At Union Square and Madison Square Park, banners with In-N-Out’s yellow boomerang logo blanketed vacant storefronts, proclaiming the message: “Coming summer 2010.” Employees of the California-based fast-food chain, clad in its iconic paper hats and red aprons, passed out flyers. The news lit up Facebook and Twitter. Food blogs reported that the sloppy, juicy In-N-Out burger would, at long last, make the journey to the East Coast—a dream so desperately desired that no one stopped to take note of the date: April 1. By late afternoon, the April Fool’s Day prank by the people behind the website CollegeHumor.com had spread so far and wide that the publicity-shy In-N-Out took the rare step of issuing a statement declaring that the chain was not opening in Manhattan.

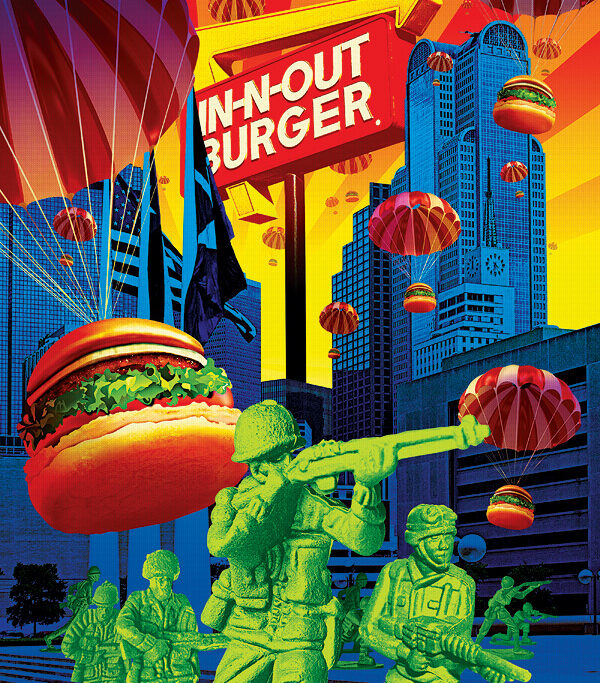

Later this spring—the company won’t get any more precise than that—In-N-Out fever will spread to North Texas. Count on hordes of In-N-Out addicts and curious burger aficionados to descend on the new restaurants (see map, page 61). TV helicopters will whirl overhead. Drive-through lines will snake through parking lots. Fans will camp overnight and wait in hours-long lines. An In-N-Out “all star” team will fly in to manage the chaos.

Do the hamburgers warrant all that fuss? Some certainly would say they do. But the cult of In-N-Out is really about more than the food. To understand why people get so worked up over, say, an Animal Style and well-done fries, you have to understand how America’s most secretive, privately held fast-food chain does business.

For six years, I’ve covered the restaurant industry in Southern California, the epicenter of America’s most enterprising restaurant category, fast food. My coverage has taken me behind the scenes of some of the biggest players in the $191 billion industry. I’ve toured the ketchup-making plant for Arby’s, Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen, and Church’s Chicken. I’ve trudged through lettuce fields that supply Subway, Burger King, and Jack in the Box. I’ve watched dough baked for Big Mac buns and Egg McMuffins. I’ve stood on grill lines at Wendy’s, McDonald’s, and Five Guys Burger and Fries. But by far the most privileged, carefully controlled behind-the-scenes access I’ve ever gotten has come from In-N-Out Burger.

In 2006, I became the first reporter ever to tour In-N-Out’s California meat-processing plant and distribution center. And, just a few months ago, I was invited to see one of the Los Angeles-area bakeries that supplies the chain’s old-fashioned sponge-dough buns. The plant is the key to In-N-Out’s quality control. Executive Mark Taylor told me that the chain limits new stores (until now) to within 500 miles of the facility to maintain freshness. While other fast-food chains have turned to frozen patties, preservative-packed buns, vacuum-sealed produce, microwave ovens, and heat lamps over the years, In-N-Out does it the same way it always has, since 1948. Nothing is frozen. Everything is cooked to order.

At the distribution plant, I walked through a cold storage warehouse stacked with bags of fresh potatoes and onions, crates of lettuce heads, cartons of vine-ripened tomatoes, and blocks of sliced American cheese. The highlight of the tightly managed tour—where photos were strictly prohibited—was the beef-processing plant. From behind a window, I watched butchers in blood-splattered white coats hand-bone 140-pound prime chucks hanging from stainless steel hooks. The process was grueling and the workers meticulous. After the butchering, a proprietary blend of meat went through a double-grind system. The end result: a perfectly textured 2-ounce 100 percent pure beef patty ready for grilling. The burgers are boxed and shipped nightly to restaurants. The entire journey—from cattle farm to between two buns—generally takes less than five days.

During the tour, I also got to observe the cook line in the flagship restaurant on the In-N-Out campus in Baldwin Park. Inside the kitchen, clean-cut, cheerful workers moved with great purpose. Fries and patties were cooked to order. Four-inch-wide sponge-dough buns, supplied by two bakeries, one being the same baker the company has used for 45 years, were toasted on the grill and topped with the chain’s secret sauce, which is made from a recipe known to only a handful of people. Onions were chopped and ringed to order. Lettuce was hand-leafed. Out front, workers scrupulously wiped down tables and swept floors.

Near the end of the tour, Taylor and I ordered lunch. I was impressed by his off-menu order: double meat, medium rare, with mustard and spread only. At the time, I thought I possessed an above-average familiarity with In-N-Out’s famed list of secret menu items. But I never would have suspected that anyone could order a fast-food burger the same way one might order a steak in a white-tablecloth restaurant. Taylor’s center-red burger was the ultimate demonstration of In-N-Out’s commitment to fresh ingredients.

“No one else can do that,” said Taylor, who is now the chief operating officer of the company.

Fourteen hundred miles away, that promise will be put to the test in North Texas. Despite having a legion of cravers coast to coast, In-N-Out has steadfastly remained a regional chain concentrated in four Western states: California, Nevada, Arizona, and Utah. The 500-mile limit from the distribution hub kept expansion in check. Now, for the first time, the chain is making patties somewhere else. Stores will pop up in Allen, Frisco, Garland, Dallas, and Fort Worth. Either Allen or Frisco will claim bragging rights as the first Texas In-N-Out.

To re-create a phenomenon that for six decades has been confined to the West Coast, In-N-Out will build a second distribution hub in Texas. The company has not disclosed where the permanent facility will be, but right now the chain is leasing a temporary warehouse in West Dallas to support its initial Texas growth. The 60,000-square-foot facility will house a beef-processing plant and supply warehouse. Nabbing a partnership of a lifetime is Hereford-based Caviness Beef Packers. The family-run cattle operation, located in the Panhandle for more than 45 years, will deliver beef to the Dallas In-N-Out plant. From there, it will go through the same butchering process I saw in Baldwin Park.

As In-N-Out enters a fifth state, rumors about a nationwide expansion have accelerated. The chain’s California hub supports 251 restaurants. Could a new Dallas facility eventually support the same number of In-N-Out restaurants in, say, Tulsa, Santa Fe, and Kansas City? For now, the company is mum.

“We are very enthusiastic about our expansion into Texas,” says Carl Van Fleet, In-N-Out’s vice president of planning and development. “At this time, we are focusing specifically on the Dallas-Fort Worth market, as there are many exciting opportunities there.”

Van Fleet says opening new restaurants in North Texas will “keep us plenty busy for the next several years.” However, he allows that the distribution hub could eventually support locations in other Texas markets, such as Houston, Austin, and San Antonio. With the much-vaunted Fatburger on its way to Dallas and with Carl’s Jr. having recently opened 10 restaurants around Dallas (and considering moving its corporate headquarters here), the front of the war between the fast-food burgers has suddenly moved to North Texas. On one side, the huge corporations. On the other, the quirky In-N-Out operation that still doesn’t have a PR department.

it all began in 1947, when Harry Snyder, the son of Dutch immigrants, met his wife, Esther Johnson. He sold baked goods to a Seattle restaurant where she worked as the day manager. They fell in love, married, and settled in Baldwin Park, a former cattle grazing community 20 miles east of Los Angeles. The Snyders opened In-N-Out Burger across the street from their house in 1948, the same year the McDonald brothers launched a burger shack in Southern California. Three years earlier, the forerunner of the Carl’s Jr. chain opened 30 miles away in Anaheim.

A cunning entrepreneur by the name of Ray Kroc would eventually take over McDonald’s and turn it into the world’s largest burger chain, with more than 32,000 U.S. restaurants worldwide. Over the following two decades, the fast-food industry was born, with Burger King, Jack in the Box, Wendy’s, and Wienerschnitzel getting into the game. Most of the big players became Wall Street darlings and began franchising relentlessly—but not In-N-Out.

From the beginning, the Snyders employed a simple strategy: serve a freshly made burger in a sparkling clean, customer-friendly environment. And, above all, keep it a family affair. Esther managed the books, while Harry, a workaholic and neat freak, ran the day-to-day operations of a restaurant that featured a “two-way speaker” drive-through lane, an industry innovation that was the first of its kind in California and likely the nation.