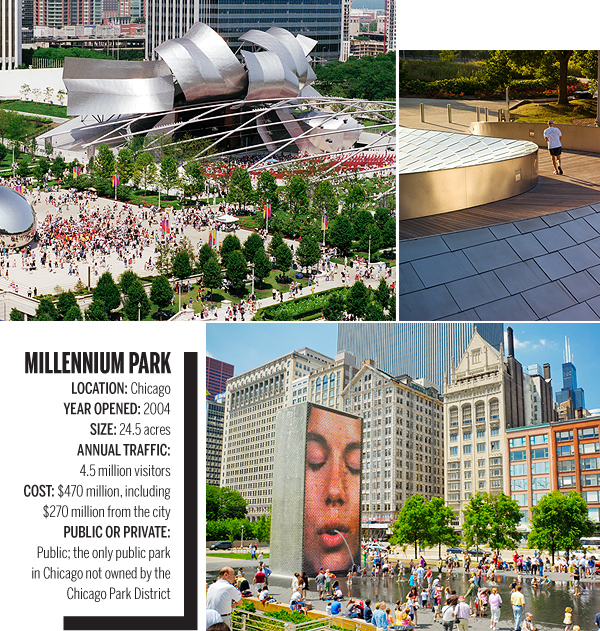

Take a walk around Chicago’s Millennium Park, and you’d have no idea that it rests on land that—even as recently as 15 years ago—was covered in railroad tracks, industrial sprawl, and parking lots. Originally planned as a parking complex over the tracks as part of a larger project, intervention from Mayor Richard M. Daley prompted a shift to a public park, and the race to beauty was on. The allure of the park, says executive director Ed Uhlir, is partly in its architecture. Park officials commissioned structures by multiple architects in an effort to “find the best in the world.”

Anchored by its Frank Gehry-designed bandshell, the park also includes designs by Renzo Piano—the architect behind the Nasher Sculpture Center—and Anish Kapoor.

The park offers hundreds of free events annually and is open 365 days of the year. It has brought $1 billion in tourism dollars and tax revenue to the city, Uhlir says, and raised surrounding property values by about $1.4 billion.

“There are a lot of things people come to Chicago for: the museums, the food, the shopping, the lake,” Uhlir says. “But Millennium Park is now another major element that is attractive when people are making a decision where to go.”

Not that the park isn’t without its issues. The original budget was $150 million, but ballooned to nearly $500 million due to cost overruns, old-fashioned Chicago cronyism, and poor planning. In an effort to make that up to Chicago residents, Uhlir has stocked the park with world-class art, pieces that draw visitors from around the world.

“It’s the one place you have to visit in Chicago, and everyone does,” he says. “If you’re from out of town, and you visit your friends here, the first thing you say is, ‘Can you take me to see Millennium Park?’”

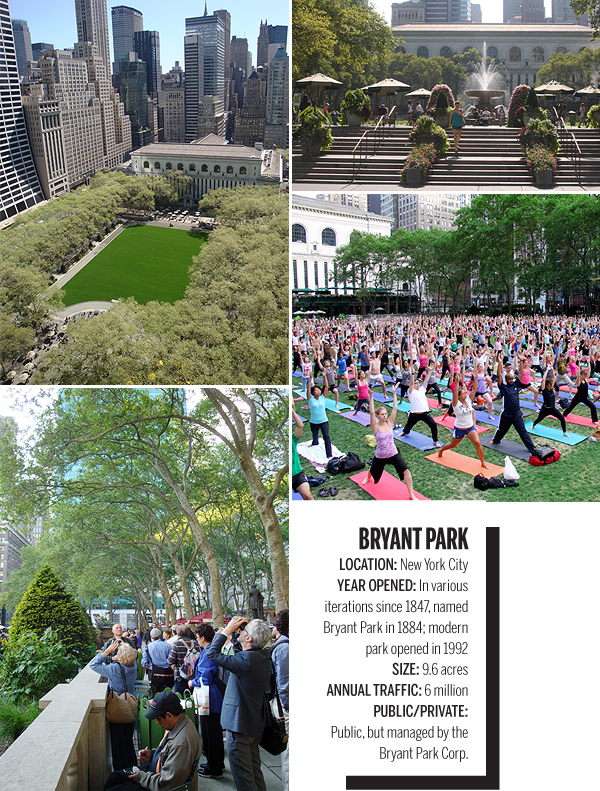

Any piece of green space in New York City is an amenity, even if it’s a chunk of Astroturf plopped in front of a bodega. That’s why Bryant Park—that anomalous little spot of heaven in midtown Manhattan—is so popular. Swing by any sunny day, and its wide lawn is full of workers, tourists, and truant students eating lunch or catching some rays.

Thirty-five years ago, it was the exact opposite. Overtaken by drug dealers and addicts, the city had all but given up on the park, a natural extension of the porn houses and grunge of nearby Times Square. Ad hoc cafes and book markets in the early ‘80s showcased the park’s renewed potential, and by the late ‘90s the park was again full every lunch hour, 4,000 visitors strong.

The Bryant Park Corp. deserves most of the credit. Long cited as one of the most successful public-private partnerships in the parks world, the corporation invested millions, fixing the park’s bathrooms and building a carousel.

BPC “turned a disaster into an asset, dramatically improved the neighborhood, and pushed up office rents and occupancy rates,” reads a 1996 Urban Land Institute report.

Since then, the park has only improved. The first NYC park to offer free wireless, Bryant Park now serves as a front lawn for many Midtown residents and employees. It’s Manhattan’s largest piece of open grass south of Central Park, hosting the HBO Bryant Park Summer Film Festival. Park officials even show Yankees games on the big screen.

Attracting more than 6 million visitors a year, it is, without doubt, one of the finest examples of urban regeneration in the country.

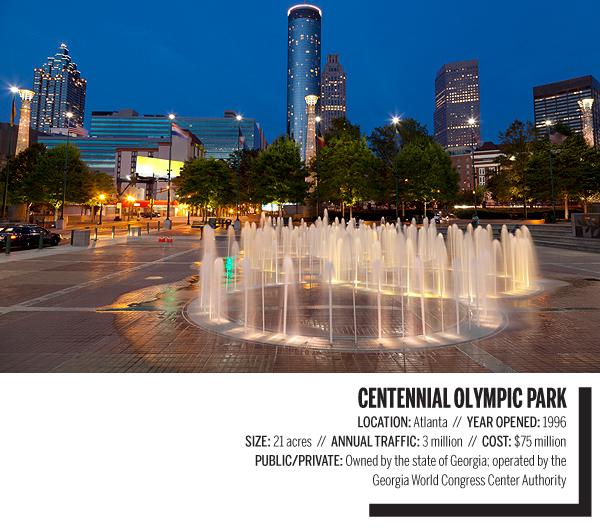

Somewhere in Centennial Olympic Park is a brick, engraved with something like “The Pearson Family” or “The Pearsons.” When Atlanta Olympic officials and private donors were raising the $75 million to build the park back in the mid-‘90s, they accepted donations, $35 at a time, for bricks engraved with whatever non-vulgar thing the donor could think of.

My family, 950 miles away in New York, bought one, etching our names into a piece of history. Close to 500,000 folks eventually bought bricks, enough to stretch from Klyde Warren Park to the Oklahoma border.

The park originally opened in 1996, welcoming tourists and athletes for the 1996 Atlanta Summer Olympics, dressed in their country’s colors, trading pins and other knick-knacks. Following the games, a large portion of the park closed for nearly two years, during which it transformed into a full-service public park. Remaining were the interconnecting Olympic rings, a water feature that shoots sprays 12 feet in the air.

In an effort to keep with the Olympic spirit, volunteers do much of Centennial Olympic Parks’ work, whether it’s serving as an information desk attendant, helping with landscaping, or aiding with the park’s Fourth of July celebration and weekly concert series.

The park has been a catalyst for development in downtown Atlanta and the neighborhood surrounding it, known as the Luckie Marietta District. Imagine It!, The Children’s Museum of Atlanta, opened in 2003, and The World of Coca-Cola opened near the park in 2007.

If you go for a visit, say “Hi” to my brick.

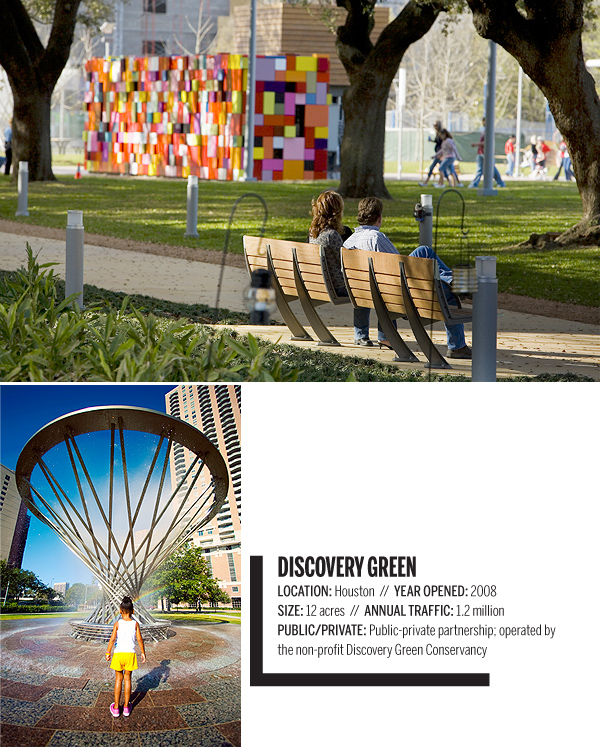

Many major American cities—Chicago, New York, Philadelphia—were born at a time when residents’ work, home, and entertainment lives were intertwined. You lived a few blocks from where you worked; you went to see a show two blocks further. Because of that, downtown areas of those cities have never wanted for attention. Newer cities—Dallas, Houston, Phoenix—developed later, when cars and trains could transport their residents across a city, or to a suburb.

That’s why Discovery Green is such a sea change for Houston, and has grown into a major hub of activity within the city.

Initial projections of the park’s use were near 500,000 annual visitors; in four years those numbers have climbed to 1.2 million. It has resulted in a new sense of civic and downtown pride for the city, says president and park director Barry Mandel.

“We’re really careful of the programming that happens during the day, because of the huge office tower across the street, and we’re careful of the programming that happens at night, because we have a huge residential tower next door,” he says.

Those activities included outdoor movies, speaker series, exercise classes, even kayaking. The park’s creation has led to nearly $500 million in nearby construction, Mandel says.

His biggest issue, though, is convincing people to sustain that growth. The park is not technically a Houston city park, so money comes from private donations and grants, instead of tax rolls.

Says Mandel: “It’s getting people to understand I don’t need $5,000 from you, but I do need $5 from you every once in a while.”