About two years ago, I was chatting with my old friend and former neighbor Steve Nash, then in his fourth year as director of the Nasher Sculpture Center. “What is it that you do all day?” I asked innocently. “Surely you can’t be dusting the tchotchkes from dawn till dusk. You must be planning shows. And raising money.” I continued: “But who would want to give money to a museum with someone else’s name on it?”

“Bingo!” he exclaimed. I could hear the frustration in his voice.

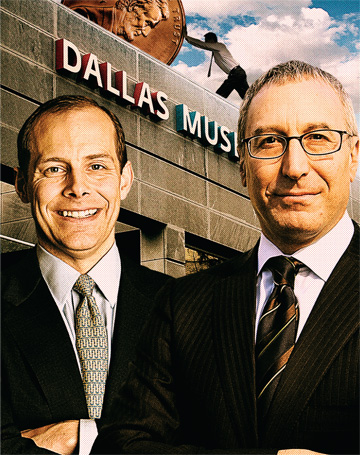

Nash announced his resignation as director two years ago, and Ray Nasher died shortly thereafter. One doesn’t suspect a cause-and-effect pattern, but it took the Nasher trustees two years to find and name Jeremy Strick as its new director. He arrived in March from the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles to take up the curatorial, dusting, and fundraising duties, the last of which are harder now than ever before. Eric Lee comes at the same time to the Kimbell Museum from Cincinnati. It also took the Kimbell trustees awhile to find the right person for the job. Museum directors are playing a game of musical chairs, but “hot seat” is a better phrase.

What kind of job will these men have? Who can possibly succeed, and by what means? Today’s director must serve many masters. Not just God and Mammon, if by God and Mammon one means High and Mighty Aesthetic Principles on the one hand, and the Forces of Crass Commercialism on the other. In the old days, museum guys had it good. It was always guys, of course. WASP aristocrats, well bred and well-heeled, they ran their museums for decades, with every curator the equivalent of an academic dean controlling a little fiefdom. Acquisitions came by hook or by crook, the public wandered in or not in a lackadaisical fashion, and aesthetes could stand or sit alone in front of their favorite works without being disturbed by anyone else, let alone busloads of gawking, screaming tourists.

Those days are gone forever. Now that Philippe De Montebello recently has stepped down from the Metropolitan Museum, we have only his plummy voice on countless Acoustiguides to remind us of the day of the patrician as director. Seymour Slive, great Dutch art historian and head of Harvard’s Fogg Museum, said that the best museum director would be Jesus Christ with a French wife. That was 25 years ago. Jesus wouldn’t be good enough today, although the French wife would still constitute an asset. The director’s job has altered because the museum itself has been transformed.

Ted Pillsbury, the long-time director of the Kimbell (from 1980 to 1998), has a French wife. Even he acknowledges the extent to which things have changed since he moved to North Texas three decades ago. “Directors are CEOs of billion-dollar corporations. They are energetic entrepreneurs. Museums have become businesses that must watch the bottom line.” While acknowledging the old-fashioned rationale for museums and museum-going, Pillsbury also allows that teaching and pleasing are now handled in ways appropriate to Disneyland. “Museums can no longer be places of refuge.”

But why not? Is there no place left for solitude, contemplation, and solitary wandering, away from noise and crowds? The role of the curator has been diminished. The DMA, after Jack Lane’s departure, made the interesting (or audacious) decision to promote to the directorship Bonnie Pitman, who has a background in education, not art history. How different from the recent decision at the Metropolitan to replace Montebello with the quiet, understated Thomas P. Campbell, whose expertise in baroque art led him to curate two totally surprising blockbusters at the Met on Renaissance tapestries. Across town at MoMA, Glenn Lowry had made his own mark as a distinguished Islamicist before being tapped to hobnob with the Rockefellers and other donors. In Texas, it looks as though such scholarship is valued less than other directorial assets.

Rick Brettell, former DMA head, says that a director has to have a good knowledge of the local scene, business models, “branding, and marketing.” “Branding”: now there’s something for a Texas director to sink his metaphorical teeth into. The old ability to charm donors, and the public, by saying that a picture, or an exhibit, is worthwhile, now takes a back seat to handling resources. Always optimistic, Brettell says that if a severe recession reduces museum staffs by 50 percent but keeps the essential functionaries in place—guards, cleaning staff, docents, and curators—perhaps the museum could return to its original educational functions, albeit with an updated look. Brettell envisions a time when “virtual” exhibitions replace blockbusters, because the costs of moving art will become prohibitive. At the very least, we may have fewer blockbusters, like the King Tut extravaganza, and move closer to the kind of smaller, didactic specialty shows, in which the Kimbell has always excelled.

What Brettell doesn’t say, of course, is that nothing can ever substitute for the actual experience, one on one, of looking closely and long at a work of art. Spending money on websites is a sorry substitute for engaging people’s eyes and minds. But it may be all that a museum will be able to do. On the other hand, according to Bonnie Pitman, the DMA is in better shape than many other museums. The Tut exhibit, which closes on May 17, has sold about 400,000 tickets so far, but experience has taught her that most people in Dallas wait until the end of a run and then rush in. So perhaps Tut will triumph at the box office. So far, she says, “we have been able to manage with the resources we have.” That is, no layoffs or cutbacks have yet been made. The DMA has had a balanced budget for 12 years. Good for them.

Dallas and Fort Worth are awaiting both Lee and Strick. They have their work cut out for them. Their two museums are apparently in good financial shape, better certainly than the financially mismanaged Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, which Strick has just left. Lee, especially, is relatively young and untried. But, we must remember, so was Pillsbury when he left Yale for the Kimbell. So were, going way back, Alfred Barr at MoMA, James Wood at the Art Institute of Chicago, and Philippe de Montebello himself. Strick says he wants to focus on education and exhibitions. But sculpture outweighs painting, and moving it, especially big pieces, is not easy. Strick wants more contemporary coverage, more traveling exhibitions, colloquia, and publications. He has big ambitions. Will he have the financial resources to realize them?

What will happen if the bottom just falls out of the economy? In the case of a museum, would it be a bad thing if all it had to offer was the riches inside? Maybe not. Maybe we’ll have to readjust our eyes and, instead of going for the next best thing, be satisfied with, and grateful for, what we already have. Maybe we might look at the Old Masters, the tried and true, and the familiar pictures and sculptures again. And again. Familiarity need not breed contempt, or even boredom. It might encourage depth of looking, and the slow accumulation of wisdom.

Welcome, Messrs. Lee and Strick, to North Texas. And good luck. You’re going to need it.

Write to [email protected].