Anna was awakened by the sound of footsteps coming up the stairs. Groggy, she thought that perhaps one of her roommates had come back to school early. She looked up and saw a figure in the doorway of her bedroom. As she struggled to shake off sleep, the figure walked over to the side of her bed: It was a thin young man, holding a knife. “Don’t scream or I’ll kill you,” he said.

“I won’t scream. Just put the knife down.” He didn’t move. “What do you want?”

“All I want is some ass.”

“You can do anything you want, as long as you put the knife down.” He put the knife on the pillow behind her head. Couldn’t he take it downstairs? No.

By this time, Anna had gotten a good look at her attacker. She was somewhat nearsighted, and had taken her glasses off when she lay down to sleep. But in the dim light, his basic appearance was clear: a dark young man of medium height, unusually thin. He wore denim jeans and jacket and a ski cap. His hair fell halfway to his shoulders. His accent was Spanish.

The man began to remove his pants. He ordered Anna to undress. When she had trouble unhooking her bra, he offered to cut it off with the knife. His pants and underwear off, he ordered her to perform fellatio, but after five or ten seconds he withdrew.

When she realized that she was in danger, Anna’s first thought had been that she must keep talking to him. “Was the door unlocked?” she asked.

“Yes. Do you live here by yourself?”

“No, I have two roommates.”

“Where are they?”

“Home for Christmas vacation. I came back early.”

“I just needed a woman so badly.”

“I can understand that.”

Still wearing his denim jacket, he got into bed with her. She felt the light contact of his penis – he was starting to enter her. She tried to relax, to minimize the pain. But he stopped. “I can’t do this,” he said. “I’m sorry. I’ve never done this before. I apologize.” He got out of her bed and started to dress.

My God, he’s changed his mind, he’s going to leave, Anna thought. She lay very still.

“Why was your phone off the hook?”

“I was tired. I didn’t want to talk to anyone. I can’t see very well,” she added. “I’m nearsighted, and without my glasses I can’t see very well at all.”

“That’s good, I guess,” he said, picking up the knife and walking toward the bedroom door. He stopped in the doorway. “I’m sorry to have bothered you,” he said.

Anna heard him walk downstairs. There was silence for a few moments; she feared he would come upstairs again. Then she heard the back door close.

Anna looked out the bedroom window which overlooked the back of her apartmen complex. The attacker walked along the back of the building, turned left, and moved out of sight. She looked at the clock: It was 2 a.m. The whole incident had lasted about 10 minutes.

Shaken, Anna lay back down. Why had this happened? Had she really left the door unlocked? She didn’t think so. But she had only lain down to nap; she had expected to wake up again and work before going to bed for the night. So maybe she had left it unlocked. Why hadn’t she awakened earlier? If she’d been up, working, with the lights on, maybe none of this would have happened. The thoughts ran around and around in her head.

About 20 minutes later, she got out of bed, dressed, and left the apartment. A good friend lived across the street; she could stay with him. When he answered the door, she started to explain, but it was too much. Her friend never really understood what was going on, but yes, of course, she could sleep on his couch. He stumbled back to bed and she was alone again.

She was nervous, shaking inside, but exhausted as well, and relieved. No physical harm had come to her. What it all boiled down to was a few seconds of oral sex and the knife; it was the knife that really scared her. Here, with her friend one room away and the door latched, she was safe. The attacker couldn’t find her. She would call the police in the morning. She finally fell asleep, and didn’t wake until noon.

If he hadn’t stolen her purse, she might never have called the police. It had been on the dining room table downstairs when she had gone up to bed; when she returned home a little after noon the next day, it was gone. Gone, along with all her identification, photographs of her family, and a diamond ring, a family heirloom her mother had given her for Christmas. So that’s what he’d been doing in the moments before she heard the back door shut: The sorry son of a bitch had stolen her purse.

The police were furious. Nearly 12 hours had passed since the attack; if she had reported it immediately, her attacker might have been picked up near her apartment, with evidence linking him to the crime. Now that was impossible.

Contrite, angry about the theft, Anna gave the police a description of her assailant, the attack, the contents of her purse. Neither Anna nor the police considered the crime a rape.

Anna Malloy Jackson*, 28, was the oldest daughter of Irene Malloy and Henry Adams Jackson of Calder, Iowa. It was Anna’s natural intelligence and her father’s good fortune in the sale of some very fertile farmland that had broken her loose from the strict Christian training of her childhood, and brought her to a doctoral program in education at UT/Dallas. “I seem to have a good deal of natural ability, and school has always been easy for me,” she says, without conceit. Since high school, her ability had carried her through a succession of degrees at progressively better colleges. At the Dallas school, she was one of the top graduate students in her department; she was known especially for her work with children with reading disabilities.

Her friends teased her about her constant struggle against laziness and disorganization; they chided her for being indecisive at times, and too ready to accept full blame for everything that went wrong around her. But Anna was a kind, gentle person with quiet integrity, and she had the affection and respect of almost everyone who knew her.

It was the struggle against laziness that brought Anna back to her Dallas apartment from her parents’ retirement home in Phoenix the day after Christmas, 1976, several days before her two roommates were expected to return. “I had prelims coming up in March, and I was feeling guilty about how little I’d studied for them, so I came back early. I’d been at my desk for three days, seeing almost no one. But the night of the rape I was having trouble concentrating for some reason. I’d gone up to bed early, about nine o’clock, and started to read a novel. I’d turned off all the lights downstairs – we were trying to save money on our power bill – but I really meant to come back down later and work. After reading a while, I felt tired and decided to shut off the light and sleep for a while. I’d even taken the phone off the hook.”

The rapist had awakened her about five hours later.

As the victim of a violent sexual crime, Anna didn’t seem typical. But an investigator familiar with her case said, “The only typical reaction among rape victims is that they feel invaded, violated to some degree. And they feel guilty if they think they could have done something to prevent the attack. But Anna’s a good gal, she’s nice people. She was at home in bed minding her own business and in no way brought on the attack.”

Still, Anna felt some guilt: “If I’d only been up working with the lights on, maybe the whole thing never would have happened. But I never felt any guilt over the rape itself.

“That was just something that happened.”

Anna watched the student health center nurse, a friendly young woman named Billie, prepare the lab slide. This was a very accurate test, Billie explained, placing a drop of Anna’s urine sample on the slide and then, next to it, a drop of clear liquid. She began to mix the droplets together with a stir stick. If the mixture turned cloudy, the result would be positive; if it remained clear, negative. Anna watched as the solution turned milky. Billie, still cheerful, looked up from the slide. “You’re pregnant.”

It wasn’t a complete surprise. She had missed a period in January, but it would have been her first after going off the pill in late December, so missing it was not worrisome; some women wait six months or a year for normal ovulation to begin again. There had been other symptoms: fatigue so marked that she had felt like going back to bed at noon, just four hours after rising – perhaps she had mononucleosis. Her breasts were unusually swollen and tender. Then, in February, she had missed her second period, and the thought of pregnancy crossed her mind.

The test left little room for doubt. A slide agglutination test for urinary HCG (human chorionic gonadotropin), it detected the presence of a hormone that the developing placenta began to produce about 10 days after fertilization; HCG is, among other things, an apparent cause of the nausea associated with the early stages of pregnancy. The slide test was, as Billie said, fairly accurate: Some pregnancies might escape detection early on, but there were almost no false positives.

It had to be David. They were friends, TAs under the same professor, and one night – as much because of the hours they spent working together as anything else – they slept together. That was late November, when Anna was on the pill, so it had seemed safe. But at the end of her pill cycle, there had been two pills left over. It had to be David.

But it wasn’t David – not according to Dr. Adams, director of the student health center, who gave Anna a pelvic and abdominal exam right after the slide test. “How far along do you think you are?” asked Dr. Adams. Anna had slept with David in the last week of November, which would make her about 15 weeks. No, that was not likely at all. Dr. Adams didn’t know exactly how far along Anna was, but it was almost certainly not 15 weeks; she’d detected uterine enlargement more compatible with 10 or 11 weeks. Was there another time Anna could have become pregnant? Well yes, there had been the rape – the attempted rape, with no real penetration and no sign of ejaculation. But that was the only other time; calculating forward from the rape, Anna was 11 weeks pregnant. Impossible, but there it was.

“She was very concerned to know exactly how far along she was,” Dr. Adams says. “It seemed that if her friend were the father, she wanted to keep it, and if not, she wanted to get rid of it.”

Anna remembers, “I hoped it was my friend, because he’s a very talented guy, extremely bright.” When Dr. Adams asked Anna if she wanted to bear the rapist’s child, Anna replied, “No way.”

I told Anna that there was no way to be sure how far along she was,” says Dr. Adams. “That early in pregnancy, most physicians are not examining for any reason except to say whether or not the woman is pregnant. You just tell them, you’re two months, or you’re three months, or whatever – you give them a vague idea, and generally that’s all you have anyway. It’s the women who are considering abortion who really care how far along they are, who need a date – and that’s the only time you get down to weeks.”

With abortion a possibility, it was literally a matter of weeks – 12 weeks, the cut-off date for a relatively safe abortion. Neither Dr. Adams nor Anna was really satisfied with the 10-or-ll week guess; they needed a more reliable estimate. Dr. Adams scheduled a sonogram for Anna at St. Paul’s Hospital on March 10, 1977.

When asked why she sought additional evidence, Dr. Adams says, “In my experience, attempts to date pregnancy on the basis of physical examinations and the patient’s memory of possible times of conception are at best dubious. The results pretty much depend on how hard you push, where you push, and who does the examination.” She never appeared to doubt Anna’s claim that if she were 11 weeks pregnant, it could only be the result of an unsuccessful rape attempt. Admittedly, it strained one’s credulity: “The odds are very, very low. Most of the time you just don’t believe the person – you figure they’re denying the facts or lying. Inside, you just sort of chuckle. I believed Anna, though it struck me that it was a real phenomenon.”

Anna doubted the 11-week figure, too. The odds of getting pregnant as the result of what had occurred the night of her attack were too low to be believed. “Those were, to say the least, unusual circumstances of conception. I mean, I’ve heard of teenagers just petting and semen being on the outer organs of the female and becoming pregnant that way. But I had felt no actual penetration, nor had I any evidence of ejaculation. So I asked again and again, ’Could this really have happened?’ ’Couldn’t my friend possibly be the father?’ ” Dr. Adams obviously wasn’t sure. If she had been, she wouldn’t have ordered the sonogram.

Sonography, or medical sonar, is the use of high frequency sound waves for medical diagnosis. Like X-ray photography, it gives a picture of the body’s internal structures without surgery; unlike X-rays, sonography apparently has no harmful effects, even on a developing fetus. It has been used since the late Fifties to determine fetal age, and it is considered by many doctors to be one of the best indicators of how far advanced a pregnancy is. But its accuracy depends on the skill of the technician who performs it and of the physician who interprets it, as well as on the age of the fetus. Peak accuracy is attained between 14 and 24 weeks of pregnancy, when the margin of error is plus or minus two weeks.

Anna simply hoped the sonogram would support one of the two possible dates of conception. On March 10, when the test was performed, Anna knew that she was either 12 or 16 weeks pregnant.

The test results in Anna’s medical file at the student health center read: “Pelvic sonogram demonstrates slight enlargement of uterus and a well-formed gestational sac. Estimated fetal age would be six to eight weeks. No abnormalities are noted. . . .Conclusion: a six to eight week pregnancy.”

The report was vague at best, even for Dr. Adams. It listed both fetal age and the length of the pregnancy as six to eight weeks, which was impossible. Pregnancy is calculated from the first day of the last period, fetal age from the day of conception, and these normally differ by about two weeks. Was the report saying Anna had a six-to-eight-week-old fetus and an eight-to-ten-week-old pregnancy, or a four-to-six-week-old fetus and a six-to-eight-week-old pregnancy?

Dr. Adams doesn’t recall exactly how she evaluated the sonogram. “It was the best piece of evidence I had,” she says; more reliable, evidently, than Anna’s feeling that she must be either 12 or 16 weeks pregnant. If Dr. Adams recalls correctly, she told Anna that she was about eight or ten weeks pregnant.

Eight weeks, 10 weeks, 12 weeks – it didn’t really matter to Anna. A figure of 14 weeks or less meant the rapist was the father.

She knew, at any rate, who the rapist was. At the end of January 1977, before Anna suspected she was pregnant, she received a call from the police: They had a suspect. On January 23rd, they had arrested Frederick Wayne Sanchez, 22, on suspicion of the burglary of the residence of Katharine Harper, 30; in a crime similar to the one against Anna, a young Mexican-American assailant had entered Miss Harper’s apartment, terrorized her at knifepoint, and attempted to rape her. Four days after the arrest, acting on a tip from an informant, the police had found the knife used in the attack on Katharine Harper under a Coke machine at an apartment complex near both her residence and Sanchez’s. With the knife was a plastic insert from a billfold, containing photographs, identification, and the Texas driver’s license of Anna Malloy Jackson.

On the last day of January, Anna positively identified Sanchez from police photos as the man who had attacked her one month earlier.

Nearly everything Anna learned about her attacker came from the district attorney’s file: Frederick Wayne Sanchez, Mexican-American, born September 3, 1954, 5 feet 7 inches tall, 129 pounds. The file contained a record of arrests dating back to 1974: two arrests for possession of marijuana, one each for criminal trespass, assault, and vehicle theft. There was one conviction for possession of marijuana. A lawyer with the district attorney’s office described Sanchez’s early record as a simple history of “misdemeanor stupidity” – until the crimes against Katharine Harper and Anna. In the words of an investigator with the D.A.’s office, who was closely involved in the preparation of the case against Sanchez, he was simply “slime.” “What can you say about a guy like that? I have first offenders that I can try to help, but this wasn’t his first offense, wasn’t even his first violent crime. I had no feelings for him but contempt.”

This man, according to Dr. Adams and the St. Paul’s sonogram, was the father of the child Anna carried. She sought confirmation twice more in early March, once at the North Dallas Women’s Clinic in Richardson, once from a gynecologist in her town. Neither new estimate was anywhere near 16 weeks, which would have supported the hypothesis that her friend was the father.

“When Dr. Adams first told me the rapist was the father I believed she was right, but then I started reading, and she admitted it was sometimes difficult to tell. But then each time I would go to be examined, the doctors would say, ’Yes, she’s right,’ and I became more and more convinced that I didn’t know what I was talking about. I truly did believe the rapist was the father. I’d been to as many places to have myself examined as 1 could and everybody told me the same thing.”

It was time to have an abortion.

Anna had made an appointment for an abortion the day she discovered she was pregnant: Dr. Adams would perform a suction D and C at Reproductive Services Inc. in Dallas on March 12, two days after the sonogram. It was a safe, routine procedure, Dr. Adams felt: The cervix would be dilated, the fetus removed from the womb by suction, the womb checked with a curette to make sure that all structures associated with the pregnancy were removed. It could be performed any time during the first trimester.

By March 12, though, it was clear that it wasn’t going to be that simple. Anna had seen three doctors and sought counseling in the past week, and everyone she talked to had expressed, intentionally or not, an opinion about the abortion. Dr. Adams offered to perform the abortion, but then said, “It’s so ironic – I just had a miscarriage, and here you are.” “We just sat there,” Anna recalls. “I was sort of in a daze, but I remembered it.” There was Dr. Baker, a local gynecologist Anna visited in an attempt to check Dr. Adams’s estimate; he was adamantly opposed to abortion. Though he didn’t push, he reminded Anna that adoption was a possibility; his own children were adopted. There was Alice Newton, a social worker at Presbyterian Hospital: “She told me that couples would call up offering to build a church for the Presbyterian synod if they would only get them a child. She said the going rate for a baby on the black market in New York was $22,000. People wanted children so desperately, and here I was – I just didn’t want to take nine months out of my life.”

The only place where abortion had seemed entirely unproblematic was the North Dallas Women’s Clinic in Richardson, where Anna had gone to get another estimate of the date of conception. “It was a classy place, very affluent looking, and the girl who took me in and explained the abortion procedures was very beautiful, genteel-looking and very kind. I thought, ’Here’s this lovely girl doing this – it can’t be bad.’ As I sat waiting to see the doctor, I saw girls go in for abortions and come back out a short time later, as if nothing had happened. It looked so sim-pie.”

Taken together, the events of the past week didn’t amount to anything very definite, but Anna was being pulled in more directions than she’d expected.

The evening before her appointment at Reproductive Services, Anna sat in her living room, talking with one of her roommates. The March 14th issue of Time had just arrived, and Anna thumbed through it as she chatted with her friend. Marabel Morgan was on the cover; inside were features on “galloping inflation” and a farewell to “The Mary Tyler Moore Show.” And then, on page 61, a full page of color photographs of human embryos, photographed in the womb with a new optical technique. One picture showed an embryo with clearly formed eyes and fingers; it seemed to be sucking its thumb. It was eight weeks old; Anna’s was about ten weeks old.

The day of the abortion appointment, Anna arrived at Reproductive Services, Inc., 2339 Inwood Road, at about 10 a.m. She had had trouble finding the clinic; it was at the end of a dingy row of small businesses. She doesn’t remember seeing a sign anywhere; as she entered, she felt as if she were in a scene from a movie, where women sneaked into an anonymous doorway to have a dirty job done. But this was legal, of course.

“The decor was yellow, I remember, with a green rug and a TV set and some magazines. I stood at the front desk a long time, waiting for my name to be taken, and looked around the waiting room. There were all kinds of women – some very poor-looking. A lady at the clinic told me later that they used abortions as their method of birth control. There were some extremely young girls, with their parents, and some very chic-looking women sitting alone. There were a lot of guys in there too, most of whom looked extremely uncomfortable. The men were, to me, the most lost-looking ones there.

“I remember thinking, ’They’re all waiting to kill something.’ I kept thinking that. But then, I thought, ’Yeah, but Anna, that’s silly, that’s ridiculous. You didn’t ask for this pregnancy, you’ve got a career to pursue; what’s it going to do to your family? How’s the baby going to react to being the product of a rape?’ All these things … I just wanted to get through it, that’s all.

“I never talked with the other women. Everyone was in her own little world. We would talk to the people in charge, but not to each other.”

Anna checked in, gave a blood sample, and paid the $125 fee, cash only. Then she asked to use a phone. A girl led her to the back of the clinic where, for the first time, Anna called her mother in Phoenix.

“I told her I was pregnant, that it was the result of a rape, and that I was about to have an abortion. She was terribly upset. Not crying – my mother isn’t the kind to break down and sob – but it hit hard. My mother always leaves things up to me, but she said, ’Well, I’d advise you to get the abortion, because if it’s the result of a rape, I don’t see how you are responsible. Why should you have to go through this?’ She said that having a baby would take nine months out of my life, and if I had it, she didn’t see how I could ever give it up. She said, ’I couldn’t do it, and I don’t think you’ll be able to either.’

“And then she said she wished I hadn’t told her.”

The last of the clinic’s required preliminaries was a counseling session, Anna was led to a small room, “a little cubicle, like the places you’d try on clothes in a very cheap store, like a Gibson’s. A counselor came in and talked to me – I never knew her name, but I liked her. I told her everything, all the conflicts that were going through my mind.

“She was very calm, and used this logic: If the baby were in fact the result of a rape, then it was a mistake. An abortion, to right that mistake, was the same as nature’s righting a malformed child by miscarriage. It was taking care of flaws. This made sense to me.

“Then she said, ’Tell me, when you’re ready, what you’ve decided,’ and left me alone in that little room, with olive green shag carpet – I stared at it – a little mirror, and one magazine. It was awful.

“I knew I’d done all the preliminaries, so I’d be going right in for the abortion. I thought, ’Okay, Anna, all you have to do is get up and walk into that room and it will be all over and you can go home.’ I knew all I had to do was put one foot in front of the other and just walk. But I was immobilized. After trying three or four times to get up, I realized it was ridiculous. I called the lady back in. She said she didn’t think I was ready to do it, so to go home and think about it, that I had more time. She said I had a lot more time to think.”

Shortly after the March 12 appointment at Reproductive Services, Anna called her father. “I thought he was the one who could direct me, guide me; and since I couldn’t seem to come to a decision on my own, I went to him. That was one of the hardest things I did in my life.

“I told him the whole thing. I told him about the rape, that I was pregnant by the rape, and that I was having difficulties deciding what to do and wanted his opinion on the matter. He asked me, ’Are you sure it was a rape?’ I told him I thought it could have been the November time, but that the doctors told me no.

“He just spoke in a monotone: Yes, all right, we’ll think about it and call you back. I could tell from the tone in his voice that he was fighting inside.

“Mother told me later what happened when he hung up. He was furious. He went into a tremendous rage. He felt somehow that I had done this to him. ’She’s just trying to get back at me,’ he said. He didn’t believe me about the rape – he thought I’d just gotten pregnant someplace and didn’t want to admit it. He said, ’I don’t want to have anything to do with her, I just wash my hands of her.’ To Mother he said this, but never to me.

“But he called me back the next day to tell me what he had decided: I should not have the abortion, I should have the child. My father even offered to keep the child in his home and raise it, which is, for him, amazing. He said to keep my chin up, if I needed anything to let him know, and that they would be coming up to see me.”

None of it helped very much. Anna’s mother felt she should have an abortion; her father opposed it; she had caused hem both grief and was no nearer to a de-:ision than before.

Anna’s medical records, on file at Reproductive Services, show that after her March 12 visit, she made appointments for March 15th, 16th, 18th, and 19th; there is no record that she showed up for any of them. But she did return to Reproductive Services once more in late March.

The last visit was made largely at the insistence of Laura, a close girlhood friend she had rediscovered in Dallas recently. “I’d gone over it all with Laura,” Anna says, “and she just couldn’t see me having the baby. She said, ’All right, Anna, this is ridiculous. You just can’t have a child at this point in your life. I thought I was pregnant right after my second baby and we were going to have the child aborted, so why do you feel you have to go through with it?’ So I said, ’Okay, Laura, I’ll try again.’ “

Laura drove her to the clinic. “We walked in and stood at the desk while they checked me in. I was so detached – I remember feeling like none of this had anything to do with me. I stood there and watched everyone in the room, and finally I said, ’I just can’t do it. There’s just no way.’ “

That might have been the end of it. Anna wishes it had been – that her vacillation, procrastination, backing out represented a decision. “I wish I could say that I said, ’Nope, no abortion,’ but in fact, I never did that. I went through incredible indecision, and 1 thought about it constantly.” For Anna, as long as abortion was possible, it was an issue.

In the end, the decision was made for her. In early April, Anna went to the Fair-mount Clinic in Dallas to check out, again, the possibility of having an abortion. Based on the dates given her by Dr. Adams, the St. Paul’s sonogram, the North Dallas Women’s Clinic, and Dr. Baker, she should have been between 12 and 15 weeks pregnant – too late, perhaps, for the first-trimester abortions performed at Reproductive Services, but well within the 17-week limit the Fairmount placed on its dilation and extraction method.

A doctor at the Fairmount performed a routine pelvic and abdominal exam, and concluded that Anna was not 12 to 15 weeks pregnant, but 19 weeks – an estimate that placed the time of conception squarely between her single intercourse with David and the attempted rape. This was the first medical indication that her friend might be the father.

At 19 weeks, however, abortion was not really an option any longer. She was only one week short of the deadline for a legal abortion of any kind and too far along for anything but an induction abortion. In this grisly procedure, a strong saline solution, prostaglandin, or urea is injected into the uterus, where it kills the fetus and induces labor; within a day or so, the child is born dead. If the fetus weighs more than 20 grams, the law requires a burial.

“I was so horrified at the thought – not of the pain, but of lying there, knowing that I would go into labor and deliver a dead baby. I don’t think I could have done it.” Few physicians would have advised her to: Induction is no safer for the mother than bearing the child after a full-term pregnancy.

“I remember feeling a real sense of closure about the whole issue at the Fair-mount, like ’This is it, it’s too late.’ Which was bad. I hate that – that for once in my life I didn’t just say . . . but I didn’t.”

Shortly after the Fairmount exam, Anna went to one of her regular meetings with Mr. Fleming, her graduate advisor and director of her dissertation research. They hadn’t gotten a lot of work done that semester – mostly they talked about Anna’s pregnancy. “He just could not see me having this baby – he didn’t see why I would want to have it. He thought that it was, in some way, a perverse punishment I was inflicting on myself – that happened with several of my friends. After the Fairmount I remember being not quite honest with Mr. Fleming. I told him it was too late, and in my mind, it was.”

On April 19th, a final attempt was made to determine how advanced Anna’s pregnancy was. It was done at the request of a couple who had expressed an interest in adopting her baby; they wanted to know its race. “I enjoyed that sonogram. I remember feeling very good that day. The nurses were very nice and we laughed and joked – they had to hit my stomach to get the baby in place.” Ten images of the baby’s head were taken in an attempt to measure its biparietal diameter (the widest diameter of the head, just above the ears). Given the biparietal diameter, gestational age could be read from a standardized chart. The measurement was 47 millimeters; this correlated with 19 weeks from the first day of the last menstrual period. If Anna had been counting the weeks carefully, she would have noticed that it looked like the parents would be getting a Mexican-American baby after all. But, “I no longer cared. The basic decision had been made. Now, all I had to do were the practical things.”

Another case was coming to a close. On April 6th, Frederick Wayne Sanchez had pled guilty before a jury to charges of burglary of the habitation of Katharine Harper with the intent to commit rape. Sanchez was sentenced to 10 years’ probation on April 10th. The prosecutors were unsatisfied with the sentence – “If we don’t get penitentiary time for an offense like that, we don’t feel we’ve done our job,” said one spokesman – and continued to pursue Sanchez for the crime against Anna Jackson.

Though her presence was not required, Anna went to the county courthouse on the day of Sanchez’s trial. She didn’t enter the courtroom, but from the hall she saw him for the first time since the attack four and a half months earlier. He was pitiful. “They had cut his hair short, and dressed him in a dark suit and white shirt, obviously brand new. He looked thin and scared.” He never noticed her, and she never saw him again.

On May 16th, 1977, Frederick Wayne Sanchez pled guilty to aggravated sexual abuse of Anna Malloy Jackson. He was sentenced to 10 years in the state penitentiary at Huntsville.

Anna had asked an apparently simple question of six medical experts: How far advanced is my pregnancy? Four answers placed the time of conception two to four weeks after the rape; one places it about a week before the rape and three weeks after she slept with David; the sixth, squarely between the two. No doctor had claimed better than a two-week margin of error, nor was she sure what all their terms meant: gesta-tional age, fetal age, weeks LNMP, so many weeks pregnant, a uterus that looked like so many weeks. To her mind, none of this was definite enough to rule out the possibility that her friend was the father; after the Fairmount exam, she came to believe that he was, in spite of what the doctors said.

“I wanted the father to be David – I felt the child would have been very talented, very intelligent. And I didn’t know anything about this idiot, nothing at all. I felt it would have been harder for the child to know it was the result of a rape than of two friends going to bed together.

“I don’t remember anyone saying a harsh, mean word to me about the preg- nancy, except for my father – and even he was unusually supportive – but I had a sense of closing myself off, doing my own thing, and getting my life regulated and not taking charity from anybody.

“As it turned out, with other people 1 , was exonerated by having been the Victim of a rape.’ With my family, 1 thought, Okay, if I hang onto the fact that it was really my doing and it turns out to be the rape, so much the better. But if it goes the other way – if I hang onto the rape and it turns out to be my friend – then 1 look stupid, I feel stupid, and I have all this mental adjustment to make. So I think I ’ was protecting myself – assuming the worst, taking on guilt for having been irresponsible with the pill, just in case.”

During Anna’s first visit, on July 6, Dr. Wyeth performed a standard abdominal exam, to estimate how far into the abdomen the uterus had expanded. He wrote “umbilicus plus three” on her chart – the top of the uterus was three finger tice. Dr. Wyeth saw her nine times in the weeks before the birth-more frequently than the average patient, because, “Seeing her so late in her pregnancy, 1 hoped to determine how far along she was by following her more closely than usual. And I thought she needed support.”

During Anna’s first visit, on July 6, Dr. Wyeth performed a standard abdominal exam, to estimate how far into the abdomen the uterus had expanded. He wrote “umbilicus plus three” on her chart – the top of the uterus was three finger breadths above her navel. On the basis of this examination and the result of the April 19 Parkland sonogram, Dr. Wyeth concluded that Anna was 29 weeks pregnant. This finding placed conception precisely on the date of the rape.

Anna and Dr. Wyeth argued about paternity until she delivered. “I did everything but say, ’Look, Anna, this is not your friend’s baby,’ ” Dr. Wyeth recalls. “That question was at the center of every discussion we had. She’d ask, ’But couldn’t my friend be the father?’ It seemed that if it were her friend’s baby, she might keep it and raise it.

“I was afraid there was something deeply emotional going on that I didn’t understand. I didn’t want to shatter her defenses, if that’s what they were-let’s face it, it was a trauma either way. She’s just so nice, you want everything to go well for her.”

All in all, things were going pretty well for Anna. After school ended, she began working through a variety of temporary employment agencies as a typist, for $3.50 an hour; that, plus the remains of her salary as a teaching assistant, was paying the medical bills. She had taken two short-term loans from friends to pay for the last sonogram, but not one penny had come from her parents. In a burst of physical fitness that became something of a legend in her own mind and her friends’, she joined Weight Watchers and started riding a one-speed bicycle to work every day in the height of summer, sometimes as far as 15 miles round trip. Her friend Laura sewed maternity clothes for her. Incredibly, almost no one at work said anything about her pregnancy. “It was not at all like I thought it would be- ’You’re not married? You’re pregnant? You can’t work here.’-I had visions of that, but it wasn’t that way. I don’t know if I could have gotten through it fifteen years ago, but everything conspired in my favor-people’s attitudes, styles in clothing, everything.”

Once, with guilty but genuine pleasure, she made the pregnancy work to her own advantage. “One afternoon I had to tutor a little boy, and 1 hadn’t yet bought his books, so after work I rode my bike over to the bookstore. I got there right after the clerk had locked the door. He was sorry, but he wouldn’t let me in. It was really hot – one of those 102 or 103-de-gree days – and I was just desperate. So I turned sideways and pulled my dress tight in the front a little and in two seconds he walked over and unlocked the door.”

If David were the father, the delivery date would be August 21. On the 18th Dr. Wyeth performed a pelvic exam and found much greater cervical dilation than he had anticipated. He still didn’t think her friend was the father, he said, but judging by the physical signs, the baby could arrive any time.

And then, nothing. The August due date passed, then three more weeks, ,and nothing happened. Anna quit work on September 1; she had little to do but sit around the house and wait.

On September 21 at 10:45 a.m., Anna checked into the hospital. Dr. Wyeth had decided to induce labor. The first contractions came at about 11:30. They were nothing much – Anna had thought it would hurt more. She had no bad pain until about 2 p.m.; for the next four hours the contractions were very difficult to bear. At six, Dr. Wyeth gave her an epidural anesthetic, a “luxury” in his words: It left her alert and in no pain, and did not drug the baby. The nine hours of labor that remained were, Anna recalls, like a party. Eight friends and her mother stayed with her in the labor room; they all got a little giddy as the hours passed. Early in the morning of September 22, she went into hard labor – still no pain, but terrible effort and concentration.

As the baby’s head emerged, Dr. Wyeth told Anna he thought he should administer a general anesthetic. “1 told her it was best that she be asleep, so that she didn’t see the birth, hear the baby cry, or see it. 1 asked her if that was okay with her, and she said all right.”

On September 22, at 3:35 a.m., unconscious from a shot of sodium pentathol, Anna gave birth to a baby boy, seven pounds, three ounces’. The baby was perfectly formed. Judging by its overall coloration, its fine head of silky black hair, and the dark brown tissue of its scrotum, Dr. Wyeth concluded that it was of Mexican descent. When asked how certain he was, he shrugs. “One hundred percent. You could tell by looking.” The birth took place 266 days, one hour and 35 minutes after the rape: a textbook case.

Anna remembers that when she awoke in the recovery room, still foggy from the sodium pentathol, she reached for Dr. Wyeth’s hand and kissed it. “Is everything okay?” she asked, and then, “Was it the rape?” Very definitely. She felt great. At 10 a.m. she got up, took a bath, and washed her hair. Her room at the hospital was like the Hilton, the food wonderful, the nurses very kind. She kept taking codeine and feeling terrific.

On September 24, Anna signed the adoption papers. With them, she enclosed a letter she had written to the adoptive mother, who was coming for the baby later that day.

“It sounds very syrupy, maybe, but it wasn’t. To me, it was very real. I just wanted her to explain to the child, when he was old enough to understand, that I had not given him up because I didn’t care about him and his future. I had done what I thought was best for him and me. I wanted her to make that very clear to him, I wanted him to know I wasn’t deserting him. It wasn’t a very long letter. I think she might keep it. It is something I would keep.

“The main thing, though, was whether to see the child. 1 wanted it all to close, to finish in my mind. Dr. Wyeth felt it was better that I not see the baby, but I chose to see it.

“It was like when someone dies, and you have to go in and see them. When I got off the elevator, I was afraid I had made a mistake, but I had them wheel me over to the window. My mother was on my left and my friend Laura was on my right – I had on a blue dress, I remember – the nurse showed me which one he was. The baby was over in the corner, with no name – they had written “Baby Jackson” on his crib. He was asleep. Mother said, ’Anna, he doesn’t look a thing like you.’ And he really didn’t. He was very dark. So I cried, I just sat there crying, and I knew I had sealed it by seeing the baby. Otherwise I would always have wondered. Then we got in the car and came on home.”

On September 26, two days later, Anna Jackson celebrated her 29th birthday.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

Finding The Church: New Documentary Dives Into the Longstanding Lizard Lounge Goth Night

The Church is more than a weekly event, it is a gathering place that attracts attendees from across the globe. A new documentary, premiering this week at DIFF, makes its case.

By Danny Gallagher

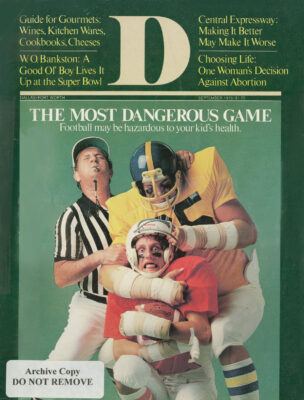

Football

The Cowboys Picked a Good Time to Get Back to Shrewd Moves

Day 1 of the NFL Draft contained three decisions that push Dallas forward for the first time all offseason.