Change: Dallas, Summer 1977

Judith flies to Dallas to interview for a librarian’s job in the humanities division of the public library. She has borrowed a conventional dress for the interview. Her experience in public libraries and her credentials — BA and MA in English, MA in library science — make her a likely choice for the job.

She is determined to get it. She has a clean bill of health from a doctor, a strong love of books (especially contemporary poetry) and wants to change her life.

She is leaving her husband.

They have moved to Cincinnati, where he has a library job. Judith has none. She has tried to manufacture greeting-card verses, but sells only a few. Her mind isn’t formulaic enough. Then she finds a lump in the fatty part of her chin. A surgeon removes it, and pathologists say it is malignant. The doctors are pessimistic. Her husband begins giving her up in his mind. A poem, “Husband,” grows out of this:

Each morning, outside the east

windows, the birds squawk furiously,

recalling me to my life, willing

to sell my secrets for a nickel

to the first person who asks.

Is that what you call the abstract

prerogative? I have

a small lump in my throat

right now.

You think it’s another story,

but I know better.

Our telephone lines connect

in black and buzz

all along my lit-up veins.

I whisper tender things

at the mouthpiece, and

fish swim out your end,

glittering their fins

for all they’re worth.

Boundaries, ah, if only

you’d asked, were never

my intention.

The boundary he cannot deal with, Judith thinks, is that she is going to die and he must live.

He is faithful, he is devoted, he is considerate, but that is not enough for Judith.

One day he comes home and finds her sitting on the couch, crying. He puts his hands over his ears and walks out of the room. She cannot see his pain, for what is his pain compared to her terror?

Then the pathologist changes his mind. The tumor is not a liposarcoma but a lipoma. The two are easily confused. The lump was benign. The doctor expects Judith to be delighted, but she is furious. He can’t understand why. Her husband has yet another adjustment to make.

Suddenly she has been given back to him after he has given her up for dead.

The tension is too much for Judith. She finds an ad in a library publication and applies for the job in Dallas. The doctors send a letter to the library about Judith’s cancer surgery and the benign growth removed from her chin. Her health is good. She joins the downtown staff of the Dallas Public Library and is immediately assigned to selecting poetry and literary criticism. She sets about building the library’s collection of contemporary poetry into one of the best in the Southwest, better than that of many college libraries.

Within months after leaving her husband, Judith is divorced, and her husband remarries.

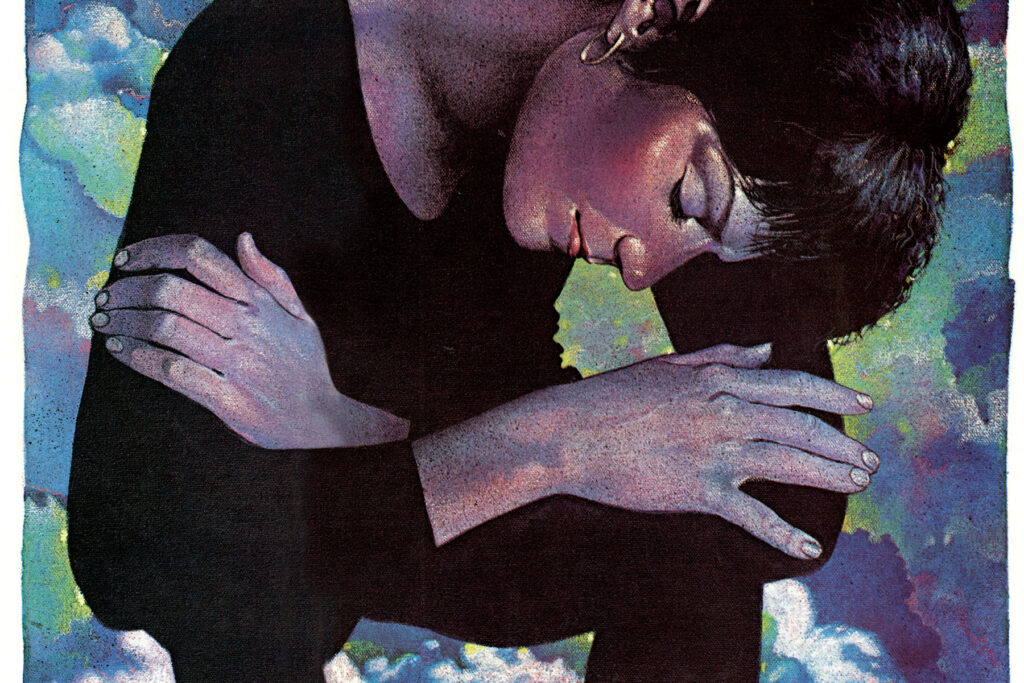

As soon as she starts work, she shows up in trousers and bright sport shirts, gypsy skirts and hoop earrings, Indian jewelry from her student days in New Mexico, striped knee socks. She stays with another librarian for a week while she looks for an apartment and finally finds one in East Dallas. She is almost ghost-like when she stays with the other woman, so careful is she to avoid disturbing her household.

She begins to make friends. The first she finds is her boss, Frances Bell, the head of the humanities division of the library. She is older than Judith, shyer, sweet-faced, deeply intelligent. Judith decides Frances is a frustrated artist, and plunges her into frank and strong friendship.

She finds Kirby Metcalfe, the library’s artist and exhibit designer, also poet, ceramist, modeler, and self-confessed self-promoter. Kirby is short, rotund, with a carefully trimmed gray beard and a round, jolly face. Sometimes he wears wide red suspenders. Judith knows a fellow spirit. One day she comes up to him and says: “I’d like to be your friend. My name is Judith. What’s yours?”

And there is June, the organizer. She’s the mother of three grown children and a teenager. After her full-time job at the library, she reads proof for local editors, who call her “Mom” Leftwich. Once June makes a decision, she acts.

Nina Israel, eight years younger than Judith, grew up in the same middle-class neighborhood on Long Island as Judith. She is girlish, sisterly, a little insecure. She is someone to giggle with. Judith gives her confidence in herself, because Judith expects it.

Sandra Halliday, of the fine-arts division, is methodical, quiet. Judith picks her out, too. Months after they have known each other, Judith and Sandy are looking at photographs of friends from the library when she comes to one of Sandy, and says to her:

“You know, I tried to get to know her, but it wasn’t easy.”

Judith doesn’t seem simply to make friends, but has a policy of making them. She singles them out, focuses her attention on them, finds out about them, and insists they respond. For some, she is too intense. They back away.

Judith, bright and cheerful, slim and young and beautiful with her large hazel eyes, strong cheekbones, wide laughing mouth and her confident way brings a spirit of levity to the humanities division. She masterminds parties. The humanities division becomes a livelier, more cohesive place.

She writes a note to a friend of Frances’ who refuses to get medical treatment for an injured foot:

Dear Drew,

The subject is hurt feet. If I were a hurt foot and my employer refused to recognize my pain, I would go on strike. I would organize the other feet, hurt or not, and shout, “Walkers of the world, unite.” I might even incite a riot or stampede. And I certainly would get someone to look at me, and find someone to tell about the cruel and unusual punishment I was receiving at the hands of my boss. I would not like very much being twice my usual size; nor would I want the rainbow hues anywhere but in the sky. What I would want is a gentle bath, some foot-wise attention, and a bit of good advice. About how to get myself back on the ground, etc. In good faith, I must warn you that as a potential employer, you may have your walkers organized out from under you, so take care.

Judith

Judith is a socialist in sentiment, if not in practice, and the following spring, she asks the librarians to think about having a May Day party. The party is never held, for Judith is gone from work that day. She is in the hospital having lumps removed from her abdomen and leg. Two others have turned up in her lungs. They are liposarcomas.

Judith distrusts doctors and hospitals by this time, hates their coldness, hates their lack of humor, hates their lack of compassion. But she finds a cancer specialist she likes, Robert Weisberg, a New York Jew, a guy who can take her needles and wisecracks and give them back. Weisberg usually wears jeans, a silver bracelet. He’s bearded, dark and nearly Judith’s age. He’s also tough and thorough. He believes in a thorough treatment of cancer with no letup just because the patient might feel a little better. He doesn’t like postponements; he doesn’t like skipped treatments.

He can’t offer Judith much. Radiation doesn’t seem to affect liposarcomas. Chemotherapy succeeds in less than a quarter of the cases, but the effects of chemotherapy on the tumors can be detected within two months after beginning treatment.

They begin immediately with chemotherapy, five afternoons a week every fourth week. The drugs are adriamycin, cytoxan, vincristine and DTIC. The adriamycin can damage the heart if taken too long. The other drugs can affect the blood. Part of the procedure of chemotherapy is to monitor the heart carefully and take monthly blood tests.

Part of the procedure for Judith is to mobilize her friends to help her through the chemotherapy. They are frightened, but they plunge ahead. June organizes a schedule and sticks it to her refrigerator door. The first day of the five days is the roughest. Someone takes her to the doctor’s office on Harry Hines Boulevard where Judith reclines on a high table covered with leatherette. The nurse tanks two bottles, a red one with the adriamycin and a clear one, connected to a y-tube, and sticks the needle in Judith’s arm. She must wait for an hour and a half or two hours while the chemicals drip into her vein.

Forewarned of the nausea of chemotherapy, Judith brings her own plastic bait bucket and plops it on a nurse’s desk. She has a favorite treatment room of the four in Weisberg’s office. From there she can see the nurses’ telephone and she can give a cute doctor there the eye. The nurses laugh and watch him come by to make a phone call from their phone just so Judith can get a look at him.

Going home is not so good. Mondays she throws up in the bait bucket while Frances drives. Unable to eat, Judith lies down and heaves. When the worst is over, Frances cooks something frozen for herself and spends the night with her. Whoever is assigned to drive her talks to her, to keep her mind off the nausea. Once in a while she tries smoking a joint, but it doesn’t seem to help. By Wednesday, it is a little easier. Wednesday she goes to June’s house. She gets into her nightgown and lies down at one end of a long couch, with June’s black Labrador retriever, Othello, at the other end. Judith refuses to own a television herself, but on Wednesday nights, she watches television with Robbie and Genie, June’s daughters.

“I love this guy Starsky,” she says.

She can eat a little fruit or cheese.

There is a lot of passing around of food. Judith will take a spoonful and pass it to the others, saying “Here, taste this,” challenging them with her eyes to be afraid.

One afternoon, three weeks after her first chemotherapy, Judith is sitting at her desk in the library. She passes her hand through her thick, curly brown hair, hair so curly a woman asked her at the movies where she had gotten such a wonderful permanent. She is prepared for this. She passes her hand through her hair and thick clumps of it come out in her hand. A librarian drives her home where she brushes the rest of it out with a brush, and ties a scarf around her head. With Kirby and Frances, she decides she will not wear a wig. She wears scarves for the rest of her treatment, and is as striking as a fashion model, Kirby thinks. As for the nausea, she says, “So I throw up for two or three hours, what’s so bad about that?”

Within three months the lung tumors have disappeared. She continues the chemotherapy, five days of every month. She doesn’t miss. She continues ordering books and writing poems. One day Jack Myers, a poet at Southern Methodist University, gets a note from her about library business. She writes a small poem at the end. Myers calls her up. Poets have got to stick together, he says.

“Before you meet me, there’s something you have to know,” she says.

“You’re sick,” says Jack. “You have cancer. That doesn’t matter.”

“I’m dying. I have maybe a year to live.”

They meet on a kind of blind date. She wears a red scarf.

“Want to see what I look like?” she asks in the car.

She takes off the scarf.

“You look great. Okay.”

They go to a bar and talk poetry.

Judith has a crush on Jack, but nothing comes of it. They settle in as poetry pals. She takes his poetry workshop in the spring, sitting in when she is up to it.

“I’m very smart,” she tells him. “I’m very bright, and I’ve read a lot of poetry, but I need help technically.”

It’s a deal. Jack promises her that he will be mercilessly critical, demand the utmost. She responds by working hard. When the new poetry books come in to the library, Judith reads them hungrily, phones Jack up and gives him a critique, a kind of poetry hot line.

She’s also hard on Jack’s poems.

“This line stinks, Myers,” she says. “Sometimes you write brilliantly; some-times I don’t know.”

Talking to Judith is like sticking your finger in a light socket, Jack thinks. She elevates the poetry class. And she keeps zinging him.

“Myers, you don’t know how good you are. If you did, you wouldn’t write like this.”

She zings him and leans back and says, “What do you think of that?” and challenges him with her hazel eyes.

She is writing out of rock-hard despair, Jack knows, because she believes she hasn’t much time, and she has a lot to learn about making her poetry sound and sing. At this rate, in five years she could win a national reputation, he thinks.

Poetry is not decorative, she writes in her notebook, but is chaste and desperate. It is an attempt to pare away lies, then find a core of lies that can’t be touched and are acknowledged as necessary. By turning toward the process, the poet tries not to get an ultimate, definable truth, but a sentence, a phrase, a picture, that is perhaps a little truer. Humility is necessary, and she underlines the resemblance of the words, humility and human.

“AND A SENSE OF THE SMALL-NESS EVEN FUTILITY OF THE JOB,” she writes in block letters in a notebook. “AFTER ALL, A JOB, SMALL INTENSE TOUGH JOBS, ARE (MAYBE) THE PROPER HUMAN ACTIVITY.”

Jack compares the writing of a poem to the challenging of an obstacle, a wall. Tunnel under it, punch through it, leap over it, dissolve and pass through it. Judith writes a poem about this that ends:

Over, under, or through,

it matters only

like the tombstone says this

person was and isn’t it matters

because we want to get it

get it right it matters just

a little to the wall.

She writes him a note that ends: “Your class is lovely, makes me happier than ever to be still whinnying.”

She writes in a notebook: “I could write a list of hates to fill this page: all people. I leave it blank and try instead to allow blankness to seep into me: to have a good heart.” She draws a heart on the page with an arrow through it.

Get the FrontRow Newsletter

Author