ANALESLIE MUNCY was named for two grandmothers, Anna and Leslie. Her parents wanted to keep peace. Her maiden name is Unfried. No, not “fried,” as in fried chicken. It’s F-R-E-E-D. Kids used to tease Analeslie about her last name, and it really bothered her. She still regrets that her two younger brothers couldn’t change theirs to something like, well, Muncy. Muncy is a name that’s respected around Dallas City Hall. Especially now that Analeslie is the new city attorney, the first female to hold that job and only the fourth city attorney in 50 years.

Analeslie Muncy was appointed by the City Council to succeed Lee Holt, who’s retiring; she was his first assistant. City attorney is a glamorous job. At the top. Good money. Everyone asks for the opinion of the city attorney. There’s a penthouse view. Bright, attractive men. And, some say, considerable power. So here is this soft-eyed brunette in a plaid skirt, blue pumps, blue blazer and white blouse, running what, on some days, is the most important law firm in Dallas. No one would dare say that the city attorney has nice-looking legs.

Muncy is just back from Austin. She has barely had time to digest Percy Foreman’s speech on insanity pleas at the State Bar meeting or shelve work she’s doing on a Senate committee that’s studying fees and grants. Congratulatory flowers and notes about her appointment are still around. On her desk, two big books every bit as thick as The Joy of Cooking are staring up at her. She puts her palm on one like a preacher at a tent revival and says, “I’ve done 99 percent of the submissions to the Justice Department on voting rights in this city. That’s what these books are about. I’ve worked on them since 1975. We just got our clearance Friday from the Justice Department on this one. We may still be sued, but at least the department has cleared it.”

Muncy didn’t go after this job. It just happened. “I never had any ambition to be the city attorney. I always just enjoyed the heck out of whatever I was doing. I did feel a responsibility, though, in having held the position of first assistant. It would be extremely difficult for someone to come into this office from the outside. There is just so much to know.

“Our direction is being shaped by the Supreme Court. Ten years ago, a municipal attorney wouldn’t have been concerned with antitrust, but now he’s right in the middle of it.” Independent cab operators, for instance, are suing the city concerning its cab policy at D/FW airport. Muncy was also heavily involved in the suit by Dallas and the U.S. government concerning Irving’s use of Dallas’ floodway as a landfill. Dallas and the feds won, which meant that Irving had to pick up all its garbage and find someplace else to dump it.

“The courts have loaded us with all kinds of responsibilities in very complex areas of the law,” Muncy says. It used to be, in Henry Kucera’s day in the Forties, that a handful of attorneys did everything, including driving Kucera to get his weekly haircuts.

“Dallas has definitely changed,” Muncy says. “The catalyst was single-member council districts, something I worked on. It was a transition that started in the early Seventies with a lawsuit and ended in 1979. Before we had single-member districts, the City Council meetings lasted about an hour and a half. Everything was routine. Now, both sides [of an issue] are argued. Things are analyzed more. More public hearings are held, and people are more interested in what the city is doing.”

Muncy says she won’t do things much differently from Holt -that she’s comfortable with the way things are. “This is a legal position,” she says. “We provide advice, assistance and representation to the city council and various city departments. I don’t view it as a position of power.”

The word around City Hall is that Muncy was clearly the best choice for the job. People say she knows her stuff, a little like a squirrel who not only knows exactly how many nuts he has hidden for the winter, but also knows where he has hidden them. Hers wasn’t the only name that came up when recommendations were being made. Two other assistant city attorneys, Carrol Graham and Joe Werner, were interviewed by the screening committee. They told the questioners they didn’t want the job. Werner, who was in law school with Muncy, says Muncy was the best choice: “She’s highly organized and has a good analytical mind.”

City Council member Lee Simpson will be working closely with Muncy and her staff. Also an attorney, Simpson says he’s learned something from Muncy on how to advise his own clients. “She gives her legal opinion clearly and directly. She is fiercely independent and doesn’t mix policy with legal advice. She doesn’t bow to pressure.”

“I have a great deal of respect for her,” says Barry Knight, another assistant city attorney. “And I think it’s great that someone like Muncy can come up through the ranks and be city attorney. I think that’s going to help our office.”

Muncy joined the city attorney’s office in 1969, when it was headed by Alex Bick-ley. She worked for him until he left in 1976 to run the Dallas Citizens Council. For the last five years, she was Lee Holt’s first assistant. Now, she and her 50 at-torneys will handle all the city’s legal work, at a time when that is no easy job. They will write their own legislative bills, from 30 to 40 each session.

They will also continue an ongoing project: the rewriting of the three-volume city code so that the public can understand it, taking out all the heretofores, towits and hereafters. (Muncy has done about 15 chapters so far, one or two taking almost a year.) And, of course, the office will be working closely with the city council.

As Dallas has grown, so have the duties of the city attorney’s office. The attorneys have, by necessity, become specialized. Some work at D/FW airport, others spend most of their time at the police station. One works in the city tax department; one does zoning. Another specialty is employee relations. While one attorney is lobbying the Legislature for money to repair Dallas streets, a second is fretting over a contract with the Republicans, who are bringing their national convention to Dallas. How many phones will be installed, and who’s going to pay for them? Where will the buses be parked? Where will the press be installed? Will the convention center be heated on weekends in February?

WHEN ANALESLIE Muncy was still a child, her father, Charles Unfried, took her up in an airplane, flew her all over the country and said, “Analeslie, you can be whatever you want to be and do whatever you want to do.” He wasn’t exactly correct. What Analeslie wanted to be was an opera singer, to sing Il Trovatore like Janet Baker at the Met. She had the voice, but she couldn’t train it, and Analeslie finally gave up that notion after seven years with some of the best voice teachers available.

So, what to do? She had degrees in music and economics. She was happily married to Michael Muncy. But she had no profession. So Analeslie decided to go to law school at the University of Texas at Austin. During her second year, she became pregnant and just went to class, then came home and propped her feet. But she was determined to get that degree.

It would mean that she had a profession and would never have to be beholden to anyone. Even though she had two degrees and all that voice training, she says, “I started thinking about what I was going to do. If 1 had any drive at all, it was that I was going to have a profession.”

She was among 10 women in a class of 500 law-school graduates -women in law was still a relatively new concept in Texas. One job interview with a Dallas law firm was to replace a wheelchair-ridden researcher who was leaving. Her potential employer was blunt about her future.

“Now, if you come to work for us, don’t ever expect to do anything more than research.” It was perfectly clear: The firm was going to hire either a cripple or a woman to do its research.

Muncy, then 29, passed up that deal and got her first law job in Dallas’ municipal court, prosecuting those accused of indecent exposure and defending the city against other types perhaps more emotionally disturbed, who claimed to have fallen into open manholes. “Prosecuting in municipal court is a good experience for new lawyers,” she says, “but you can’t stay there forever. You get bored. We use it as our pool for filling other jobs in the office.”

There will be no boredom now. The city demands a lot for the $72,000 a year that it pays its city attorney. It’s not exactly an 8-to-5 job. Muncy gets home about 6:30, but works most nights and on weekends. “She gets up very early. She has a lot of energy,” says husband Mike. Taking the job was kind of inevitable. “She informed me when we were married that she wanted to work. I didn’t object so long as we could take care of our family. We’re very family oriented,” he says.

Though his wife’s schedule doesn’t bend, Mike Muncy’s does. He quit a college teaching job two years ago to work on his dissertation (he has a master’s degree in American studies) and ended up adding a room onto the house. It ought to be finished in about six months. “Right now, he’s running the kids around, and it’s gotten to be such a comfortable situation that we aren’t looking for changes,” says his wife. “I don’t worry about the kids or what’s going on at home because I know Mike’s taking care of things. 1 guess he likes what he’s doing or he’d be doing something else.” Mike Muncy also writes at home.

Analeslie is one of those women who can put together an electronic doorbell kit with a thousand pieces and rig it to play The Eyes of Texas when company comes. She fenced during her college days, and she can sew and cook. She paints portraits or walls; weekends are for painting the outside of her Preston Hollow house. She can get down on her hands and knees in an English abbey and do a brass rubbing of some saint’s tomb for six hours and swear she’s having a good time.

She can drink beer in the middle of summer. She can fish. There is one thing, though, she can’t do. She can take a fish off the hook, but she can’t clean it.

Their children, Megan, 7, and Mitch, 13, get culture at home. They listen to good music, especially Bach, Mitch’s favorite composer.

Analeslie and Mike married in 1969 at UT’s Catholic student center chapel. It was a small wedding-just family and a few friends. They had a deal: They would put each other through school. She was about to begin law school and he wanted to go to the University of Dallas.

They had met years earlier at a summer camp near Fort Worth. Analeslie was, by that time, a veteran Camp Fire girl and camp counselor. Mike dropped by one day to visit another friend.

She grew up in Fort Worth; her parents, Charles and Louise Unfried, still live in the Medfort Court House near TCU. He’s president and general manager of Fort Worth’s Better Business Bureau. Mrs. Unfried is a retired school teacher. Their daughter’s room, they say, was loaded with horse trappings. “We called her a horse idiot,” Unfried says. “She was a very confident child.” There was an old man who ran a stable about a mile from her house. Analeslie got up early in the summer to go down and watch him train his horses. He taught her to ride, train and show horses.

One day a boy phoned the house to see if she wanted to go to the movies with him. She said, “Well, there’s a horse show tonight at the Horseshoe Club. Wanna go to that?” He said, “No.” Then she said, “See you later.”

The bug to sing opera came later, during her sophomore year at college. She had been taking voice lessons since high school. But she went on to study voice in New York and then at the Royal Academy of Music in London, where she worked in the marketing division at Nestlé to pay expenses. “In voice, first you have to have the voice and then you have to have the technique. You can have the greatest voice in the world, but if you don’t know how to use it, you won’t go anywhere. 1 got to a level where 1 didn’t improve and I wasn’t really working at it. By that time I was 26 and 1 decided to quit because I didn’t want to be a hanger-on.” She still sings, but mainly at church.

“I suppose, if I had my way, I’d still bean opera singer. But that’s okay. I have alot of fun at what 1 do.”

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Hockey

What We Saw, What It Felt Like: Stars-Golden Knights, Game 4

The series is back on.

By Sean Shapiro and David Castillo

Local News

Leading Off (4/30/24)

Partly sunny today, with a high of 85 and chances of justice

By Tim Rogers

Local News

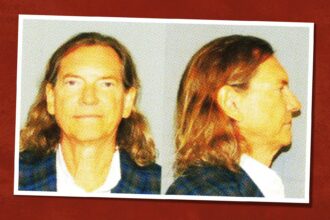

Bill Hutchinson Pleads Guilty to Misdemeanor Sex Crime

The Dallas real estate operator and erstwhile reality TV star will serve time under home confinement and have to register as a sex offender.

By Tim Rogers