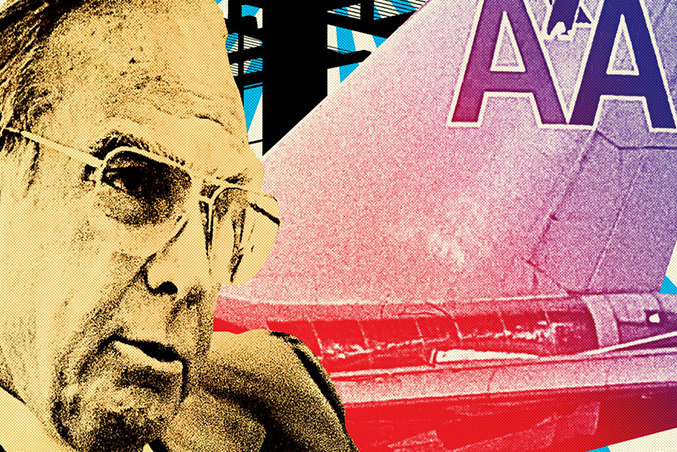

Everyone on both sides wanted American Airlines to relocate its headquarters to the new Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, from the various political and civic leaders in both cities to American’s corporate brass. Everyone, that is, except New York, where the airline had been based since 1930. Mayor Ed Koch called the departure a “betrayal,” and behind the scenes, all manner of political pressure was brought to bear in an attempt to block the move. It almost worked. But DFW was not without its own political allies. Over the Christmas holidays in 1978, senators Lloyd Bentsen and John Tower were enlisted to come home to the front lines. Fort Worth congressman Jim Wright, the majority leader of the House of Representatives, was an even bigger friend to DFW and American Airlines. Not only did he help clear the way for American’s arrival, he also introduced the Wright Amendment in 1979, which constricted air traffic at Love Field for more than two decades.

The Civil Aeronautics Board, the agency of the government that authorized and certified flights into and out of airports all over the United States, had early on (in the 1960s) said to Dallas and Forth Worth that they could not certify any more flights unless they absolutely promised to close Love Field and Greater Southwest International Airport and Fort Worth International Airport, and to concentrate all their flights into one midway facility. That is what the CAB ordered them to do, and they set about the business of doing it.

The cities of Fort Worth and Dallas, through their city governments, passed ordinances closing Love Field, Greater Southwest, and Meacham Field. They brought in a bond commission that they set out to sell bonds to help the cities finance this new airport that was going to be the third-busiest airport in the world. In exchange for that, the FAA authorized and put in millions of dollars of federal aid to help build this huge airport: now Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport.

It was a deal that I had something to do with helping them all put together. It wasn’t my initiative that started the whole thing. It was the federal agencies saying that they weren’t going to continue to serve Dallas and Fort Worth separately. Love was closed by the city of Dallas. Meacham and Greater Southwest were closed by the city of Fort Worth. So the federal government released these funds, and we built the airport and a magnificent thing for us it has been.

After that, everything was going along swimmingly and fine until Southwest—which came into being in 1971—went to a functional agency of the state, known as the Texas Aviation Commission, and appealed. The Texas Aviation Commission ordered the city of Dallas to open up Love Field for Southwest Airlines. Dallas did so under order of the state. I don’t suppose it had any alternative. But it was on rocky ground because the cities had sold bonds to pay for DFW, and the bonds, every one of them, had a promise that there would be no commercial airline flights out of any other airport within a 20-mile radius of DFW Airport. That’s what the bonds promised, and that’s what was promised to the federal government in exchange for the millions of dollars we got from them.

So something had to be done. The airline deregulation bill came along in 1978, and the CAB was going out of business, but the FAA was taking on all the responsibilities of safety and airport construction and airline safety measures, including air traffic control operations. And the regional head of the FAA told me personally that he was not going to allow any federal aid or assistance to be given to any airport that flew big planes in landing and takeoff routes that overlapped with DFW. In the view of the FAA, it was a safety hazard.

It was 1979, and both cities came to me saying, “Please, do something.” So I put an amendment, offered an amendment to the bill in the House. And it passed the House. And the bill said there would be no commercial airline flights scheduled out of Love Field or Meacham Field or Greater Southwest, which of course was just attached to the south of DFW. That’s the way it passed the House, and then it got over to the Senate, and Southwest and some of the other airline people came up to testify in the Senate.

Southwest made a case to me that they had invested money at Love Field. They wanted to be able to fly out of Texas, but the state agency’s ruling applied only to intrastate flights. That state agency had no control whatsoever for destinations outside the state of Texas. They could literally have gone to DFW and flown anywhere they wanted to, but they chose not to. They said they needed to recoup their investments at Love Field.

Well, Herb Kelleher and I got along fine personally. I did not want to punish some legitimate business that had gone into operation under the rules and laws of the state of Texas. But I had a responsibility to the FAA, which at my urging and insistence had put out the money to build DFW, and to the bond holders who had bought the bonds from the cities of Fort Worth and Dallas, who were Forth Worth and Dallas citizens, most of them.

So I sat down with several presidents and heads and chairmen of the boards of several of the airlines that were involved. DFW had been in operation for five years by ’79. But Southwest was in operation in Dallas, and I wanted to be fair to everybody. So we agreed, ultimately—it was a kind of give-and-take proposition—and we started to compromise. Henry Clay said that “compromise is the cement that holds the Union together.”

I want everyone to understand that I am a peacemaker between Fort Worth and Dallas. I strive to be the dove of peace. I don’t want anyone to think I’ve got anything against Dallas. The three happiest years of my public schooling as a youngster were in Adamson High School in Dallas.

So we compromised, and we comprised what is now known as the Wright Amendment that passed both houses. It said there would be no commercial flights from Dallas Love Field except to and from destinations within the immediately adjoining states: meaning New Mexico, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana. That was the solution we came up with, and Southwest was as happy as a clam. I think Herb felt like he had died and gone to heaven when he got that. And I thought that settled it.

It was a compromise, to be sure. It was not a full fulfillment of the pledge that the cities had made to the FAA. But it was in good faith, and it satisfied the requirement by the FAA that there be no big flights in and out of Love Field because they interfered with the landings and takeoffs at DFW. So we thought we had it all worked out and satisfied. But it didn’t long satisfy the Southwest people.

The last time I was at Love Field, a few years ago, they had a great big billboard stating “Wright is wrong.” I was going to Austin, I had to be there for a funeral of a dear friend of mine, and this was the only flight to get me there on time. I went up to the ticket window inside the terminal, and the lady looked at me rather strangely and then said, “We’re asking each of our passengers today to sign this petition, if you would, petitioning the government to repeal the Wright Amendment.” And I kind of smiled, and I could see by the look in her eyes that she recognized me. I said I would be honored to sign up with the proposition except that I was so busy writing notes of congratulations and good wishes to my dear old friends, such as Herb Kelleher. And she said, “Well you wait here just a minute,” and she went and got Herb.

We’ve been friends a long time, in spite of some of the people in Dallas thinking I was discriminating against Southwest. That wasn’t my intention. I think Herb would tell you that the exceptions I agreed to in the amendment kept them in business for a little while.

But they finally worked it out and got things through, I think, in a satisfactory manner. I’m happy with it if the people who provide airline service are happy, if people who fly the airlines are happy, and if safety is served. I’m content and happy that we were able to get through that period and get the airport going good and strong. As I said, I think today that DFW is the third-busiest airport in the world.

It took an awful lot of give-and-take on the part of an awful lot of people.

Jim Wright, former speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, is a member of the political science faculty at Texas Christian University.