Working as a young reporter for a business-newsletter company in San Francisco in the 1980s, I learned two things that made a lasting impression. Both came courtesy of the company’s founder—a hard-driving, whip-smart former mortgage broker. And both seem relevant to the financial drama we’ve witnessed these past few months.

The first involved the herd mentality as applied to business trends. If developers in a given market have success putting up one property type—garden apartments, say, or office/warehouse space—many others will rush to join them, leading inevitably to a glut and then a correction. Farmers do the same with the latest hot crop.

The second concerned various financial instruments such as collateralized mortgage and debt obligations. Like Eskimos butchering and using every piece of a dead walrus—blubber, meat, tusks—Wall Street sliced and diced these instruments for sale into infinite numbers of tranches, each with its own maturity or risk class. This kept fresh money flowing into the system, and I thought it was genius.

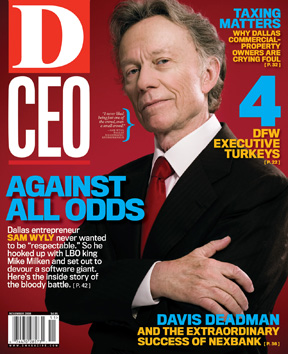

These things came back to me recently watching the “Wall Street” crisis unfold and editing the excerpt from Sam Wyly’s new book that appears in this issue on page 42. The 1980s takeover battle that Wyly writes about was fueled by Mike Milken’s high-yield bonds, which themselves helped unleash untold prosperity, yet wound up being blamed at least in part for a “culture of excess” that led to a massive government (read: taxpayer) bailout.

Sound familiar? It should. That’s because today’s crisis seems like a replay of the ’80s-early ’90s fiasco, when ill-conceived federal regulation helped put hundreds of S&L lenders out of business.

Instead of letting the market work again as it should, this time around the “solution” first proposed by Washington was even worse than two decades ago: virtually nationalizing much of the nation’s financial sector, like some tinhorn dictatorship.

The key to our current problem wasn’t a failed marketplace, though. It was easy money and the hyper-politicization of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Nourished and protected by their huge political contributions to D.C. movers and shakers, these quasi-governmental entities encouraged home ownership to riskier and riskier borrowers by owning or guaranteeing hundreds of billions of dollars in high-risk mortgages. They were abetted, to be sure, by the whole system: ratings agencies like Moody’s; ill-advised, Enron-inspired mark-to-market accounting rules; and community organizers like ACORN, who cried “redlining” as they basically blackmailed banks into lending to unqualified borrowers.

When housing prices stopped their steady upward march, the chickens came home to roost.

And, once again, instead of pinching the true fraudsters and letting the market punish bad decisions, we’re hearing the familiar calls for more big-government regulation.

Smart, prudent new rules are fine, if they’re really warranted. But why throw the baby out with the bathwater? To sort this out, I’d sooner trust businesspeople and the free market—with all their failings and all their genius—than corrupt, incompetent pols on Capitol Hill any day.