THE REAGAN Administration has spent a lot of time cutting and raising taxes. The question is, after the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 (ERTA) and the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982, where do you stand with tax shelters? Do you still need them? The answers depend on your income and other possible deductions. If, after allowing for home mortgage interest, charitable contributions, losses and ad valorem taxes, you still think you’re paying too much tax, you may want to shelter some of your income.

The IRS hasn’t always taken a sanguine view of tax shelters, which, in fact, have often involved something of a chess match between tax payers and collectors. Even so, ERTA appears for the first time to put the tax code on the side of certain kinds of tax shelters as legitimate tools for both increasing disposable income and promoting investment activity and capital formation, the sources of future tax revenue.

Signed into law a year ago, ERTA is an outgrowth of tax legislation that was introduced in 1978 by Congressman Jack Kemp and Sen. William Roth. Their highly publicized Kemp-Roth scheme proposed an across-the-board cut in personal income taxes of 10 percent a year for three consecutive years. What actually emerged after congressional debate and compromise was a 23 percent aggregate reduction during three years with staggered cuts implemented October 1, 1981, and July 1, 1982. These total 15 percent. The third cut of 8 percent is due next July 1.

In overall concept, ERTA is one of those pieces of tax legislation that claims that less is more – that less tax burden on the individual leads to more personal savings and investments. These, of course, are the sources for capital formation to create jobs and build plants, which, in turn, create additional sources for more tax revenues. The concept is not farfetched and, if shown to be workable, could be extended even further to reduce the public’s use of tax shelters.

For example, Nobel laureate Milton Friedman proposes that the top personal income tax rate be limited to 25 percent, instead of the present 50 percent ceiling and the pre-ERTA 70 percent ceiling. Friedman predicts that slashing the top rate would ease the worst of the income tax’s burden with little or no revenue loss. He points out that in 1977, only about 13 percent of all federal revenues came from personal income tax rates above the 25 percent mark. Friedman argues that making 25 percent the maximum tax rate (for individuals and married couples, not necessarily corporations) could produce even more revenues for the government by eliminating the attractiveness of revenuedraining tax shelters, which all too often have had little real economic value.

Concepts require time to prove out, of course, and there’s probably not a Democrat campaigning this election year who cannot claim accurately that federal tax revenues under ERTA will be less this year than last. Hence the bill last summer to raise revenues through certain new taxes and procedures. ERTA watchers are still hoping that the investment-savings incentives put into effect in 1981 will begin to pay off in growing federal revenues. Many of those revenues are expected to come from several new types of tax shelters that ERTA permits and even encourages.

Perhaps the best-known of these new types is the Individual Retirement Account (IRA)-which Dallas banks, savings associations, credit unions, insurance companies and investment firms have pounced upon like ducks on a June bug. IRAs are the “everyman’s” tax shelter because there’s usually no minimum entry amount, the individual can sock away up to $2,000 a year ($4,000 for working couples) and the money can be both deducted from current income and can earn tax-free interest until withdrawals begin after the person reaches age 59 1/2.

While IRAs are more appropriately considered tax-advantaged accounts, most of the other ERTA-allowed tax shelters are tax-advantaged investments, replete with the risk-reward uncertainties of any investments, including the older types of tax shelters. And there are usually higher minimum entry fees – from $2,500 to $5,000 and up-and certain minimum “suitability” tests for income and net worth that investors have to meet.

“It would depend on an investor’s suitability whether he would go into a publicly registered partnership or a private placement,” says Dallas-based financial planner Cecil Lain. Most shelters, old or new, are limited partnerships in which investors-the limited partners – put up the bulk of the money. They usually have to show a lot of bulk before they can participate.

“People with annual incomes of $85,000 and up and a suitable net worth – say, $250,000 and up, excluding the home, automobiles and home furnishings – generally would be suitable investors for private programs,” says Lain, who helps syndicate both public and private partnerships in Texas for the broker dealership of New York-based Integrated Resources, Inc., listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Integrated Resources’ investor suitability criteria closely parallel those of many brokerage houses syndicating deals.

“Smaller investors would generally go into public partnerships [registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission],” Lain says. “On public programs, you could generally get in for $5,000 or thereabouts [as compared to $30,000 or more for most private placements], and you could get in for minimal net worth and income. A public oil and gas participation, for example, might require you to show a net income of $60,000, but a public real-estate participation might require only $25,000 to $30,000 net income.”

If any of those figures seem discouraging, there’s another way to “poor-boy” limited partnerships. Most brokerage houses have established IRA plans for their customers, allowing them to invest in mutual funds, limited partnerships, insurance annuities or securities of their choice, through a self-directed account. The customer pays an annual fee – usually no more than $50 – plus ordinary charges for any transactions he initiates. The hitch is, IRA-invested money is not available for use before age 591/2 without incurring immediately payable income – not capital gains – taxes plus an IRS-mandated 10 percent penalty.

THE FAVORITE types of tax shelters remain as they always have been – real estate, oil and gas drilling programs and equipment leasing. However, in the post-ERTA era, Lain says, “each of your traditional areas has been given an upward thrust in terms of attractiveness. ERTA has changed the return on investment dramatically, particularly in the area of real estate.”

The new shelters still do what shelters have always done: generate write-offs that reduce taxes on salaries or on income from her investments. For those persons in a 50-percent marginal tax bracket (the cutoff earnings figure above which half of everything you earn goes to Uncle Sam), the write-off alone can be of considerable worth. For example, with oil and gas shelters, an investment of say, $100,000, in exploratory drilling could result in a writeoff of 60 to 100 percent of the investment the first year just from so-called “intangible drilling and development costs.”

But if a well doesn’t pay – historically, 75 percent do not (in terms of returning the full amount of investors’ capital) – you might as well be pouring money down a rathole.

“If you’re just looking for a tax shelter, just loan me some money and 1 won’t pay you back. The only good tax shelter is one that makes money,” says Charles R. Hodges, marketing vice president for National Data Communications, a Dallas hospital computer firm.

Several investment advisors agree:

“I don’t even care to use the term, ’tax shelter,’ ” Cecil Lain says. “I believe that tax-advantaged investments have economic substance beyond the tax savings. Otherwise, they’re just not worth looking at.”

“The fundamental rule for a tax shelter is that it be a good investment,” says Larry Sisson, vice president and Dallas-based regional manager for Kidder Peabody & Co. “There’s been some really squirrelly deals come down that make you wonder what made people get involved in them. For example, any time you get offered a multiple write-off- say, you’re asked to put up $10,000 and they feel you can write off $40,000 or even just $20,000 – beware of that deal.”

Multiple write-offs were one of the problems, or abuses, that earned tax shelters considerable bad publicity in recent years. Most of the publicity has been aimed at abusive tax shelters – investment schemes with little economic substance where the available tax benefits are the only reason for investing. The new shelters, however – as well as their representatives – promote soundness of investment first, tax write-offs second.

They do so through a kind of carrot-and-stick proposition. The stick, found in a couple of ERTA administrative provisions, is provided courtesy of the Internal Revenue Service, which virtually guarantees an audit of any investment program suspected of overstating the purchase price of its underlying properties (thereby allowing investors to overstate the worth of their investments and the write-offs deriving therefrom). ERTA authorizes the IRS to impose a penalty on an underpayment of tax resulting from a valuation overstatement on returns filed after 1981. Depending on the amount of the overstatement, the penalty can be as much as 30 percent of the unpaid tax. Additional interest penalties tied to the prime lending rate prevent the wayward or negligent investor from making time and/or inflation work in his favor during the period of his tax delinquency. The lesson of the stick is that if a broker offers you a shelter deal that looks too good to be true, it probably isn’t.

The carrot is provided by alterations in the size and timing of write-offs in the new shelters. In real-estate investments, for example, depreciation schedules on commercial and industrial properties have been reduced from 30 years or more to only 15, allowing not only faster depreciation write-offs but also the opportunity to use the larger write-offs to offset income produced by the shelter itself.

This Accelerated Depreciation Recovery (ADR) feature of ERTA-also available to certain types of equipment-leasing shelters – has been particularly well received in Dallas, where commercial industrial developers seemingly remain oblivious to a recession. Cecil Lain’s organization has put together private placement financing of such local projects as the Neiman-Marcus store in Prestonwood Town Center, a Sears warehouse in Garland and a United Technologies plant in Carrollton, with salutary effects for the businesses served as well as for the individual investors.

“We’re seeing a lot of sale-leasebacks being made,” Lain says. Instead of having a lot of capital locked up in a building, a company can commit to build it, sell it to a shelter-oriented investor group and lease it back from the group. Everybody wins, theoretically. Investors have the depreciation write-off and continuing lease income. The company has the use of its money for capital formation.

Several large brokerage houses, including Kidder Peabody, take a slightly different investment tack, which uses existing properties to generate cash flow that will be sheltered in the main. With Henry S. Miller Co., Kidder Peabody is completing the first of a possible series of public placements that could give Dallasites the opportunity to share in the income and appreciation growth of parcels of their cities’ prime commercial property. A $20-million placement just completed packages several commercial projects, including office buildings and shopping centers.

THERE ARE certain rules-both written and unwritten – that may be used to guide the novice investor through the pitfalls of tax sheltering. Charles Hodges explains what he’s learned in the 40 percent-plus tax bracket:

“There are two rules I follow. The first is that the only good tax shelter is one that makes money. The second is that you should either know a lot about the business being sheltered or know a lot about the people involved or both.”

Hodges hedges his rules with additional advice, also endorsed by most professional shelter-investment managers: “I don’t think you should get into a tax shelter without the advice of your individual tax consultant, accountant or tax attorney. Also, you must be able to have a lot of confidence and trust in the shelter operator because people who use shelters are busy people who have to put reliance on other folks. They’re off doing other things nine or 10 hours a day.

“Exotic tax shelters [cattle feed lots, institutional dinnerware, Bibles, etc.] are usually to be avoided. The exotic will get you involved with the IRS. I’ve never known a person involved in an exotic tax shelter who wouldn’t have been better off just paying the taxes.”

Hodges seemingly contradicts this last piece of advice with the admission that for more than a year he has been involved in what might be deemed an “exotic” shelter – production of five pilots for a children’s television series modeled on the popular PM Magazine and intended for sale or syndication to network or cable.

It’s going to be an “all or nothing” situation, Hodges says, and “a lot of the way we’ll be treated |tax-wise] depends on whether [a certain interested network] buys the concept and pilots or involves us in producing the program on an ongoing basis.” Hodges got involved in this investment, he says, because of its social and commercial worthiness, a longtime personal awareness of the producer’s work, an acquaintance with the industry gleaned from following the career of his actress-model wife, the advice of a personal tax consultant and the fact that the deal had only about eight knowledgeable limited partners. “Also,” he says, “it’s been a lot of fun.”

“Fun” is a perfectly valid investment criterion as long as it’s figured into an investor’s overall financial objectives and “emotional risks,” Cecil Lain says. He cautions, however, that ability to play can have rather direct linkage to ability to pay. “There’s an old expression about investment risk that says, ’At 8 percent [investment] return you eat better, but at 6 percent you sleep better.’ Determining which of those you want comes from sitting down with a competent advisor.”

The competent advisor, he says, keepsone overall goal in mind: “The potentialreturn on that tax-advantaged investmentafter tax has to be greater than the returnthat person could have gotten elsewhere.”

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Hockey

What We Saw, What It Felt Like: Stars-Golden Knights, Game 4

The series is back on.

By Sean Shapiro and David Castillo

Local News

Leading Off (4/30/24)

Partly sunny today, with a high of 85 and chances of justice

By Tim Rogers

Local News

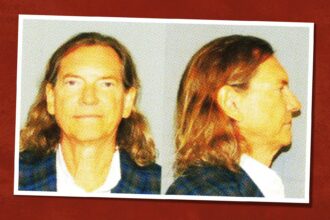

Bill Hutchinson Pleads Guilty to Misdemeanor Sex Crime

The Dallas real estate operator and erstwhile reality TV star will serve time under home confinement and have to register as a sex offender.

By Tim Rogers