When the ice storm of 1979 hits and Judith loses all the power in her little duplex on Palo Pinto, Kirby arrives with hurricane lamps and a Coleman stove. A tree on her street cracks and splits, and she writes a poem about it, thinking of her own possible death. Kirby digs a garden for her. She plants tomatoes, lettuce, onions, beans, and her poems acquire vegetables.

Kirby and Judith develop an ironic stance to the possibility of her death. She clowns in the Civil War cemetery near the convention center. Behind an old tombstone she stands in jeans and red sweater, as though to say she is not frightened. She has a little triptych of the photographs made there and sets it in her living room.

She writes Frances a birthday letter in the fall, four typewritten densely worded pages about love and work. Judith believes it is possible to have both, will not give up on either one. She sees her life as a poem she is writing, and though the poem won’t be perfect, it is the living of the poem, the loving and the working that make it possible to continue. “Only the work counts, the conversation between you and yourself.”

The circle of friends sustains her. She finds a poem by Charles Wright that she likes well enough to copy and keep around. The last stanza could be about her friends:

This world is a little place,

Just red in the sky

before the sun rises.

Hold hands, hold hands

That when the birds start, none

of us is missing.

Hold hands, hold hands.

• • •

Contingency: Dallas, Spring 1980-Jan. 1981

Listen to this, Miss Bell: Contingency (fourth definition, Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary.) “The fact of existing as an individual human being in time, dependent on others for existence, menaced by death, dependent on oneself for the course and quality of existence.”

By New Year’s 1980, Judith has spent 18 months in full remission. She has to stop taking adriamycin but continues to take other drugs. Her hair begins to grow back, at first, a fine, sparse baby’s hair. Judith is pleased.

Within three months, she finds a lump in her leg. It’s removed and found benign. Then another appears. She shows it to June in the restroom.

Frances is on the phone at the reference desk when she sees Judith walk off the elevator. She has returned from the pathologist and gives her a look of despair.

Weisberg has nothing left to treat her with. He suggests she go to Houston’s M.D. Anderson Cancer Clinic for tests and recommendations. She does, but they have nothing to offer, not even an experimental therapy. The only thing she can do is begin another course of adriamycin and have her heart monitored electronically.

“I’m really scared,” she tells June. What should she do about taking the adriamycin, she asks.

“I would like to see you here as long as I can,” June says.

“That’s what I want to hear.”

She dreams she is in an upstairs bedroom like that in which she grew up. She tries to turn on the light, but it won’t work. She tries lamps, one with a three-way switch, and flashlights. The bulbs are there, the switches sound right, but nothing will light up. She wants the light on because she can’t sleep.

It is being in the dark and unable to do anything that bothers her. She wants to be able to at least define the darkness, give it boundaries. Cancer is an experience of being out of control, with no explanations, no understanding. She writes the dream down in an attempt to understand, knowing already the limits of understanding she can get from writing.

She decides she needs to learn to float, to accept the unavailability of explanations and to trust her past experience of the limited nature of all things.

She sends Frances a note with some lines by Adrienne Rich that expresses her gratitude for her loyalty:

But gentleness is active

gentleness swabs the crusted stump

invents more merciful instruments

to touch the wound beyond

the wound

does not faint with disgust

will not be driven off

Judith begins preparing for her death. She has a list with 20 names titled, “People willing to spend nights.” She convenes a meeting with a hospice worker and several friends. She fears most that her death will be taken out of her hands. She wants to die at home in Dallas, and not be sent to New York, where, she fears, her parents would take over.

“Who thinks it would be a good idea for me to go home to my parents?” she asks the meeting.

Frances says maybe it would be a good idea not to close that door. Judith is furious. Frances is so upset that she has to leave the room.

No one wants Judith to leave.

Caring for Judith during her chemotherapy has already been exhausting. Frances is not sure they will be up to handling her death. Making promises is fine when Judith is still in relatively good health; she wonders whether they can handle a prolonged, serious illness.

It takes days for the breach to heal.

Judith makes Sandy a signatory for her bank account. She draws up a will and names Frances executrix. The will includes not only her savings and automobile, but also her baskets, jewelry, post card collection, Navajo blankets, books, even a rosary the unbelieving poet wants to send to a friend in Florida. She secretly writes the names of friends on slips of paper and places them in her Indian vases.

A tumor difficult to detect presses on her sciatic nerve, giving her severe pain in the hip and leg. Nina and Judith dub it the “tushy monster.” That summer she begins taking dilaudid, and when the pain intensifies she takes liquid morphine, a grape-flavored, purple elixir she dispenses from a plastic squeeze bottle into a measuring spoon.

In the midst of her despair she has good news. She phones up Jack, saying she has had a poem accepted by Harper’s.

“What d’ya think of that, Myers?”

Harper’s takes “Water,” part of a six-poem sequence called “Mending the Circle”:

There is always a journey

to the sea, friend.

Put my bones in a good jar

for the salt is very hungry

and I want to rest

a while on the water.

Waves, like the cool white hands

of my dreams, lift me, carry me

home.

One night she dreams that she is with all her women friends and some little girls on a grassy hill. They wrap themselves up in quilts and roll, laughing, down the hill.

Judith takes Nina shopping for a birthday present. She insists she pick her own Guatemalan huipil.

Nina is overwhelmed, doesn’t feel deserving, and can’t choose.

“Make up your mind,” says Judith. “I won’t be able to do this much more.”

“It’s too nice,” says Nina. “I feel funny.”

“That’s your problem,” says Judith.

Judith continues to work at the library, but sometimes she needs to rest while she reads. A cot is set up in a back office for her. Her colleagues do part of her work for her.

She walks with a limp from the tumor in her leg. After four more months of chemotherapy, the tumors show no signs of disappearing. Some are removed surgically, to relieve the “tumor load” from the chemotherapy, but the others persist. They show up in her lungs in the X-rays.

The doctors and she decide to stop the chemotherapy. She has some signs of heart damage. Nothing can be done except take medication for pain, and wait. She insists on working as long as she can. She organizes her poems into a manuscript and binds 30 copies into folders for her friends. The title is This Leaving We Cannot Live Without. She plans to enter it in a poetry contest. She is disappointed she can’t attend Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in Vermont that summer.

June and Frances organize a new schedule so that someone is with her constantly. They figure that two of them will need to be with her every night. They begin to wonder if they can do it. They are already exhausted from the long months of chemotherapy.

Judith stops going to work Nov. 11. Within three days she has to be catheter-ized. Her world becomes her bedroom with its ugly blue-green paint and dirty ceiling tiles. Her friends want to paint it, but Judith refuses. She insists that absolutely nothing in her house be changed. She will command from her sickbed.

One of her best poems, “In the Swaying Field,” is a metaphor for what she does. It’s based on a story Kirby has told her about a man who commanded two dogs in a field by hand gestures alone. Like a conductor leading an orchestra, he directs them across the field, circling, dancing.

The pain becomes worse, and Judith wants more morphine. Helpless to cook for herself, clean herself or care for herself, she at least has command of that. Her friends are troubled that she is taking so much she is nearly incoherent. June and Frances are exhausted and worried.

Judith wakes up from dreaming and June’s there.

“Was it real that I had the baby?” she asks. “Or is dying from cancer real?”

June hesitates for a terrible moment.

“The dying from cancer is real,” says June. “Come on, I’m going to give you a bath and then breakfast.”

Frances thumbs through the insurance booklet and discovers rescue. The library’s medical insurance provides for around-the-clock nursing. Within hours, Pinkie Cotton, L.V.N., is at the duplex on Palo Pinto.

She is a large, calm, competent woman. She surveys the situation and goes into action. The friends are loving but hopeless amateurs compared to Pinkie.

Her first words to Judith are, “You’ve got to wake up and look around.”

In Pinkie’s mind, Judith is wiping herself out with drugs. She wants her alert, at least part of the day. Pinkie shares the duty with Florence Bates, who takes a similar, loving, hard-headed approach. Neither of them can be manipulated, especially by Judith.

The house is a constant scene of friends visiting. Someone usually spends the night on the “marshmallow,” a long, white Naugahyde sofa Judith found at a garage sale.

Florence looks at the spare furnishings and improvised bookshelves and tells Pinkie that Judith must be poor.

“See these crates around here?” says Pinkie, pointing to the bookshelves. “That’s not poverty, honey, that’s art.”

When Judith cuts back on her morphine, she starts living a little more, hurting a little more. She commands the cooking, orders up the ingredients for tuna salad, and mixes and stirs the bowl while in bed.

Although her friends fill the house with food, Judith plans menus and insists on eating her food when she is hungry.

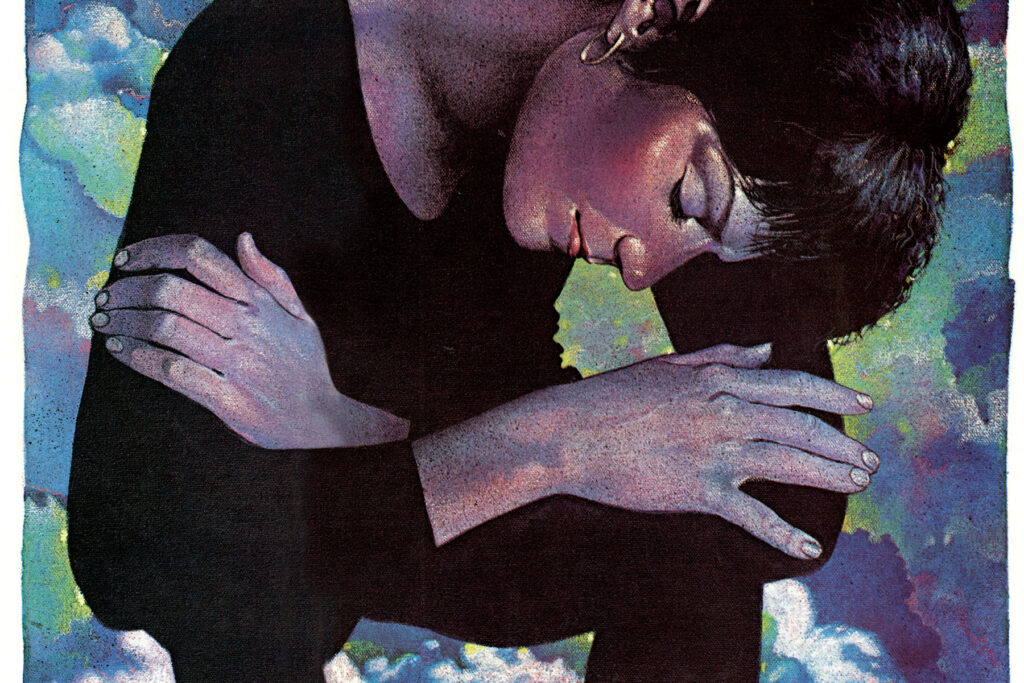

She puts on her makeup, carefully, professionally. She gropes for cosmetics in a shoebox and makes herself up lying flat on her back. It takes as long as an hour and a half.

The tumors spread onto the surface of her abdomen. Another swells behind her liver.

Shortly after the nurses come, Judith stays up one night, chanting like an American Indian.

She takes amphetamines to counteract the drowsiness produced by the morphine, but this appears to sometimes make her delirious. But she doesn’t stop being herself.

Once she hurts Frances’s feelings and Frances turns red.

“When you get mad you smell like an apple,” says Judith. “Don’t you want to hit me? Don’t you want to punch me?”

“I don’t express my anger that way,” says Frances.

“I don’t know why you put up with this.”

“Because you know she’ll take it,” says Pinkie.

Barbara Orlovsky, a poet and mother of three children, comes frequently and reads to Judith. At first Judith believes books are the answer. She sends a note to the library asking for fiction titles:

“This is HIGH PRIORITY — over food, laundry, back-scratching, feet-rubbing, etc., and just under morphine in importance.”

To her distress, she can’t read them, though the librarians pile in nearly 200 books. She thinks if only she can find the right book, her confusion will end. Being read to and talked to works better.

Author