Not so long ago, Dak Prescott might have come into the NFL as a tailback. His counterpart on the Arizona Cardinals, Kyler Murray, would have profiled as a tailback. Patrick Mahomes? A wide receiver, perhaps.

Such was life for Black quarterbacks hoping for a shot in the professional ranks. The mandate was simple: change positions or wash out. Because, for much of its history, professional football viewed Black men as too stupid or lazy to lead their own team.

It took decades of hard-won progress to create the world they play in today, where all three are signed to some of the most lucrative contracts in league history as the quarterbacks of their respective franchises. That journey, along with men who shaped it, is chronicled in Rise of the Black Quarterback: What It Means for America, the excellent new book by Jason Reid, senior writer for ESPN’s Andscape.

I spoke with Reid last week about what he learned most during the project, Prescott’s role as a superstar Black quarterback for the NFL’s most popular franchise, Murray’s significance as a Texas high school legend (and that infamous clause), a what-if involving the Cowboys and Warren Moon, and more.

First off, this is an essential book, and I’m so glad you wrote it. I imagine the research confirmed a fair number of things you long suspected to be true. But what surprised you most doing this project?

Even though I tried to act like I was coming to this from a totally fresh perspective, you bring your thoughts and ideas, and I thought I understood the racism these guys went through—the pioneers. Hearing the actual anecdotes, though, of the guys who gave me time—Marlin Briscoe (who recently passed away), Warren Moon, Doug Williams, James Harris—hearing the racism they actually faced and the specific anecdotes, it was eye-opening. Again, I knew, generally speaking, these guys went through racism. Experienced significant racism as they tried to become established at that position in a league that didn’t want them. but it was eye-opening, I’m not going to lie.

Is there a particular one that, even now, is burned in your brain the most?

The Marlin Briscoe story. For my first interview with Marlin, we sat down over lunch. He’s telling me the story, and I’ve researched the story before I sat down with him, but to actually hear the details. It’s 1968, he’s a star quarterback at the University of Nebraska-Omaha. He doesn’t have the typical size you wanted at the position then, but he was successful. But in 1968, Black men were not being drafted into the NFL or the old AFL to play quarterback. The Broncos take him intending for him to switch to cornerback. He tells them he won’t sign unless he gets a tryout to play quarterback.

The process was rigged—he was never going to get the job—but they threw him in there after the starter gets hurt, they’re having a bad season, and no one else was effective. And to the shock of management and the coaches, the guy performs really well. He set the Broncos rookie record with 14 touchdown passes. He finishes high in the AFL Rookie of the Year voting. He succeeds.

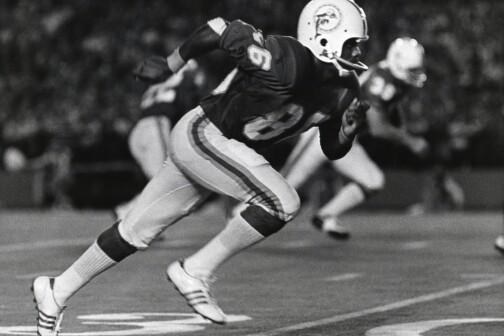

He goes home to Omaha to work on his degree, and he gets a call from a friend saying, “Hey, they’re having quarterback meetings here.” He’s like, ‘Well that’s impossible. I’m the quarterback.” Finds out, no, he’s not. It was one thing for them to have a Black quarterback when the starter was hurt and they were having a horrible season. But they were not going to move forward with a Black quarterback. He winds up reinventing himself as a top wide receiver, has a great year with the Buffalo Bills, wins a couple Super Bowls with the Miami Dolphins, but he never gets to play quarterback again.

Decades later, I’m sitting at a table in a restaurant talking to him about this, and he’s going through the details, I can just see the pain in his face as he’s recounting this to me. I asked him, how did you get over this? And he said to me—I’ll never forget it—he said, “You’re assuming I have.”

Wow.

And what struck me about this is I thought about myself. If I proved I could do something from a career standpoint simply because I’m Black, I don’t know how I would cope with that. There are tons of them. James Harris telling me about all the hate mail—he got so much hate mail his rookie year in training camp with the Bills that they couldn’t even bring all of it back to his room. Doug Williams, the racist shouts directed at him when he was a rookie with Tampa Bay. Warren Moon, his family didn’t even want to sit in the stands—they were sitting back in the family room. He’s succeeding as a quarterback for Houston, and these racist people are shouting right behind his wife and kids. Those specific anecdotes.

As a Dallasite who wasn’t alive during the height of the Landry years, perhaps the biggest thing I learned was John Wooten’s story. For those who don’t know, what was his impact on the Cowboys in the Tom Landry era, and how rare was it to have a Black man in some position of influence in personnel during those days?

Wooten will tell you that Tom Landry did a lot for his career. Tom Landry put John Wooten in position to where he could become a player personnel man, and you just didn’t see Black player personnel executives in the league. Tom Landry, Gil Brandt, Tex Schramm: from all the research I did, they valued John Wooten’s opinion. And John Wooten contributed greatly to the scouting of many players who helped that team basically make the playoffs forever.

Another interesting thing about him. John Wooten played under the legendary Paul Brown, and he also helped to move race relations in the NFL forward. Because one thing Paul Brown used to do is relay the plays to the quarterback and what he wanted executed. This was before the days of electronics and headsets. He did that by what he called his messenger guards—he would rotate these guards in and out, and these guards would bring messages to the quarterback. To have a Black messenger guard, that’s how much Paul Brown trusted John Wooten to do that. It says a lot about John Wooten, and it helped to move things forward because there was a perception of Black players in the NFL—not just Black quarterbacks—that they were stupid and lazy.

There was one key area where his voice wasn’t heard, though. In 1978, he pounded the table for the Cowboys to draft Warren Moon. And they weren’t the only team to pass on him—every single NFL team did that year. But it does speak to how pervasive the discrimination was, that even the team of the 1970s would not give Black quarterbacks an opportunity.

It was just a bridge too far. I had this scene in the book where he goes to scout Warren Moon, and back in those days it was just understood that if you were Black, you were not going to be drafted as a quarterback. You were not going to be permitted to play quarterback. You were going to be moved to another position. Wooten walked me through the meeting where he presented to Tom Landry and Gil Brandt and the other scouts and executives that, hey, this guy is going to be special. Wooten didn’t say who it was, but somebody in the room said, “Did you talk to him about moving positions?” And Wooten was adamant that, no, because Warren Moon is a quarterback. He is a quarterback.

Now I don’t know how that would have played deep in the heart of Texas in the late 1970s if Warren Moon had been drafted by the Cowboys. Obviously Tom Landry was a god at that point, and if he’d have wanted to do it, maybe he could have sold it. But it was not something anyone in that room thought made sense. Nothing against Warren Moon, but he’s Black. Like, Black guys don’t play quarterback in the NFL. In fact, the draft in which Wooten was standing on the table and arguing on behalf of the Cowboys doing this radical thing, that was the first draft in NFL history in which a Black quarterback was taken in the first round—Doug Williams by the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. This is no indictment of the Cowboys by any means because no other team in the NFL drafted Warren Moon. It wasn’t like the Cowboys were so, so awful that didn’t taken Warren Moon. As great as the Cowboys were at that point, as well-run as they were at that point, it would have taken the ability to look way, way into the future for them to have gone that route.

Now I don’t have my Cowboys almanac in front of me, but if memory serves, if they had taken Warren Moon in that draft, then you’re not transitioning from Staubach to Danny White. You’re transitioning, most likely, from Staubach to Warren Moon. And how different might Cowboys history have been then?

That is a fascinating hypothetical. And since then, a lot has changed. Down here, that starts with Dak Prescott. What does it mean for America’s Team to have a Black franchise quarterback?

I wrote about this back in 2016 and, literally, what this meant. You have to remember, this is a time when Donald Trump is President, NFL and NBA players are in [the throes of] the protest movement ignited by Colin Kaepernick—or reignited by Colin Kaepernick. Dak Prescott is not the first Cowboys Black quarterback; Quincy Carter [was].

But to have a superstar Black quarterback deep in the heart of Texas—you know, representation is important. Black kids in Texas had not see a superstar quarterback for America’s Team who was Black. When you talk about that, especially with what was going on in the country, it definitely makes you think about, OK, how do you reconcile this? One Black quarterback is taking all this heat nationally for shining a light on oppression and police brutality yet America’s Team has a Black quarterback. If nothing else, it’s got to be thought-provoking.

Right, and let’s take it a step further. If the Cowboys ever do break the Super Bowl on his watch, how huge would it be for a Black superstar quarterback to succeed where so many others failed?

It’s definitely going to be significant on so many levels. The Cowboys are America’s Team—I know a lot of teams hate that thing, but let’s face it: they are the most popular franchise. What that star means, what it represents. So, yeah, it would be very significant culturally. And I can guarantee you within Black America and Black culture, it would resonate across the country.

He’s succeeding as a quarterback for Houston, and these racist people are shouting right behind his wife and kids.

Jason Reid, author of “The Rise of the Black Quarterback”

We don’t get a lot of Dak in the book, but we do get a lot of Kyler Murray, who of course is from North Texas. I think you captured his importance so well: It’s not just that he’s on the shortlist for the greatest Texas high school football player ever, but that he did so as a short, Black quarterback who isn’t afraid to go off script—which not so long ago was an archetype that was really taboo.

Oh, a taboo archetype on steroids. One thing I wanted to do with this book—I didn’t want to just write about all the Black quarterbacks who ever played. I wanted to look at the pioneers, the guys on whose shoulders today’s players stand, but I also wanted to look at present quarterbacks because of what they represent in the evolution of the game. And never in NFL history would a 5-foot-9 Black quarterback be the No. 1 player picked in the draft. You just would never see it. So it shows the evolution of the game.

You mention the off-script thing. I remember I was having a conversation with Mike Shanahan, former Super Bowl-winning coach of the Denver Broncos, and he talked to me about quarterbacks are paid based on two things: what they do on third down and what they do off script. Because the way the game is now, you don’t have to be Lamar Jackson and be able to outrun fast defensive backs. But when that first, second, and third read is taken away, you have to be able to extend the drive in the pocket at the very least and make something happen. Kyler Murray, Patrick Mahomes, Russell Wilson—these guys all do things off script, off schedule, that are fabulous. That is part of the evolution of the game, without a doubt.

What did you make of the homework clause in his new contract?

Oh, my goodness. I was actually texting with Warren Moon about this. And I got what Warren was saying: this is horrible and immediately brings to mind the way things were in the past when we were just lazy and stupid. I don’t draw a straight line—or even a crooked line, for that matter—with the racism of the past and Kyler Murray’s contract. Now it does bring back memories of that, no doubt. But I look at this as more specific to Kyler Murray. Kyler had some quotes attributed to him where he talks about how he does his job but he’s not like a gym rat, so to speak. There are no sacred cows: no one’s redshirting here, everyone gets to be evaluated. So when people brought it up, yeah, that’s not the best thing to say.

Now, having said that, you don’t guarantee a guy $160 million for injuries and $105 million in signing—the second-biggest guarantee in the history of the NFL—if you are not all-in on him, don’t give him that type of money. If you’re going to give him that type of money, you don’t put an independent-study addendum in the contract saying we want you to study more. It was such a colossally stupid thing to do. And I also put it on Kyler Murray’s agent, who never should have let that kind of language in that contract.

I had another team’s executive tell me, “Look, they’re probably generally OK with his study habits. He is successful. But if you’re going to guarantee him the second-biggest guarantee ever, you probably want to prod him a little bit to do a little more. But here’s the thing: you don’t put it in the contract. That’s a private conversation.” So the Cardinals messed up, and they acknowledged as much by taking it out of the contract. But now the damage is done. The rest of his career, whenever he has a bad game, people are going to wonder if he studied this week.

Last one: we’ve seen a lot of progress for Black quarterbacks over the last 60 years. Where does there most need to be more progress going forward?

We saw recently in an article ranking quarterbacks that there was some coded language from anonymous defensive coordinators about Patrick Mahomes and Lamar Jackson. And Patrick Mahomes felt compelled to address it. What he said was, as Black quarterbacks, we have had to fight to get here. We’ve proven we should have been here all along. But even today, some of the criticism about us doesn’t sound like it sounds for some people who don’t look like us.

So, look, things have never been better for Black quarterbacks. They have the biggest contracts, they are the faces of their teams, they’re adored by fans, they have power that was considered unfathomable even 10 or 15 years ago. But progress is not perfection, and where we still need progress to be made is some of this coded language in how they’re described, if people want to use that, put their names to it.

Author