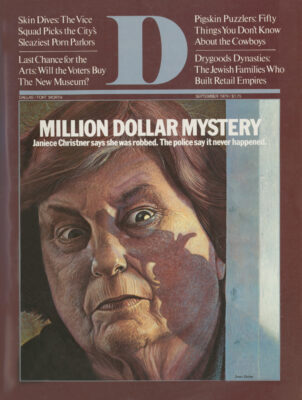

O

n a hot afternoon in late August 1978, Evelyn Harris was polishing silver in the kitchen of the spacious Highland Park mansion where she lived and worked as a housekeeper. It was quiet in the house; Evelyn was alone. Her employer, the owner of the house, a wealthy 61-year-old widow named Janiece Christner, was on an errand; she’d gone to look at an antique rocking chair. Evelyn, a big black woman, had worked here at the Lakeside Drive mansion on the shaded banks of Turtle Creek for over five years. She was comfortable here, a part of the family. She went about her work quietly and contentedly.

Polishing silver was no ordinary chore in this household – it was an ongoing artistic endeavor. Mrs. Christner was a collector of fine silver, and the house glittered with the craftsmanship of such renowned silversmiths as Paul Storr and Paul DeLamerie. Mrs. Christner had also assembled a fine collection of the stunning jeweled and enameled creations of Carl Fabergé. Her real passion, though, was Continental porcelain – vases and bowls and plates and figurines of Sevres and Meissen; Mrs. Christner’s collection of European porcelain was considered one of the finest in the world.

It was, for Evelyn, an intriguing household in which to work. Dusting was more than just a menial task when the object at hand was a pair of Meissen bitterns worth $70,000. The job of polishing silver took on added luster when the cloth was put to a pair of DeLamene George II sauce boats worth $25,000. It was more like being a caretaker in a museum.

The eccentricities of the house went beyond the collections. The collector herself was an unusual woman. Often she would stay up late into the night, poring over her art books and auction catalogues, tracing the history of this figurine or that vase. She would sleep late, forego breakfast and lunch, and pass the day with a steady diet of coffee and Camels, wearing bedroom slippers and robe. As ever-present as her cigarettes were her dogs, three tiny Yorkshire terriers – Buttons, Wee Bit, and Puddin.

Today, as Evelyn polished silver in the kitchen, her only company was the pet myna bird, Fish, whose chatter always filled the house. Whether cackling nonsense (“I’m a fish. Swim.”) or screeching blasphemies (“Well I’ll be goddamned”) or doing abstract impressions (an extraordinary rendition of the opening and closing of the squeaky oven door), Fish was the emblematic centerpiece of the Christner household museum. Evelyn liked Fish, she liked Mrs. Christner, she liked working here.

The doorbell rang. Evelyn put down the silver and walked through the dining room towards the foyer. The wide front door of the Christner home is partly of paned glass; the door looks out to the east over the terraced front lawn and down to Turtle Creek. A thin white curtain covered the glass, but anyone on the porch could be seen hazily through the curtain. As Evelyn approached the door, she saw a tall, pretty young woman with long blonde hair standing on the front porch. At first Evelyn thought it was Mary Ellen, a former girlfriend of Russ, Mrs. Christner’s 20-year-old grandson, who had been living in the house all summer but had just returned to college in Alabama. But as she got closer to the door, she saw that it wasn’t Mary Ellen; it was someone she didn’t recognize. Evelyn never opened the door to strangers. She returned to the kitchen and punched the intercom.

“Can 1 help you?” Evelyn asked the girl.

“Is Russ here?” the girl replied.

“No, he’s gone back to school.”

“Do you know his address at school?” the girl asked.

“No,” said Evelyn, “and Mrs. Christner isn’t here right now.”

“May I leave my address for him?”

“Sure,” said Evelyn. “Just leave it in the mailbox.”

“I don’t have a pencil. Can I borrow one from you?”

“Well,” said Evelyn, unwilling to open the door, “I can’t. I’m busy right now.”

The girl said nothing more. Evelyn went back to polishing silver. Later she went out on the front porch to check the mailbox. The girl had left no address. Evelyn didn’t think any more about it.

On a Sunday morning, September 24, about a month after the visit of the unknown girl, Evelyn Harris dressed and left the Lakeside mansion to go to church. As was her habit, she would take the afternoon off and return to the house about five o’clock. Around noon, Mrs. Christner’s physician, Dr. J.C. McNamara, stopped by the house to give her a diet pill. Shortly after the doctor left, some time around one o’clock, Laurie Ann Christner, Mrs. Christner’s 19-year-old granddaughter, a sophomore at TCU who was staying at the house, told her grandmother she was going to play tennis and left the house. Mrs. Christner was alone.

Some minutes later, Janiece Christner got up from her chair where she had been reading in the study at the south end of the house and went into the downstairs bathroom. She heard the phone ring, but didn’t answer it. Then, as she returned to her study, the doorbell rang. As was often the case on pleasant days, the front door was open but the screen door was closed and locked. As they always did when the doorbell rang, the dogs scampered to the front door, yelping.

Mrs. Christner, still in her morning dress, walked through the living room and into the foyer. Through the screen door she could see a tall, pretty girl with long blonde hair, wearing light-colored slacks, a light jacket, and large sunglasses. Over one arm, she carried a man’s blue velveteen sport coat. The girl stood smiling at the barking dogs. Mrs. Christner noticed that she had very pretty teeth.

“Hello,” said Mrs. Christner through the screen.

“Mrs. Christner,” said the girl, “Russ left this at my house and I brought it home.”

“How nice,” said Mrs. Christner. “Thank you.”

Mrs. Christner recognized the coat. It was just like the blue velvet dinner jacket that her grandson often wore. She reached down, unlocked the screen door, and opened it.

Suddenly the girl pushed the screen door back with her elbow and forced her way in. “Step back and face the back door,” the girl ordered. Mrs. Christner saw that the girl held something under the coat. It looked like a gun, but she wasn’t sure; it really looked more like a hair curling iron; perhaps it was a gun with a silencer. She wasn’t sure.

Mrs. Christner turned around as ordered and faced the back door, visible from the foyer through the narrow connecting hallway. The girl, wearing thin white gloves, took a scarf, tied it around Mrs. Christner’s eyes, and sat her down in a chair in the foyer.

“Where are the switches for the front porch lights?” the girl asked. Mrs. Christner indicated they were next to the door. The girl moved away and Mrs. Christner presumed she was flicking the light switches. The girl asked if the burglar alarm was on.

“Of course not,” said Mrs. Christner. “The door is open.”

The Christner home was protected by a Rollins alarm system. The control box was located in the coat closet next to the front door. At night the alarm was set on red, full system; if a door was opened, the alarm was transmitted to a central security office. During the day, Mrs. Christner ordinarily set the alarm on the white button, the “sentinel” system. When a door was opened, a brief, high-pitched beep sounded, but no central alarm was transmitted to the security company. However, there were portable units placed around the house, including one attached high, but within arm’s reach, to the inside of the front door. If the button on one of these portable units was pushed, the full alarm system was activated. On this day, the alarm was set on the white button as usual.

Blindfolded, afraid, but alert, Mrs. Christner noted that the girl spoke with an accent, English or perhaps cultured Eastern. A minute or two passed and Mrs. Christner heard a man’s voice say, “Good work.” Pause. “Is there anyone else here?” Mrs. Christner replied, “No, I’m the only one here.” The girl then grabbed Mrs. Christner roughly by the arm, moved her to the living room, and sat her down in an armchair. “Now,” said the man, “we want your Fabergé and your jewelry.” His voice was gentle, ordinary; Mrs. Christner couldn’t note any distinguishing accent. “The Fabergé,” she replied, “is in the cabinets and the jewelry is in the secretary.” The secretary was a large antique desk in the corner of the living room. She heard the intruders go to work. When they spoke to each other, they used single initials; the man called the woman “C” and she called him “A.” “C” asked “A” if he had on gloves. “You know I have,” he replied.

“Where is the rest of the jewelry?” the man asked.

“In the bank vault,” Mrs. Christner replied.

“Don’t lie to me.”

“I’m not lying.”

Mrs. Christner knew that one of the portable burglar alarms rested on the table next to her, perhaps an arm’s length away. But she wasn’t about to make a move for it.

“What about this silver?” the girl asked.

“We could melt it down, huh?” the man said.

“Not this silver,” the girl replied. “You wouldn’t want to melt this down.”

“We don’t have anything to carry it in.”

“We can use these,” the girl said.

Mrs. Christner remembered that an antiques associate had recently brought over some art books in two large satchels. They were sitting, empty, on the living room floor. The thieves went to work loading the silver.

“Do you know my grandson Russ?” Mrs. Christner asked, wondering about the coat.

“No,” said the girl. “But we have friends who do.”

The female thief approached the blindfolded woman and removed a diamond ring from her hand. Mrs. Christner recalled gratefully that earlier in the day, when she had washed her hair, she had taken off the large ruby ring she usually wore, put it in a drawer, and forgotten to put it back on. “Please don’t take my wedding band,” she implored. “Leave it alone,” the male thief said. The female then moved to the hall closet. “Look at the fur coats,” she said. “Leave them alone,” the male replied.

The girl returned from the closet with a long, long piece of dark velvet that Mrs. Christner’s son, Russell, used in displays at the automobile show. The girl said she didn’t want to leave her scarf and tied the velvet strip in an additional blindfold, then removed the scarf from underneath. With the remaining length of velvet, the girl tied Mrs. Christner’s wrists and then stooped and began tying her ankles. “Don’t tie her too tight,” the man said. “For her circulation.”

When her ankles were bound, the man leaned over. “Now, Mrs. Christner,” he said, “we haven’t hurt you. But we will. If you call the police, the others will kill you.”

There was a brief commotion. Buttons, one of the Yorkies, bit the girl on the ankle. “The little bastard bit me,” she yelled and kicked at the dog. Buttons yelped. “Don’t do that,” Mrs. Christner said. “He’s just trying to protect me.”

The man then said he would go get the car and went out the back door. A few minutes later, Mrs. Christner heard the girl walk into the foyer; she removed a fur coat from the closet, and walked down the hall. Mrs. Christner heard the back door close. The whole episode had taken fifteen or twenty minutes. Mrs. Christner sat bound and blindfolded in the chair. She began crying.

After struggling with her bindings for five or ten minutes, Mrs. Christner managed to free herself and, still trailing the length of velvet behind her, walked immediately into the study and picked up the telephone. She called her son, Russell. Russell’s wife, Carol, answered the phone and began talking about Sunday school that morning. “Carol,” said Mrs. Christner, “I’ve been robbed. Get Russell.” After a brief conversation, Russell was on his way to the house.

A short time later Russell burst through the back door of the house, carrying his gun. “Russell,” said Mrs. Christner, “don’t call the police.”

“Don’t be stupid,” said Russell. He went to the phone and dialed the Highland Park Police Department.

Henry Gardner, the Chief of Police of Highland Park, had spent Sunday, September 24, at Texas Stadium watching the Cowboys beat the St. Louis Cardinals. He returned home about 6 o’clock that evening and shortly thereafter received a phone call from the station. There had been a robbery, a big robbery. Silver, jewelry, something called Faberge – it amounted to a heist in the million-dollar range. The Chief had better get down to the station.

Henry Gardner is a tall, bespectacled gentleman with graying hair; in his daily “uniform” of conservative suit and tie, he looks as much like an accountant as a police officer. A member of the Highland Park Police Department for almost 30 years, he has, not surprisingly, a solid reputation in the community. Like any small town police chief, especially in a town as well-heeled as Highland Park, he knows his territory intimately – who lives where, what they do for a living, who their kids are. He doesn’t know everybody in Highland Park, but he knows as much about the local citizenry as anyone.

This name Christner, though, was not familiar to him. He vaguely recalled the Lakeside home the officer had described to him, but he’d never had any dealings with this Mrs. Christner before. He didn’t know what this “Fabergé” business was all about – his first impression was of a collection of rare perfume bottles – but if his officers were right about the million-dollar size of the robbery, he knew it was the biggest thing that had ever hit Highland Park. Before long he would learn that it was the largest single robbery in the history of Dallas County and, as far as he could determine, one of the largest residential robberies in the annals of American crime.

Chief Gardner met at the station with Sgt. M. N. Hardin, the Criminal Investigation Division officer who was on weekend duty. Hardin had been summoned to the scene of the crime by the first officers to arrive and had conducted preliminary interrogations. He filled the Chief in on the details of the robbery – the account that had been given him by Mrs. Christner when he had arrived at her home that afternoon. With the bare outline covered, Gardner, Hardin, and Asst. Chief Montgomery climbed in a squad car and headed for the Christner home. When they arrived, Mrs. Christner, her son Russell, her attorney Carl Skibell, and her insurance agent Bill Pegel were gathered in the living room.

There was general confusion. There was discussion of fingerprinting, but Mrs. Christner assured them the intruders had worn gloves and Gardner didn’t press the issue. The basic details of the robbery were discussed, but little more was accomplished.

After about 30 minutes, Gardner and his men left. There wasn’t much to go on. There was the girl’s English accent; there was the familiar sport coat. In any case of robbery in excess of $50,000, the FBI is notified as a matter of course, because of the tangential likelihood of interstate transport of stolen property – a federal crime. Sgt. Hardin had already notified the FBI that afternoon and Gardner knew that the investigation would be a tangled one. His people would have to do some digging. Hardin was a good man; and Gardner knew he would get Sgt. McDonald in on this case too.

Detective Sgt. Ernest Loyd McDonald, a ten-year veteran of the Highland Park Police Department, was off duty on the Sunday of the robbery and the following Monday. On Tuesday, he accompanied Chief Gardner on a return visit to the Christner home. McDonald’s imposing physical stature matches his hard-edged, no-nonsense, old-time-detective approach to law enforcement. He’s a detective who responds aggressively to the thrill of the hunt. Some of his peers would say his aggressive Sam Spade style can tend to be abrasive. But he thrives on his work and the Christner case ignited his interest from the beginning.

Gardner and McDonald reviewed the facts of the case as they stood. Chief Gardner had recalled that on the day of the robbery, Mrs. Christner’s account had included the statement that her granddaughter, Laurie Ann, had left the house prior to the robbery to play tennis at the Dallas Country Club where the Christners were members. Gardner, in a basic fact follow-up, had called Dallas Country Club. “I’m sorry,” he was told, “we don’t have a Mrs. John W. Christner in our membership.” Gardner was confused. Subsequent questioning of Laurie Ann indicated that she had instead gone to play racquetball at SMU. Mrs. Christner said that her memory had simply been mistaken as to tennis or racquet-ball and claimed she had never said she was a member of Dallas Country Club.

Also on his first visit to the Christner home on the day of the robbery, Gardner recalled asking Mrs. Christner if she knew of anyone else in Highland Park who collected Fabergé; if the robbers’ interest in Fabergé was as specific as Mrs. Christner’s account of the burglary indicated, they might well have been planning to strike again. Mrs. Christner mentioned the name of a Mr. Sigmund Mandell. Gardner said he would like to call Mr. Mandell; Mrs. Christner suggested that she call him herself and went to the phone. As Gardner watched, she called Mandell, explained to him the situation, and hung up. Chief Gardner remembered being impressed with the way Mrs. Christner handled the call.

The following week, Chief Gardner paid a visit to Sigmund Mandell to talk about Fabergé and Mrs. Christner. Sig Mandell told him that, yes, he was slightly acquainted with Mrs. Christner, but that he had most definitely not received a phone call from her on the evening after the robbery. Gardner was stunned. Either he was very confused or Mrs. Christner was a very good liar.

Meanwhile, the most substantial lead in the case, the English accent and the sport-coat connection, had been tracked down. Russell, the grandson, had been questioned about any female acquaintances with an English accent. There was one, an English girl named Caroline Gibbons, a student at Surrey University who had been visiting her mother in Dallas during the summer.

Soon after the robbery, Mrs. Christner had assisted in making a composite drawing of the female thief. When a photograph of Caroline Gibbons was obtained from her mother, the Highland Park Police and the FBI were struck by the “remarkable similarities” between the composite drawing and the photograph. Caroline Gibbons was, for the moment, a significant suspect.

On the Friday following the robbery, FBI agent Jerry Hubbell and HPPD Sgt. Holcomb visited Mrs. Christner with a group of anonymous photographs of females, including the one of Caroline Gibbons, and asked her if any resembled the female robber she had seen. Mrs. Christner noted that one of the photographs (the one of Gibbons) looked more like the robber than the other photos, but that, no, it was not the same girl she had seen on her porch. Mrs. Christner also said that she had never met or seen her grandson’s friend, Caroline Gibbons. Then, through airline records and with the help of the FBI attache in London, it was verified that Caroline Gibbons had returned to her home in Kent, England, and, in fact, was riding horseback there on the day of the robbery. As to the sport coat, young Russ said that the blue velvet coat was in his closet at school in Alabama on the day that Mrs. Christner saw its double on her front porch.

On that same Friday visit with Mrs. Christner, Hubbell and Holcomb were about to leave when Mrs. Christner informed them that there was an additional loss in the robbery that she hadn’t reported before. She had discovered, they later recalled her saying, that some $40,000 in cash had been stolen from the small drawer in the antique secretary, the same drawer from which the thieves had taken the jewelry – $40,000 in tens and twenties. The investigators knew at once that $40,000 in bills of those denominations could not possibly fit in a drawer that small. When Gardner and McDonald were relayed that news, their ears pricked up. For the first time they discussed seriously their suspicions that maybe, just maybe, this robbery had not even happened.

Meanwhile Sgt. McDonald had been conducting an investigation into Janiece Christner’s background. It was his belief that in the case of a robbery such as this one, any and all information that could be gathered regarding a victim’s personal associations – friends, business acquaintances, relatives – might prove helpful in establishing new leads, new suspects, motives in the crime. But instead of shedding new light on the identity of the robbers, his investigation was casting new shadows over the identity of Mrs. Christner.

McDonald knew a few things about her. He knew that Mrs. Christner had been a resident of Dallas for some 20 years. He knew that she had been living in the Lakeside mansion since 1972. He knew that for some 25 years she had been married to John W. “Jack” Christner, a pilot for American Airlines; he knew that her husband had died of a heart attack in October of 1975 at the age of 67. He knew that she was a renowned collector of porcelain artifacts and silver. He knew that she had one son, Russell Christner, by a previous marriage, and that Russell had been adopted by her husband Jack. He knew that Russell, age 42, was the president of Christner Industries, a manufacturer of chemicals and car wash equipment. He knew that Russell had two children – Russell Jr. and Laurie Ann. He knew that Janiece Christner was reputed to be a woman of great wealth and distinguished Southern heritage. But beyond that, things got hazy.

It was her heritage that baffled McDonald most. In delving into Mrs. Christner’s past, McDonald found that nobody knew much about where she had come from. Different people claimed to have heard different things about her – and from her. One thing seemed to be agreed upon – she had been born and raised in South Carolina. But who was her family? Acquaintances were under the impression that she had a heritage of wealth – perhaps grand wealth.

More than one person thought he recalled the figure $50 million associated with her fortune. Some had heard that she was an heiress to the Coca-Cola fortune, that her family was the keeper of the original and priceless formula for Coke. Some had heard that she was one of the principal stockholders in American Airlines, or perhaps that her husband had been an original stockholder in the airline. Some had heard that her family was tied to the huge Burlington Mills fortune. Some had heard that her grandfather was one John Ash Burnett, a man of wealth and reputation in Charleston, South Carolina. As best Sgt. McDonald could determine, the original source for all this information must have been. Janiece Christner herself.

McDonald’s inquiry into records at the Bureau of Vital Statistics in South Carolina drew a different profile. It was McDonald’s determination that Mrs. Christner was born Thelma Janiece Sams in September of 1917 in Spartanburg, South Carolina; that her mother was one Lillie Davis Sams, age 29 at the time of her birth; that her father was one J.R. Sams, a millworker in Spartanburg, 40 at the time of her birth. It just didn’t figure. There were no signs of family wealth there. McDonald was further confused by the fact that Mrs. Christner’s driver’s license named her as Janiece Burnett Christner. McDonald and Gardner discussed their shared suspicions; they decided they would have to approach Mrs. Christner directly, to confront these discrepancies.

On Wednesday, October 11, Sgt. McDonald and Sgt. Hardin paid another visit to the Christner residence. Mrs. Christner greeted them and Sgt. Hardin wasted no time getting to the point. “Mrs. Christner,” he said, “we’re going to have to have some information on your family and friends.”

“I will not give you any information on my family,” she replied sternly. “They’re dead. They have nothing to do with this.” She changed the subject.

McDonald interrupted. “Mrs. Christner,” he warned, “we’re getting nowhere in this investigation. We will have to have information on your family background in order to continue.”

Mrs. Christner was visibly angry, livid in fact. “My parents did not come out of their graves to rob me,” she retorted. “My family has nothing to do with this robbery. You won’t get that information out of me.”

“You won’t give it?” McDonald asked.

“That’s right.”

“Well then, Mrs. Christner, in that case we have no choice but to tell the insurance investigators that you’re an uncooperative witness.”

Mrs. Christner glared.

“I’m going to find out who your mother and father are,” McDonald said. He turned abruptly and walked toward the door. As he left the house, Mrs. Christner thought she heard him say, “You’re gonna be real sorry.” (McDonald later denied this.) It was the last time there was any direct communication between Janiece Christner and the Highland Park Police Department.

In the wake of the robbery, Mrs. Christner and her attorneys filed insurance claims on the stolen property. A relatively small claim was filed with the Aetna Insurance Company on the basis of a general homeowner’s policy in the amount of $28,750 (the claim was subsequently paid without investigation). However, the major claim, in the amount of $857,875, was filed through the FTS Insurance Agency and the Freeway General Insurance Agency of Dallas, two local conduit agencies to Lloyd’s of London, the most prestigious insurance organization in the world. The total loss in stolen goods, as determined by Mrs. Christner and her attorneys, was $1.4 million, but some of the goods, mostly jewelry, were uninsured. The original Telex to Lloyd’s listed losses of $242,500 in fine arts, $206,200 in silver, and $382,000 in jewelry.

In the history of Lloyd’s of London, there had, of course, been many more substantial claims; but this one was, to say the least, significant. Within 24 hours of the report of claim, on the 28th of September, Harold Smith flew from New York to Dallas to check things out for Lloyd’s. Harold Smith is, technically, an independent insurance “adjustor”; in effect, though, he is an investigator, and has done many claims investigations for Lloyd’s.

Upon arrival at DFW airport, Harold Smith was met by William Pegel of the FTS Agency; Smith asked to be taken immediately to the Christner home. On the ride in from the airport, Pegel, the local agent who had first handled the Christner policy, gave Smith a brief profile of Mrs. Christner. Smith recalled Pegel indicating that she was a Coca-Cola heiress and that her father was a co-founder of American Airlines; she was, Pegel said, an extremely wealthy woman. Upon arrival at the house, Smith met with Mrs. Christner, her attorney Carl Skibell, her grandson Russ, and the maid Evelyn, to gather the basic facts regarding the robbery.

Later that afternoon, Smith met with Chief Gardner, Sgt. Hardin, and Sgt. McDonald; they informed him that they were having difficulties with some of the facts in the case. Smith was immediately intrigued with what he heard. He began a full-scale investigation and advised Lloyd’s that there were enough questions and enough points of confusion to delay payment on the claim.

Benefiting from the investigation of the Highland Park Police Department, Harold Smith continued his search into all facets of the robbery, and also began looking into Mrs. Christner’s renowned collection – and confronted new questions.

Mrs. Christner’s collection, the investigators soon learned, had been built with borrowed money. Back in the Forties, she had become interested in antiques. Her husband was in the Air Force; they moved around a lot; the young Janiece spent much time alone in new towns. She entertained herself by wandering through small antique shops, mostly looking, occasionally buying. But it was just a hobby, really, and remained so for many years.

But early in the Sixties, Janiece Christner had begun to develop a more specific interest in the refined world of antique porcelain, an interest that grew into a passion. She entered into a massive self-education program on the subject of Continental porcelain, scouring every reference work and talking to every expert she could find. Her fascination with the delicate figurines and richly ornamented tableware grew into a consuming desire to collect them, and ultimately evolved into a grand plan to establish the finest collection of Continental porcelain in the world.

But to establish such a collection required money, more money than she had. She began discussing her passion and her plan with loan officers at Oak Cliff Savings and Loan, a young and growing outfit with some innovative ideas in the area of investment loans.

Fine arts loans were not a common practice outside of some of the more aggressive banking institutions in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago. But it was an area of growing interest for lenders, and Mrs. Christner and Oak Cliff Savings decided that such an endeavor could be mutually beneficial. If Mrs. Christner could provide collateral – for example, jewelry to be held by the bank as a possessory pledge – she could then use the loans to purchase the porcelain objects of her desire. The steadily appreciating value of the artifacts would ensure her ultimate ability to repay the loans and the interest; her expertise in the field would guarantee sound purchases in the volatile market of fine antiques. The first notes were signed and the Christner Collection flourished. Mrs. Christner was described by her loan officers as “an excellent account.”

By the time of the robbery, Janiece Christner had indeed established one of the finest porcelain collections in the world. She had also accumulated a debt of five and a half million dollars to what had become First Texas Savings and Loan, a major multi-branch lending institution. Still, Mrs. Christner had maintained her “excellent account” status, apparently never becoming delinquent in her payments, which had reached as much as $60,000 a month. The bank, it seemed, had remained satisfied with the collateral and the appraised value of the collection.

Mrs. Christner’s closest artistic advisor in the process of gathering her collection was Mr. Charles L. “Carl” Wright. Carl Wright was one of the most respected men in the Dallas antique world; he had worked for Neiman-Marcus for years, and later owned a shop in the Quadrangle. His area of expertise was porcelain; early in her pursuit of a fine collection, Mrs. Christner sought his advice. A professional relationship developed. They traveled the world together in search of fine antiques, they studied together and traded opinions, and Carl Wright became a regular visitor in the Christner household.

After closing his shop, Wright continued to work as an art appraiser. For buyers and sellers, for insurance policies, for estate settlements, an appraiser is consulted to evaluate pieces of art. Carl Wright was considered one of the best in this part of the country, particularly in the area of porcelains; Mrs. Christner used his appraisal services regularly.

Because of his close and longstanding relationship with Mrs. Christner, Wright, now 80 years old but robust physically and acute mentally, became a central figure in the robbery case. Not only had he been the chief appraiser in establishing the values for the Lloyd’s insurance policy, but he had also done many appraisals to establish collateral values in Mrs. Christner’s bank loans.

Because of the massive number of appraisals he has done for Mrs. Christner over the years, Carl Wright suffers some confusion in reviewing them. But he recalls that some weeks after the robbery, two loan officers of First Texas Savings visited him at his apartment with Xeroxed copies of appraisals taken from the bank’s records; all bore Carl Wright’s signature. Wright was asked to examine them. The copies were not very clear, but in studying one of the sheets, Wright became distressed – the appraisal bore his name, but, he said, it was not his signature. Then, on the last sheet, Wright found two items listed as paintings by Renoir, one valued in excess of $200,000, another in excess of $400,000. The sheet again bore Carl Wright’s handwritten name. “My God,” he said, “this isn’t mine. She has no Renoirs.” He looked up at his visitors from the bank. They looked horrified.

Wright was later stunned to see his signature on a group of appraisals for insurance purposes, in which the last item was described as “an extremely fine painting by Renoir,” valued at $250,000; the description was of a painting Wright recognized – he had sold it to her for $3000 and it was not a Renoir.

On another occasion, FBI investigators visited Wright with a stack of appraisals secured from the records of First Texas; they were seeking his verification. Most of the appraisals appeared to be in order; but again, one discrepancy staggered him. Attached to one sheet was a picture of a painting with the attached notice that it was by Rembrandt and valued at one million dollars. Wright was sure she had no Rembrandts. This, he told the FBI, didn’t make any sense. His confusion was magnified by a document in the Texas Secretary of State’s office, a security agreement noting “Additional collateral: 1 original Rembrandt oil painting – subject of painting is a portrait of Rembrandt’s son Titus”; the document is signed by Janiece Christner, and dated December 2, 1977. Rembrandt’s renowned Titus’ Son was sold in a memorable auction several years ago and hangs in a museum in California.

Meanwhile, Harold Smith had turned up appraisals of Mrs. Christner’s jewelry that bore the name of Sotheby Parke Bernet Inc., the famed art auction house of London and New York. The signature was that of Dennis Scioli, one of SPB’s New York appraisers; the appraisals were from the Lloyd’s files and had been submitted “for the purposes of insurance.” There were several sheets stapled together; it was apparent even to the untrained eye that different sheets were different in style, produced by different typewriters. A few of the sheets were professionally correct; others were marred by misspellings and typos. Upon questioning, Scioli said that some of the sheets appeared to be legitimate Sotheby Parke Bernet documents; others did not. Furthermore, he said, the handwritten name appearing on one of the sheets was not his signature.

The mounting suspicions, even early in the investigation, had had direct repercussions on First Texas Savings and Loan. At the time of the robbery, First Texas and its holding company. First Texas Financial Corporation, were about to be bought by Beneficial Finance, a Delaware financial conglomerate. Negotiations had been underway for months and final sale was pending approval by the Federal Home Loan Bank Board.

The robbery, with the attendant shadows cast on Mrs. Christner and on her collection by the investigations and subsequent discrepancies and rumors (whether well-founded or not), was a potential bombshell. Reportedly, there was immense concern on the part of First Texas that the incident might blow the Beneficial deal entirely.

First Texas decided that there would have to be a reckoning with Mrs. Christner; her loans must be called in. And, at about the same time, two of the bank officers who had worked most closely with the Christner account in recent years resigned their positions.

After much legal negotiation between First Texas and Mrs. Christner and her attorneys, an agreement was reached. Mrs. Christner would be forced to sell a substantial portion of her collection, in fact almost all of it, at auction; a large percentage of the proceeds from the sale would go to First Texas for the purposes of reducing the existing debt toward the ultimate retirement of the loan. Janiece Christner’s collection would be broken up. She was shattered at the prospect, but she had no choice.

Carl Skfbell, Mrs. Christner’s attorney for a good many years, had become frustrated by the procession of events in his client’s case. Skibell, a friendly, assertive, 45-year-old civil attorney, had tried to cooperate with the various investigators who had become involved; but communications with the Highland Park Police had reached an impasse following an incident a few weeks after the robbery. Laurie Ann Christner had been approached at her dormitory at TCU by a man who, she said, identified himself as an FBI agent; he asked her to sit in his car and answer some questions. When Mrs. Christner was informed of the episode, she queried the FBI, who said they had not sent an agent to talk to Laurie Ann. The Highland Park Police said that yes, one of their men had interrogated Laurie Ann; but the officer would not have represented himself as an FBI agent; why would he? But Mrs. Christner was furious about the apparent subterfuge. From her point of view, the Highland Park Police had established an adversary relationship.

On December 6, Skibell filed a sworn proof of loss as a matter of required procedure in the Lloyd’s insurance claim. By the same procedure, the insurance company must respond within within 90 days. Over those 90 days, Skibell was, of course, aware of the various investigations by the FBI, by Harold Smith, by the Highland Park Police Department. He could only guess at their general suspicions and what they were hoping to prove. But after 90 days, he had received no direct legal response from Lloyd’s. So, on March 9, Skibell, on behalf of Mrs. Christner, filed a lawsuit in Dallas County 14th Judicial District Court citing the Underwriters at Lloyd’s of London with failure to pay the sum of $857,875 as due under the terms of the policies of insurance, plus interest on that amount, plus attorney’s fees. In essence, they were demanding that Lloyd’s pay up – in the amount of nearly one million dollars.

In response, Lloyd’s, through Dallas attorney Larry Anderson, filed a general denial. On April 13, Skibell filed a motion for summary judgment. A motion for summary judgment is a request for a hearing before the court to examine the existing evidence, to determine if there is any genuine issue of material fact. In effect, it is an effort to procure a favorable decision from the judge without a trial. Skibell was forcing the issue.

The position of the plaintiff, Mrs. Christner, was simply that she had legitimate insurance policies, that she had suffered a loss by robbery, and that she should therefore be paid the sum of $857,875.

On May 17, Larry Anderson, on behalf of Lloyd’s, filed the defendant’s reply in opposition to the motion for summary judgment. The wording was blunt: “That in truth and in fact a robbery did not occur at the Plaintiff’s residence … but that she merely claimed to have a robbery in order to recover for insurance purposes to help repay her bank debt of Five Million Dollars.” Furthermore, “that the Plaintiff, in connection with the procurement of said policies, made material representations to the Defendant . . . and said policies would not have been issued had the Defendant known that such representations were false and fraudulent.” The response then went on to cite her claims to be an heiress, to be a stockholder in American Airlines, Coca Cola, and Burlington Mills, and to be a relation of John Ash Burnett, “when in truth and in fact none of these representations were true and she was merely the widow of an American Airlines pilot and had borrowed money from the First Texas Savings and Loan Association . . . with which to amass a large amount of jewelry and fine arts.” Also cited were “substitute” and “fraudulent ” appraisals.

Most interestingly, attached were two affidavits, one signed by Chief Henry Gardner and one signed by Sgt. Ernest Loyd McDonald (Sgt. Hardin, the original Highland Park Police investigator, died of a coronary in March). These sworn affidavits were filed in support of the allegation that no burglary had occurred. The affidavits, both very similar, brought forth all of the suspicions of the Highland Park Police: Each included a list of 14 reasons as to why it was their “professional opinion that the robbery did not occur:

1. That the thieves allegedly remainedin the front room of the house andentered by the front door.

2. That the thieves did no house searchwhatsoever, but merely relied upon herstatement that no one else was present.

3. That the thieves did not bring alongtape or rope to tie up the victim.

4. That the thieves allowed her to sitnext to a burglar alarm switch.

5. There was no physical evidence ofabuse.

6. That the thieves did not knowwhether or not there were any other occupants or maids in the house, and therewere cars in the driveway.

7. It was a Sunday afternoon whenthere was much traffic on Lakeside Drivein Highland Park, Texas.

8. That the robbery was reported approximately one hour after it occurred.

9. That the burglar alarm system wasturned off.

10. That none of the police informantswho would know about robberies of thisnature knew anything about said robbery.

11. That although the items stolen wereunique and one of a kind in the world,there has been no evidence of their everturning up, or attempts for ransom.

12. That Mrs. Christner refused to cooperate with the police investigation.

13. The thieves never inquired about asafe or searched the bedroom which is themost logical place in a home forvaluables.

14. That Mrs. Christner lied to the PoliceDepartment in that she represented that Forty Thousand Dollars in cash hadoriginally been stolen; that she misrepresented the whereabouts of her granddaughter, Laurie Ann Christner, atthe time of the robbery; that she misrepresented the fact that she made acall to Sigmund Mandell (which he subsequently denied); and the mattershereinabove set forth concerning thevarious appraisals, her heritage and thevarious misrepresentations on bankloans.”

In the days that followed, the legal game intensified; depositions were taken from almost everyone attached to the case, on both sides, all in preparation for the summary judgment hearing scheduled for mid-July. Not only did things heat up legally, but emotionally as well, culminating in a curious incident on the evening of June 7.

Months before, Mrs. Christner had been approached by a private investigator named Thomas E. Boiling, who suggested in a letter that he might be of help in recovering the stolen property. He was subsequently hired; “I was hired basically,” he explained in a statement-later, “to investigate Det. Sgt. Ernest Loyd McDonald of the Highland Park Police Department as to his background and any illegal or unethical acts he may have committed.”

On June 7, Boiling, who happened to be a former Highland Park police officer, was with his brother on Edmondson Drive in Highland Park. They were, according to Boiling, seeking a house where a burglary had occurred months before; they had knocked on a few doors and questioned a few people in the process. A Highland Park patrol car pulled up; the patrolmen checked the men’s ID, asked what they were doing, radioed the station, and then told Boiling to follow them to the station. Boiling refused. He and his brother were arrested, taken to the station, and put in jail.

Eventually Boiling was questioned by Gardner and McDonald and, according to Boiling’s statement, they “began using obscene language, insulting me, and asking questions about my client.” He said both threatened to kill him if he came near their homes or families. Boiling was told he was being arrested for “terroristic threats, soliciting without a permit, and interfering with a police investigation,” among other charges, and that he might be arraigned in the morning. He was again locked up, but was released the next morning without further explanation. Boiling subsequently filed an allegation with the FBI charging civil rights violations.

Meanwhile, through the turmoil, Janiece Christner was readying her beloved collection for auction. Arrangements had been made to hold the auction at Christie’s in New York on June 7, 8, and 9. An auction of this magnitude – for it was indeed an extraordinary collection and an important sale – was a major event in the art world. Certainly it was a major event, and a major source of revenue, in the eyes of the world’s two largest auction houses, Christie’s and Sotheby Parke Bernet. Mrs. Christner had finally selected Christie’s, she said, because of her long association with the house’s European porcelain expert Theodore Beckhardt; it seemed likely too that Sotheby Parke Bernet’s legal entanglements (due to the Scioli appraisals) also contributed to the decision. At any rate, some bad feelings passed between the rival art houses regarding the Christner Collection. But Christie’s won out.

On the Tuesday night before the auction, Christie’s held an elegant reception in honor of the collection and, of course, of Mrs. Christner. Collectors and dealers from around the world had gathered; the displayed collection shimmered throughout the halls and galleries of Christie’s. But, a few hours before the reception, Mrs. Christner called; she was 3000 miles away, she said, and wouldn’t be there for the occasion. Christie’s officials were stunned and insisted that she at least be present for the auction. Mrs. Christner was never seen at the auction; however, she flew to New York and stayed in contact with Christie’s by telephone from her suite at the Hotel Pierre. She had decided that, with the swirling publicity resulting from her legal problems, she would stay out of the limelight. What might have been her finest public hour, the culmination of a dream, was spent alone, in hiding.

Christie’s officials were all too aware of the legal problems attached to the Christner Collection and were somewhat fearful that the negative publicity might hurt the auction. They made a solid public relations effort to counteract it, careful to note to all who inquired that every item had, of course, been thoroughly examined for authenticity (though, they maintained, there had never really been any question) and that First Texas Savings had released all liens against the collection for the purpose of sale (after all, they were the ones who would benefit most from the auction), assuring that all buyers would get clear title. The campaign was successful; most of the buyers in attendance claimed that Mrs. Christner’s personal problems had nothing to do with the collection as far as they were concerned.

Thursday, the first day of auction, was given over to the sale of silver. Many items went for prices higher than anticipated; only two lots out of 105 failed to sell – an extraordinary figure. The total take was more than three-quarters of a million dollars. The officials at Christie’s were ecstatic.

The next two days of the auction, the porcelain sales, were less dramatic, in fact somewhat disappointing. Some observers attributed it to the fact that much of the porcelain had been recently bought; too little time had passed since last sale to enhance values. Some $521,000 worth of porcelain was auctioned in two days, raising the total proceeds from the three-day auction to $1.4 million. Impressive, but hardly enough to square things between Mrs. Christner and her bank. However the auction had not included the entire collection – perhaps half. The remainder would be auctioned later, in October. Also, a separate sale of Mrs. Christner’s jewelry would be held. Still, on the bottom line, it didn’t seem likely that the bank would get all its money back.

Back in Dallas, the legal parade marched on, headed for a July 19 hearing on summary judgment. The curiosities of the case were heightened again when it was learned just where Mrs. Christner had been on the evening of Christie’s reception; she’d been in Los Angeles, where, in conjunction with the FBI in California, she had followed up on an informant’s phone call and assisted in the recovery of two of the stolen items. Still, the implications of the recovery were unclear.

As might have been predicted, the July 19 hearing was postponed, at the request of Lloyd’s attorneys, until September. And the October auction was postponed until December. The shadows on the Christner case were lengthening.

Then, on August 1, Carl Skibell dropped a bombshell. He filed, on behalf of Mrs. Christner, a new series of pleadings, an amended original petition. It began with a charge that amounted to a direct challenge of Lloyd’s and its modus operandi, charging that “secret syndicates contracted to underwrite and subscribe to the insurance policies issued to the Plaintiff under the name Lloyd’s Policy . . . The Defendants are various individuals whose names and identities are unknown to the Plaintiff but who transact business secretly and surreptitiously under various assumed names and under secret code numbers.” Thus, the petition went on to say, the “Defendant made statements and committed acts in reference to the above described policies of insurance issued by Defendant to Plaintiff which constitute false, misleading, and deceptive statements and acts under the Consumer Protection Act.”

Then, on another front entirely, but in the same petition, it was charged that the “Plaintiff, as a free and independent citizen, had the right to be free from unwarranted appropriation or exploitation of her personality and the publicizing of her private affairs, with which the public and the Defendants had no legitimate concern . . . Plaintiff states that the scope and character of the investigations conducted by the Defendants and the agents controlled by the Defendants and each of them, exhibited ill will and evil motives, gross indifferences to Plaintiff’s rights and as such were willful and wanton acts done without reasonable cause or excuse . . . The Defendants’ agents, in the course of their investigation . . . authorized their agents, attorneys and employees to publish, declare and by other devious methods to disseminate false, inaccurate and misleading information intended to discredit Plaintiff in the antique industry, and to the public and likewise intended to hold her out to ridicule to the antique industry and the public. These actions were done as part of a premeditated plan to benefit the Defendants in seeking to defeat Plaintiff’s claim . . . (by) causing an investigation of the Plaintiff and her family and fostering untruthful and malicious slanders and libels of the Plaintiff with respect to her background, her children’s background, her credit, her reputation for paying her debts, and attacking the credibility and quality of the antiques in her collection of fine arts . . . Plaintiff states that she has suffered actual and exemplary damages for the invasion of her privacy . . . and that in truth and in fact said actions did damage the Plaintiff by destroying the value of her collection at the auction sale . held in New York City . . . thereby causing Plaintiff to suffer severe losses, endure great humiliation, shame, embarrassment, mental pain and anguish to her damage in the sum of Seven Million Dollars … In the further alternative . . . Plaintiff says that as the acts of the Defendants were willful and malicious and designed to harm and destroy Plaintiff, the Defendants should be held liable for exemplary or punitive damages in the amount of an additional Fifteen Million Dollars.

In effect, Janiece Christner had escalated her lawsuit by a staggering 22 million dollars.

The Christner case has become almost impossibly entangled. With all of the charges and counter charges, allegations and implications, in-nuendos and rumors, facts and fictions; with the stacks and stacks of motions and depositions, financial records and appraisals, affidavits and exhibits; and with the still-snowballing civil litigation and the still-pending possibilities of criminal prosecution, it will take many months, maybe years, to unravel the huge legal knot. It will likely be a long time before any realistic conclusion is reached as to what the truth of this matter is.

But as the case stands now, the knot has been tied with four major strands. It has, in its simplest reduction, four sides: Side 1 is Lloyds of London; Side 2 is the Highland Park Police; Side 3 is Janiece Christner; Side 4 is the FBI. When each side’s story is told separately, it helps reduce the chaos.

The Lloyd’s of London side of the story is the most easily understood. Lloyd’s is legally referred to as “Lloyd’s of London (Not Incorporated).” It is not a “company;” it is a building where independent insurance brokers gather to form syndicated coalitions which arrange specific policies for coverage of specific needs. Because of this share-the-risk-share-the-wealth arrangement, it has allowed aggressive and innovative brokers to provide insurance coverage in unusual areas or on enormous values that regular insurance companies ordinarily would not handle. Because of some of the exotic forms of coverage, Lloyd’s has earned a reputation: If Lloyd’s of London won’t insure it, nobody will.

According to an English fine arts dealer, however, it is said in the art community that Lloyd’s of London will insure anything, but will pay nothing. His implication is that Lloyd’s will readily underwrite valuable artifacts, but when a claim is made, the matter of collecting can be a slow and tedious process. And often it winds up in the courtroom; the computer printout of lawsuits pending against Lloyd’s of London in Dallas County alone is over six feet long. For Lloyd’s it is simply a matter of sound business practice to investigate major claims to be sure they are obliged to pay, even if it means a legal battle.

When Harold Smith arrived in Dallas to investigate the $857,000 claim of Janiece Christner, he walked into a ready-made situation. Within 24 hours he had been handed enough discrepancies to fuel a full investigation, and certainly enough suspicion to justify a delay of payment until some questions could be answered. The Highland Park Police had already done much of his work for him: They had raised the very strong suspicion that a robbery had not occurred. If not, Lloyd’s obviously had no obligation to pay. Because Harold Smith’s business is to save Lloyd’s money, he would have been foolish not to ally himself, and Lloyd’s, with the suspicions of the Highland Park Police.

Lloyd’s position was then bolstered by Smith’s investigation of the Christner policy itself, turning up evidence that there was at least a strong possibility of tainted information supplied by the insured, and perhaps even of forgery and fraud. If Lloyd’s could, on legal grounds, save itself $857,000, it certainly would. From a legal point of view, Lloyd’s had no further interest in Mrs. Christner beyond settling the claim, preferably in their favor, and getting out. Any extended legal action against her would be of no benefit to them. For the purposes of tidying up their side of the situation, Lloyd’s attorney Larry Anderson tendered in court $45,000, her current premium on the policy, essentially a refund of her premium. “Otherwise,” says Anderson, “I’d be talking out of both sides of my mouth.”

Anderson, Harold Smith, and Lloyd’s, from the outset, had a lot going for them. Mostly what they had going for them was the Highland Park Police.

From the beginning, the Christner robbery just didn’t add up for Chief Gardner and Sgt. McDonald. More than anything else, they were annoyed by Janiece Christner’s attitude. If, as she said, she wanted more than anything else to get her beloved possessions back, why wasn’t she bending over backwards to assist the Highland Park Police with their investigation? They had explained the reasons for their probes into her past, and she had reacted strangely, as if they had crossed onto sacred ground – or as if she had something to hide. It was her blurred and unsubstantiated self-portrait as a woman of inherited wealth and sophisticated Southern upbringing that disturbed Gardner and McDonald most. They came to think of her as “the magnificent liar.” They felt she had lied about the Dallas Country Club; lied about Sig Mandell; lied about the $40,000 in the drawer. Their suspicions were only heightened when she later said that she had never claimed that $40,000 was in that drawer, but only $9000; and later that much of that cash had actually been in a different drawer and only $2000 had been in the small drawer. She had never “lied” directly to Gardner or McDonald regarding her past – their suspicions were rooted in what they understood others had said and in the statements reportedly contained in an intra-office memo at First Texas describing her as an heiress; but whenever they had broached the subject with her, she refused to clarify things for them. From their point of view, she simply wasn’t playing straight.

When the Lloyd’s suit was filed, and Mrs. Christner’s deposition was taken by Larry Anderson, the suspicions regarding her past were thrust into the legal limelight. What came forth only lent credence to Gardner’s and McDonald’s suspicions:

Q. (by Larry Anderson) I will ask you if your father’s name was J.R. Sams?

A. (by Mrs. Christner) No way, no sir.

Q. I will ask you if your mother’s name was Lillie Davis?

A. Was.

Q. Okay, what is your father’s name?

A. I prefer not to get into that.

Q. I am going to insist on it.

A. I’m sorry.

Q. You refuse to give it?

A. Yes.

Q. Do you have any brothers or sisters?

A. No. I have two half-sisters that were my mother’s children by her first marriage.

Q. By …

A. We have the same mother but not the same father.

Q. By Mr. Sams?

A. That’s their father.

Q. That’s their father?

A. Uh-huh. There were two girls and one boy.

Q. Including you.

A. No, not including me.

Q. So Mr. Atkins was your father?

A. No.

Q. What is the name on your birth certificate?

A. I think there was none on it for years until I went down to get a passport, and I had to take my mother with me, and she filled it out, and it was Thelma Janiece Sams, yes, but my father is not John Something Sams. I never saw him in my life. I think he was already dead when I was born. I don’t know.

Q. Well, are you related, in any way, to John Ash Burnett?

A. I prefer not to answer that.

Q. Do you know who John Ash Burnett is?

A. 1 do.

Q. Who is he?

A. I prefer not to answer that.

(Later)

Q. Do you own any stock in the CocaCola Company?

A. I do and I prefer not to get into it.

Q. How much stock do you own in Coca-Cola Company?

A. I prefer not to answer that.

Q. You refuse to answer?

A. I do.

Q. Have you ever represented that your family was one of the founders of the Coca-Cola Bottling Company?

A. Absolutely not, but I did buy the first stock that was ever issued.

Q. Your family did?

A. Yes.

Q. Or you?

A. No. I wasn’t born then.

Q. Are you referring to your mother?

A. No.

Q. Who are you referring to?

A. I prefer not to answer that.

Q. You refuse to answer?

A. I do.

Q. Do you – was your family one of the founders of the Burlington Mills?

A. Absolutely not. Wrong mill.

Q. Wrong mill?

A. Wrong mill.

Q. What mill were they founders of?

A. I prefer not to answer that.

Q. You refuse to answer?

A. I do.

Gardner and McDonald had decided that if she had lied about her family, she could lie about other things. When Harold Smith produced appraisals and Dennis Scioli determined that they were not authentic Sotheby Parke Bernet appraisals, Gardner and McDonald felt it fit Mrs. Christner’s deceptive puzzle. When First Texas produced appraisals that confused Carl Wright, Gardner and McDonald felt that fit the puzzle.

It came as no surprise to them that Mrs. Christner was a frequent visitor to the courtroom, that in fact, since 1960, she had filed at least six different damage suits (against Tom Thumb for injuries suffered when she slipped on produce juices, against Bekin’s Moving & Storage for a damaged vase, two suits against R.E.A. Express for a damaged chandelier and damaged porcelain, against a contractor regarding a remodeling project on her Lakeside home, and against actor Steve Forrest for breach of contract in connection with a proposed movie production). Gardner and McDonald felt it fit the puzzle.

But the crux of the issue was that Gardner and McDonald believed she had lied about the robbery – that it was a set-up, a phony. Too many little things didn’t make sense. Why would a wealthy woman keep her valuable jewelry in a desk in the living room? Why, when the first officers arrived at the scene of the crime, did the victim show no signs of being nervous or distraught? Why had the female thief asked the male thief if he was wearing gloves if she could see he was obviously wearing them? Why did Mrs. Christner submit to the Highland Park Police four different lists delineating the stolen property? For Gardner and McDonald, the little things added up to the big lie.

Furthermore, they felt she had good reason to fake the robbery, that she needed that insurance money. Gardner and McDonald had learned that during the summer prior to the robbery the IRS had raised some questions about taxes on her husband’s estate. The IRS, Gardner and McDonald learned, had made their inquiry known to First Texas; surely, thought Gardner and McDonald, First Texas had become squeamish – after all, she owed them over $5 million. And, since Gardner and McDonald were under the impression that Mrs. Christner had no source of income other than her bank loans, what better way to get some quick cash than to stage a robbery and collect the insurance money? The two men were convinced she was a con artist, a very accomplished con artist. To them the total picture was clear. The woman had come from an obscure background and set herself up as a wealthy heiress. She duped a bank’s loan officers into believing her tales of wealth and into helping her finance her porcelain dream. Everybody got in over his head. When her house of cards began to topple, she needed to do something fast, so she faked the robbery. A first-rate con artist, thought Gardner and McDonald.

In May, Larry Anderson, on behalf of Lloyd’s, made a motion to take the deposition of the head medical librarian at Timberlawn Psychiatric Hospital. It was a sudden and curious development in the case, but it was more than just a legal fishing expedition. Anderson had received a tip from an attorney who had been involved in Mrs. Christner’s 1960 lawsuit against Tom Thumb. “I have a distinct recollection,” that attorney says, “of evidence presented in that case that Mrs. Christner had undergone evaluation at Timberlawn some time prior to that case and that the diagnosis was that of a pathological liar.” The trial transcripts in the case no longer exist in the County records, having been routinely disposed of years ago. Anderson’s motion was an attempt to secure the significant medical records, if they existed. But Carl Skibell reacted immediately and filed a Motion to Quash the taking of the deposition; Judge Fred Harless ruled in Skibell’s favor on the basis of a privileged information statute, ordering that the deposition be stayed and not taken until further orders from the Court.

Still, to all close observers in the case, the proposed inquiry raised significant new questions in the case. What is a pathological liar? The definition is significant in that the term has been bandied about in this case; in fact, in a subsequent interview, Mrs. Christner labeled Sgt. McDonald a pathological liar. In the consideration of many psychiatrists, the “pathological liar,” though not a conventional or technically official psychiatric term or diagnosis, is considered by many psychiatrists to be the key psychiatric element in the mentality of the so-called “con artist.”

Dr. John Holbrook of Dallas is a forensic psychiatrist who has done extensive research into the pathology of the con artist. He describes the psychopathic con artist as “a personality that is more than just a personality; it becomes a lifestyle with the individual. The whole lifestyle is geared to obtaining what he wants through a series of fabrications. He enjoys the deception and the reaping of profit from it. The individual displays no guilt, no anxiety. He is, however, always aware that he is lying – he just doesn’t have the usual values that apply to lying.

“He views the lying as a necessary ingredient to power. It becomes the central theme of his life; without it he becomes restless, petulant, depressed, accusing. He blames everybody else for things that go wrong and antagonizes his accusers – he is, in his own mind, always right and can rationalize anything to displace the blame or guilt. He never shares his condition with others; he has few friends, few close relationships, is essentially a loner. But those closest to him in fact become the most vulnerable because they want to believe him.

“It is a self-destructive course, but the individual never contemplates failure, never anticipates being caught. He is 100 percent convinced he will prevail. He is always in command; always displays a sense of confidence. If caught, he often responds with denial. He will only make admission if it is self-serving. In fact, the personality is totally perdictable: He is always self-serving and always ego-enhancing. He never deviates from that -ever.”

The Timberlawn records of Janiece Christner may or may not exist, and psychiatric supposition may or may not have relevant value in this case. But in the minds of Chief Gardner and Sgt. McDonald, the episode, once again, fit the puzzle. On the strength of their convictions, they had turned their efforts away from a search to find the robbers, who, they believed, didn’t exist; their efforts were aimed instead at Mrs. Christner. They had become frustrated with the lack of speed with which the FBI was pursuing the case. Gardner and McDonald were convinced there was enough to go on, enough to take to the Grand Jury, to bring this woman to justice. Why, they wondered, wasn’t the FBI seeking an indictment on this woman already – at least on the grounds of bank fraud? They were aware of the fact that discussions had taken place between First Texas and the U.S. District Attorney’s office, where it would be decided whether a case would be presented to the Grand Jury; a solid case would require a complainant, which would, of course, be First Texas. It seemed evident that the bank had chosen to settle with Mrs. Christner privately, outside of the courtroom – perhaps to avoid any additional negative publicity. But Gardner and McDonald remained steadfast in their own conviction; eventually, they thought, they would get her. They still believe their truth will out. They still firmly believe they are right.

Carl Skibell, Mrs. Christner’s attorney, shakes his head in amazement. “What this is,” he says, “is a simple civil lawsuit that has been blown completely out of proportion.” From his point of view, the Christner case began simply as an insurance claim. When the claim was not paid, a lawsuit was filed, followed by a motion for summary judgment. “At that stage,” says Skibell, “we needed only to prove two points. One, that there was in fact a robbery. And two, that Mrs. Christner held an ’agreed value’ policy with Lloyd’s and the premiums had been paid.”

Point two, says Skibell, has become extraordinarily confused because the whole business of art appraisals is so confusing. An art object, any object, can be appraised in different ways. The art object can be appraised at auction value – what the item can reasonably be expected to bring at auction. It can be appraised at resale value – what a competent dealer will ask and obtain from an assumed intelligent buyer. It can be appraised at replacement value – the price at which the item may reasonably be replaced within a reasonable time. It can be appraised at market value – what a willing buyer will pay a willing seller on the open market. The range of difference is often considerable. Any art appraiser is usually aware of his client’s purpose in obtaining an evaluation. For example, if it were being appraised for purposes of estate settlement, it would be valued low to reduce tax consequences. If it were being appraised for sale, it would be appraised high to benefit the seller. If it were being appraised for insurance purposes, it might be valued low to reduce premiums. If it were being appraised as collateral for a bank loan, it would be valued higher to maximize the amount of loan. In other words, there is no “real” value.

It is Carl Skibell’s contention that the Lloyd’s policy was established on “agreed values” – acceptable to both the insured and the insurer. It is also his contention, in reaction to the general intimations of fraud that have been raised, that the alleged discrepancies can, to a large extent, be explained by the confusion of the various kinds of appraisals that have surfaced. And that the massive paper flow in regard to both her insurance policy and bank loans could easily result in discrepancy and confusion. “Anyone,” Skibell explains, “could staple together a group of appraisals that weren’t intended to go together; any clerk could, in error, type out the wrong group of appraisals. It’s such an intangible business that confusion is to be expected. And there are legitimate explanations for all of the allegations that have been raised regarding the appraisals. I can’t try my case in your magazine, but it will all be explained in court.”

As to the robbery, Skibell is equally confident. He believes in his client’s innocence every bit as strongly as the Highland Park Police believe in her guilt. He has, in fact, developed a sense of outrage as to the way the case has been handled and his client has been treated. “The most significant aspect of this case,” Skibell says, “is the suddenness with which the Highland Park Police made up their minds as to what had happened, how quickly the victim, Mrs. Christner, became the suspect. As an example, only two days after the robbery, when Sgt. McDonald first interrogated Mrs. Christner, he mentioned to Mrs. Christner that, some months before, there had been a burglary of one of Mrs. Christner’s neighbors, whom he named. The burglary was unsolved, but Sgt. McDonald suggested to Mrs. Christner that it had been a set-up, staged by the victim. I found those comments alarming on two counts. In the first place, he was already intimating suspicions of Mrs. Christner – he was suspicious of her before he had even begun an investigation. And secondly he was recklessly talking about another case, confidential information, naming names, and making accusations, a totally unprofessional action on the part of a police officer. And I immediately complained to Chief Gardner. I was concerned from the start about the scope and nature of their inquiry.

“What’s worse is that their suspicions have evolved into a personal vendetta. What does Mrs. Christner’s private life, her family history, have to do with this case? Nothing. She had every right to refuse to discuss those matters. It should certainly be the initial purpose of the police in this case to attempt to find the thieves and attempt to find and return the stolen property. But their investigation has never been aimed in that direction. For reasons I honestly don’t understand, the Highland Park Police have, from the outset, aimed their investigation at Mrs. Christner instead. In my mind it raises serious philosophical questions about the abuse of power of police officials. They’ve made Highland Park into their own fiefdom. And this whole case smacks of small town cop syndrome.

“The most disturbing aspect of this personal vendetta,” Skibell continues, “happened when Chief Gardner and Sgt. McDonald chose to sign those affidavits in connection with the Lloyd’s case. I’ve never seen the police get involved in an insurance case. It’s unheard of for a police official to submit sworn affidavits in a civil suit; an astute police officer would never submit such an affidavit if a legitimate criminal suit were pending – it would lead to a conflict of interest. I also find it highly significant that they have now submitted new affidavits, changed from their original affidavits. The new ones, for example, no longer contain any mention of Sig Mandell. To introduce new and different affidavits seems highly unusual to me. Besides, if the Highland Park Police were so convinced they had a criminal case against Mrs. Christner, why did they instead choose to ally themselves with Lloyd’s in the civil suit? Because it was the only way they could get at her. It had become a personal thing. What it amounts to is persecution.”

It is that notion of persecution that has ultimately led to the $22-million damage suit filed by Mrs. Christner on the bases of “invasion of privacy,” “mental anguish,” “libel and slander.” Skibell admits that it is the full reflection of the fact that this case has gone utterly beyond its bounds. “But,” he says “the opposition chose to push this case into those areas – we have no choice but to fight back on those grounds.”

In December of 1978, after Skibell was made aware of the fact that Lloyd’s was conducting a “discreet investigation” of Mrs. Christner, he decided it would be prudent to bring a criminal attorney into the case to protect against future possibilities of criminal indictment. He approached Frank Wright, a Dallas criminal attorney of high reputation.

“My practice,” says Frank Wright, “has become a highly selective one. I chose to accept this case because, after reviewing the facts in the case, and particularly after hearing Mrs. Christner’s statements, my gut reaction was that she was telling the truth. There were minute details that, in my opinion, wouldn’t be made up. And I haven’t changed my mind. It’s a new situation for me. As a defense attorney, I enjoy the novelty of being in this position, of being able to be 100 percent candid, of not playing any defense attorney games, of actually demonstrating innocence. I’ve spent much of my time assisting the FBI in turning over all of Mrs. Christner’s records. I’ve never had a case before where I could sit down with the FBI and give them everything, where I could help the FBI to the benefit of my client. That’s normally a process alien to my practice.

“Let’s look at this case logically,” Wright continues. “In my mind, the best argument for the fact that there was a robbery is the fact that the worst thing she could have done would have been to fake a robbery. Mrs. Christner had developed what I consider, from a business standpoint, a master plan, a master plan that had worked. With legitimate loans from the bank she was able to buy fine arts and sell them at a profit – that’s what her business, Mrs. John W. Christner Antiques, Inc., was all about. At the same time, she was establishing her own valuable collection. In spite of the fact that her loan debt was of such magnitude, she had never missed a payment. In spite of allegations that she had no other source of income, her income tax returns for 1977 show that she had a gross income in excess of a million dollars – from her antique business, from Christner Industries, from stocks and bonds, various sources. At the time of the robbery, her financial status was solid and her bank was happy. Immediately after the robbery, she didn’t want to report it – her son did. She was fully aware of the magnitude of her account with First Texas and knew that a robbery and investigation might well send the bank into a panic. That it might even force a settlement of the loan, sale of the collection, and an end to the master plan. It seems to me she could have more easily swallowed the $800,000 loss and worked privately to recover the stolen property than risk that turmoil with the bank – which is ultimately what happened.

“The FBI has thoroughly reviewed her financial records and it’s my understanding that they have concluded there is no case for prosecution on the charge of bank fraud. Their investigation is continuing on the question of interstate transport of stolen goods, but, as far as my client is concerned, I think they’ll arrive at the same conclusion – no case. But I’m continuing in this case because I have a different worry; I think that even if nothing happens on the federal level, the Highland Park Police may pursue it on the state level, on the grounds of Texas theft statutes in regard to fraud. Henry Gardner has become personally involved in this case. When I first took the case, I realized the extent of the communication breakdown between Mrs. Christner and the Highland Park Police. I’m a resident of Highland Park and I’ve known Henry Gardner for a long time. I went to him as a friend and said I thought we’d better talk about the situation. Henry said, ’I know exactly what the facts are and I’d feel stupid discussing it.’ It was obvious to me he’d made up his mind. And that he’d gone out on a limb. He’s now in the ultimate position of saying the FBI is wrong. He’s got to see this thing through. And they may saw the limb off. At any rate, my concern stems from the fact that it’s kind of an old Texas custom that a district attorney’s office honor any Texas chief of police. If Chief Gardner should choose to file this case, it’s possible that one of Henry Wade’s assistant D.A.’s would bring authority in the case almost as a matter of courtesy. And, if they do, we’ll win. I like trying winners.”

Janiece Christner leans forward in the armchair in her living room and sips a cup of coffee. Dressed in a loose-fitting olive green blouse with puffy sleeves, black pants, and white house slippers, she sits in casual contrast to the stately elegance of the room around her. But the room has no air of stuffiness; it feels, in spite of its antique austerity, lived in.

She is not an attractive woman: short, bulky, with thin hair and a rough hewn face. When she frowns, her countenance is dark, slightly disturbing. But when she smiles, her face undergoes a dramatic change: Her dark eyes twinkle and her smile sends forth a warm radiance. She is an engaging and likable character. Her voice is gruff, hard-edged, but has an earthy, rural appeal. Her conversation is punctuated with mild profanities which somehow don’t stain the intelligent, artistic flavor of her discussion of soft paste porcelains. She is, all in all, not the kind of woman you would expect to find in the sophisticated confines of an art-bedecked Highland Park mansion. Yet, somehow, she does not seem out of place.