Darryl picked up his pencil, stared absent-mindedly at the World History text on the desk before him, and methodically drew an arrow through Archduke Ferdinand’s head. Sixth period, Friday afternoon. What a drag. There was old Mrs. Wilkerson droning on about Serbian nationalism while outside, the late February afternoon was sunny, almost warm. Darryl fidgeted in his chair and checked the time; he sighed. Just another quarter of an hour, and another day of time served at Miller Junior High School*, Richardson, Texas, would be behind him.

Darryl surveyed the classroom. Nobody ever paid any attention in this class. Casey, directly across the aisle, was, of course, dead asleep. Casey was the best classroom sleeper Darryl had ever seen. He just propped his right elbow on the desk, laid his forehead on his right hand with his fingers spread through his California blonde hair, set his left hand and forearm on the desk for support, and passed out. With a book open on the desk, it looked like he was reading. Darryl had never seen this precarious pose collapse. The only time Casey ever got in trouble was when he snored, but he was only too happy to take the risk. “Only two good reasons to come to school,” Casey once told Darryl, “To catch up on your sleep, and to get drugs.”

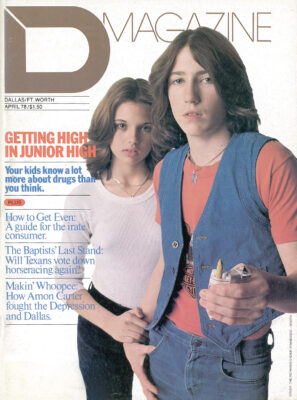

Casey wasn’t the only one in Mrs. Wilkerson’s class who felt that way about drugs. In fact, even for a ninth grade class, this one had more than its share of freaks. There were only two important status groups at Miller Junior High, as far as Darryl was concerned: the “freaks” and the “socials.” The distinction was clear to everyone – probably was at every other junior high in Richardson, or anywhere else, for that matter. The socials were the cheerleaders, and jocks and all the other doers. The freaks, well, the freaks were doers too – they did drugs. There were, of course, crossovers, the so-called “frocials” – freaks who dabbled in the social scene, socials who dabbled in drugs. The rest of the students, the middle mass – the straights, the bookworms, the Dilberts – didn’t really count for much.

There wasn’t any open animosity between the two cliques, but they went their separate ways. It wasn’t as if the freaks didn’t like to party – they definitely did; and it wasn’t as if the socials were immune to drugs – a lot of them smoked dope every now and then. But the attitudes were different. The socials were still into school spirit and all that; the freaks were only into getting high.

Generally, they coexisted pretty well, except for occasional flare-ups, like that little episode last November. Mary Beth, one of the super-socials, had gotten it into her head to lead a self-appointed committee of three into the vice principal’s office to lodge a complaint about pot smoking on the football team. They’d even cited two players as being at the root of the problem. The two were later called into the counselor’s office where, of course, they denied everything. (Darryl, however, was sure it was true; he knew of several jocks who smoked pot. He also knew for a fact that Barry, on the track team, took speed sometimes. He was fast as hell, too.) Anyway, word of the incident whipped through the school; there weren’t many big secrets at Miller. And nobody had been too happy about it. Mary Beth, of course, denied that she was the one who had narked, but everyone knew. Darryl figured Mary Beth probably wished she’d never done it.

Darryl ran his fingers through his dark silky hair and swept it behind his ears. He caught Brenda looking at him from the other side of the room. Lissa had told him that Brenda was still after him. “Brenda says you’re the fourth best-looking guy at Miller,” Lissa had told him. Darryl couldn’t deny being flattered; Brenda mostly hung around with dudes from the high school. Lately it was Danny. Dealer Danny. Yeah, Brenda was a weird one. She looked more like a social, but she was definitely a freak.

People like Brenda made it hard to figure what the percentages were: Darryl figured at least 50 percent of the people at Miller had smoked pot. At least half. And that was because a lot of seventh graders weren’t into it yet (though some of them started in elementary school). In the ninth grade, the percentage, by his own calculations, was definitely higher. 75 percent? Possibly. He also figured that of that original 50 percent, maybe half were into other drugs besides pot. Maybe more, maybe less. It was hard to say. One thing for sure, though, there were a lot of people into a lot of drugs. And that’s who most of Darryl’s friends were. Or had been. Still were, he liked to think. He wasn’t sure what he was now. There wasn’t really a category for ex-freaks.

Jeff: “Pot is just a hobby.”

Jeff took another hit off his cigarette and glared at the foos-ball table in front of him. On the other side of the table, Casey was grinning widely. “Four to one,” Casey taunted. “You’ve had it, man.” On any other night, Jeff would have one-upped Casey’s teasing. But tonight, he couldn’t get his head into the game. Danny was supposed to have shown over an hour ago, and there was still no sign of him. He wasn’t really all that wild about this place anyway – too many condescending high school people in here – and two hours of waiting hadn’t helped his patience. But Danny had said he wanted to meet at Starrs, and since Danny had the dope, Jeff was here at Starrs.

Jeff scratched distractedly at the sparse black stubble on his 14-year-old chin and cued up the ball for another game. Hunkering low over the bright-green foosball table, he attacked the ball with a vengeance, trapping it on the near side. A brief pause, and he flicked his wrist, firing the ball past Casey’s frantic goalie and into the goal pocket with a loud wooden smack. Jeff sighed with satisfaction, as he stepped back from the table and retrieved his cigarette from the ashtray. So milch for games. Here came Danny.

Jeff didn’t know Danny too well. He knew he was a year or two older and he knew that he provided Casey with most of his dope. That was enough. Danny shuffled up, hands stuffed in his jacket pockets, dirty-blonde hair bouncing at his shoulders. “Well, what’s the story?” demanded Casey. “You got it?”

Danny grinned. “In the car.”

“Good,” said Jeff, more relieved than excited. Danny gestured toward the parking lot and led the pair outside.

Starrs was located on the corner of a shopping center development in a still rather barren outskirt of Richardson. The three climbed into Danny’s car, a dented yellow Plymouth Duster.

“Any pigs around here tonight?”asked Danny.

“There were a couple when we first got here,” said Casey. “A couple hours ago. But not since then. They didn’t hassle anybody.”

“We’ll just stay here then.” Danny turned the ignition key and pushed a Ted Nugent tape into his tape deck. The music pounded through the speakers, fuzzing slightly from past liberties taken with the volume knob. Danny reached under his seat and pulled out a rumpled brown paper sack. “You just wanted one lid, right?”

“Yeah, he did,” said Jeff.

“I’ve got two if you want both of them.”

“No, man, I don’t have enough bread for both.”

“Okay. It’s excellent pot, though. Definitely better than average commercial. Oaxacan.”

Yeah, sure, thought Jeff. The usual line. Jeff inspected the baggie handed to him. Looked okay. Fairly clean, a few stems. And good-sized. He opened the bag and gave it a cursory sniff. Good enough. “Yeah, this is cool. Uh, how ’bout the Quays? Casey, you asked about the Quaaludes, didn’t you?”

“Yeah,” said Danny, “but I couldn’t get ’em tonight, man. The dude’s car broke down in Garland, so I won’t see him until tomorrow.”

Jeff slumped back in the seat. Damn, he thought. The Quays were the whole point. He’d been really psyched for downers and now nothing. Except pot. “Well, okay, man,” Jeff said. “Maybe tomorrow.”

He reached into his pocket and pulled out two crumpled fives and handed them to Danny; Danny handed him the plastic baggie, which Jeff licked and sealed and stuffed into the front of his pants. Danny swung the car out of the parking lot and they roared off into Richardson. He changed tracks on the tape deck, turned it up and lit a joint. Jeff, in the back seat, stared out the window as they sped down Spring Valley Road. Pot, Jeff mused. Pot really isn’t a high. Pot’s just a hobby.

When Jeff and his family moved to Richardson from San Diego several years earlier, he had been crushed. Nine years old at the time, he had been looking forward to a big summer with all his friends. Then his Dad had dropped the bombshell – they were moving to Texas. Jeff knew nothing about Dallas, but learned soon enough there were no beaches and knew instantly he would hate his new home.

His parents bought a three-bedroom house in a booming Richardson subdivision. Jeff and his older brother Stuart, who was 12, were miserable. During that first summer, they talked about running away, going back to San Diego, but mostly they just watched TV and played around in the vacant lots near their house. Jeff and Stuart were in the field one day, making life difficult for a large anthill, when Garry and another kid came over to them. Garry lived down the street and was a little older, 14, but Stuart had talked to him a few times. The other kid looked even older.

“Hey,” said Garry, without introduction, “y’all wanna get high?”

Jeff and Stuart exchanged confused glances. “What?” Stuart finally mumbled.

“C’mon,” said Garry, leading them out of the field.

In the alley behind his house, Garry pulled a misshapen cigarette from his T-shirt pocket. Jeff knew then what was going on. He’d heard of marijuana, heard his parents talk about it. But he’d never thought about it much and he’d certainly never tried it.

Garry explained to Stuart how to suck in smoke and air at the same time and hold it in his lungs as long as possible; Jeff watched with fascination as Stuart took his first awkward toke. “Let him try it,” said Garry, motioning toward Jeff. Jeff took the joint between his fingers and felt his insides pounding. He didn’t know if he was scared or thrilled, but not for an instant did he consider backing down. After all, Stuart had done it. Jeff sucked at the joint and held his breath and waited. Nothing happened. When he could hold his breath no longer, he exhaled loudly and waited. Nothing.

He watched the joint go around and tried again, not sure that he was really getting any smoke at all. Garry and his friends giggled at him, imitating the way he puffed his cheeks out as he held his breath. Jeff laughed with them, but tried to keep his cheeks in when he took his third toke. Still nothing. When the joint had burned down to a small nub, Garry extinguished it against the fence post and put the remainder back in his pocket. “The roach is the best part,” he explained authoritatively. “All the resin. I’m gonna save it for later.” Big deal.

The next day Garry brought three joints. They smoked them in succession. This time, Jeff got stoned. He remembered laughing hysterically when Garry and Stuart set fire to a small bush in the field and Garry tried to stamp it out in his tennis shoes. Jeff watched the flames pop and sparkle and spit as Garry stomped gleefully and howled with mock screams. Jeff loved it. It was the most fun he’d had since he’d left San Diego.

Garry turned them on to some other stuff that summer. First it was Arrid Extra Dry. “It’s like flying,” Garry said as he sprayed some on a rag, held the rag over his nose, and breathed deeply. Jeff tried it. It wasn’t his idea of flying, but it was a fine giddy rush through his head. It faded away in less than a minute. “You have to keep doing it to stay high,” Garry advised. Jeff was doing a can a day by the end of the summer, but then all the stories hit about how it rotted your brain cells, so Jeff quit.

Sometimes they’d go over to the track where another friend of Garry’s raced his go-cart. There was usually an open washtub of gasoline and they’d put their heads over the tub and breathe the vapor. It was a quick head rush, but not much of a high. Once Garry brought some Mare-zine, motion sickness pills he’d bought at the drugstore. Jeff took five, as Garry prescribed, but they made him feel hyper, nervous. So he never did those again. The thing he liked best was pot.

And he still liked pot, Jeff thought as he sat on the floor of his bedroom long after Danny had dropped him off. Pot was like water. Everyday, anytime. Jeff didn’t spend much time with other people and pot was easy to do by yourself. Pot was something to do by yourself, Jeff thought. At least it kept his life from being total boredom.

He inspected the bowl of one of his pipes, from which he was carefully scraping the resin with the small blade of a pocket knife. There was some pretty good blackish resin build-up in this bowl. He’d get enough here for a few good hits for tomorrow night. Not that it would blow him away or anything, but if those Quays didn’t turn up. he’d decided he wanted to have something on hand besides plain old reefers. This “homemade hash” just might have to suffice. Anyway, scraping the pipe was something to do. He didn’t feel like going to sleep yet.

Jeff turned over the Kansas album on his stereo, keeping the volume low since his parents were asleep across the hall, and sat back down on the floor with his pipes. His gaze fell proudly on the three marijuana plants growing in his window. More than growing, they were positively glowing under the Gro-lux lights he’d rigged above them. Those plants were his passion at the moment. He’d already picked a place out in Piano where he would transplant them when it got warm. He figured if he kept it secret and nobody ripped them off, they’d be beautiful by September. He’d grown them from seeds from the best pot he’d had all year and figured if they stayed healthy, he might harvest enough to last him through next winter. Or he could sell it off in lids and make a bundle. He smiled fondly at the plants, particularly at Mean Joe Green, the big one in the middle, and thought about how envious his friends were that he could grow dope in his own bedroom. Jeff’s parents had always been pretty cool about pot.

His parents never said how they knew, they just knew. Jeff still wasn’t sure how they first found out. He assumed that his mother had discovered his brother’s stash. When Jeff and Stuart had gotten home from school one afternoon, their mother had sat them down at the kitchen table and calmly said, “Your father and I know that you two have been smoking marijuana. We’re not happy about it and it’s not something we can condone because it is illegal. But we know we can’t stop you if it’s something you want to do. So, if you insist on continuing, we want you to smoke it in your bedroom where it’s safe. But only in your bedroom. Not outside where you could get caught. Is that understood?” Jeff and Stuart, in shock, could only nod their heads. Jeff remembered thinking that it sounded like his mother had rehearsed her speech all day. Jeff didn’t know anybody else whose parents knew, much less said okay. Jeff and Stuart talked about it that night and Stuart said their parents were probably thinking that if they took all the secrecy out of it, the fun would be over and they’d stop smoking. Their parents obviously didn’t know how much fun it was to get high. Jeff just figured he was lucky because his parents were from California so they were more liberal.

The bedroom smoking arrangement had worked fine until last year. Two things blew it. First, Jeff was busted. Well, almost. He had been riding in a car when the cops pulled them over and found two lids – which happened to be under the front passenger seat, where Jeff was sitting. They weren’t his lids and Jeff had finally gotten out of the bust because it wasn’t his car; but the whole thing had really made his dad mad. Then, only two weeks later, his parents were entertaining a couple from out of town. The man was a business associate of his father’s. Jeff had come home from a smoking session over at the park, and his dad had called him into the living room to meet the guests. Jeff stuffed the rest of his lid in his jacket pocket; and when Jeff pulled his hand out to shake the man’s hand, as he’d always been told to do, the plastic bag somehow caught on the ring on his little finger and fell out of his pocket. Jeff could still remember the sickening plop of the baggie hitting the floor and the embarrassed silence that followed. There was little Jeff could do but pick up the bag, stuff it back in his pocket, mumble his excuses and head for his bedroom.

When the guests left, his father came storming in, screaming. No more pot in the house. Period. Jeff still couldn’t believe his lousy luck. And now, as he sat admiring his plants, he couldn’t believe his dad had let him keep growing them in the house. When his dad had first discovered that they were marijuana plants, he’d told Jeff to throw them out. But Jeff had pleaded, saying that if he grew his own he wouldn’t have to buy any; buying, he lied to his father, was risky, the surest way to get busted. The subject had never come up again.

Now, as he placed the crumbly bits of resin in a small piece of aluminum foil, folded the edges, and placed it carefully in his wooden stash box, he realized he felt no real guilt for hassling his parents. Pot was his life; they’d have to understand. Jeff flipped off the stereo, removed his jeans and climbed into bed. Tomorrow was Friday. Thank God. Hope those Quays come through.

Deanna: “Wild Turkey is the king.”

She woke up slowly to the blaring of her clock radio at her bedside. As usual, she didn’t remember setting the alarm, though she knew she had; she was getting pretty good at that. What was today? Friday. Good. She considered skipping school, but since she’d skipped on Monday, she decided she’d better get up and go. She heard the front door of the apartment slam shut and knew that her mother had left for work. She slid her legs over the side of the bed, stroked her straight dark hair out of her face, cupped her hands around her forehead, and contemplated the state of her head. Not bad. A little fog, but no pounding. As usual, though, Deanna was thirsty.

She reached under the bed and pulled out the quart of Wild Turkey, still about a third full. She unscrewed the cap, took two quick shots from the bottle, screwed the cap back on, and headed for the bathroom. Wild Turkey, she thought. It is the king.

The bathroom mirror was never particularly flattering to Deanna in the morning. But she didn’t look too wasted today. She looked older than 14, but she’d always looked older than her age. She knew she wasn’t beautiful, but she wasn’t bad looking either. And except for that little ring of flab around her waist, her body was nicely developed. Nice enough, she said to herself. Nice enough not to have any trouble with guys, anyway.

When she’d dressed, Deanna found her purse and pulled out the empty perfume bottle, which she expertly filled with Wild Turkey from the quart. She put the quart back under the bed, carefully placed the perfume bottle back in her purse, and went to the living room. Her younger sister, Carla, a fifth grader, was in the kitchen finishing a piece of toast. They ignored each other as Deanna went to the sliding glass door that opened out onto the tiny enclosed back patio. Outside, she picked up a can of Budweiser from the concrete step she’d left it on the night before. The can was still chilled from the cold night air. Deanna had become fond of this little ritual over the course of the winter. As she returned inside with the beer, she caught Carla’s disdainful stare. Deanna glared back. ’”You eat your toast, I’ll drink my beer,” she said spitefully, holding the can out in Carla’s direction and popping the top. “Little bitch,” she muttered, and headed out the front door.

Walking to school, sipping the Bud-weiser, Deanna thought about her father. He was after her again to come live at his place. Since the divorce two years ago, he’d tried to persuade Deanna to move back with him several times. At least I wouldn’t have any trouble getting Wild Turkey, Deanna thought. Wild Turkey was her father’s drink, too. Must be hereditary.

Things weren’t any better with her mother. Ever since last summer, when Deanna had gotten them kicked out of their old apartment, her mother had been silent and hostile. At least they’d been yelling at each other before. The apartment thing had really finished it. Deanna had somehow convinced the manager, Mrs. Kirby, to let her have a small party at the complex’s poolside clubhouse. No booze, Deanna promised, knowing that Mrs. Kirby had never liked or trusted her anyway. Word got around though, like it always did. All the high school guys that Deanna had been messing with showed up, and a lot of people she’d never seen. Of course, there was booze. And pot. And pills. Deanna had tried to keep things under control for a while. It took a lot to get her drunk, but she kept drinking steadily and by 11 o’clock was pretty well loaded. That’s when someone handed her four phenobarbitols which, for no real reason, she’d dropped into her cup of beer. She remembered that the beer was warm and the phenobarbs turned it green. Somebody told her not to drink it, which was all the encouragement she needed. She remembered little after that.

But when Deanna woke up the next morning on the living room couch – God knows how she got there – her mother was standing at the front door listening to Mrs. Kirby, whose voice was stern. The clubhouse had been thoroughly trashed – windows were broken, the pool table had been ruined, debris was everywhere.

She had no choice, Mrs. Kirby said, but to evict them from the apartment complex. “I feel sorry for you,” Mrs. Kirby said to Deanna’s mother, “having a daughter like her.” That still hurt. But it had been one hell of a wild party.

Deanna arrived at the Wall five minutes before the first bell for school. Actually, it wasn’t a wall, just a small alleyway about a block from Miller Junior High, bounded on both sides by fences and a few trees. And it wasn’t very secluded, particularly for smoking pot, which is what Deanna and the other freaks did here most every morning. In fact, most of the regulars at the Wall were pretty sure the teachers had viewed their morn-ing convocations. But the teachers never said anything about it.

Deanna’s friend Lissa was already here, already stoned. Lissa whooped as Deanna lobbed her empty beer can into a rash barrel 20 feet away. “Go ahead and finish it off,” Lissa said, offering Deanna a half-smoked joint. As Deanna inhaled, she examined the morning gathering: A typical crowd, she thought. The regulars, a few part-timers, all here for the same reason she was: to get ripped before school.

Darryl: “For a cheap high. Liquid Paper or allergy pills.’’

Darryl started smoking dope in seventh grade. He and his friend Gregg got a ride to a Z Z Top concert with Gregg’s older brother and a few other people. A couple of joints were lit and passed around in the car. It was all very natural, no fanfare, nobody even said anything about it. In fact, they were talking about the game the Cowboys had lost that afternoon. He felt no pressure to participate, and he could have easily passed it up. But he’d been aware of pot for a while and had always figured that when the opportunity arose, he’d try it.

He didn’t get high that time, but eventually he did. And he liked it, more than he expected to. Darryl’s popularity had always rested on his reputation as a clown, a comedian, and pot seemed to loosen up his act even more. He wasn’t sure if he got funnier or if everybody was just more ready to laugh, but it was great.

Since pot had proved a successful experiment, Darryl experimented more. Over the past two years, he’d tried most everything. The cheap highs. He’d bought Locker Room at head shops, $5 for a small glass vial that lasted a long time. He’d inhale it in class and get that amazing butyl-nitrate body rush. It always bothered him that it made his heart beat so fast, but he figured it couldn’t be top bad since it was legal. How did they get away with selling it as a room deodorizer?

Liquid Paper was another cheapie for sniffing in class; last year they were selling Liquid Paper and Liquid Paper Thinner in the school supply store until officials finally got wise. It had been a hot-selling item. He’d tried No-Doz a few times too, when people gave it to him in school, but it mostly just pitted out his stomach.

The cheapest high of all had been his allergy pills. He was supposed to take one or two a day, but he found if he ate five or six at a time, he could get a nice numbness. And his mother never questioned it when the prescription had to be refilled. How could she not notice they were disappearing so fast? She must have thought of them as medicine; if the doctor prescribed them, they couldn’t be bad, right?

Darryl had been into some heavier drugs as well. Last summer he’d done a lot of psychedelics, mostly mescaline. Tripping had been incredible, sometimes more than just getting high: There were stunning revelations and mental connections, he thought. Impossible to describe and impossible to put together again after he came down. Psylocibin was nice, too. Danny and Casey had driven out to East Texas last summer and picked psylocibin mushrooms (the good ones, the right ones, they’d told him, grew out of cow patties). They’d brought back a plastic bag full, chopped them up, mixed them with raspberry Kool-Aid, and had a party out at Lake Dallas.

But tripping seemed to get less and less interesting. Or maybe he’d just gotten scared of psychedelics. By the end of the summer, he wasn’t doing them much anymore.

There had been some drugs Darryl just hadn’t liked from the start. Speed, for one. Speed was great for about two hours, a drag for the next six. A lot of kids sure liked it, though. Partly because it was so easy to get. Danny’d once told him how easy it was to crack a scrip: Just find a willing fat chick, get her an appointment with the doctor (Danny knew the names of several good diet pill doctors), get a prescription, and have it filled. Danny paid for the doctor’s examination and gave the girl some speed for her trouble: Benzedrine, Black Mollies – Mollies were the big favorite. Danny used the same routine to get Valium; he just used willing nervous-can’t-sleep chicks instead. And he had no trouble selling Valium. It was mild and nice. An easy classroom drug.

Heavier downers, Darryl thought, were okay in small doses, if you just wanted to get serene. But basically, he didn’t trust them; he’d seen too many people get dangerous on downers. And he’d never really gotten into heavy drinking. He wasn’t sure why, really. Maybe just because getting drunk took so much effort.

Darryl had snorted coke a few times – he wasn’t about to pass that up when everybody said, “Cocaine’s the best, man, it’s the best.” He’d figured it was about $5 for every 25 minutes of bliss and that was too much for an unemployed ninth grader. Heroin was one drug Darryl had never gotten close to. Like most people he knew, he was afraid of the needle. They’d all seen the film in school with the guy’s arm turning green; most of those drug films were a bunch of propaganda, sure, but shooting up was still scary. He knew of only a few people who’d used a needle, and they were shooting speed. As far as he knew, nobody at Miller was hitting up heroin. But then, he hadn’t really been into the drug scene for a couple of months.

Over the past Christmas vacation a succession of events had changed Darryl’s attitude toward drugs. The first was a party held in a big, ranch-style house. By the time he arrived everybody was getting pretty loaded. There were pot and booze everywhere, and obviously assorted other chemicals available. Most of the people were older, high school age, but Darryl spotted a few freaks from Miller too.

The strangest thing was that right in the middle of the den, sitting on a big couch, was a woman at least 35 years old. She was watching television, oblivious to the chaos around her, except that she would occasionally look up and gaze around bemusedly at the party. She was drinking a cocktail. He didn’t see her talking to anyone; she just sat there.

“Who is that?” Darryl finally asked Alan, a guy he’d bought pot from.

“It’s Julie’s old lady,” said Alan.

“Who’s Julie?”

“This is Julie’s house, man.”

“What’s she doing here?”

“Who? ’

“Julie’s mother.”

“Well, she lives here,” said Alan, laughing.

“Yeah, but . . . why’s she just sitting there, y’know?”

“Oh, don’t worry about her, man. She’s cool as hell. You can do anything you want. The only rule is to stay out of the master bedroom. All the other beds are open house.”

“You’re kidding.”

“No, man. Check it out. Really, she’s a crazy lady. Cheryl told me she’s a lawyer. Far out, huh? There’ve been a couple parties here before and there’s never been any hassle. Tonight she even made marijuana brownies.”

“Is Julie’s old man here too?”

“Nah, they’re divorced. She got the house.”

Darryl tried not to be disturbed by her presence, but he was. Then he noticed at the other end of the long couch a boy who couldn’t have been more than five years old. He was smoking a reefer. A few older kids were gathered around him, laughing as the little kid would dial the operator, scream a few obscenities into the phone, and hang up, giggling hysterically. He was obviously Julie’s little brother. His mother was still watching television. Weird.

Later that night, Darryl bought another lid from Alan. Alan always claimed his pot was “dusted” with something. The last time it was “dusted with cocaine.” Not likely, thought Darryl. Nobody would waste good coke on pot. This latest purchase was supposedly “dusted with THC.” Darryl didn’t sample it until the next afternoon. It tasted fine, but it gave him the worst headache he’d ever had. Later that night he tried again, and the resulting headache was even worse. The pain was almost unbearable. Darryl was as mad as he’d ever been. More than anything, he hated getting ripped off.

To complicate the holidays further, Darryl’s parents were hassling him more and more. He’d always gotten along fine with his parents; basically they’d trusted him and gave him free rein. But during the last year they’d become increasingly suspicious of him. They tried to be discreet, but it was painfully obvious. Darryl had always hated the deception of drugs; he’d considered laying it all out in the open for his parents, but knew it would be disastrous. They’d be horrified.

Then, on the night before New Year’s Eve, Darryl had done some acid with some friends and returned home about 3 a.m. The house was dark and quiet and Darryl was still tripping. Though coming down, he was nowhere near sleep. He wandered into the den, turned on the television, and slumped into a chair. Next to the chair on a table was a nearly empty bag of nacho-flavored Doritos. Mindlessly, he began munching on the chips as he stared at the TV screen. He was only vaguely aware that the station had long since signed off, and the screen now showed only a flurry of electronic snow. Darryl had become absorbed in what he was seeing as “flea races,” tiny individual colored dots that moved gradually from left to right across the screen. He became mesmerized by one particular “flea,” which did not move; it only jiggled as the other fleas went racing by. “That flea is me,” Darryl’s mind began telling him. “Going nowhere. Just sitting here. Wasted. That flea is me.” There was no sadness. But through the haze Darryl felt the wellings of a sudden, profound, and inexplicable depression.

“What’s the matter with you?” His father’s voice suddenly burst through the room. Darryl’s head snapped around to see his father, in a bathrobe, standing in the doorway. He had no idea how long his father might have been watching him. “What?” Darryl mumbled, momentarily frightened, confused.

“Are you on drugs, Darryl? Are you on marijuana?” His father marched into the room and suddenly thrust his hand in front of Darryl’s mouth, held it there for a moment, and then sniffed it. He was smelling for smoke, Darryl realized, for marijuana. But he was smelling only nacho-flavored Doritos. For one flashing instant, Darryl’s whole life seemed overwhelmingly ludicrous.

Over the next two days, Darryl had come to the gradual realization – not a decision really – that he was going to stop doing drugs. He wasn’t sure why. Perhaps just to see what it was like without them again.

Cheryl: “She’d always been good at not getting caught.”

The cafeteria was throbbing by the time Cheryl and Deanna arrived. They were always about ten minutes late because they stopped for their daily pre-lunch rendezvous in the girls’ bathroom. There, Deanna drank her Wild Turkey; Cheryl was less picky. As often as not, she didn’t carry any with her; she could always get a hit from Deanna or somebody else if she wanted it. Deanna always had hers.

Cheryl had been drinking since she could remember; ever since her father put her on his knee and gave her sips of beer, which she had loved from the first taste. But a few shots of whiskey at lunch was no big thrill. She knew that Deanna didn’t really do it to get high, either. It took a lot more booze than that for Deanna to get a good buzz. She could outdrink most guys. Deanna drank at school because she got thirsty.

Cheryl would have preferred a noon joint, actually, but smoking pot at lunch was a hassle. The bathrooms were too risky because of the smoke and the smell; cigarettes were tricky enough. And it was too much trouble to try to slip out of school, get high, and slip back in. People did it. but it was a nuisance. It would be nice to get into high school, Cheryl thought; her sister had told her you could just walk outside at lunch and toke up. Anyway, nothing wrong with a little swig of Wild Turkey for lunch, since she never ate anything in the cafeteria anyway. Her mother gave her $ 1.50 for lunch money, so that added up to an easy $7.50 a week.

Cheryl and Deanna sat down at the usual table with the usual freaks.

’”You wanna go shopping this afternoon, Cheryl?” Deanna asked.

“Sorry, I don’t shop.” said Cheryl.

“Me either.”

“Good. Let’s go shopping then.”

They both laughed; they’d been “shopping” together before. Both were accomplished shoplifters. Clothes, records, anything. For Cheryl, it was as much for the satisfaction of doing it as for the merchandise itself. Once they’d ripped off a bunch of 45’s from a record store. The records were old “classics” they’d never heard of, and they never listened to 45’s anyway; but it had been a challenge to see how many they could get. When they got outside and counted up their loot, they had 23 records between them. That was an odd number, and they couldn’t divide them up evenly; so Cheryl went back and ripped off one more.

Something for nothing, Cheryl thought, as the cafeteria chatter and clatter cre-scendoed around her. That, she supposed, was really her whole trip. She’d always been good at not getting caught, from the time she started stealing from her parents’ liquor cabinet and adding water to the bottles to get the liquor back to the original level. They’d never noticed. And the summer she and Mark stole golf clubs off apartment patios and out of garages and sold them at pawn shops. That had been a breeze. And then there was the Friday cash supply. Cheryl knew that her mother went to the bank every Friday and came home with twenties in her purse. By ripping off only one $20 bill every other week, she’d never been caught.

In fact, the only time Cheryl had been caught stealing was a fluke. She’d helped Mark rip off a CB radio from Pain’s sister’s car. Pam found out somehow, and since she hated Cheryl anyway, Pam went to Cheryl’s mother and told her not only about the radio but about all of Cheryl’s drug life. Her parents flipped out and came down on her really hard. They actually wrote out a list of rules for her. Home by 8. No phone calls after 9. Had to stay downstairs and could not go to her bedroom until her parents went to bed. No more spending the night with friends. No makeup. Then they actually took away her bikini and bought her a one-piece.

For a week, Cheryl had tried to patch things up. There were lectures from her father every night. She couldn’t take it. On Friday she didn’t go home. She got drunk with Deanna. When she finally staggered home, her father was waiting. He was raving mad, screaming, lecturing. That was it, Cheryl decided suddenly. Still drunk, she stalked into her mother’s bathroom. Her mother, she knew, had been taking tranquilizers and she knew they were in her medicine cabinet. Cheryl poured out a handful of pills, gobbled them down, went to her bedroom, and prepared to die.

When she woke the next morning, she was confused. And hung over. She was lying on her bed with her clothes on. She pieced things together and remembered, vaguely, the medicine cabinet, the pills. God, what a fool, she thought. But what happened? Shouldn’t she be dead or in a hospital or something? She stumbled into the bathroom and opened the cabi- ? net, wondering for a moment if it had all been a dream. No, there was the pill bottle. Vitamins. Ever since, she’d wondered if even her drunken mind had known they were vitamins all along.

Darryl watched Casey doze off and wished he could do the same. This had been a long Friday. He used to like Fridays, but his weekends hadn’t been all that thrilling lately. He’d been staying home mostly, watching TV. Last weekend he’d played about a hundred games of backgammon with his little sister. It was strange, he thought. When you stop doing drugs, what do you do?

In fact, Darryl thought, just what the hell was he doing? His self-imposed straight life hadn’t proved anything. He already knew there wasn’t any instant status in getting high like there used to be. Now it was so common it was just a matter of whether you did or didn’t. So he hadn’t really been cut off by his friends or anything. But he definitely didn’t see them nearly as much. It was too hard to be around drugs and ignore them. Let’s face it, he said to himself. Drugs are fun. Usually, at least. And he missed them. Yeah, he definitely missed getting high. When you got right down to it, his life had been pretty damn dull lately.

Mrs. Wilkerson was into her steady drone, still wandering on about the Balkan power struggle. That’s another thing, Darryl thought. Drugs were interesting. Or could be. Some of those mescaline trips had been a hell of a lot more interesting than this ridiculous history class. After all, what was the sense in leaving your mind alone?

Well, who knows. He wasn’t even 15 yet. How should he know? Maybe drugs were okay. Maybe you could take drugs all your life and not get screwed up if you were smart enough. Deanna said her oldest brother smoked pot and he had a great job with some big company in Houston making a lot of money. Deanna said he even did cocaine sometimes.

But Darryl wanted to think about it some more. He wanted to try to stay straight and think about it. Because drugs were so … absorbing. It was so easy to pay all your attention to getting high. Maybe that’s what he was doing, Darryl thought, trying not to blow himself away before he figured out what the hell was going on. Of course, he’d probably never figure out what the hell was going on, so then what was he doing? Who knows. Maybe he’d start doing drugs again. Jeff had said he would.Lissa had said he would. Casey had saidhe didn’t even believe that Darryl hadstopped, that it was just one of his stunts.

For the time being, though, he’d decided, he was off everything. He stillsmoked cigarettes, but just for something to do. Nothing else. No pills, nopot, no booze even. His father had offered him a beer the other night and he’dpassed. He’d even stopped taking his allergy pills. What was really weird aboutthat was that his allergies had disappeared. Amazing, Darryl thought. Notthat it meant anything.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

Finding The Church: New Documentary Dives Into the Longstanding Lizard Lounge Goth Night

The Church is more than a weekly event, it is a gathering place that attracts attendees from across the globe. A new documentary, premiering this week at DIFF, makes its case.

By Danny Gallagher

Football

The Cowboys Picked a Good Time to Get Back to Shrewd Moves

Day 1 of the NFL Draft contained three decisions that push Dallas forward for the first time all offseason.