“I expect samples of hair found on the bed will be introduced,” he told the judge, “and I damn sure got a right to see if anybody had been in that bed.’’ Gossett denied the motion without batting an eye. Tessmer began to get the drift of things to come.

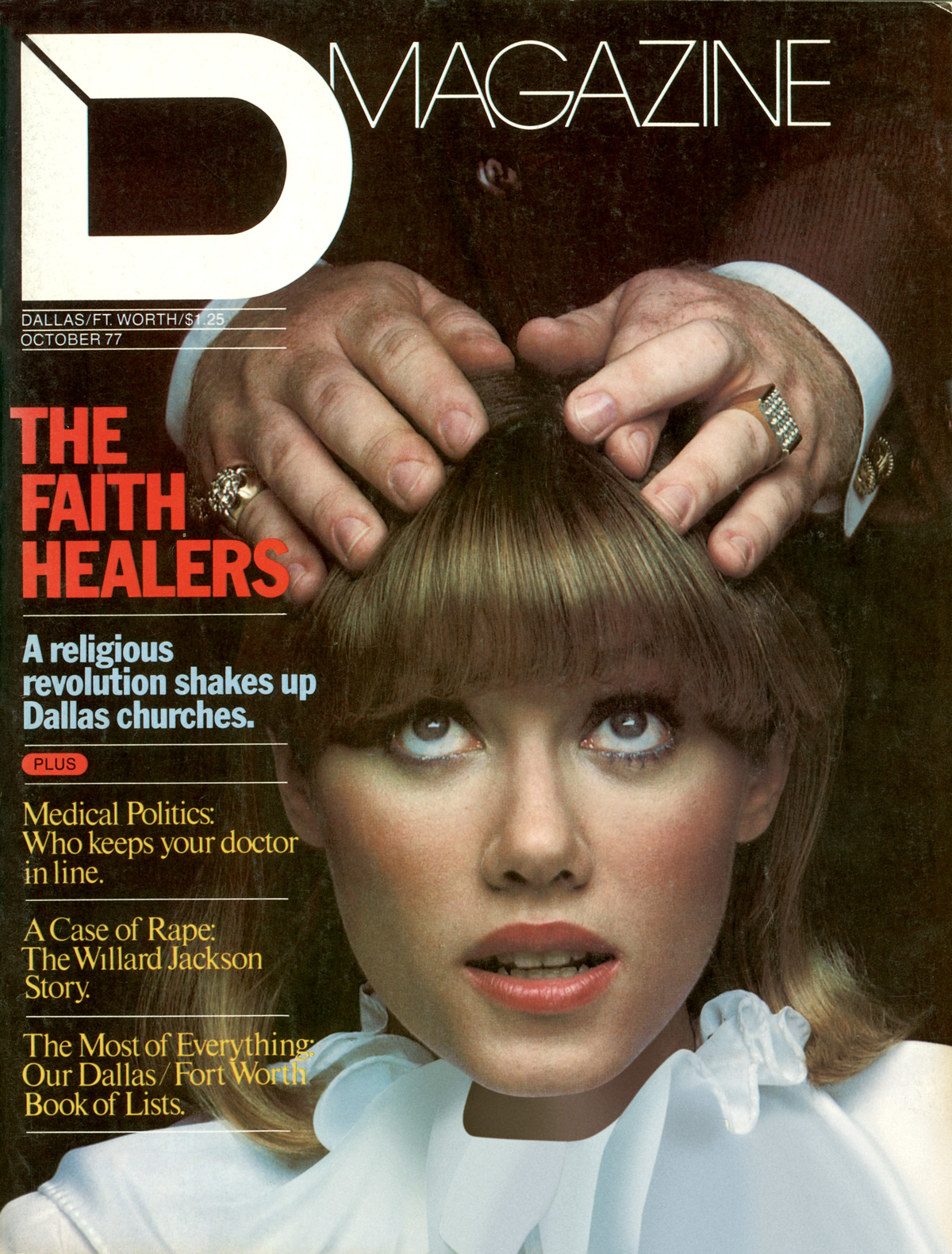

When the preparatory arguments were concluded, Les Eubanks introduced the case for the State. His first witness was Beverly Michaels. Dressed and coiffed conservatively, she took the stand confidently. Without hesitation, she recounted the gruesome events of the evening of November 28, 1971. Listening to her unwavering voice, Tessmer grew worried again. This was one smooth cookie, he thought. Victim identification may be all the State had, but they damned sure had the best ID witness he’d ever seen.

Beverly said she had returned home November 28 at about 11 from a date in Denton. When she unlocked the door to her second-story apartment, she discovered Margaret had latched the interior chain lock. She called to Margaret, who apparently had retired to her bedroom. Finally, her roommate came to the door, unlocked the chain and returned to bed. Then, Beverly said, she heard a voice behind her.

A nice-looking, well-dressed black wanted to know where a particular apartment was. Beverly replied that since she’d lived at the Americana only a couple of weeks, she didn’t know the apartment sequencing. Then he asked where the Blue Chip Club was. Beverly pointed to a small brick structure within view of her apartment. Then she testified, “He appeared to disappear.”

Beverly had gone into her apartment and dumped her purse on the coffee table. When she returned to close the door, the stranger reappeared. This time he wanted to know if he could use her phone. Beverly replied that no, she didn’t do that sort of thing, but if he would give her the number, she would place the call for him. He repeated the number to her three times, she recalled. It was either 745-8231 or 8213. Then she shut the door — without locking it — and went to the hallway to make the call.

“See,” the rapist said, “you girls didn’t have anything to worry about.” Then he shot them.

Under questioning from Eubanks, Beverly said she didn’t feel any mistrust for the man because the breezeway was well-lit, and she’d had a good look at him. He was well-dressed and well-spoken, she said: polite, almost apologetic. His speech, she continued “…did not have any accent. It was very clear, plain and distinct. His grammar, the using of the English language was very good. There was no accent in it that if you turned around you would not know that it was a black person that was talking.”

Beverly said she’d dialed the first three digits of the number when she heard the front door open and the unmistakable padding of footsteps in the hallway. She turned to find the stranger right behind her. He was pulling on black leather gloves, wielding a pistol. “This gun is cocked,” he said. “I will use it if you don’t cooperate.” He then asked her who else was in the apartment: she told him about Margaret. “Let’s go back and tell your roommate I’m here,” he said.

Beverly led the stranger back to Margaret’s bedroom and told her, “Margaret, we have a visitor.” The intruder then said, “Tell her what’s fixing to happen.” “I don’t know what’s fixing to happen,” Beverly replied. “I want your money,” he said. He’d then herded the girls to Beverly’s purse in the living room, brandishing the pistol to prod them on. Beverly dumped the contents of her purse on the floor and dug out about $50 for him. Then the three returned to the bedroom, where Margaret gave two or three dollars from her purse.

At this point, Beverly continued, he instructed them to strip. Margaret had started to unbutton her red housecoat, but the intruder interrupted, saying, “No, not you. Her.” Beverly then disrobed. At one point while she was taking off her clothes, the intruder said angrily, “Hurry up, I want a little pussy.” He instructed Beverly to sit down on the corner of the bed, with her buttocks as close to the edge as possible. He opened his pants and pulled out his erect penis; he entered her and thrust three times. Withdrawing his member, he instructed Beverly to “Finish it.” He then forced Beverly at gunpoint to take him in her mouth until he reached a climax. He ordered her to swallow it.

After taking Beverly’s watch, he ordered Margaret to strip. Both girls were instructed to lie on their backs on the bed. The intruder, now wearing a malevolent grin, sauntered over to the doorway, pointed the pistol at the floor and clicked the trigger twice. “See,” he said. “You girls didn’t have anything to worry about.”

Then he shot both of them.

Fighting back the blood now pouring into her throat, Beverly listened to the intruder leave. Then she heard Margaret stir, and turned to find her reaching for the phone. “Oh, Margaret, please don’t do that,” she cried.

And then he was back. Beverly heard him say, “Oh, I see we are trying to be a smart bitch.” She closed her eyes, expecting death.

“If you will just please yank the phone out of the wall, leave, we won’t do anything, we’ll just lay here, if you will just please leave,” Beverly screamed. The assailant left the room, and Beverly heard him fiddle with some phone wires in the living room. Just as quickly, he returned to the room, bent over Margaret and “did something to her.” Then he was gone.

The courtroom air now thick and still, Beverly continued her horrifying tale. She told of calling the police, her parents, her boyfriend on another phone in her room. She told of trying to give Margaret mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, even though it caused her to choke on her own blood. She told of the police arriving, giving a quick description of the assailant to a young patrolman, of being whisked off to the hospital in a daze.

Eubanks then directed her to the evening of January 15, 1972, the night she identified her assailant at the Sportspage. She told of seeing the man enter the club, dressed in a gray suit and black shirt; of watching him walk past her, barely 3 feet away; of his looking back at her two or three times as he mounted the stairs to the upper level.

The rest was perfunctory. Eubanks quickly and efficiently moved Beverly through the lineup that evening, her positive ID of Willard Jackson as the man who raped and shot her. When asked if that same man was in the courtroom today, Beverly firmly nodded and identified Willard Bishop Jackson, now seated impassively to the left of Tessmer, as the same man.

Charles Tessmer had some deciding to do, and he had to do it quickly. Beverly’s testimony had been about as devastating as an eyewitness victim’s can be: Concise, calm, firm, she was eminently believable. This was not a witness to get cute with on cross-examination. Clearly, the jury’s sympathy was now with her. Any attempts by the defense to impeach her testimony, to suggest she wasn’t telling the truth could only do more harm than good. This was generally the case in rapes, but it was particularly so with Beverly Michaels. Tessmer decided to handle the cross-examination with kid gloves, to proceed with caution and discretion.

Except for one big gamble he knew he had to take.

Tessmer started his cross by explaining that the defense wasn’t there to question that the crimes she described did in fact take place. They were merely here to prove that Willard Bishop Jackson did not commit them. Tessmer had a couple of areas to tidy up before his big move. He produced the black gloves and .22 caliber gun taken from Jackson’s home and asked Beverly if it were possible these weren’t the same items employed by the assailant November 28. Beverly replied that yes, it was possible they weren’t the same ones. He asked about the Sportspage the night of January 15, eliciting an admission that the place was crowded, and that there were only half a dozen or so other blacks there that night. Tessmer’s notion was to suggest to the jury that Beverly Michaels’ positive identification of Willard Jackson had been made under less than ideal circumstances: in a dark, crowded bar, for one thing; for another, out of a crowd of whites, not blacks. He pounded the point home more clearly with his next question. Do you have any particular expertise in telling one black person from another? he asked. No, not really, she replied, except that she’d gone to school with them.

Satisfied that he’d gone as far as he could with the point, Tessmer turned to the matter of the mustache. “Did the man that came in, the intruder, have a mustache?”

“I don’t remember,” Beverly replied. Tessmer took a quick look at the jury to emphasize the point. A knowing glance at the jury, a look that says, “Did you get that? That’s important” could sometimes be worth a thousand words.

Tessmer wasted no time bringing out another apparent discrepancy. “You said the defendant looked back at you two or three times that night at the Sportspage, isn’t that right, Ms. Michaels?”

“Yes,” she said, “that’s correct.”

“And after this man had looked at you two or three times he stayed in the place and did not try to leave, that’s true, isn’t it?”

“Yes, it is.” Tessmer let the implicit conclusion lie. If the jury didn’t add it up for itself, there was little more he could do to drive it home.

Now he was ready for his big play. Prior to trial, he’d notified jailers he wanted John Lee Lewis sequestered in a holdover tank for possible call to trial. Now he would bring the criminal into court, ostensibly to ask Beverly if she had ever been shown pictures of this man during the investigation, and if she thought he resembled Willard Jackson. His real notion, though, was to let the jury have a look at Lewis. It was an iffy ploy at best: For one thing, it smacked of cheap courtroom theatrics; no telling how a jury might react to that. Secondly, knowing Lewis as he did, there was just no telling what the guy might do. The memory of Beverly’s testimony that the intruder had been well-spoken and well-mannered was still fresh in the minds of the 12 jurors. If Lewis came loping in, looking goofy and crazed — which he was fully capable of doing — it would blow the point entirely.

John Lee Lewis, dressed in tattered white denim prisoner’s garb, was ushered into the courtroom, amid murmuring from the packed gallery. Tessmer pivoted the criminal around and around in front of Beverly before asking her if she recognized the man. No, she said, she’d never seen him before. Had she been shown any pictures of him while in the hospital? Not that she remembered. Well, then, would she agree that this man did resemble the defendant, Willard Bishop Jackson?

Yes, she would agree with that, she said.

Tessmer glanced back at the jury. No telling what they were thinking. The admission from Beverly that Lewis and Jackson did, in fact, look somewhat alike was significant. But the experienced lawyer could not tell whether the jury bought the point or not. Maybe they did, but maybe they were simply thinking, “Well, so what?” Still, though Lewis had hardly been the perfect model of a well-spoken, well-mannered black, he hadn’t come off as a wild-eyed lunatic. Tessmer was reasonably satisfied his ploy had worked.

Then it happened. As bailiffs prepared to usher Lewis from the courtroom, the prisoner turned to the judge and blurted, “Could I ask a question, whether or not—’’

“No you may not,” interrupted Judge Gossett angrily.

Eubanks and Tokoly leaned back in self-satisfaction. Tessmer groaned inwardly. Damned if Lewis didn’t go and blow it all to smithereens by popping off in open court. Worse, he’d elicited an angry rebuff from the judge. Juries took that sort of thing seriously. Tessmer said he had no further questions for Beverly.

Author