Thousands of people strain in their seats as the strapping, raven-haired preacher crawls on his hands and knees at the edge of the stage. While he gropes among potted plants in the orchestra pit, his soulful eyes and soft voice exhort his followers: “Do you want to know what deliverance is? Do you want to know what true deliverance is?”

Then, after fumbling with a pot of poin-settias, he produces the crucial evidence-a large weed-and waves it at the TV camera. His voice rises slowly: “Deliverance is getting the weeds out of your garden! There are weeds all over your garden! And my people, there are demons all over this world! There are demons all over us! And if you don’t believe in demons, they’re all over you! If you don’t even want to talk about demons, people, they’re hanging off your front and back!”

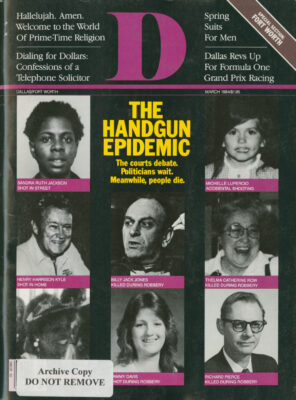

Hallelujah. Amen. Welcome to the world of prime-time religion.

Religious TV programming has increased some 30 percent during the past year, with annual expenditures now amounting to $1 billion a year. Inspirational programs air every morning on Dallas’ Christian-backed Channel 39. Home-based evangelists preach daily from an electronic pulpit. Local churches and synagogues feed a wealth of spiritual programming to Warner Amex’s Interfeith Access channel. There are biblical cartoons, a Christian soap opera, news shows, talk shows and the ever-present variety hours. The Good Word has never been spread across a larger or broader base.

The question of whether television has helped or hurt religion sparks debate among believers and non-believers alike. Some people see the plethora of religious programs as a natural extension of our increasingly oral culture. Dr. Walker Railey of the First United Methodist Church says, “It stands to reason that religion would be [on TV]. Practically every facet of life-from space to rock music-is seeing an increasing use of TV.”

But if that were the whole story, there would be little debate. As Railey points out, there is as much diversity in religious programming today as there is in secular TV and a similar ratio of genius to junk. The cause for concern lies not in the use of television itself, but in its potential for misuse-as a vehicle for religious hucksters, as a mouthpiece for ideology, as a stage for a show-biz style of worship. Some opponents wag a finger at blatant appeals for funds and a lack of accountability to donors. Liberals are often offended by the evangelists’ conservative, authoritative, narrow tone. Others are concerned that viewers who respond to the preaching are left with an impersonal faith.

TV preachers believe that Jesus’ charge to Christians is to spread the Gospel, and that means using the most effective tools around. Most media ministers say that they have answered a clarion call to preach-to help the hurting, to save lost souls. They argue that asking for money on TV is no different from passing the collection plate. Fair or foul?

CHRISTIAN broadcasting was born during the early Fifties, when evangelists such as Oral Roberts, Rex Humbard and Percy Crawford began preaching their fiery faith on the air. At the same time, some farsighted congregations began to broadcast their Sunday morning worship services (the First United Methodist Church of Dallas was one of the first). But it wasn’t until 1960 that a Yale Law School graduate-turned-minister, Pat Robertson (now host of the popular 700 Club), established an independent Christian TV station in Portsmouth, Virginia. Robertson is credited with paving the way for the production and syndication of Christian programs and for introducing organized fund-raising on the air.

Religious television grew steadily through the Fifties and Sixties and virtually exploded during the mid-Seventies. Then, during the late Seventies and the early Eighties, there was a general leveling-off. Today, some areas of production are experiencing growth; some, decline.

With the advent of cable TV, small religious groups and armchair evangelists can enter the field at a minimal cost, which has led to the current glut of programs on the air. Meanwhile, big-name, old-time preachers (Oral Roberts and Rex Humbard especially) have lost a substantial share of their audiences. Rice University sociologist William Martin, who has built a career studying the electronic church, attributes these losses more to shifts in audience allegiances rather than to a general drop-off of viewers.

Martin was one of the first people to assess the size of the religious viewing audience, and he publicly blasted national evangelists like Roberts for exaggerating the numbers in their video flocks. Martin estimates that the total number of people who watch syndicated religious television at least occasionally is somewhere between 20 and 25 million. The National Religious Broadcasters (NRB), citing a study soon to be released by Gallup Polls and Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School of Communications, sets the figure at closer to 50 million.

Religious programs come into our living rooms by several different routes. Some, such as James Robison’s weekly show on Sunday mornings, are carried by major networks-in this case, ABC’s local affiliate, WFAA. The big-boy networks tend to relegate religion to Sunday time slots-a fact that sticks in some people’s craws. Says Robert Tilton, who beams his broadcasts from the beacon Word of Faith Outreach Center complex on Interstate 35, “The prime-time slots are totally dominated by the secular humanists [a catchall phrase used often by born-again Christians to refer to people who make decisions independent of God].” TV stations tend to make decisions based on audience share, and Robison’s show, for example, pulls a one share-roughly 42,000 viewers. In TV terms, that’s a pretty meager draw.

To short-circuit network scheduling negotiations, many Christian producers have built their own stations. Currently, about 79 are operating with either an all-religious or a partly religious format. The NRB estimates that, on the average, at least one new station is added each month. Some stations are linked to a religious network such as Pat Robertson’s Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN); others spring from systems operated by mainline churches. Southern Baptists have recently launched an ambitious network headquartered in Fort Worth. The American Christian Television System (ACTS) plans to broadcast on 10 to 15 stations and on 1,000 cable systems within a year.

But not all Christian-owned stations showcase religion non-stop. For example, Channel 39, the local CBN station, fills out its schedule with “wholesome family entertainment’-mostly reruns that hark back to simpler times: My Three Sons, Green Acres, Father Knows Best.

With the invention of the satellite, religious TV was ushered into the big time. Instead of going through the costly process of duplicating hundreds of video cassettes and distributing them to local stations, a producer now can simply beam his broadcast to anyone who has the necessary receiving equipment: namely, a transponder or “down-link dish.” Early pioneers like Robertson and Jim Bakker, whose PTL network (Praise The Lord or People That Love-take your pick) has grown tremendously during the past few years, had the foresight to get in on the technology when it was relatively cheap.

One Dallas group, the Word of Faith, has seized the satellite potential. Each Sunday, Pastor Robert Tilton, a former Richardson homebuilder-turned-Christian preacher, speaks live to some 4,500 people-60 percent of whom, he says, come to him directly or indirectly from his exposure on radio and TV. Four nights a month, the Word of Faith beams closed-circuit seminars to some 1,100 churches nationwide. The Tiltons’ periodic Bible studies are carried by 700 far-flung Bible groups, and Tilton estimates that a quarter of a million people watch his daily mass-market show, Success in Life.

Says Robison’s executive producer, Paul Cole, “You have to credit Bob Tilton for having the moxie to put that enormous satellite network in place. Everybody said he was crazy.”

The growth of cable TV has contributed to the escalation of religious TV, especially at a grass-roots level. Warner Amex has a full-time employee who coordinates religious groups wanting to use the free air time provided on Interfaith Access Channel 12. Outreach specialist Linda Haycook will lend you video equipment, show you how to use it, give you tips on how to stage a production and schedule you into a suitable time slot. The only hitch is that you can’t solicit contributions on the air. Because of that, most independent evangelists take their messages elsewhere.

It’s easy to identify a religious show when you flip the channels and land on a brimstone baritone shaking his fist at the sky. But some formats are more subtle. Recent years have seen an increasing secularization aimed at attracting non-believers. With techniques that range from newscasting and animation to drama and slapstick, the new buzzword is “soft sell.” One of the most intriguing of the new-format shows is CBN’s Another Life, a soap opera in which characters grapple with the gamut of human situations ranging from premarital sex to abortion and divorce. Christian ethics and the Divine Spirit always prevail.

The most popular format, though-and the one with the most staying power, according to NRB’s Dr. Ben Armstrong-is the talk show. Borrowing a bit from Carson and Donahue, a congenial host and his sidekick give inspirational straight talk about everything from deficit spending to how to tell if you’ve truly been saved. There are testimonial clips, healing sessions and visits from guests who have overcome travails ranging from drug addiction to lust in their hearts.

Even a skeptic could get hooked on the breezy talk-show style, but the cloying Christian variety shows are harder to swallow. The hosts of these programs (which seem to run for hours on end) tend to look like holdovers from The Lawrence Welk Show or, as one observer put it, “like they’ve been embalmed.” A ministrative emcee, aided by his demure wife, alternates his own crooning with the crooning of others, occasionally taking time out for a chat about “how tough preaching is” or a visit from a cowboy minister who does rope tricks. About every four minutes, the host gazes into the camera with an earnest appeal for “the largest love gift you can send.” Invariably, the camera zooms in on hands clenched in a desperation belied by his diamond rings and her $250 fingernails.

The talk shows and variety shows are dominated by conservative, often charismatic “born-again” Christians. Partly in response to that, mainline denominations -Catholics, Methodists, Baptists, Jews-have begun to fill the airwaves with their own shows. ACTS is in the process of producing some two dozen new shows ranging from musical specials to a “Sesame Street for moral truths.” Los Angeles-based Jewish Television Network (JTN) broadcasts Yiddish music, sermons from rabbis and other programs aimed at attracting Jews who aren’t members of local synagogues. Unlike the newer entries in electronic religion, the Roman Catholic Church can look back on a television tradition dating to Bishop Fulton Sheen, whose TV show aired during the Fifties in a prime-time slot opposite Milton Berle. Today, a national Catholic network presents interview programs, religious dramas and P.M. Magazine-type shows picked up in Dallas on a dish atop the Catholic Diocese and distributed on local channels. The intrachurch linkup also provides communication among dioceses nationwide.

The mainline shows differ from the evangelists’ broadcasts in several ways. They place less emphasis on preaching and more on religion in daily life. One reason is that the high liturgical churches don’t put a premium on preaching; ritual sacraments form the centerpiece of their services. It is doubtful that a Catholic priest would or could compete with a practiced orator like Jerry Falwell, whose silver tongue is his stock in trade. And the goal of the denominational churches is not to offer TV as a substitute religion but to lure strayed souls back to the pews. Nor do the mainliners solicit seed money on the air. Says Railey, “Some of the preachers sound like mercenaries with their constant appeals for funds. After a while, the hard sell begins to obscure the message.”

Even though mainline ministers may have been critical of the evangelists’ inroads on television, they also admit their effectiveness. For years, the major denominations seemed content with an occasional Sunday broadcast of their church services. Says Steve Landregan, Catholic deacon and director of the Archbishop Sheen Center for Communication, “The camera in the choir loft is not an adequate use of the medium.”

Satellite and cable technologies have allowed the TV ministries to air, but it’s the computer that enables them to thrive. The more successful ministries incorporate sophisticated direct-mail operations that peg potential donors and plug into them for dear life. Typically, during a preacher’s performance, a toll-free telephone number flashes across the bottom of the screen. You may or may not be asked for money directly, but any response-for prayer, counseling, a book order or the purchase of a holy trinket-will land you on the mailing list. Once you get on it, you’ll be deluged with literature until you either give more or ask to have your name removed.

Kenneth Copeland Ministries (off Interstate 30, just east of Fort Worth) is one of the slickest operations around. Copeland, a disciple of Oral Roberts and a witty, able entertainer, has hired an experienced businessman to systemize orders and contributions. In a lush, dignified setting that would put an IBM office to shame, 200 employees see to it that none of the 2,500-plus pieces of daily mail falls through the cracks. They count money; code, computerize and answer mail; respond to the counselor phones; fill orders for books and tapes; and (with the aid of a mechanized envelope stuffer) prepare outgoing mail. When touring the Copeland organization, it’s easy to forget that the business is religion-until you come upon an unmistakable sign: a giant Wang computer imprinted with large letters that spell “Jesus Is Lord.”

Why have millions of TV viewers embraced the electronic church? Some say that organized religion is responsible. Even mainline preachers admit that their churches have failed people in several crucial respects. “The evangelists have appealed to a deep human-felt need in people,” Railey says. “The prime-time TV specials look like life, and a typical Sunday church service looks like death.” Pastors point to a reticence and a lack of courage in the pulpit. Railey says, “Whatever else you say about them, the evangelical preachers preach with authority. People respond to that. In the Eighties, we need to see more articulate people willing to take a stand.”

Dr. Tom Moore, a former Catholic monk and professor of religion at SMU who is now a psychotherapist, views the TV worshipper from the perspective of both religion and psychology: “People look to someone to tell them what to believe.. .and the fact that these preachers are coming to them on television gives them increased fascination and authority. What is televised often seems more real than what goes on in real life.”

Evangelists agree that their message is absorbed by people who have lost faith in their world. Says Tilton, “You want to know why our churches are so powerful? Because we have the absolute answer to what people need.”

Tilton preaches a gospel of prosperity- a “your-dream-can-come-true” prophecy of personal success. His message is variously described in his literature as a “prospectus,” a “spiritual diet and exercise program” and “success steps.”

But Tilton is not the first to dangle success as the carrot for spiritual growth. Oral Roberts pioneered the technique, and Kenneth Copeland has followed a similar suit. However sincere they may be, these preachers imply that a few dollars’ worth of seed faith and a pamphlet will provide everlasting material comfort. Martin says, “[That type of teaching] has, at the very least, the potential to be self-serving. In some parts of the world, it would be ludicrous if not downright cruel.” Railey agrees: “The TV preachers make salvation look great. In fact, they make it look downright luxurious. It becomes a vicarious experience for people [who are] watching all that joy and sparkle from Lazy Boy loungers in their own drab living rooms.”

Another criticism is that the message of prime-time preachers is oversimplified. Says Landregan, “Religion is more than receiving the Good Word. Televised Christianity is a billboard message; it’s incomplete. It’s like a three-legged dog: It’s still a dog, but it limps along.” Moore agrees: “The message is both intellectually and emotionally simplistic. Religion is very subtle. The Catholic Church is fond of following the phrase festina lente-make haste slowly. Electronic preachers simply make haste.”

If the message is suspect, the methods are even more so. Nothing (except appeals for money) raises ire in a critic more than the evangelists’ tendency to claim that “God told me to…” (“God told me to buy 2,000 acres and build the biggest revival camp the world has ever seen.” “God told me to tell you that this one broadcast tonight cost me $2 million.”)

“What it amounts to is canonizing your wish-dreams,” Landregan says. “It cuts off all argument because you’re, in effect, arguing with God.” Railey agrees: “It’s always amazed me that God speaks to the TV evangelists so much more regularly than the rest of us.”

THE AUTHORITY that evangelists project is unmistakable. Some people also see that power as a dangerous enemy of the religious pluralism on which our country was founded. Some think that the narrow view-the perspective that, “You’re either with us or you’re damned to hell”-is frightening. Says Milton Tobian, Southwest regional director of the American Jewish Committee, “To practice anti-pluralism is the ultimate affront to the American way. Tolerance is the glue that holds us together.”

Prime-time preachers do more than glorify God; they glorify the American way- their American way. And if that way is intolerant or anti-pluralist, so be it. Evangelists have never shied away from touchy political themes, preferring instead to use God’s pulpit as a forum for moral leadership.

The kingpin of political preaching is, of course, Jerry Falwell, whose dual role as minister and right-wing political activist is often obscured. Until recently, James Rob-ison (see sidebar, page 77) seemed to be following Falwell’s lead. Robison’s weekly show on WFAA-TV came under fire several years ago from both the station’s management and the FCC for its airing of disparaging remarks about homosexuals. Gay activist Don Baker recalls: “First, [Robison] started talking about the gay issue, giving his biblical perspective, and that was fine. But when he quoted an article in The National Enquirer saying that child molestation is commonplace among gays, we got up in arms. After we complained to the station and they took the show off the air, Robison tried to say that we were saying that he should be restricted in his right to preach. We never questioned that right.”

Robison waged a legal battle led by famed defense attorney Richard “Racehorse” Haynes against the FCC after it ruled that in canceling the show, WFAA was exercising editorial discretion rather than censorship. Eventually, the matter was settled out of court, and the weekly program was put back on the air.

Anti-gay, anti-abortion, anti-ERA, anti-Communist themes resound often through the sermons of TV evangelists. Mainline preachers address moral issues that pertain to Christianity in daily life as well, but some draw the line at lectures on national economics or other overtly political themes couched in the guise of religion. Says Tobian, “I’ve read both the Old Testament and the New Testament from cover to cover, and I’ve yet to see mention of the gross national product. I have a problem with preachers putting God’s imprimatur on one economic path over another.”

The most obvious shortcoming of the electronic church may be that it emanates from a mechanized box. The image of a sick or dying soul staggering over to lay hands on a TV set is a pitiful one, yet many people do just that. And surely, many people are disillusioned. Even those who are pleased with the impact that TV religion has had on their lives are left with an isolated faith. “TV doesn’t require involvement,” Landregan says. “It fails to provide a personal relationship. When people are hurting, they need a human touch. God reaches us through real-live human beings.”

No matter what twists and turns a debate on religious TV takes, it ultimately centers on the subject of money. Large ministries like Copeland’s and Robison’s require huge sums-estimated at $1.5 to $3 million per month-to keep them afloat. In addition to taping TV shows, producing backup materials and carrying the overhead necessary to tend their flocks, both preachers mount ambitious traveling crusades all over the world. According to Railey, “What happens is- and I see this in the denominational churches as well-you reach a level in your ministry at which maintaining the institution su-percedes its original intent.”

In a church, fund-raising efforts can be carried out behind the scenes. With occasional exceptions, the preacher doesn’t dirty his sermon with long diatribes on how poor the congregation is. A quiet ceremony-the passing of the offering plate-does the trick. Not so on TV, where sometimes as much as half of the purchased air time is spent rattling the tin cup. Even if you accept the notion that raising funds for religious purposes is as old and honored as the Bible, after a while the incessant hawking gets in the way.

And the preacher who freely and flagrantly flashes his own prosperity only adds fuel to the fire. Even renowned evangelist Billy Graham has gone on record deploring “the excessive pride, worldly methods and infatuation with success of many TV preachers.” In an article in Newsweek. Graham is quoted as saying, “You don’t hear much [from them] about the hungry masses, the inner-city ghettos or the nuclear arms race.”

Copeland has been criticized for his penchant for the “trappings of success”- including a Mercedes, a Jaguar, two corporate jets and an expensive lakefront home. Copeland, who refused to be interviewed for this article because he was, according to a start member, “spending the month of January in prayer,” has consistently refused to reveal the financial details of his organization, including ambitious plans to build a revival headquarters on nearby Eagle Mountain Lake. A spokesman, associate minister Barry Tubbs, claimed not even to know the construction budget for a three-story structure currently being built there. Unlike Rob-ison’s, neither Copeland’s nor Tilton’s ministry is a member of the national Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability, an organization defined by its director as both a watchdog and the genre’s Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval.

ARGUMENTS ASIDE, there is no denying that television has had a profound impacton religion-an impact that is bound to increase as time and technology carry us further into the information age. Whether theinroads amount to a gospel glut or the mostmiraculous amplification of The Word sincethe New Testament depends on your spiritual vantage point. But as long as those cardsand letters keep coming, the prime-timereligion show will go on.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Hockey

What We Saw, What It Felt Like: Stars-Golden Knights, Game 4

The series is back on.

By Sean Shapiro and David Castillo

Local News

Leading Off (4/30/24)

Partly sunny today, with a high of 85 and chances of justice

By Tim Rogers

Local News

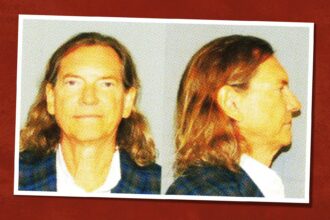

Bill Hutchinson Pleads Guilty to Misdemeanor Sex Crime

The Dallas real estate operator and erstwhile reality TV star will serve time under home confinement and have to register as a sex offender.

By Tim Rogers