But she also thinks she would refuse any man who loved her, because she couldn’t stand the failure. Pinkie says she is wrong.

“But it wouldn’t be fair to him,” Pinkie says, “if he’s willing for happiness, even if only for a week or a month.”

Judith develops an ironic stance to the possibility of her death. In the Civil War cemetery, she clowns behind an old tombstone.

Judith cuts her off. She is hard to talk to, hard to comfort, and deeply suspicious. Pinkie knows how to talk to her. Judith has to be the leader. If she wants to talk, Pinkie lets her.

One day Sandy is sweeping the floor, and Judith tells her to stop.

“I never sweep. The dust rolls up against the baseboard, and I smooth it out of the room with my feet.”

Thanksgiving is bad. Too many people are gone out of town, and Judith feels miserable and disappointed.

She has thought about suicide for months and has even saved up a stash of Seconal, but by December, it becomes obvious that she has waited too long. She’s having trouble swallowing now and she would need alcohol — and help. When someone asks her if she doesn’t yearn for peace, she says, “I can’t believe you asked that question.”

She declares to Pinkie that she will die between Christmas and New Year’s. Her breathing is heavy and gasping, in part from the morphine, which depresses the central nervous system.

She has forbidden the holding of a funeral service, but Barbara asks if they can have a memorial reading. She agrees and starts picking poems and songs.

Dec. 17 is the beginning of Hanukkah. Barbara brings her children, and they light the candles. Judith directs the making of potato pancakes and shortbread cookies. She comes out in the wheelchair in a white nightgown trimmed with blue lace to watch Barbara’s children light the candles. She learns a song from Barbara and her children and sings it for Frances on the telephone.

I had a cow down on the farm.

Golly ain’t that queer.

She gave us milk without alarm.

Golly ain’t that queer.

One day she stood in an icy stream.

Golly ain’t that queer.

Froze her tail clear up the seam.

And now she gives us all ice cream.

Golly ain’t that queer.

All this time Judith keeps her parents away, but her friends tell her they will summon them when the time comes. One eye is swollen and blurred. Her face is yellowish and dark with pain. She says there is nothing of her left, but her friends insist she is there and she must not doubt herself. When Barbara reads her some Psalms, Judith punctuates them with “B.S.” and “Not True,” but has her keep on reading.

Although she attacks Christmas as a hypocritical time of gift giving, Judith strings colored macaroni and popcorn and decorates a small tree set on the wheelchair and pushed close to her bed. She sends out for a bag full of spices and makes potpourri. She fills every available chatchka in the house, including a Moosehead beer bottle and Chinese slippers, and invites her friends to choose. She delights in watching them choose.

She becomes more and more conscious of everything she eats and excretes. She doesn’t want anything disturbed. She puts a note on the clear plastic catheter bag:

“Please keep this bag where it is. We understand some important things are not attractive. In this case, gravity greatly enhances the eliminatory function. So let me repeat, do not move the bag to the other side of the bed.”

Toward Christmas she grows worse. She is retching. Her eyes are purple and defiant and angry.

“I love you very much Judith,” says Barbara.

“Shut up.”

“I want to say something. I must be very careful. I don’t want to be corny.”

“Don’t be corny.”

“By being so much yourself you’re giving us a lot.”

“I’ve never felt less like myself. I want you to know I am shitting all over the place.”

Two days before Christmas it doesn’t seem she will last much longer. Frances calls Judith’s parents, David and Ruth Steinberg, who rush to the airport. Nina, who grew up knowing the Steinbergs, meets them at the airport. When she phones Judith’s house from the airport, there is no answer, and she fears she is taking the Steinbergs to a dead child. When they get there they discover someone has kicked the phone cord loose from the wall. Judith stirs.

“Hi Dad, Mother. What’s the bad news?” she says.

“We’re here with you, Judy,” they say.

Judith picks up a little. Her parents insist that everything will be the way Judith wants it. Her dad fixes the car; they both run errands. To give them a shopping list is to make them happy.

Two days before the new year, Judith insists on being taken to the porch in the wheelchair. She is gaunt, her belly bloated; the tumors pebbling her skin are frightening. She is wrapped in a bright patchwork quilt and wears a straw hat, blinking in the wind and sun. She is happy to have friends there, all women.

“I can’t think of one man I want here,” she says.

“Not even your grandfather Steinberg?” her mother asks. “He was a nice man. During the war he took me out to dinner every night.”

“And tried to put his hand up your dress.”

“He never put his hand up my dress.”

“Oh come on, Ma, tell the truth.”

“He wanted to stay alive to play pinochle with you.”

“I would have beaten him.”

What about X? someone asks.

“A shit. He came to visit every two years.”

How about Wade?

“He had to be nice, he’s June’s son.”

Kirby?

“He’s nice.”

Dr. Z?

“Ah. There’s a man. But he’s not too bright. He’s nice though. But not too bright.”

What about A?

“You want to know what I liked about A?”

His intelligence? someone guesses. Gentleness? His cleanliness? His tennis?

“Yes, I’d rather watch him play tennis than almost anything. He gave it everything he had. He didn’t hold anything back. But there was nothing you could do to get him to put his hand up your dress.”

A week later she is depressed. She longs to go to the garden but is too weak.

She cries because she is so young and hasn’t had a baby.

“I would really like to be a mother,” she says.

“I’ll let you adopt my grandbaby,” Pinkie says.

“Are you kidding?”

Pinkie takes a photograph from her purse and shows Judith the baby.

“I don’t mean you have to sign papers, but from my heart to your heart, this could be your baby.”

Judith cries.

Judith’s constipation is bad. Her belly swells. She is in danger of dying of her own waste. She is in and out of sleep by the third week in January.

When she is about to be moved and appears to be sleeping, Sandy proposes they wait until she has swallowed a bit of bread she asked for.

“That’s right,” says Judith, with her eyes still closed. “She may appear to be asleep, but she’s no dummy.”

Sometimes she thinks she’s not in her house and has to be reassured.

“Why do you think you’re in Australia, Judith?”

“Beats my ass.”

She decides that the cat is not her cat but another one that came in the mail, and looks like Sadie and wears Sadie’s tags. She demands the cat be kept away for a couple of days, and then, as abruptly, welcomes her back.

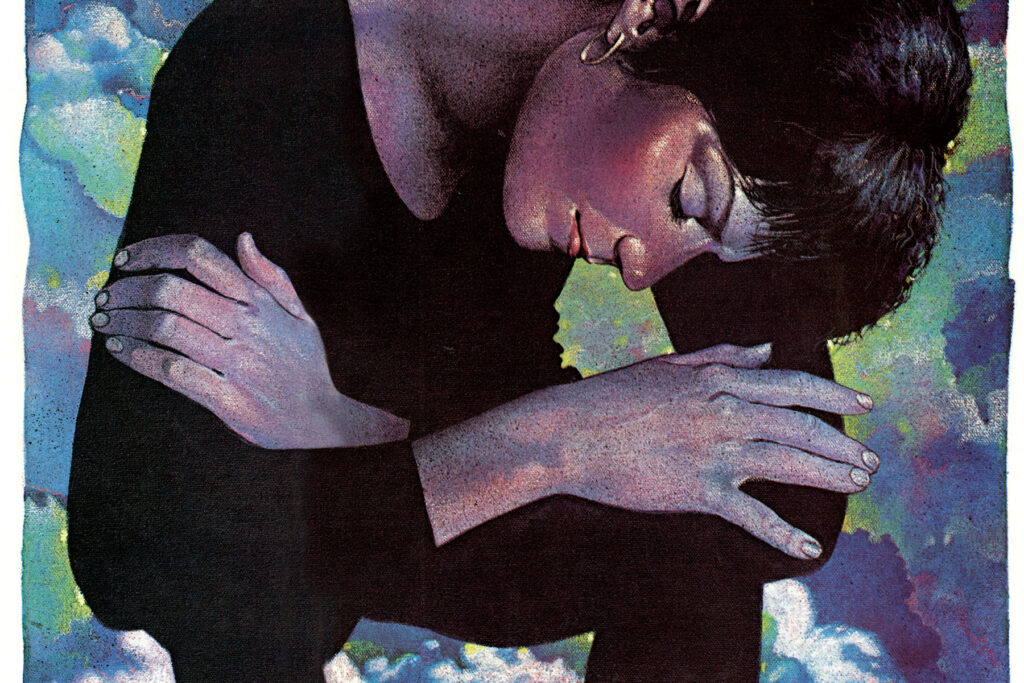

For three days she drifts between living and dying. Kirby comes in and holds her hand and feels enough pressure back that he believes she knows him from his thick, short fingers. Barbara brings in two yellow blooming branches of forsythia. A single tear comes from Judith’s eye. The other has grown swollen and red and tearless from the pressure of a tumor.

By the third week in January, Judith is in a coma. Thursday, Jan. 22, June and Frances rub her with lotions and leave for the night. Sandy is sleeping in the other bedroom. Florence is working the late-night shift. Everyone is exhausted.

Sadie is nervous. She paces around the room and jumps into Florence’s lap, which she has never done before. When Judith sleeps, her eyes are half open, the irises showing. At 2:30 in the morning, in a house blocks away, Barbara’s baby falls out of his crib with a crash and starts crying.

Florence goes to the other bedroom and awakens Sandy.

Judith is dead.

They call Frances and June. June gets there first and finds her as Florence found her. June closes her eyes and covers her with the blanket. Her parents come from the apartment they have shared with Judith’s friends the last five weeks. When the mortuary driver comes, they stand in the backyard until Judith is carried from the house.

Judith is cremated wearing her silver, hooped earrings.

At a simple service a few days later, the poems Judith selected are read.

Frances sings a traditional “holler” that Judith loved:

Pay day, pay day.

pay day at Coal Creek this morning.

The last thing they read is a poem of Judith’s, “Spirit Song”:

This flute I’m playing

wakes the insects,

who are sleeping at my feet.

The plants in the fields

cry all night long

for their cousins.

Even the dew is anxious.

What sounds in the dark

is not some gentle mewing.

It settles, small and wet, in the folds of our clothes.

There are ladders

in the air, and circles.

What creature isn’t

listening, moving?

I tell you, I will not

leave you, though I sing

as you die. I heard this

in a song: pass it on.

Her ashes are sent west, and scattered in the mountains.

Author